Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

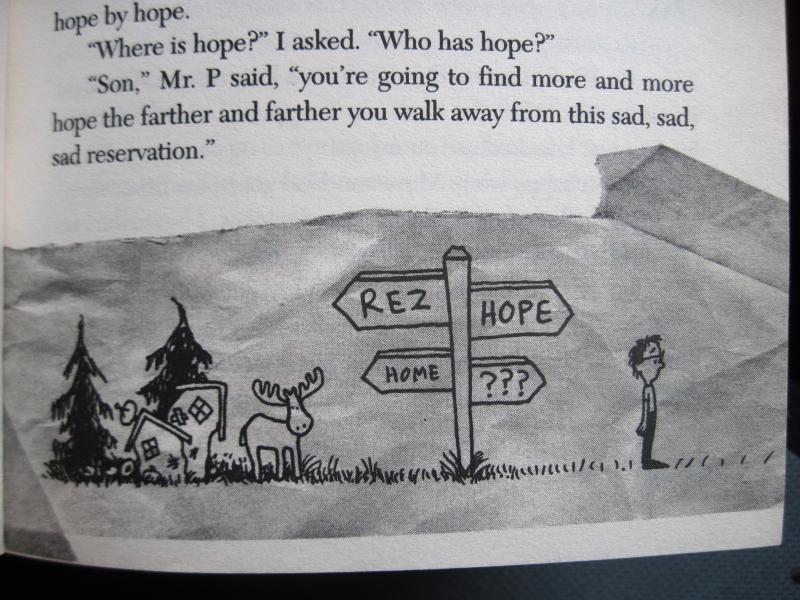

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Winter Reads: Claire Tomalin, Daniel Woodrell & Picture Books

Mid-February approaches and we’re wondering if the snowdrops and primroses emerging here in the South of England mean that it will be farewell to winter soon, or if the cold weather will return as rumoured. (Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow, but that early-spring prediction is only valid for the USA, right?) I didn’t manage to read many seasonal books this year, but I did pick up several short works with “Winter” in the title: a little-known biographical play from a respected author, a gritty Southern Gothic novella made famous through a Jennifer Lawrence film, and two picture books I picked up at the library last week.

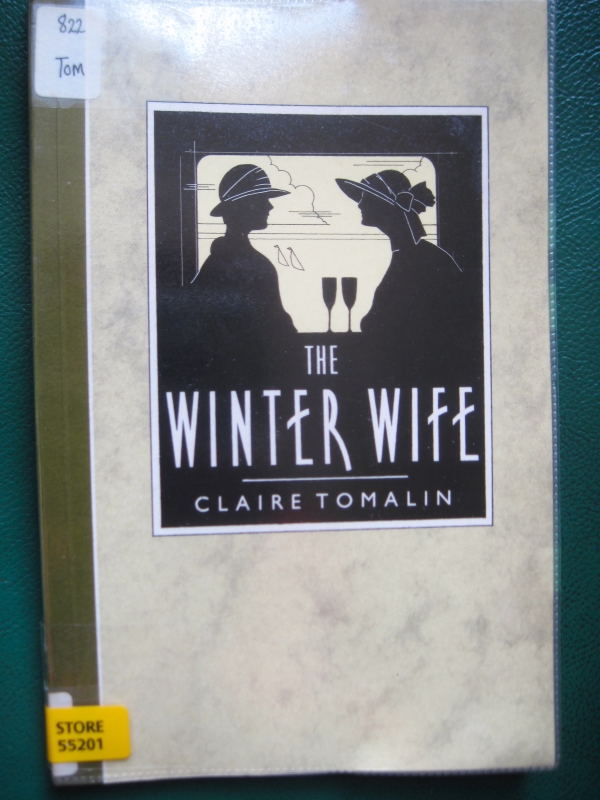

The Winter Wife by Claire Tomalin (1991)

A search of the university library catalogue turned up this Tomalin title I’d never heard of. It turns out to be a very short play (two acts of seven scenes each, but only running to 44 pages in total) about a trip abroad Katherine Mansfield took with her housekeeper?/companion, Ida Baker, in 1920. Ida clucks over Katherine like a nurse or mother hen, but there also seems to be latent, unrequited love there (Mansfield was bisexual, as I knew from fellow New Zealander Sarah Laing’s fab graphic memoir Mansfield and Me). Katherine, for her part, alternately speaks to Ida, whom she nicknames “Jones,” with exasperation and fondness. The title comes from a moment late on when Katherine tells Ida “you’re the perfect friend – more than a friend. You know what you are, you’re what every woman needs: you’re my true wife.” Maybe what we’d call a “work wife” today, but Ida blushes with pride.

Tomalin had already written a full-length biography of Mansfield, but insists she barely referred to it when composing this. The backdrops are minimal: a French sleeper train; Isola Bella, a villa on the French Riviera; and Dr. Bouchage’s office. Mansfield was ill with tuberculosis, and the continental climate was a balm: “The sun gets right into my bones and makes me feel better. All that English damp was killing me. I can’t think why I ever tried to live in England.” There are also financial worries. The Murrys keep just one servant, Marie, a middle-aged French woman who accompanies her on this trip, but Katherine fears they’ll have to let her go if she doesn’t keep earning by her pen.

Through Katherine’s conversations with the doctor, we catch up on her romantic history – a brief first marriage, a miscarriage, and other lovers. Dr. Bouchage believes her infertility is a result of untreated gonorrhea. He echoes Ida in warning Katherine that she’s working too hard – mostly reviewing books for her husband John Middleton Murry’s magazine, but also writing her own short stories – when she should be resting. Katherine retorts, “It is simply none of your business, Jones. Dr Bouchage: if I do not work, I might as well be dead, it’s as simple as that.”

She would die not three years later, a fact that audiences learn through a final flash-forward where Ida, in a monologue, contrasts her own long life (she lived to 90 and Tomalin interviewed her when she was 88) with Katherine’s short one. “I never married. For me, no one ever equalled Katie. There was something golden about her.” Whereas Katherine had mused, “I thought there was going to be so much life then … that it would all be experience I could use. I thought I could live all sorts of different lives, and be unscathed…”

The play is, by its nature, slight, but gives a lovely sense of the subject and her key relationships – I do mean to read more by and about Mansfield. I wonder if it has been performed much since. And how about this for unexpected literary serendipity?

Yes, it’s that Rachel Joyce. (University library)

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

Forced to undertake a frozen odyssey to find traces of Jessup, she’s unwelcome everywhere she goes, even among extended family. No one is above hitting a girl, it seems, and just for asking questions Ree gets beaten half to death. Her only comfort is in her best friend, Gail, who’s recently given birth and married the baby daddy. Gail and Ree have long “practiced” on each other romantically. Without labelling anything, Woodrell sensitively portrays the different value the two girls place on their attachment. His prose is sometimes gorgeous –

Pine trees with low limbs spread over fresh snow made a stronger vault for the spirit than pews and pulpits ever could.

– but can be overblown or off-puttingly folksy:

Ree felt bogged and forlorn, doomed to a spreading swamp of hateful obligations.

Merab followed the beam and led them on a slow wamble across a rankled field

This was my second from Woodrell, after the short stories of The Outlaw Album. I don’t think I’ll need to try any more by him, but this was a solid read. (Secondhand – New Chapter Books, Wigtown)

Children’s picture books:

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

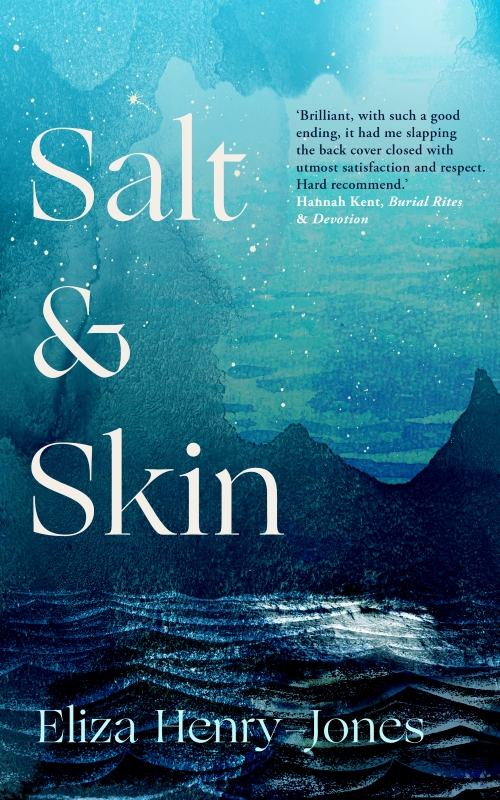

Salt & Skin by Eliza Henry-Jones (Blog Tour)

I was drawn to Eliza Henry-Jones’s fifth novel, Salt & Skin (2022), by the setting: the remote (fictional) island of Seannay in the Orkneys. It tells the dark, intriguing story of an Australian family lured in by magic and motivated by environmentalism. History overshadows the present as they come to realize that witch hunts are not just a thing of the past. This was exactly the right evocative reading for me to take on my trip to some other Scottish islands late last month. The setup reminded me of The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel, while the novel as a whole is reminiscent of The Night Ship by Jess Kidd and Night Waking by Sarah Moss.

Only a week after the Managans – photographer Luda, son Darcy, 16, and daughter Min, 14 – arrive on the island, they witness a hideous accident. A sudden rockfall crushes a little girl, and Luda happens to have captured it all. The photos fulfill her task of documenting how climate change is affecting the islands, but she earns the locals’ opprobrium for allowing them to be published. It’s not the family’s first brush with disaster. The kids’ father died recently; whether in an accident or by suicide is unclear. Nor is it the first time Luda’s camera has gotten her into trouble. Darcy is still angry at her for selling a photograph she took of him in a dry dam years before, even though it raised a lot of money and awareness about drought.

The family live in what has long been known as “the ghost house,” and hints of magic soon seep in. Luda’s archaeologist colleague wants to study the “witch marks” at the house, and Darcy is among the traumatized individuals who can see others’ invisible scars. Their fate becomes tied to that of Theo, a young man who washed up on the shore ten years ago as a web-fingered foundling rumoured to be a selkie. Luda becomes obsessed with studying the history of the island’s witches, who were said to lure in whales. Min collects marine rubbish on her deep dives, learning to hold her breath for improbable periods. And Darcy fixates on Theo, who also attracts the interest of a researcher seeking to write a book about his origins.

It’s striking how Henry-Jones juxtaposes the current and realistic with the timeless and mystical. While the climate crisis is important to the framework, it fades into the background as the novel continues, with the focus shifting to the insularity of communities and outlooks. All of the characters are memorable, including the Managans’ elderly relative, Cassandra (calling to mind a prophetic figure from Greek mythology), though I found Father Lee, the meddlesome priest, aligned too readily with clichés. While the plot starts to become overwrought in later chapters, I appreciated the bold exploration of grief and discrimination, the sensitive attention to issues such as addiction and domestic violence, and the frank depictions of a gay relationship and an ace character. I wouldn’t call this a cheerful read by any means, but its brooding atmosphere will stick with me. I’d be keen to read more from Henry-Jones.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and September Publishing for the free copy for review.

Buy Salt & Skin from the Bookshop UK site. [affiliate link]

or

Pre-order Salt & Skin (U.S. release: September 5) from Bookshop.org. [affiliate link]

I was delighted to help kick off the blog tour for Salt & Skin on its UK publication day. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Poetry Review Catch-up: Burch, Carrick-Varty, Davidson, Marya, Parsons (#ReadIndies)

As Read Indies month continues, I’m catching up on poetry collections I’ve been sent by three independent publishers: the UK’s Carcanet Press, and Alice James Books and Terrapin Press, both based in the USA. Various as these five are in style and technique, nature and family ties are linking themes. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

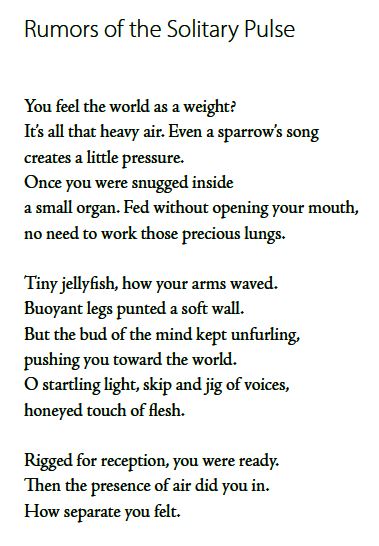

Leave Me a Little Want by Beverly Burch (2022)

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty (2023)

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Arctic Elegies by Peter Davidson (2022)

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Wonderful is the patience of the snow

And glorious the violence of the cold.

How lovely is the power of the dark pole

To draw the iron and move the compass rose.

As cold as loss as cold as freezing steel

In this same vein, I also appreciated the wry “The Museum of Loss” and the ornate “The Mourning Virtuoso.” There’s a bit of an Auden flavour here, but the niche topics didn’t always hold my attention.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

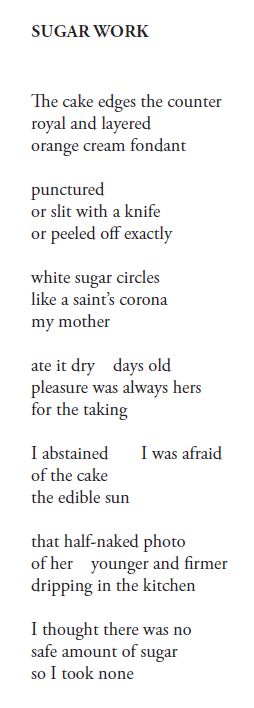

Sugar Work by Katie Marya (2022)

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

With thanks to Alyson Sinclair PR for the free e-copy for review.

The Mayapple Forest by Kim Ports Parsons (2022)

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

I read this after its shortlisting for the Charlotte Aitken Trust/Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, as well as its longlisting for the Dylan Thomas Prize. It is a truth universally acknowledged that any novel by a young Irish woman will only and ever be compared to Sally Rooney … but that works in Nolan’s favour. I would certainly call this a readalike to Rooney’s first two books, but there’s an added psychological intensity here.

A young woman reflects on an obsessive affair that she began in Dublin in April 2012. Was it love at first sight for her with Ciaran? No, actually, it was more like pity: “The first time I saw him, I pitied him terribly,” the novel opens. “I stood in that gallery and felt not only sexual attraction (which I was aware of, dimly, as background noise) but what I can only describe as grave and troubling pity.” That doesn’t bode well now, does it?

A young woman reflects on an obsessive affair that she began in Dublin in April 2012. Was it love at first sight for her with Ciaran? No, actually, it was more like pity: “The first time I saw him, I pitied him terribly,” the novel opens. “I stood in that gallery and felt not only sexual attraction (which I was aware of, dimly, as background noise) but what I can only describe as grave and troubling pity.” That doesn’t bode well now, does it?

Ciaran is an insecure, hot-tempered magazine writer. He’s also still half in love with his ex-girlfriend, Freja, whom he left behind in Copenhagen, and our narrator (an underemployed would-be writer) feels she has to fight for his attention and affections. She has body issues and drinks too much, but she’s addicted to love, and sex specifically, as much as to alcohol.

A central on-again, off-again relationship is hardly a new subject for fiction, but I admired Nolan’s work for its sharp insights into the psyche of an emotionally fragile young woman whose frantic search for someone to value her leads her into masochistic behaviours. Brief looks back at the events of 2012–14 from a present storyline set in Athens in 2019 create helpful hindsight yet reveal how much she still struggles to affirm her self-worth.

The short chapters are like freeze-frames, concentrated bursts of passion that will resonate even if the characters’ specific situations do not. And it’s not all despair and damage; there are beautiful moments here, too, like the sweet habit they had of buying an apple each and then just walking around town for a cheap outing – the source of the cover image. I marked passage after passage, but will share just a couple:

How impoverished my internal life had become, the scrabbling for a token of love from somebody who didn’t want to offer it.

I was taking away his ability to live without me easily. I subbed his rent, I cooked his food, I cleaned his clothes, so that one day soon there would come a time when he could no longer remember how he had ever done without me, and could not imagine doing so ever again.

Even if you’re burnt out on what pace amore libri blogger Rachel dubs “disaster woman” books, make an exception for this potent story of self-sabotage and -recovery. Especially if you’re a fan of Emma Jane Unsworth, The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts, and, yes, Sally Rooney. (Also reviewed by Annabel.)

My rating:

With thanks to FMcM Associates and Jonathan Cape for the free copy for review.

The rest of the shortlist:

After about 50 pages I DNFed Here Comes the Miracle by Anna Beecher, which had MA-course writing-by-numbers and seemed to be building towards When God Was a Rabbit mawkishness (how on earth did it get shortlisted?!).

See my mini reviews of the other three nominees here.

I am still rooting for Cal Flyn to win for her excellent and perennially relevant travel book, Islands of Abandonment.

Tonight there’s a shortlist readings event taking place in London. If anyone goes, do share photos! The award will be given tomorrow, the 24th. I’ll look out for the announcement.

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later.

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later. Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest.

Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest. But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs.

But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs. Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.