My Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Like many bloggers and other book addicts, I’m irresistibly drawn to the new books released each year. However, I consistently find that many memorable reads were published earlier. A few of these are from 2022 or 2023 and most of the rest are post-2000; the oldest is from 1910. These 14 selections (alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order), together with my Best of 2024 post coming up on Tuesday, make up about the top 10% of my year’s reading. Repeated themes included adolescence, parenting (especially motherhood) and trauma. The two not pictured below were read electronically.

Fiction

Fun facts:

- I read 4 of these for book club (Forster, Mandel, Munro and Obreht)

- 3 (Mandel, McEwan and Obreht) were rereads

- I read 2 as part of my Carol Shields Prize shadowing (Foote and Zhang)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Nonfiction

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

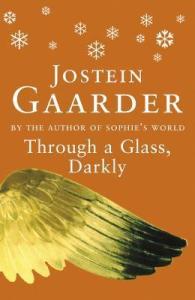

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

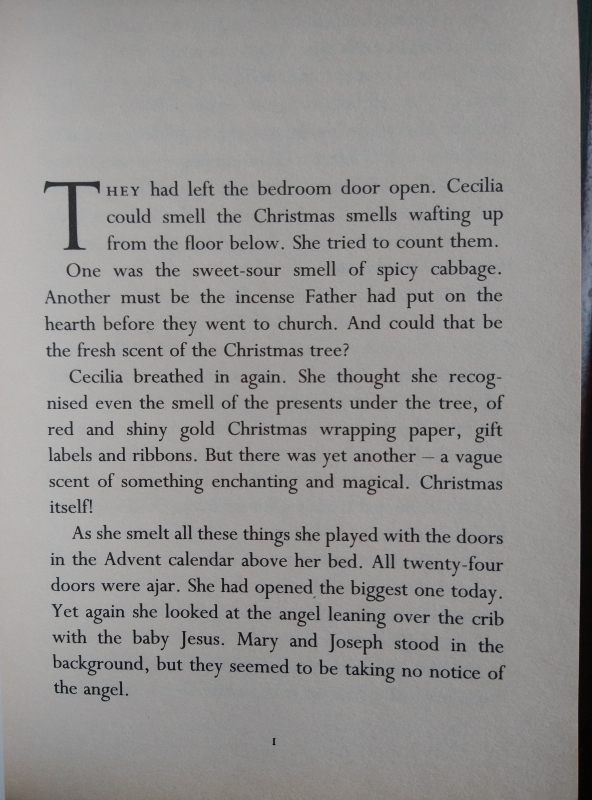

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

Reporting Back on My Most Anticipated Reads of 2024

Most years I’ve combined this topic with a rundown of my DNFs for the year; this time I can’t be bothered to list them. There have maybe not been as many as usual; generally, I’ve given a sentence or two about each DNF in a Love Your Library post. In any case, I hereby give you blanket permission to drop that book you’ve been struggling with. I absolve you of all potential guilt. It makes no difference if it has been nominated for or won a major prize, or if everyone else seems to love it. If for any reason a book isn’t connecting with you, move onto something else; you can always come back to try it another time, or not. Life is short.

So, on to those Most Anticipated books! In January, I picked the 12 new releases I was most looking forward to reading in 2024. Here’s how I fared with them – links are to my reviews:

Read and enjoyed: 5 (2 will appear on my Best-of list!)

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley- Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller

- Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt

- Wellness by Nathan Hill

- Come and Get It by Kiley Reid

Read and found somewhat disappointing (i.e., 3 stars or below): 5

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar- Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

- Exhibit by R.O. Kwon

- The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez

- The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl

DNF: 1

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry

Haven’t managed to get hold of, but have basically decided against anyway: 1

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko – The reviews from Susan and Laura made me realize I probably won’t love this as much as I want to. (Plus the average rating on Goodreads is disconcertingly low.)

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko – The reviews from Susan and Laura made me realize I probably won’t love this as much as I want to. (Plus the average rating on Goodreads is disconcertingly low.)

I’ve really come to wonder if designating a book as “Most Anticipated” is a kiss of death. Are my hopes so high that only the rare book can live up to them?!

Nonetheless, I can’t resist compiling this list each year. In the first week of January, I’ll be previewing my 25 Most Anticipated titles for the first half of 2025.

Do you choose Most Anticipated books each year? (Or do you prefer to be surprised?) And if so, do they generally meet your expectations?

Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

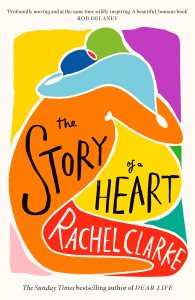

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

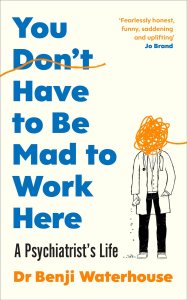

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

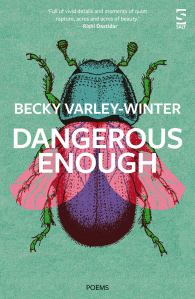

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

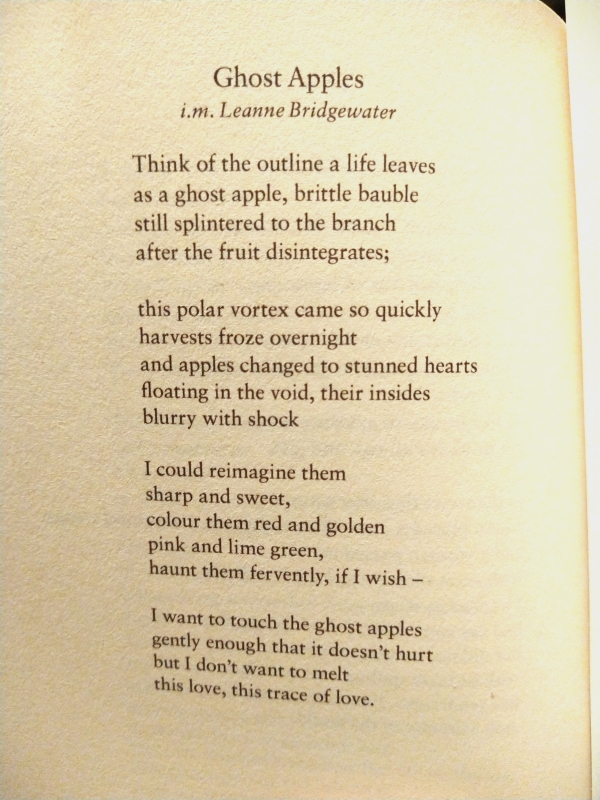

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Cover Love 2024

As I did in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023, I’ve picked out some favourite book covers from the past year’s new releases, about half of which I’ve read. Abstract faces? Colour blocks? Partial female bodies? You never know what will dominate.

I’m sure to be drawn to flora and fauna on book covers, especially when they intertwine uniquely or adapt an artwork.

I also tend to like fruit on a cover. Here is one good example (gorgeous tiles)…

…followed by two awful ones (even though the books themselves, both speculative short story collections I read for paid reviews, were great!). Some will probably love these designs, but the first makes me think of late-1990s clip art and the other is like a crap still life.

I almost always prefer the U.S. cover to the U.K. cover, and the latest Sally Rooney was no exception. Sorry, Faber, but the cover at left does not do the novel justice. Brilliant job, though, Farrar, Straus and Giroux: a perfect way of depicting the central characters and their dynamics via their shadows on a chess board, and having them upside down makes things that little bit off-kilter.

However, the opposite was the case with this Olivia Laing book: the colours and font seem too garish on the Norton edition at left, whereas the blooms slipping through the slats of a white bench on the Picador cover are more elegant and fitting for her style.

I also like a striking font. I loved the contrast between the historical cheekiness of the painting and the contemporary, sans serif, lime green lettering here.

The same goes for the below; I also like that the title goes vertically down the page – a rarer choice.

The rowhouses, the green swoop to simulate the road trip contained therein, the colours, the bold title going over two lines … I have my doubts as to whether this novel can live up to its fabulous packaging:

Similarly, everything about these two covers is fantastic … but the books were DNFs for me, alas:

More themes, or odd ones out

Fractured or distorted faces:

Torn, cut or folded paper:

Overlapping words form a relevant shape:

Pastel kitsch:

But my favourite cover of the year is for Hyper by Agri Ismaïl. The artwork, Doubts? (2020) by Faig Ahmed, is a handmade wool carpet. The cover and title honestly have nothing to do with the contents of the novel, but I love that symbolic melting into abstraction.

On which, see also my close second place. Painterly swirls almost mimic the view through a microscope, and what a classy font, too: Transgenesis by Ava Winter.

(See also Kate’s and Marina Sofia’s book cover posts.)

What cover trends have you noticed this year?

Which ones tend to grab your attention?

The End of the Year Book Tag

I’ve been feeling a little burnt out after Novellas in November, so when I spotted this on Laura’s blog I thought it might be just the thing to help me sort through my December reading plans while I wait to get my reviewing mojo back.

- Is there a book that you started that you still need to finish by the end of the year?

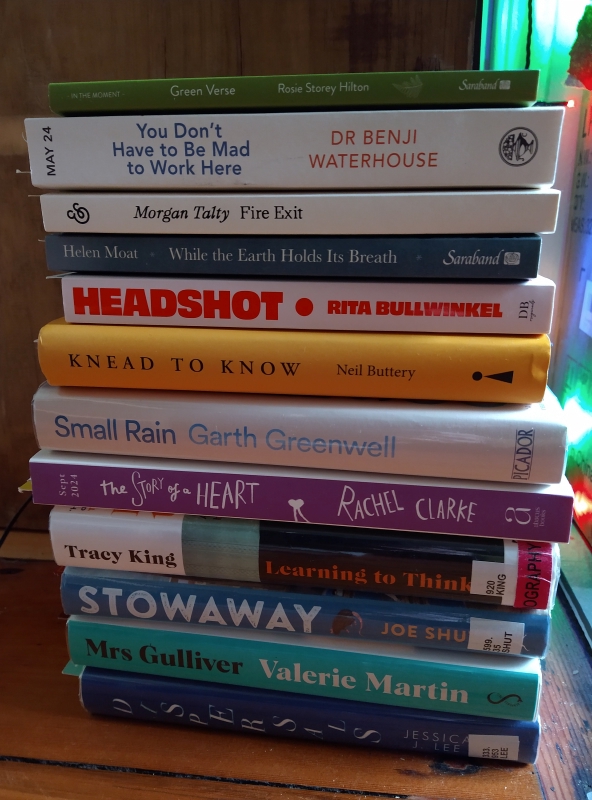

Yes … too many. Pictured are a dozen 2024 releases, a mixture of review copies and library books, that I still hope to get through. Some of them I’m a good way into; others I’ve barely started. (Not shown: All Fours by Miranda July, from NetGalley on my Kindle; and Nine Minds by Daniel Tammet, which I’ll be assessing for Foreword Reviews.)

- Do you have an autumnal book to transition to the end of the year?

Autumn is the hardest season for me to assign reads to. I’m already in winter mode, so it’s more likely that I’ll pick up one or a few of these wintry or Christmassy books.

-

Is there a release you are still waiting for?

Is there a release you are still waiting for?

Published last week and on my Kindle from Edelweiss: the poetry collection Constructing a Witch by Helen Ivory. Otherwise, it’s on to January and February releases for my paid reviewing gigs.

- Name three books you want to read by the end of the year.

From the stack above, I haven’t properly started Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel or opened Fire Exit by Morgan Talty, and I’m still hoping to read those two review copies in their entirety. I will also try to squeeze in at least one more McKitterick Prize novel entry.

But I also have up to five 2025 releases to read for paid reviews that would be due early in January.

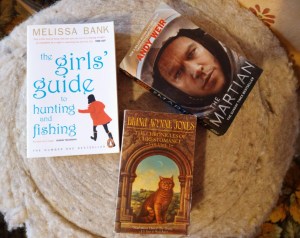

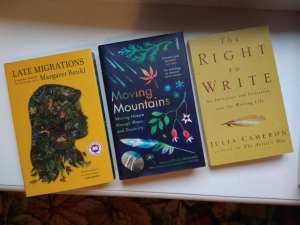

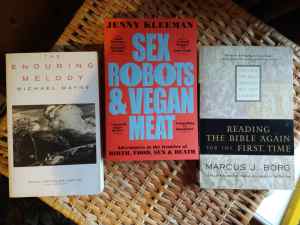

Over the holidays, I fancy dipping into some lighter fiction, cosy and engaging creative nonfiction, and thought-provoking but readable science and theology stuff. Here are some options I pulled off of my bedside table shelves.

- Is there a book that could still shock you and become your favourite of the year?

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell and Dispersals by Jessica J. Lee are both very promising. I’m nearly 1/3 into the Greenwell (it’s my first time reading him) and I’m so impressed: this is patently autofiction about a medical crisis he had during the pandemic, but there is such clarity and granular detail that it feels absolutely true to the record yet soars above any memoir he might have written about the same events. He’s both back in the moment and understanding everything omnisciently. Greenwell has also written poetry, and I was reminded of the Wordsworth quote “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity.”

I’ve only read the first chapter of the Lee so far, but I’m a real fan of her hybrid nature memoirs and I think the metaphorical links between her life and plants will really work.

- Have you already started making reading plans for 2025?

So far I’ve read something like 11 books with 2025 publication dates, most of them for paid reviews. I will feature some of those soon. I’ve also compiled a list of my 20 Most Anticipated releases of 2025 and will post that early in January.

Apart from that, I expect it will be the usual pairs of contradictory goals: reading ahead (2025 stuff) versus catching up (backlist and my preposterous set-aside shelf); failing to resist review copies and library holds versus trying to read more from my own shelves; reading to challenges and themes versus preserving the freedom to pick up books as the whim takes me.

Speaking of themes, I fancy doing a deep dive into the senses, especially the sense of smell, which particularly intrigues me. (I’ll make it a trio with The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell—and the Extraordinary Power of the Nose by Jonas Olofsson, which will be published on 7 January and is on order for me at the library.)

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

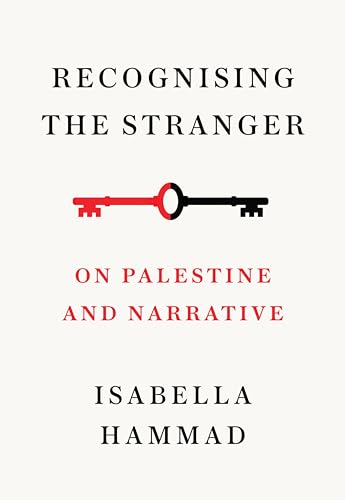

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full  In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness)

In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness) Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full

Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full  Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full

Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy