The Circling Sky & The Sleeping Beauties

I think I have another seven April releases on the go that kind publishers have sent my way, but I’m so slow at finishing books that these two are the only ones I’ve managed so far. (I see lots of review catch-up posts in my future!) For now I have a travel memoir musing on the wonders of the New Forest and the injustice of land ownership policies, and a casebook of medical mysteries that can all be classed as culturally determined psychosomatic illnesses.

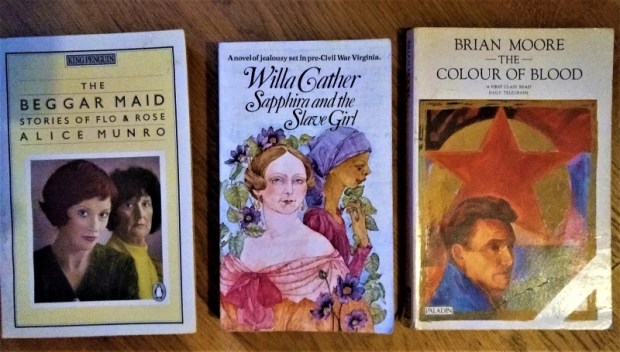

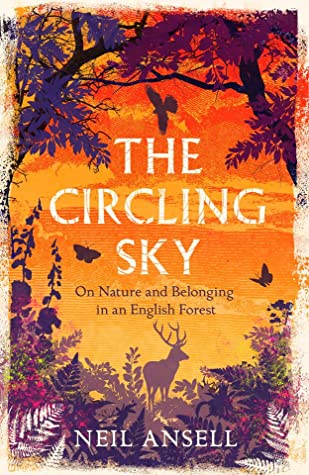

The Circling Sky: On Nature and Belonging in an Ancient Forest by Neil Ansell

After The Last Wilderness and especially Deep Country, his account of five solitary years in a Welsh cabin, Ansell is among my most-admired British nature writers. I was delighted to learn that his new book would be about the New Forest as it’s a place my Hampshire-raised husband and I have visited often and feel fond of. It has personal significance for Ansell, too: he grew up a few miles from Portsmouth. On Remembrance Sunday 1966, though, his family home burned down when a spark from a central heating wire sent the insulation up in flames. He can see how his life was shaped by this incident, making him a nomad who doesn’t accumulate possessions.

Hoping to reclaim a sense of ancestral connection, he returned to the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. The Forest has more than 1000 trees of over 400 years old, mostly oak and beech. Much of the rest is rare heath habitat, and livestock grazing maintains open areas. There are some plants only found in the New Forest, as well as a (probably extinct) cicada. He has close encounters with butterflies, a muntjac, and less-seen birds like the Dartford warbler, firecrest, goshawk, honey buzzard, and nightjar.

But this is no mere ‘white man goes for a walk’ travelogue, as much of modern nature writing has been belittled. Ansell weaves many different themes into the work: his personal story (mostly relevant, though his mother’s illness and a trip to Rwanda seemed less necessary), the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, biomass decline, and especially the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. More than 99% of the country is in the hands of a very few, and hardly any is left as common land. There is also enduring inequality of access to what little there is, often along race and class lines. The have-nots have been taught to envy the haves: “We are all brought up to aspire to home ownership,” Ansell notes. As a long-term renter, it’s a goal I’ve come to question, even as I crave the security and self-determination that owning a house and piece of land could offer.

But this is no mere ‘white man goes for a walk’ travelogue, as much of modern nature writing has been belittled. Ansell weaves many different themes into the work: his personal story (mostly relevant, though his mother’s illness and a trip to Rwanda seemed less necessary), the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, biomass decline, and especially the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. More than 99% of the country is in the hands of a very few, and hardly any is left as common land. There is also enduring inequality of access to what little there is, often along race and class lines. The have-nots have been taught to envy the haves: “We are all brought up to aspire to home ownership,” Ansell notes. As a long-term renter, it’s a goal I’ve come to question, even as I crave the security and self-determination that owning a house and piece of land could offer.

Ansell speaks of “environmental dread” as a “rational response to the way the world is turning,” but he doesn’t rest in that mindset of despair. He’s in favour of rewilding, which is not, as some might assume, about leaving land alone to revert to its original state, but about the reintroduction of native species and intentional restoration of habitat types. In extending these rewilded swathes, we would combat the tendency to think of nature as something kept ‘over there’ in small reserves while subjecting the rest of the land to intensive, pesticide-based farming and the exploitation of resources. The New Forest thus strikes him as an excellent model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access.

I appreciated how Ansell concludes that it’s not enough to simply love nature and write about the joy of spending time in it. Instead, he accepts a mantle of responsibility: “nothing is more political than the way we engage with the world around us. … Nature writing may often be read for comfort and reassurance, but perhaps we need to allow a little room for anger, too, for the ability to rage at everything that has been taken from us, and taken by us.” The bibliography couldn’t be more representative of my ecologist husband’s and my reading interests and nature library. The title is from John Clare and the book is a poetic meditation as well as a forthright argument. It also got me hankering for my next trip to the New Forest.

My rating:

With thanks to Tinder Press for the proof copy for review.

The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness by Suzanne O’Sullivan

O’Sullivan is a consultant at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. She won the Wellcome Book Prize for It’s All in Your Head, and The Sleeping Beauties picks up on that earlier book’s theme of psychosomatic illness – with the key difference being that this one travels around the world to investigate outbreaks of mass hysteria or sickness that have arisen in particular cultural contexts. An important thing to bear in mind is that O’Sullivan and other doctors in her field are not dismissing these illnesses as “fake”; they acknowledge that they are real and meaningful, yet there is clear evidence that they are not physical in origin – brain tests come back normal – but psychological with bodily manifestations.

The case that gives the book its title appeared in Sweden in 2017. Child asylum seekers who had experienced trauma in their home country were falling into a catatonic state. O’Sullivan visited the home of sisters Nola and Helan, part of the Yazidi ethnic minority group from Iraq and Syria. The link between them and the other children affected was that they were all now threatened with deportation: Their hopelessness had taken on physical form, giving the illness the name resignation syndrome. “Predictive coding” meant their bodies did as they expected them to. She describes it as “a very effective culturally agreed means of expressing distress.”

The case that gives the book its title appeared in Sweden in 2017. Child asylum seekers who had experienced trauma in their home country were falling into a catatonic state. O’Sullivan visited the home of sisters Nola and Helan, part of the Yazidi ethnic minority group from Iraq and Syria. The link between them and the other children affected was that they were all now threatened with deportation: Their hopelessness had taken on physical form, giving the illness the name resignation syndrome. “Predictive coding” meant their bodies did as they expected them to. She describes it as “a very effective culturally agreed means of expressing distress.”

In Texas, the author meets Miskito people from Nicaragua who combat the convulsions and hallucinations of “grisi siknis” in their community with herbs and prayers; shamans are of more use in this circumstance than antiepileptic drugs. A sleeping sickness tore through two neighbouring towns of Kazakhstan between 2010 and 2015, affecting nearly half of the population. As with the refugee children in Sweden, it was a stress response to being forced to move away – though people argued they were being poisoned by a local uranium mine. There is often a specific external factor that is blamed in these situations, as when mass hysteria and seizures among Colombian schoolgirls were attributed to the HPV vaccine.

This book was released on the 1st of April, and at times I felt I was the victim of an elaborate April Fool’s joke: the cases are just so bizarre, and we’re used to rooting out a physical cause. But she makes clear that, in a biopsychosocial understanding (as also discussed in Pain by Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen), these illnesses are serving “a vital purpose” – just psychological and cultural. The first three chapters are the strongest; the book feels repetitive and somewhat aimless thereafter, especially in Chapter 4, which hops between different historical outbreaks of psychosomatic illness, like among the Hmong (cf. Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down), and other patients she treated for functional disorders. The later example of “Havana syndrome” doesn’t add enough to warrant its inclusion.

Still, O’Sullivan does well to combine her interviews and travels into compelling mini-narratives. Her writing has really come on in leaps and bounds since her first book, which I found clunky. However, much my favourite of her three works is Brainstorm, about epilepsy and other seizure disorders of various origins.

My rating:

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Women’s Prize Longlist Reviews (Leilani, Lockwood, and Lyon) & Predictions

Tomorrow, Wednesday the 28th, the Women’s Prize shortlist will be revealed. I have read just over half of the longlist so far and have a few more of the nominees on order from the library – though I may cancel one or two of my holds if they don’t advance to the shortlist. Also, my neighbourhood book club has applied to be one of six reading groups shadowing the shortlist this year via a Reading Agency initiative. If I do say so myself, I think we put in a rather strong application. We’ll hear later this week if we’ve been chosen – fingers crossed!

The three longlisted novels I’ve read most recently were all by L authors:

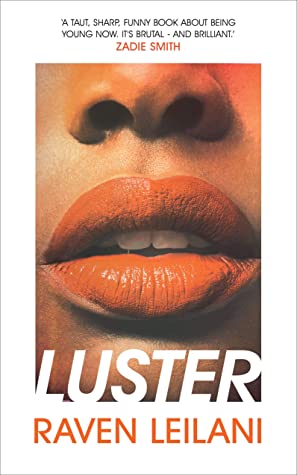

Luster by Raven Leilani

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

As Edie insinuates herself into Eric’s suburban New Jersey life in peculiar and sometimes unwitting ways, we learn more about her traumatic past: Both of her parents are dead, one by suicide, and she had an abortion at age 16. Along with sex, her main escape is her painting, which is described in tender detail. There are a number of amusing scenes set at off-the-wall locations, like a theme park, a clown school, and Comic Con. Leilani has a knack for capturing an entire realm of experience in just a few pages, as when she satirizes current publishing trends or encapsulates what it’s like to be a bicycle delivery person.

But, as a Goodreads acquaintance put it, all this sharp writing is rather wasted on the plot. I found the direction of the book in its second half utterly unrealistic, and never believed that Edie would have found Eric attractive in any way. (His interest in her is beyond creepy, really.) What I found most intriguing, along with the painting hobby, were Edie’s interactions with other Black characters, such as a publishing company colleague and Eric’s adopted daughter – there’s an uncomfortable sense that they should have a natural camaraderie and/or that Edie should be some kind of role model. I might have liked more of that dynamic, instead of the unbearable awkwardness of temporary instalment in a white neighbourhood. Other readalikes: Queenie, Here Is the Beehive, and On Beauty.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Midway through the book, she receives a wake-up call in the form of texts from her mother summoning her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. “It was a marvel how cleanly and completely this lifted her out of the stream of regular life.” Shit just got real, as they say. But “Would it change her?” she asks herself. Apparently, this very thing happened to Lockwood’s own family, which accounts for how heartfelt the second half is – still funny, but with an ache behind it, the same that I sensed and loved in Priestdaddy.

It is the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. As the protagonist tells her students at one point, “Your attention is holy,” and with life so fragile there is no time to waste. What Lockwood is trying to do here is even bigger than that, though, I think. She mocks the whole idea of plot yet takes up the mantle of the “social novel,” as if creating a new format for the Internet-age novel in short, digestible sections. I’m not sure this is as earth-shattering as all that, but it is entertaining and deceptively deep. It also feels like a very current book, playing the role that Weather did in last year’s Women’s Prize race. (See my Goodreads review for more quotes, spoiler-y discussion, and why this book held personal poignancy for me.)

Consent by Annabel Lyon

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

For much of the novel, Lyon bounces between the two storylines. I occasionally confused Sara and Saskia, but I think that’s part of the point (why else would an author select two S-a names?) – their stories overlap as they find themselves in the position of making decisions on behalf of an incapacitated sister. The title invites deliberation about how control is parcelled out in these parallel situations, but I’m not sure consent was the right word to encapsulate the whole plot; it seems to give too much importance to some fleeting sexual relationships.

At times I found Lyon’s prose repetitive or detached, but I enjoyed the overall dynamic and the medical threads. There are some stylish lines that land perfectly, like “There she goes … in her lovely coat, that cashmere-and-guilt blend so few can afford. That lovely perfume she trails, lilies and guilt.” The Vancouver setting and French–English bilingualism, not things I often encounter in fiction, were also welcome, and the last few chapters are killer.

The other nominees I’ve read, with ratings and links to reviews, are:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

The rest of the longlist is:

- Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers – I might read this from the library.

- The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig – I’d thought I’d give this one a miss, but I recently found a copy in a Little Free Library. My plan is to read it later in the year as part of a Patricia Highsmith kick, but I’ll move it up the stack if it makes the shortlist.

- Because of You by Dawn French – Not a chance. Right? Please!

- How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones – A DNF; I would only try it again from the library if it was shortlisted.

- Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon – I might read this from the library.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – I will definitely read this from the library.

- Summer by Ali Smith – I struggle with her work and haven’t enjoyed this series; I would only read this if it was shortlisted and my book club was assigned it!

My ideal shortlist (a wish list based on my reading and what I still want to read):

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

vs.

My predicted shortlist and reasoning:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi – Others don’t seem to fancy Doshi’s chances, and it’s true that she was already shortlisted for the Booker, but I feel like this could be more unifying a choice for the judges than, e.g. Clarke or Lockwood.

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi – Another definite.

- Luster by Raven Leilani – Not as strong as the Dolan, in my opinion, but it seems to have a lot of love from these judges (especially Vick Hope, who emphasized how perfectly it captured what it’s like to be young today), and from critics generally.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – Ordinarily I would have said the Prize is too staid to shortlist a trans author, but after all the online abuse that has been directed at Peters, I think the judges will want to make a stand in support of her legitimacy.

- Summer by Ali Smith – The most establishment author on the list, and not one I generally care for, but this would be a way of recognizing the four-part Seasons opus and her work in general. Of the middle-aged white cohort, she seems most likely.

I will happily accept some mixture of my wished-for and predicted titles, and would be surprised if any of the five books I have not mentioned is shortlisted. (Though quite a few others are predicting that Claire Fuller will advance; I’d have no problem with that.) I don’t think my book club would get a say in which of the six titles we’d be sent to read for the shadowing project, which is risky as I may have already read it and not want to reread, or it may be a surprise nominee that I don’t want to read, but I’ll cross that bridge if we come to it.

Callum, Eric, Laura and Rachel have been posting lots of reviews and thoughts related to the Women’s Prize. Have a look at their blogs!

Rachel also produced a priceless spreadsheet of all the Prize nominees by year, so you can tick off the ones you’ve read. I’m up to 150 now!

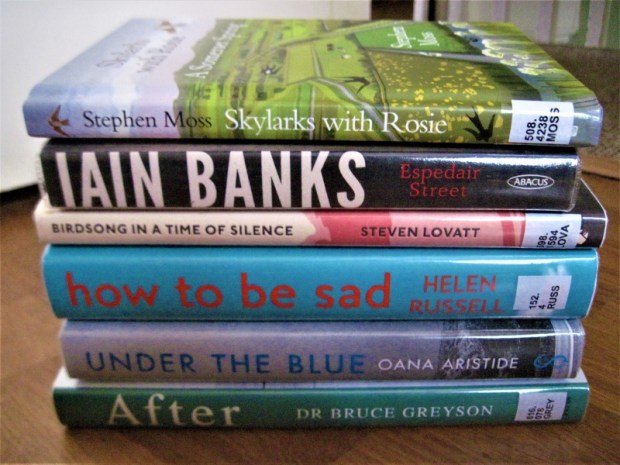

Library Checkout, April 2021

Over the past month, my library reading has included a few more novels from the Women’s Prize longlist and several memoirs, a few of them reflecting on the events of 2020. I also picked out a stack of picture books, most of them cat-themed, while looking for reservations (I’ve been back to volunteering at the library twice weekly).

I give links to reviews of books I haven’t already featured, as well as ratings for most reads and skims. I would be delighted to have other bloggers join in with this meme. Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (the last Monday of each month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram: @bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout & #LoveYourLibraries.

READ

- Luster by Raven Leilani – review coming up tomorrow

- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood – review coming up tomorrow

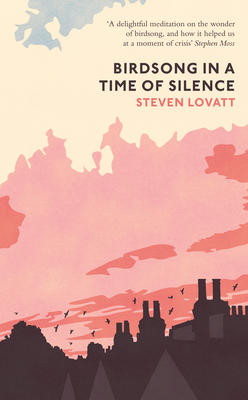

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- Consent by Annabel Lyon – review coming up tomorrow

- Skylarks with Rosie: A Somerset Spring by Stephen Moss

- How We Met: A Memoir of Love and Other by Huma Qureshi

- UnPresidented: Politics, Pandemics and the Race that Trumped All Others by Jon Sopel

- Asylum Road by Olivia Sudjic

- When God Was a Rabbit by Sarah Winman

Also these children’s picture books, which don’t count towards my year totals.

-

- Alfie in the Garden by Debi Gliori

- The Poesy Ring by Bob Graham

- The Mice in the Churchyard by Kes Gray

- Captain Cat by Inga Moore

- Pussy Cat, Pussy Cat, Where Have You Been? I’ve Been to Washington and Guess What I’ve Seen by Russell Punter

- Fred by Posy Simmonds

- Alfie in the Garden by Debi Gliori

SKIMMED

- The Natural Health Service: What the Great Outdoors Can Do for Your Mind by Isabel Hardman

- The Librarian by Allie Morgan

CURRENTLY READING

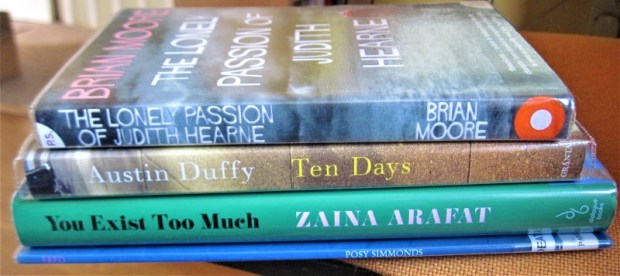

- You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

- Ten Days by Austin Duffy

- Featherhood: On Birds and Fathers by Charlie Gilmour

- The Last Migration by Charlotte McConaghy

- Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story by Paul Monette

- The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore

- Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley

- You’re Not Listening: What You’re Missing and Why It Matters by Kate Murphy

- Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

- Woods etc. by Alice Oswald

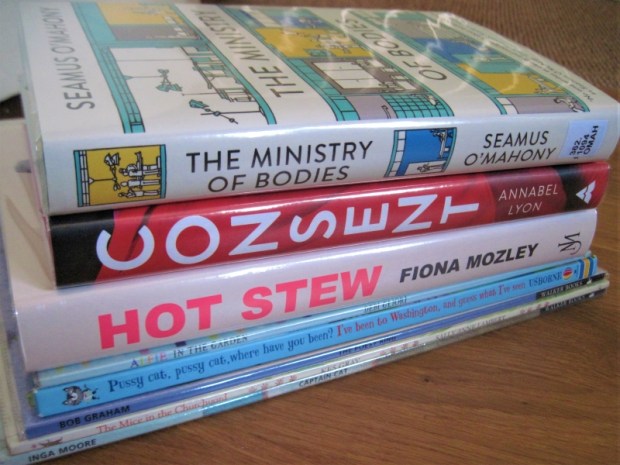

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond by Bruce Greyson

- The Ministry of Bodies: Life and Death in a Modern Hospital by Seamus O’Mahony

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Under the Blue by Oana Aristide

- The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal about Identity, Race, Wealth and Power by Deirdre Mask

- The Pleasure Steamers by Andrew Motion

- How to Be Sad: Everything I’ve Learned about Getting Happier, by Being Sad, Better by Helen Russell

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Who Is Maud Dixon? by Alexandra Andrews

- Failures of State: The Inside Story of Britain’s Battle with Coronavirus by Jonathan Calvert and George Arbuthnott

- Life Support: Diary of an ICU Doctor on the Frontline of the COVID Crisis by Jim Down

- The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- Life Sentences by Billy O’Callaghan

- Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS by Michael Rosen

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Civilisations by Laurent Binet

- This Happy by Niamh Campbell

- Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers

- Heavy Light: A Journey through Madness, Mania and Healing by Horatio Clare

- The Madness of Grief: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Reverend Richard Coles

- Darwin’s Dragons by Lindsay Galvin

- Lakewood by Megan Giddings

- The Rome Plague Diaries: Lockdown Life in the Eternal City by Matthew Kneale

- Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon

- Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

- Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

- My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

- I Belong Here: A Journey along the Backbone of Britain by Anita Sethi

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

- When We Went Wild by Isabella Tree and Allira Tee

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Escape Routes by Naomi Ishiguro – I read and enjoyed a few stories, but didn’t feel the need to read any more (especially some very long or fantasy-looking ones).

- The Art of Falling by Danielle McLaughlin

RETURNED UNREAD

- A Tall History of Sugar by Curdella Forbes – Seemed like it might be tiresome (too involved, too much backstory, etc.).

- Double Blind by Edward St. Aubyn – Ponderous writing in the first few pages, and too many middling or negative reviews from friends on Goodreads.

What appeals from my stacks?

BanksRead 2021: Espedair Street (1987)

The dead end just off Lonely Street

It’s where you go, after Desperation Row

Espedair Street

I had my first taste of Iain Banks’s work last year with The Crow Road and was glad to have an excuse to read more by him for Annabel’s BanksRead challenge.

I had my first taste of Iain Banks’s work last year with The Crow Road and was glad to have an excuse to read more by him for Annabel’s BanksRead challenge.

I chose Espedair Street, which was in surprisingly high demand at my local library: I was in the middle of a queue of five people waiting for a novel released nearly 35 years ago! Luckily, the system’s single copy came in for me in early April.

This was Banks’s fourth novel. I recognized the Glasgow and western Scotland settings and witty dialogue as recurring elements. The Scottish dialect and slang were somehow easier to deal with here than in books like Shuggie Bain. Daniel Weir (nicknamed “Weird”) is a former rock star, washed up though only in his early thirties and contemplating suicide. He has all the money he could ever want, but his relationships seem to have fizzled.

Dan takes us back to the start of his time with the band Frozen Gold in the 1970s. He acknowledges that he only ever had limited musical talent; although he can play the bass well enough, his real gift is for lyrics. Songwriting was mostly what he had to offer when he met bandmates Dave and Christine after their gig at the Union:

What am I doing here? I thought once more. They don’t need me, no matter how good the songs are. They’ll always be heading in different directions, moving in different circles, higher spheres. Jesus, this was life or death to me, my one chance to make the great working class escape. I couldn’t play football; what other hope was there to get into the supertax bracket?

Boldly, he told them that night that they were a good covers band but needed their own material, and he had sheaves of songs at the ready. From here, it was an unlikely road to a world tour in 1980, but a perhaps more predictable slide into the alcohol abuse and gratuitous displays of wealth that will leave Dan questioning what of true value he retains.

Dan’s voice, as in the passage above, is mischievous yet confessional. The sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll theme made me think of Taylor Jenkins Reid’s Daisy Jones & the Six, a rather more enjoyable novel for its interview format and multiple perspectives, but both include pleasing made-up lyrics. Here Dan’s frequent use of ellipses threatened to drive me mad. It might seem a small thing but it’s one of my pet peeves.

I think I’ll make The Bridge my next from Banks – my library owns a copy, and he called it his favourite of his books.

Do check out all of Annabel’s coverage from the past week: she’s given a great sense of the breadth of Banks’s work, from science fiction to poetry.

The 1936 Club: Murder in the Cathedral and Ballet Shoes

It’s my third time participating in one of Simon and Karen’s reading weeks (after last year’s 1920 Club and 1956 Club). Like last time, I made things easy for myself by choosing two classics of novella length – as opposed to South Riding, another 1936 book on my shelves. They also both happen to be theatrical in nature.

Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot

At about the time her memoir came out, I remember Jeanette Winterson describing this as her gateway drug into literature: she went to the library and picked it out for her mother, thinking it was just another murder mystery, and ended up devouring it herself. It is in fact a play about the assassination of Thomas à Becket, a medieval archbishop of Canterbury. The last time I read a play was probably eight years ago, when I was on an Alan Ayckbourn kick; before that, I likely hadn’t read one since my college Shakespeare class. And indeed, this wasn’t dissimilar to Shakespeare’s histories (or tragedies) in content and tone. It is mostly in verse, with some rhyming couplets, offset by a couple of long prose passages.

At about the time her memoir came out, I remember Jeanette Winterson describing this as her gateway drug into literature: she went to the library and picked it out for her mother, thinking it was just another murder mystery, and ended up devouring it herself. It is in fact a play about the assassination of Thomas à Becket, a medieval archbishop of Canterbury. The last time I read a play was probably eight years ago, when I was on an Alan Ayckbourn kick; before that, I likely hadn’t read one since my college Shakespeare class. And indeed, this wasn’t dissimilar to Shakespeare’s histories (or tragedies) in content and tone. It is mostly in verse, with some rhyming couplets, offset by a couple of long prose passages.

I struggled mostly because of complete unfamiliarity with the context, though some liberal Googling would probably be enough to set anyone straight. The action takes place in December 1170 and is in two long acts, separated by an interlude in which Thomas gives a Christmas sermon. The main characters besides Thomas are three priests who try to protect him and a chorus of local women who lament his fate. In Part I there are four tempters who, like Satan to Jesus in the desert, come to taunt Thomas with the lure of political power – upon being named archbishop, he resigned his chancellorship. The four knights, who replace the tempters in Part II and ultimately kill Thomas, feel that he betrayed King Henry and the nation by not keeping both roles and thus linking Church and state.

Most extraordinary is the knights’ prose defence late in the second act, in which they claim to have been completely “disinterested” in killing Thomas and that it was his own fault – to the extent that his death might as well be deemed a suicide. I always appreciate a first-person plural chorus, and I love Eliot’s poetry in general: there are some of his lines I keep almost as mantras, and more I read nearly 20 years ago that still resonate. I expected notable quotes here, but there were no familiar lines. As usually is the case with plays, this probably works better on stage. A nice touch was that my 1938 Faber copy, acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in our local mall, was owned by two fellows of St. Chad’s College, Durham, whose names appear one after the other in blue ink on the flyleaf. One of them added in marginal notes relating to how the play was performed by the Pilgrim Players in March 1941.

My rating:

Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild

I was glad to have an excuse to read this beloved children’s classic. Like many older books and films geared towards children, it’s a realistic fantasy about orphans finding affection and success. Great-Uncle Matthew (“Gum”) goes hunting for fossils around the world and has a peculiar habit of finding unwanted babies that are to be raised by his niece, Sylvia (“Garnie”), and a nursemaid, Nana. He names the three girls he has magically acquired Pauline, Petrova, and Posy, and gifts them all the surname Fossil. When Gum goes back out on his travels, the money soon runs out and the girls’ schooling takes a backseat to the need for money. Sylvia takes in lodgers and the girls are accepted to attend a dance and theatre academy for free.

Every year, the sisters vow to do all they can to get the Fossil name in history books – and this on their own merit, not based on anything their (unknown) ancestors have done – and to get as much household money for Garnie as possible. Pauline is a gifted actress and Posy a talented dancer, but Petrova knows the performing world is not for her; she’d rather learn about how machines work, and operate cars and airplanes. While beautiful blonde Pauline plays the lead role in Alice in Wonderland and one of the princes in Richard III, Petrova is happy to stay in the background as a fairy or a page in Shakespeare productions.

Every year, the sisters vow to do all they can to get the Fossil name in history books – and this on their own merit, not based on anything their (unknown) ancestors have done – and to get as much household money for Garnie as possible. Pauline is a gifted actress and Posy a talented dancer, but Petrova knows the performing world is not for her; she’d rather learn about how machines work, and operate cars and airplanes. While beautiful blonde Pauline plays the lead role in Alice in Wonderland and one of the princes in Richard III, Petrova is happy to stay in the background as a fairy or a page in Shakespeare productions.

I found the social history particularly interesting here. The family seems upper class by nature, yet a lack of money means they find it a challenge to keep the girls in an appropriate wardrobe. There is much counting of guineas and shillings, with Pauline the chief household earner. Acting in plays and films is no mere hobby for her. The same goes for Winifred, who auditions opposite Pauline for Alice but doesn’t get the part – even though she is the better actress and needs the money to care for her ill father and five younger siblings – because she’s not as pretty. Pauline and Petrova also notice that child actors with cockney accents don’t get picked for the best roles. The Fossils sometimes feel compassion for those children worse off than themselves, but at other times let their achievements go to their heads.

At a certain point, I wearied of the recurring money, wardrobe, and audition issues, but I still found this a charming book about how luck and skill combine as girls dream about who they want to be when they grow up. There are also some cosy and witty turns of phrase, like “She was in that state of having a cold when nothing is very nice to do … she felt hot, and not very much like eating toffee, and what is the fun of making toffee unless you want to eat it.” I daresay if I had encountered this at age seven instead of 37, it would have been a favourite.

My rating:

An unfortunate misunderstanding soon arises between Judith and James: in no time she’s imagining romantic scenarios, whereas he, wrongly suspecting she has money stashed away, hopes she can be lured into investing in his planned American-style diner in Dublin. “A pity she looks like that,” he thinks. Later we get a more detailed description of Judith from a bank cashier: “On the wrong side of forty with a face as plain as a plank, and all dressed up, if you please, in a red raincoat, a red hat with a couple of terrible-looking old wax flowers in it.”

An unfortunate misunderstanding soon arises between Judith and James: in no time she’s imagining romantic scenarios, whereas he, wrongly suspecting she has money stashed away, hopes she can be lured into investing in his planned American-style diner in Dublin. “A pity she looks like that,” he thinks. Later we get a more detailed description of Judith from a bank cashier: “On the wrong side of forty with a face as plain as a plank, and all dressed up, if you please, in a red raincoat, a red hat with a couple of terrible-looking old wax flowers in it.”

During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, from Birmingham and now based in South Wales, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. (He even gives step-by-step instructions for sounding like a magpie.) Birdsong takes him back to childhood, but feels deeper than that: a cultural memory that enters into our poetry and will be lost forever if we allow our declining bird species to continue on the same trajectory.

During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, from Birmingham and now based in South Wales, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. (He even gives step-by-step instructions for sounding like a magpie.) Birdsong takes him back to childhood, but feels deeper than that: a cultural memory that enters into our poetry and will be lost forever if we allow our declining bird species to continue on the same trajectory. Lovatt must have been a pupil of Moss’s on the Bath Spa University MA degree in Travel and Nature Writing. The prolific Moss’s latest also reflects on the spring of 2020, but in a more overt diary format. Devoting one chapter to each of the 13 weeks of the first lockdown, he traces the season’s development alongside his family’s experiences and the national news. With four of his children at home, along with one of their partners and a convalescing friend, it’s a pleasingly full house. There are daily cycles or walks around “the loop,” a three-mile circuit from their front door, often with Rosie the Labrador; there are also jaunts to corners of the nearby Avalon Marshes. Nature also comes to him, with songbirds in the garden hedges and various birds of prey flying over during their 11:00 coffee breaks.

Lovatt must have been a pupil of Moss’s on the Bath Spa University MA degree in Travel and Nature Writing. The prolific Moss’s latest also reflects on the spring of 2020, but in a more overt diary format. Devoting one chapter to each of the 13 weeks of the first lockdown, he traces the season’s development alongside his family’s experiences and the national news. With four of his children at home, along with one of their partners and a convalescing friend, it’s a pleasingly full house. There are daily cycles or walks around “the loop,” a three-mile circuit from their front door, often with Rosie the Labrador; there are also jaunts to corners of the nearby Avalon Marshes. Nature also comes to him, with songbirds in the garden hedges and various birds of prey flying over during their 11:00 coffee breaks. For Halle, who worked in the State Department, nature was an antidote to hours spent shuffling papers behind a desk. In this spring of 1945, there was plenty of wildfowl to see in central D.C. itself, but he also took long early morning bike rides along the Potomac or the C&O Canal, or in Rock Creek Park. From first migrant in February to last in June, he traces the spring mostly through the birds that he sees. More so than the specific observations of familiar places, though, I valued the philosophical outlook that makes Halle a forerunner of writers like Barry Lopez and Peter Matthiessen. He notes that those caught up in the rat race adapt the world to their comfort and convenience, prizing technology and manmade tidiness over natural wonders. By contrast, he feels he sees more clearly – literally as well as metaphorically – when he takes the long view of a landscape.

For Halle, who worked in the State Department, nature was an antidote to hours spent shuffling papers behind a desk. In this spring of 1945, there was plenty of wildfowl to see in central D.C. itself, but he also took long early morning bike rides along the Potomac or the C&O Canal, or in Rock Creek Park. From first migrant in February to last in June, he traces the spring mostly through the birds that he sees. More so than the specific observations of familiar places, though, I valued the philosophical outlook that makes Halle a forerunner of writers like Barry Lopez and Peter Matthiessen. He notes that those caught up in the rat race adapt the world to their comfort and convenience, prizing technology and manmade tidiness over natural wonders. By contrast, he feels he sees more clearly – literally as well as metaphorically – when he takes the long view of a landscape. I marked so many passages of beautiful description. Halle had mastered the art of noticing. But he also sounds a premonitory note, one that was ahead of its time in the 1940s and needs heeding now more than ever: “When I see men able to pass by such a shining and miraculous thing as this Cape May warbler, the very distillate of life, and then marvel at the internal-combustion engine, I think we had all better make ourselves ready for another Flood.”

I marked so many passages of beautiful description. Halle had mastered the art of noticing. But he also sounds a premonitory note, one that was ahead of its time in the 1940s and needs heeding now more than ever: “When I see men able to pass by such a shining and miraculous thing as this Cape May warbler, the very distillate of life, and then marvel at the internal-combustion engine, I think we had all better make ourselves ready for another Flood.” More cherry blossoms over tourist landmarks! This is part of a children’s series inspired by the 1805 English rhyme about London; other volumes visit New York City, Paris, and Rome. In rhyming couplets, he takes us from the White House to the Lincoln Memorial via all the other key sights of the Mall and further afield: museums and monuments, the Library of Congress, the National Cathedral, Arlington Cemetery, even somewhere I’ve never been – Theodore Roosevelt Island. Realism and whimsy (a kid-sized cat) together; lots of diversity in the crowd scenes. What’s not to like? (Titled Kitty cat, kitty cat… in the USA.)

More cherry blossoms over tourist landmarks! This is part of a children’s series inspired by the 1805 English rhyme about London; other volumes visit New York City, Paris, and Rome. In rhyming couplets, he takes us from the White House to the Lincoln Memorial via all the other key sights of the Mall and further afield: museums and monuments, the Library of Congress, the National Cathedral, Arlington Cemetery, even somewhere I’ve never been – Theodore Roosevelt Island. Realism and whimsy (a kid-sized cat) together; lots of diversity in the crowd scenes. What’s not to like? (Titled Kitty cat, kitty cat… in the USA.)  Like a Murakami protagonist, Taro is a divorced man in his thirties, mildly interested in the sometimes peculiar goings-on in his vicinity. Rumor has it that his Tokyo apartment complex will be torn down soon, but for now the PR manager is happy enough here. “Avoiding bother was Taro’s governing principle.” But bother comes to find him in the form of a neighbor, Nishi, who is obsessed with a nearby house that was the backdrop for the art book Spring Garden, a collection of photographs of a married couple’s life. Her enthusiasm gradually draws Taro into the depicted existence of the TV commercial director and actress who lived there 25 years ago, as well as the young family who live there now. This Akutagawa Prize winner failed to hold my interest – like

Like a Murakami protagonist, Taro is a divorced man in his thirties, mildly interested in the sometimes peculiar goings-on in his vicinity. Rumor has it that his Tokyo apartment complex will be torn down soon, but for now the PR manager is happy enough here. “Avoiding bother was Taro’s governing principle.” But bother comes to find him in the form of a neighbor, Nishi, who is obsessed with a nearby house that was the backdrop for the art book Spring Garden, a collection of photographs of a married couple’s life. Her enthusiasm gradually draws Taro into the depicted existence of the TV commercial director and actress who lived there 25 years ago, as well as the young family who live there now. This Akutagawa Prize winner failed to hold my interest – like