The Story Girl by L. M. Montgomery (1911) #ReadingStoryGirl

Six months after the Jane of Lantern Hill readalong, Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah Emsley have chosen an earlier work by Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Story Girl, and its sequel The Golden Road, for November buddy reading.

The book opens one May as brothers Felix and Beverley King are sent from Toronto to Prince Edward Island to stay with an aunt and uncle while their father is away on business. Beverley tells us about their thrilling six months of running half-wild with their cousins Cecily, Dan, Felicity, and Sara Stanley – better known by her nickname of the Story Girl, also to differentiate her from another Sara – and the hired boy, Peter. This line gives a sense of the group’s dynamic: “Felicity to look at—the Story Girl to tell us tales of wonder—Cecily to admire us—Dan and Peter to play with—what more could reasonable fellows want?”

Felicity is pretty and domestically inclined; Sara knows it would be better to be useful like Felicity, but all she has is her storytelling ability. Some are fantasy (“The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess”); some are local tales that have passed into folk memory (“How Betty Sherman Won a Husband”). Beverley is in raptures over the Story Girl’s orations: “if voices had colour, hers would have been like a rainbow. It made words live. … we had listened entranced. I have written down the bare words of the story, as she told it; but I can never reproduce the charm and colour and spirit she infused into it. It lived for us.”

The cousins’ adventures are gently amusing and quite tame. They all write down their dreams in notebooks. Peter debates which church denomination to join and the boys engage in a sermon competition. Pat the cat has to be rescued from bewitching, and receives a dose of medicine in lard he licks off his paws and fur. The Story Girl makes a pudding with sawdust instead of cornmeal (reminding me of Anne Shirley and the dead mouse in the plum pudding). Life consistently teaches lessons in humility, as when they are all duped by Billy Robinson and his magic seeds, which he says will change whatever each one most resents – straight hair, plumpness, height; and there is a false alarm about the end of the world.

I found the novel fairly twee and realized at a certain point that I was skimming over more than I was reading. As was my complaint about Jane of Lantern Hill, there is a predictable near-death illness towards the end. The descriptions of Felicity and the Story Girl are purple (“when the Story Girl wreathed her nut-brown tresses with crimson leaves it seemed, as Peter said, that they grow on her—as if the gold and flame of her spirit had broken out in a coronal”); I had to remind myself that this reflects on Beverley more so than on Montgomery. From Naomi’s review of The Golden Road, I think that would be more to my taste because it has a clear plot rather than just stringing together pleasant but mostly forgettable anecdotes.

Still, it’s been fun to discover some of L. M. Montgomery’s lesser-known work, and there are sweet words about cats and the seasons:

“I am very good friends with all cats. They are so sleek and comfortable and dignified. And it is so easy to make them happy.”

“The beauty of winter is that it makes you appreciate spring.”

This effectively captures the long, magical summer days of childhood. I thought about when I was a kid and loved trips up to my mother’s hometown in upstate New York, where her brothers still lived. I was in awe of the Judd cousins’ big house, acres of lawn and untold luxuries such as Nintendo and a swimming pool. I guess I was as star-struck as Beverley. (University library)

#1962Club: A Dozen Books I’d Read Before

I totally failed to read a new-to-me 1962 publication this year. I’m disappointed in myself as I usually manage to contribute one or two reviews to each of Karen and Simon’s year clubs, and it’s always a good excuse to read some classics.

My mistake this time was to only get one option: Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, which I had my husband borrow for me from the university library. I opened it up and couldn’t make head or tail of it. I’m sure it’s very clever and meta, and I’ve enjoyed Nabokov before (Pnin, in particular), but I clearly needed to be in the right frame of mind for a challenge, and this month I was not.

Looking through the Goodreads list of the top 100 books from 1962, and spying on others’ contributions to the week, though, I can see that it was a great year for literature (aren’t they all?). Here are 12 books from 1962 that I happen to have read before, most of which I’ve reviewed here in the past few years. I’ve linked to those and/or given review excerpts where I have them, and the rest I describe to the best of my muzzy memory.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats – A perennial favourite from my childhood, with a paper-collage style that has influenced many illustrators. Just looking at the cover makes me nostalgic for the sort of wintry American mornings when I’d open an eye to a curiously bright aura from around the window, glance at the clock and realize my mom had turned off my alarm because it was a snow day and I’d have nothing ahead of me apart from sledding, playing boardgames and drinking hot cocoa with my best friend. There was no better feeling.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

Here’s hoping I make a better effort at the next year club!

Happy Birthday & Bookshop Day

Happy Bookshop Day from Hay-on-Wye (and its newest bookshop, Gay on Wye)!

Today is my 40th birthday and I have been spending the weekend book shopping, reading, eating and drinking. What more could I ask for?

Before we left for Wales, I had my book club over for birthday cakes and bubbles. My husband made me a chocolate Guinness cake (vegan so everyone could share it) and pumpkin chai cupcakes; both recipes were from Hummingbird Bakery cookbooks.

I’ll report back on Monday with my book haul and trip highlights.

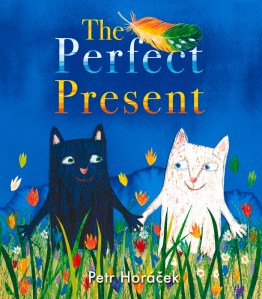

For now, here are some sweet lines from a children’s book I read this morning, about cats named Tom and Mot who discover that friendship and imagination are the greatest gifts, and that present has a double meaning: the now that must be appreciated.

“And then it was time for a hot drink and the cake. The cake tasted like the BEST birthday cake in the world. … ‘Today was the best present in the world,’ said Tom. ‘The perfect present!’”

Love Your Library & Miscellaneous News, July 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her faithful participation (her post is here).

Today happens to be my 10th freelancing anniversary. I’m not much in the mood for celebrating as my career feels like it’s at a low ebb just now. However, I’m trying to be proactive: I contacted all my existing employers asking about the possibility of more work and a few opportunities are forthcoming. Plus I have a new paid review venue in the pipeline.

Tomorrow the Booker Prize longlist will be announced. I haven’t had a whole lot of time to think about it, but over the past few months I did keep a running list of novels I thought would be eligible, so here are 13 (a “Booker dozen”) that I think might be strong possibilities:

Old God’s Time, Sebastian Barry

The New Life, Tom Crewe

Fire Rush, Jacqueline Crooks

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Enter Ghost, Isabella Hammad

Hungry Ghosts, Kevin Jared Hosein

August Blue, Deborah Levy

The Sun Walks Down, Fiona McFarlane

Cuddy, Benjamin Myers

Shy, Max Porter

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C Pam Zhang

See also Clare’s and Susan’s predictions. All three of us coincide on one of these titles!

Back to the library content!

I appreciated this mini-speech by Bob Comet, the introverted librarian protagonist of Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist, about why he loves libraries … but not people so much:

“I like the way I feel when I’m there. It’s a place that makes sense to me. I like that anyone can come in and get the books they want for free. The people bring the books home and take care of them, then bring them back so that other people can do the same. … I like the idea of people.”

I recently added a new regular task to my library volunteering roster: choosing a selection of the month’s new stock (30 fiction releases and 9 fiction) and adding them to a PDF template with the cover, title and author, and a blurb from the library catalogue or Goodreads, etc. The sheets are printed out at each branch library and displayed in a binder for patrons to browse. I was so proud to see my pages in there! There are three of us alternating this task, so I’ll be doing it four times a year. My next month is October.

On my Scotland travels last month, I took photos of two cute little libraries, one in Wigtown (L) and the other in Tarbert.

I’m currently on holiday again, with university friends in the Lake District for a week (Wild Fell, below, is for reading in advance of a trip to, and on location in, Haweswater), and you can be sure I brought plenty of library books along with me.

My reading and borrowing since last time:

READ

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

- Sunburn by Andi Watson

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang (for book club)

+ 3 children’s picture books from the Wainwright Prize longlist:

- Blobfish by Olaf Falafel: Silly and with the merest scrape of an environmentalist message pasted on (the fish temporarily gets stuck in a plastic bag).

- The Zebra’s Great Escape by Katherine Rundell: Loved this super-cute, cheeky story of a little girl whose understanding of animal language allows her to become part of a natural network rescuing a menagerie held captive by an evil collector.

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher by Anna Wilson: Nice drawings and attention to nature and its seasonality, but rather mawkish. (Adult birds don’t die off annually!)

SKIMMED

- A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again by Joanna Biggs – The backstory is Biggs getting divorced in her thirties and moving to NYC. Her eight chosen female authors are VERY familiar, barring, perhaps, Zora Neale Hurston (thank goodness she chose two Black authors, as so many group biographies are all about white women). Do we need potted biographies of such well-known figures? Probably not. Nonetheless, it was clever how she wove her own story and reactions to their works into the biographical material, and the writing is so strong I could excuse any retreading of ground.

CURRENTLY READING

- One Midsummer’s Day by Mark Cocker

- King by Jonathan Eig

- Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries by Heather Fawcett

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Wild Fell by Lee Schofield

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

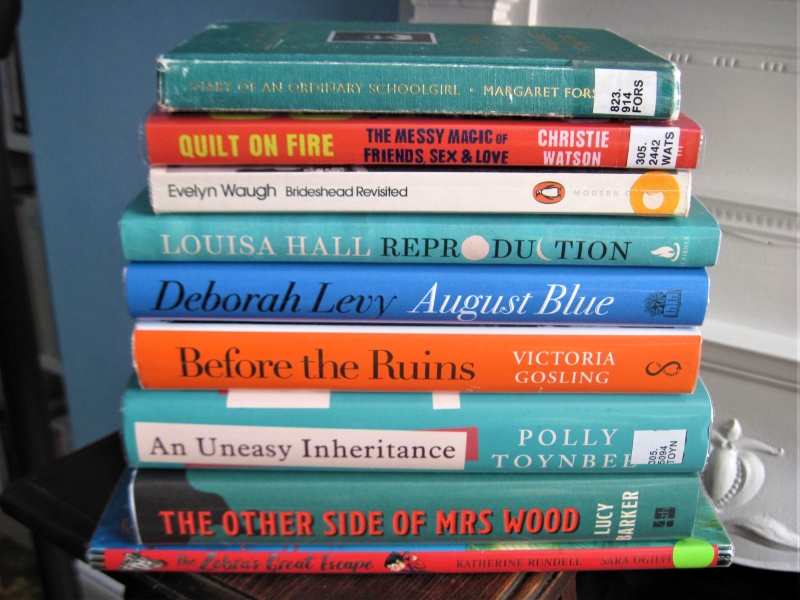

Lots of lovely teal in this latest batch.

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Undercurrent by Natasha Carthew – This was requested after me. I read 21% and will either pick it up on my Kindle via the NetGalley book or get it out another time.

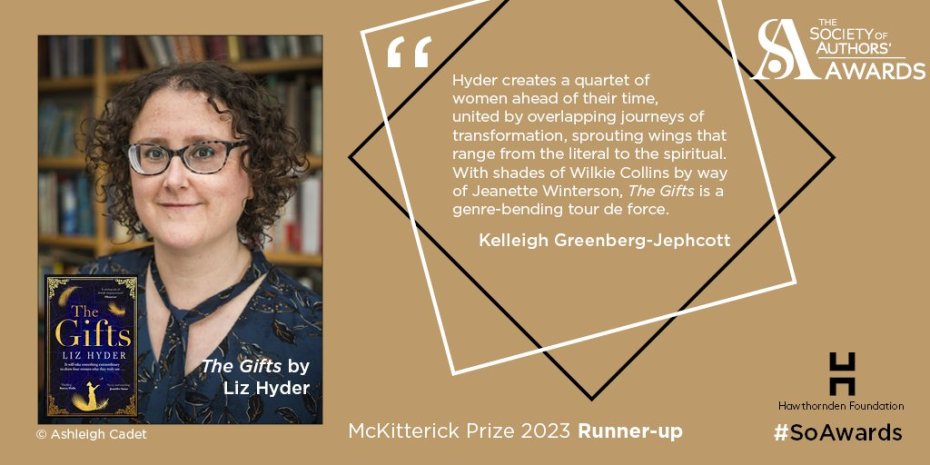

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder – I’ll try this another time when I can give it more attention.

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson – I loved The Ninth Child, but have DNFed her other two novels, alas! I even got to page 122 in this, but I had little interest in seeing how the storylines fit together.

- The Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers – I’m awful about trying mystery series, usually DNFing or giving up after the first book. I just can’t care whodunnit.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Prize Updates: McKitterick Prize Winner and Wainwright Prize Longlists

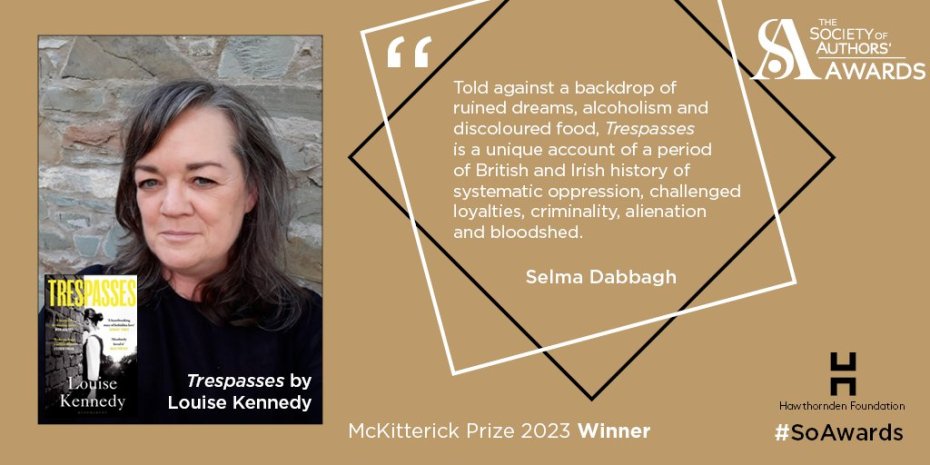

It was my second year as a first-round manuscript judge for the McKitterick Prize; have a look at my rundown of the shortlist here.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

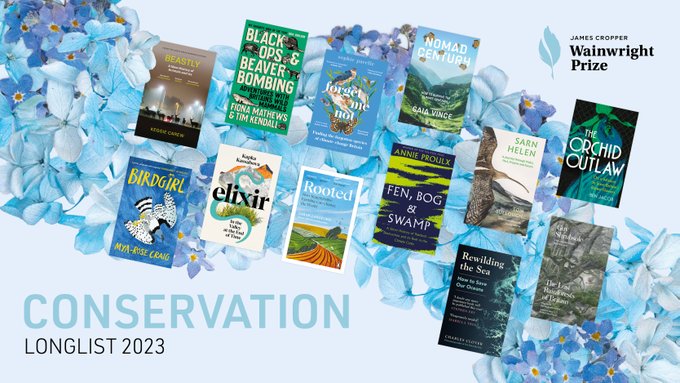

I’m a big fan of the Wainwright Prize for nature and conservation writing, and have been following it particularly closely since 2020, when I happened to read most of the nominees. In 2021 I also managed to read quite a lot from the longlists; 2022, the first year of an additional prize for children’s literature, saw me reading about a third of the total nominees.

This is the third year that I’ve been part of an “academy” of bloggers, booksellers, former judges and previously shortlisted authors asked to comment on a very long list of publisher submissions. I’m delighted that a few of my preferences made it through to the longlists.

My taste generally runs more to the narrative nature writing than the popular science or travel-based books. I find I’ve read just two from the Nature list (Bersweden and Huband) and one each from Conservation (Pavelle) and Children’s (Hargrave) so far.

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing longlist:

- The Swimmer: The Wild Life of Roger Deakin, Patrick Barkham (Hamish Hamilton)

- The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness, Amy-Jane Beer (Bloomsbury)

- Where the Wildflowers Grow, Leif Bersweden (Hodder)

- Twelve Words for Moss, Elizabeth-Jane Burnett (Allen Lane)

- Cacophony of Bone, Kerri ní Dochartaigh (Canongate)

- Sea Bean, Sally Huband (Hutchinson)

- Ten Birds that Changed the World, Stephen Moss (Faber)

- A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast, Dorthe Nors, translated by Caroline Waight (Pushkin)

- The Golden Mole: And Other Living Treasure, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Talya Baldwin (Faber)

- Belonging: Natural Histories of Place, Identity and Home, Amanda Thomson (Canongate)

- Why Women Grow: Stories of Soil, Sisterhood and Survival, Alice Vincent (Canongate)

- Landlines, Raynor Winn (Penguin)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Writing on Conservation longlist:

- Sarn Helen: A Journey Through Wales, Past, Present and Future, Tom Bullough, illustrated by Jackie Morris (Granta)

- Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us, Keggie Carew (Canongate)

- Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans, Charles Clover (Ebury)

- Birdgirl, Mya-Rose Craig (Jonathan Cape)

- The Orchid Outlaw, Ben Jacob (John Murray)

- Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, Kapka Kassabova (Jonathan Cape)

- Rooted: How Regenerative Farming Can Change the World, Sarah Langford (Viking)

- Black Ops and Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals, Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall (Oneworld)

- Forget Me Not, Sophie Pavelle (Bloomsbury)

- Fen, Bog, and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and its Role in the Climate Crisis, Annie Proulx (Fourth Estate)

- The Lost Rainforests of Britain, Guy Shrubsole (HarperCollins)

- Nomad Century: How to Survive the Climate Upheaval, Gaia Vince (Allen Lane)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Children’s Writing on Nature and Conservation longlist:

- The Earth Book, Hannah Alice (Nosy Crow)

- The Light in Everything, Katya Balen, illustrated by Sydney Smith (Bloomsbury)

- Billy Conker’s Nature-Spotting Adventure, Conor Busuttil (O’Brien)

- Protecting the Planet: The Season of Giraffes, Nicola Davies, illustrated by Emily Sutton (Walker)

- Blobfish, Olaf Falafel (Walker)

- A Friend to Nature, Laura Knowles, illustrated by Rebecca Gibbon (Welbeck)

- Spark, M G Leonard (Walker)

- A Wild Child’s Book of Birds, Dara McAnulty (Macmillan)

- Leila and the Blue Fox, Kiran Millwood Hargrave, illustrated by Tom de Freston (Hachette Children’s Group)

- The Zebra’s Great Escape, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Sara Ogilvie (Bloomsbury)

- Archie’s Apple, Hannah Shuckburgh, illustrated by Octavia Mackenzie (Little Toller)

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher, Anna Wilson, illustrated by Sarah Massini (Nosy Crow)

It’s impressive that women writers are represented so well this year: 9/12 for Nature, 8/12 for Conservation, and 8/12 for Children’s. Amusingly, Katherine Rundell is on TWO of the lists. There are also, refreshingly, several BIPOC authors, and – I think for the first time ever – a work in translation (A Line in the World by Dorthe Nors, which I have as a set-aside proof copy and will get back into at once).

Here is where I have to admit that quite a number of the nominees, overall, are books I DNFed, authors whose work I’ve tried before and not enjoyed, or books I’ve been turned off of by the reviews. I’ll not mention these by name just now, and will leave any predictions for a future date when I’ve read a few more of the nominees. It seems that I’m most likely to catch up with the majority of the children’s longlist, if anything.

The shortlists will be announced on 10 August, and winners will be announced on 14 September at a 10th Anniversary live event held as part of the Kendal Mountain Festival in Cumbria (tickets available here).

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see shortlisted?

Three on a Theme: Frost Fairs Books

Here in southern England, we’ve just had a couple of weeks of hard frost. The local canal froze over for a time; the other day when I thought it had all thawed, a pair of mallard ducks surprised me by appearing to walk on water. In previous centuries, the entire Thames has been known to freeze through central London. (I’d like to revisit Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for a 17th-century scene of that.) This thematic trio of a children’s book, a historical novel, and a poetry collection came together rather by accident: I already had the poetry collection on my shelf, then saw frost fairs referenced in the blurb of the novel, and later spotted the third book while shelving in the children’s section of the library.

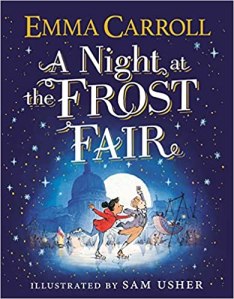

A Night at the Frost Fair by Emma Carroll (2021)

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

A sickly little boy named Eddie is her tour guide to the games, rides and snacks on offer here in 1788, but there’s a man around who wants to keep him from enjoying the fair. Maya hopes to help Eddie, and Gran, all while figuring out what the gift parcel means. A low page count meant this felt pretty thin, with everything wrapped up too soon. The problem, really, was that – believe it or not – this isn’t the first middle-grade time-slip historical fantasy novel about frost fairs that I’ve read; the other, Frost by Holly Webb, was better. Sam Usher’s Quentin Blake-like illustrations are a bonus, though. (Public library) ![]()

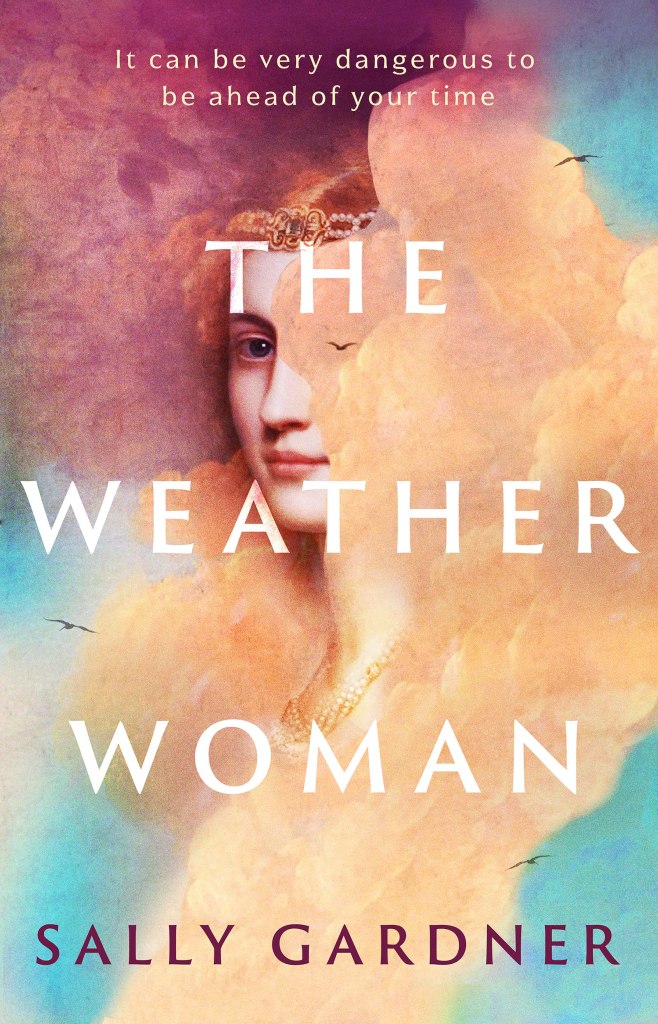

The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (2022)

This has been catalogued as science fiction by my library system, but I’d be more likely to describe it as historical fiction with a touch of magic realism, similar to The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock or Things in Jars. I loved the way the action is bookended by the frost fairs of 1789 and 1814. There’s a whiff of the fairy tale in the setup: when we meet Neva, she’s a little girl whose parents operate one of the fair’s attractions, a chess-playing bear. She knows, like no one else seems to, that the ice is shifting and it’s not safe to stay by the Thames. When the predicted tragedy comes, she’s left an orphan and adopted by Victor Friezland, a clockmaker who shares her Russian heritage. He lives in a wonderfully peculiar house made out of ship parts and, between him, Neva, the housekeeper Elise, and other servants, friends and neighbours, they form a delightful makeshift family.

Neva predicts the weather faultlessly, even years ahead. It’s somewhere between synaesthetic and mystical, this ability to hear the ice speaking and see what the clouds hold. While others in their London circle engage in early meteorological prediction, her talent is different. Victor decides to harness it as an attraction, developing “The Weather Woman” as first an automaton and then a magic lantern show, both with Neva behind the scenes giving unerring forecasts. At the same time, Neva brings her childhood imaginary friend to life, dressing in men’s clothing and appearing as Victor’s business partner, Eugene Jonas, in public.

These various disguises are presented as the only way that a woman could be taken seriously in the early 19th century. Gardner is careful to note that Neva does not believe she is, or seek to become, a man; “She thinks she’s been born into the wrong time, not necessarily the wrong sex. As for her mind, that belongs to a different world altogether.” (Whereas there is a trans character and a couple of queer ones; it would also have been interesting for Gardner to take further the male lead’s attraction to Eugene Jonas.) From her early teens on, she’s declared that she doesn’t intend to marry or have children, but in what I suspect is a trope of romance fiction, she changes her tune when she meets the right man. This was slightly disappointing, yet just one of several satisfying matches made over the course of this rollicking story.

London charms here despite its Dickensian (avant la lettre) grime – mudlarks and body snatchers, gambling and trickery, gloomy pubs and shipwrecks, weaselly lawyers and high-society soirees. The plot moves quickly and holds a lot of surprises and diverting secondary characters. While the novel could have done with some trimming – something I’d probably say about the majority of 450-pagers – I remained hooked and found it fun and racy. You’ll want to stick around for a terrific late set-piece on the ice. Gardner had a career in theatre costume design before writing children’s books. I’ll also try her teen novel, I, Coriander. (Public library) ![]()

[Two potential anachronisms: “Hold your horses” (p. 202) and calling someone “a card” (p. 209) – both slang uses that more likely date from the 1830s or 1840s.]

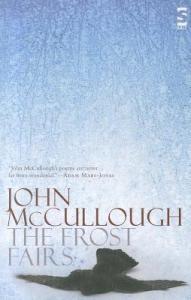

The Frost Fairs by John McCullough (2010)

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

Overnight the Thames begins to move again.

The ice beneath the frost fair cracks. Tents,

merry-go-rounds and bookstalls glide about

On islands given up for lost. They race,

switch places, touch—the printing press nuzzling

the swings—then part, slip quietly under.

I also liked the wordplay of “The Dictionary Man,” the alliteration and English summer setting of “Miss Fothergill Observes a Snail,” and the sibilance versus jarringly violent imagery of “Severance.” However, it was hard to detect links that would create overall cohesion in the book. (Purchased directly from Salt Publishing) ![]()

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession.

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession.

Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)

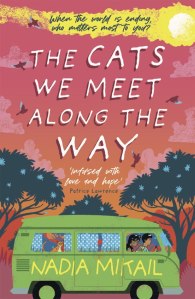

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children.

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children. My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of

My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of  My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress.

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress. Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of

Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of  The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.

The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.  A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.

A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.  Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.

Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.  The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.

The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.  Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.

Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.  Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.

Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.  Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.

Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.  The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.  The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit. A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one.

A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one. Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his.

Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his. Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling.

Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling. Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement. Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.

Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.