#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

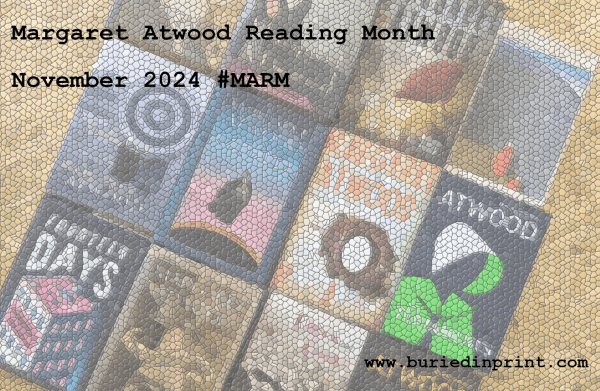

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

Interlunar (1984)

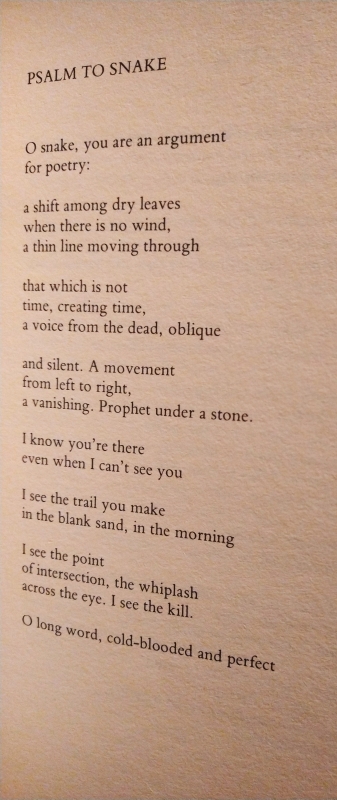

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

Truth Is Stranger than Fiction: The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen

“The island exerted a mesmeric pull. She had felt the magic of it all her life, but it was a magic that stayed on the island. You couldn’t take it with you.”

~MILD SPOILERS IN THIS ONE~

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

Now it’s just Letitia and the three children. Georgie is awaiting exam results and university offers. Jamie is the youngest and has an earnest, innocent, literal mind (I believe I first came across the novel in connection to my interest in depictions of autism, and I assume he is meant to be on the spectrum). Alba, smack in the middle, acts out via snarky comments as well as shoplifting and tormenting her brother. The locals look out for each of the family members and make allowances for the strange things they do because of grief.

In the meantime, there’s an escaped grizzly bear on the loose in the islands. The chapters rotate through the main characters’ perspectives and include short imaginings of the bear’s journey. I found it hard to take these seriously – could an animal really be in awe of the Northern Lights? – especially when Pollen begins to suggest telepathic communication occurring between Jamie and the bear.

I was a third of the way into the novel before I learned that the bear subplot was based on a true story – my husband saw a sidebar about it in the guidebook. I’d had no idea! Hercules the trained bear starred in films and commercials. In 1980, while filming an ad for Andrex, he slipped his rope and remained on the run for several weeks despite a military search, straying 20 miles and losing half his body weight before he was tranquillized and returned to his owner. We made the pilgrimage to his burial site in Langass Woodland.

Pollen herself spent childhood summers in the Outer Hebrides and remembered the buzz about the hunt for Hercules. This plus the recent death of their father makes it a pivotal summer for all three children. Though in general I appreciated the descriptions of the island, and liked the character interactions and Jamie’s guilelessness and gumption, I felt uncomfortable with his portrayal. I didn’t think it realistic for an 11-year-old to not understand the fact of death; it seemed almost offensive to suggest that, because he’s on the autism spectrum, he wouldn’t understand euphemisms about loss. The sequence where he goes looking for “Heaven” is pretty excruciating.

Add that to the unlikelihood of Jamie’s participation in the bear’s discovery and an unnecessary conspiracy element about Nicky’s death and this novel didn’t live up to its potential for me. I’d read one other book by Pollen, the memoir Meet Me in the In-Between, but won’t venture further into her work. Still, this was an interesting curio. (Public library)

[I thought about including this (and Sarah Moss’s Night Waking) in my flora-themed 20 Books of Summer because of the author’s surname, but I think I’ll make my 20 without stretching that far!]

Book Serendipity, May to June 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20‒30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Sufjan Stevens songs are mentioned in What Is a Dog? by Chloe Shaw and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- There’s a character with two different coloured eyes in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and Painting Time by Maylis de Kerangal.

- A description of a bathroom full of moisturizers and other ladylike products in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and The Interior Silence by Sarah Sands.

- A description of having to saw a piece of furniture in half to get it in or out of a room in A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- The main character is named Esther Greenwood in the Charlotte Perkins Gilman short story “The Unnatural Mother” in the anthology Close Company and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Indeed, it seems Plath may have taken her protagonist’s name from the 1916 story. What a find!

- Reading two memoirs of being in a coma for weeks and on a ventilator, with a letter or letters written by the hospital staff: Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- Reading two memoirs that mention being in hospital in Brighton: Coma by Zara Slattery and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Reading two books with a character named Tam(b)lyn: My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- A character says that they don’t miss a person who’s died so much as they miss the chance to have gotten to know them in Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour and In by Will McPhail.

- A man finds used condoms among his late father’s things in The Invention of Solitude by Paul Auster and Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour.

- An absent husband named David in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Ruby by Ann Hood.

- The murder of Thomas à Becket featured in Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot (read in April) and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall (read in June).

- Adrienne Rich is quoted in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall.

- A brother named Danny in Immediate Family by Ashley Nelson Levy and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- The male lead is a carpenter in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- An overbearing, argumentative mother who is a notably bad driver in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott.

- That dumb 1989 movie Look Who’s Talking is mentioned in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny.

- In the same evening, I started two novels that open in 1983, the year of my birth: The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris and Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid.

- “Autistic” is used as an unfortunate metaphor for uncontrollable or fearful behavior in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott (from 2000 and 2002, so they’re dated references rather than mean-spirited ones).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

- The panopticon and Foucault are referred to in Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead and I Live a Life Like Yours by Jan Grue. Specifically, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon is the one mentioned in the Shipstead, and Bentham appears in The Cape Doctor by E.J. Levy.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Two Novels of Ambivalent Parenthood: The Push & A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself

These 2021 releases I read from the library stood out to me for daring to suggest that sometimes children aren’t little angels and parenthood isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

The Push by Ashley Audrain

“Do you wish you weren’t a mother?”

“Sometimes I wish I were a different kind of person.”

A cracking psychological thriller with an unreliable narrator, this is in the same vein as The Woman in the Window, Gone Girl, and A Good Enough Mother. I hardly ever pick up novels that fit into this genre, but these were all well worth making an exception for. The Push feels closer to literary fiction than to crime. Blythe Connor, living alone with her memories, ponders what went wrong with her seemingly perfect family: a handsome architect husband, Fox, and their daughter Violet and baby son Sam. Now reduced to being a stalker and an impersonator, Blythe vows to write everything down as evidence, taking care to note when she first had cause to question whether Violet was normal. A daddy’s girl from the start, Violet never bonded with Blythe and admitted to deliberately hurting other children in her preschool. But how much of what happened next was because of Violet’s nature, and how much was Blythe’s fault for failing to be the mother the girl needed?

A cracking psychological thriller with an unreliable narrator, this is in the same vein as The Woman in the Window, Gone Girl, and A Good Enough Mother. I hardly ever pick up novels that fit into this genre, but these were all well worth making an exception for. The Push feels closer to literary fiction than to crime. Blythe Connor, living alone with her memories, ponders what went wrong with her seemingly perfect family: a handsome architect husband, Fox, and their daughter Violet and baby son Sam. Now reduced to being a stalker and an impersonator, Blythe vows to write everything down as evidence, taking care to note when she first had cause to question whether Violet was normal. A daddy’s girl from the start, Violet never bonded with Blythe and admitted to deliberately hurting other children in her preschool. But how much of what happened next was because of Violet’s nature, and how much was Blythe’s fault for failing to be the mother the girl needed?

The inkblot design of the cover cleverly evokes classical psychological concepts and experiments. A key topic the novel explores is how trauma is passed down through the generations: Blythe had worried that she wasn’t cut out for motherhood, chiefly because her mother and her grandmother both abandoned their daughters. “Blythe, the women in this family, we’re different. You’ll see,” her mother had warned. The exchange between Blythe and her mother that opens my review reiterates her suspicion: some people just aren’t cut out for parenting. Blythe can’t dismiss her daughter as evil because she knows how much guilt rests on her own shoulders, and because she doubts that she saw what she thought she saw. Moreover, the fact that her experience with Sam was completely different makes her feel ambivalent about motherhood: she’s seen how wonderful it can be, but also how it can turn bad. The nuance sets the book apart from run-of-the-mill thrillers. Yet it’s in short, page-turning chapters, so it reads very quickly and would make a great book club selection.

My rating:

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

At its best, autofiction is an intriguing blend of memoir and fiction, all of it true and universal in appeal. Davies’ minimalist approach – short sections skating over the months and years, wryly pulling out representative moments here and there, all in a mere 180 pages – could hardly be more different from Karl Ove Knausgaard’s, but both are equally dedicated to the unique alchemy of crystallizing fatherhood by illuminating its daily heartaches and joys.

Years ago, “the writer” and his wife were presented with a choice. When genetic tests indicated mosaicism, they terminated their first pregnancy. Instead of a little girl, they later had a baby boy who presented his own challenges, including delayed development and possible ASD. Years later, the abortion still haunts “the father.” He attempts to exorcise his shame (the title = how Anaïs Nin defined it) by volunteering at an abortion clinic. Escorting patients to and from their cars, ignoring the taunts of protestors, he lives out his conviction that you can never fully know what others are going through and why they make the decisions they do.

Years ago, “the writer” and his wife were presented with a choice. When genetic tests indicated mosaicism, they terminated their first pregnancy. Instead of a little girl, they later had a baby boy who presented his own challenges, including delayed development and possible ASD. Years later, the abortion still haunts “the father.” He attempts to exorcise his shame (the title = how Anaïs Nin defined it) by volunteering at an abortion clinic. Escorting patients to and from their cars, ignoring the taunts of protestors, he lives out his conviction that you can never fully know what others are going through and why they make the decisions they do.

Davies gets the tone just right in this novella, showing both sides of parenthood and voicing the things you aren’t allowed to think, or at least not to admit to – starting with abortion, which would-be fathers aren’t expected to have strong feelings about. Soon after the writer’s son is born: “He feels about himself for love, the way he might pat his pockets for his wallet and keys. Do I love him yet? Is this love?” As the boy grows into a figure of pathos: “All the things they’ve imagined him growing up to be: A basketball player, a fireman, a chef. [vs. what he actually seems to be] Allergic, friendless, autistic.” Davies also has a gift for zinging phrases, like “the deification of babies” and “the baby-industrial complex” of Babies R Us.

But what I most loved was the rumination on the role that chance plays in a life. “All the coin flips. All the what ifs. Like the litany of prompts he uses in writing class. Heads and tales.” The writer has a background in physics (as Davies himself does), so often brings up Schrödinger’s cat as a metaphor – in any situation, things might have gone either way. Now that the possibilities have narrowed to one and the path has been started, what will you do? The treatment of luck, in particular, led me to think of this as a cross between Larry’s Party by Carol Shields and What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez. The style is similar to Jenny Offill’s; another similar and nearly contemporaneous release is Brood by Jackie Polzin.

I know I read The Fortunes back in 2016 but I retain virtually no memory of it. Davies’s prose, themes, and voice stood out much more for me here. I’ll try his novel The Welsh Girl, too, maybe even for book club later this year. This is an early entry on my Best of 2021 list.

Favorite lines:

“this is also what the internet is for, he thinks. If online porn universalizes shame, social media universalizes judgment. Both exercises in self-gratification.”

“An older colleague told him once cats were baby substitutes. ‘They weigh the same, they sleep on you, they roll around on their backs kicking their legs in the air. They mewl.’”

For more on abortion from a male perspective: The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Ars Botanica by Tim Taranto.

My rating:

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed  “My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,  I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,  Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on  Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in