Last Love Your Library of 2025 & Another for #DoorstoppersInDecember

Thanks to Eleanor, Margaret and Skai for writing about their recent library reading! Marcie also joined in with a post about completing Toronto Public Library’s 2025 Reading Challenge with books by Indigenous authors.

I managed to fit in a few more 2025 releases before Christmas. My plan for January is to focus on reading from my own shelves (which includes McKitterick Prize submissions and perhaps also review copies to catch up on), so expect next month to be a lighter one.

My recent reading has featured many mentions of how much libraries mean, particularly to young women.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

My library use over the last month:

(links are to any reviews of books not already covered on the blog)

READ

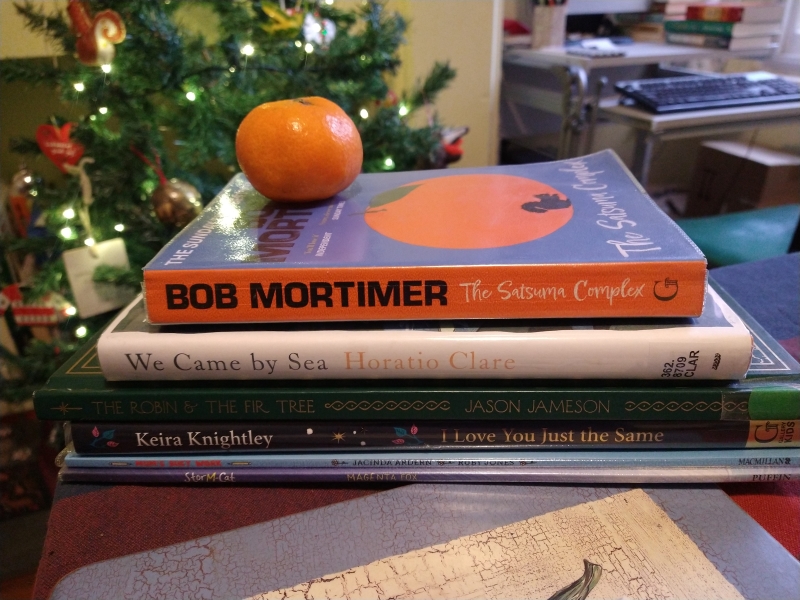

- Mum’s Busy Work by Jacinda Ardern; illus. Ruby Jones

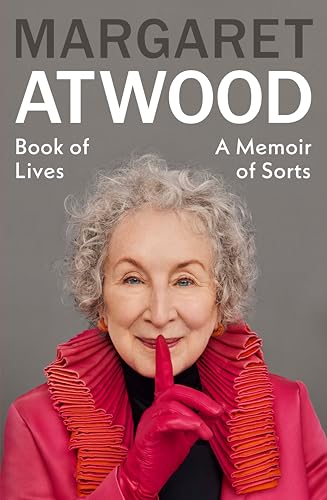

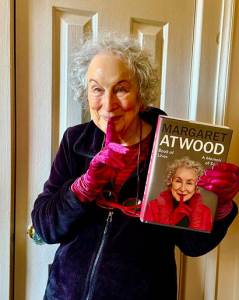

- Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

- Storm-Cat by Magenta Fox

- The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson

- I Love You Just the Same by Keira Knightley – Proof that celebrities should not be writing children’s books. I would say the story and drawings were pretty good … if she were a college student.

- Winter by Val McDermid

- The Search for the Giant Arctic Jellyfish, The Search for Carmella, & The Search for Our Cosmic Neighbours by Chloe Savage

- Weirdo Goes Wild by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird; illustrated by Magenta Fox

- Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

+ A final contribution to #DoorstoppersInDecember

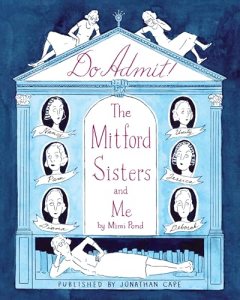

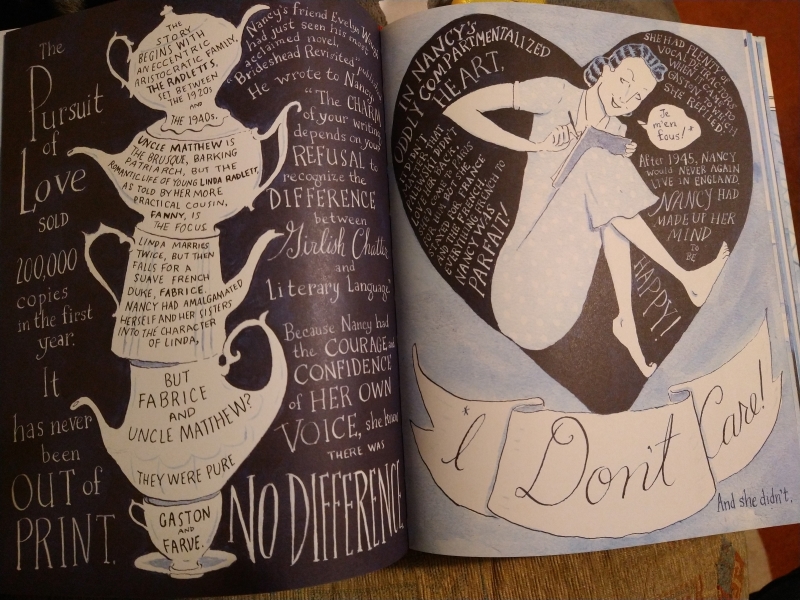

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me by Mimi Pond

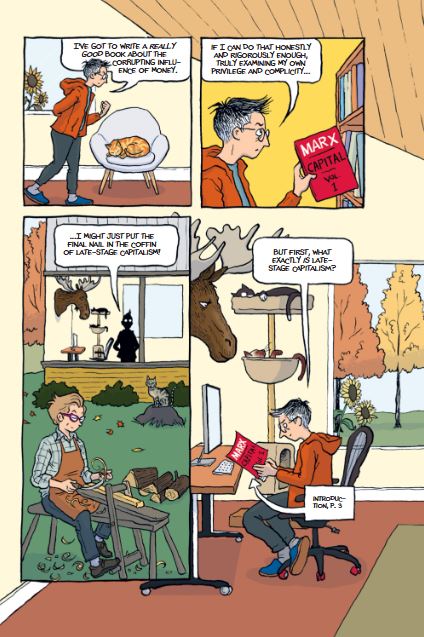

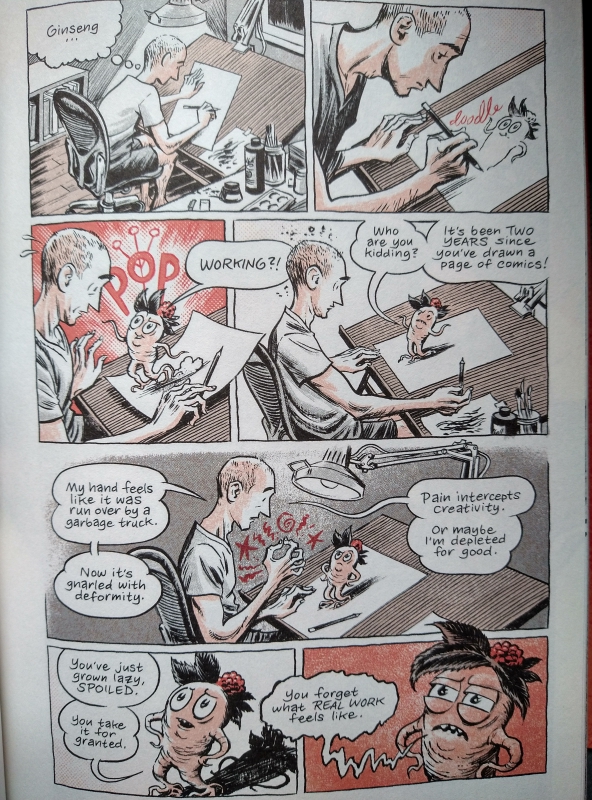

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages]

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages] ![]()

CURRENTLY READING

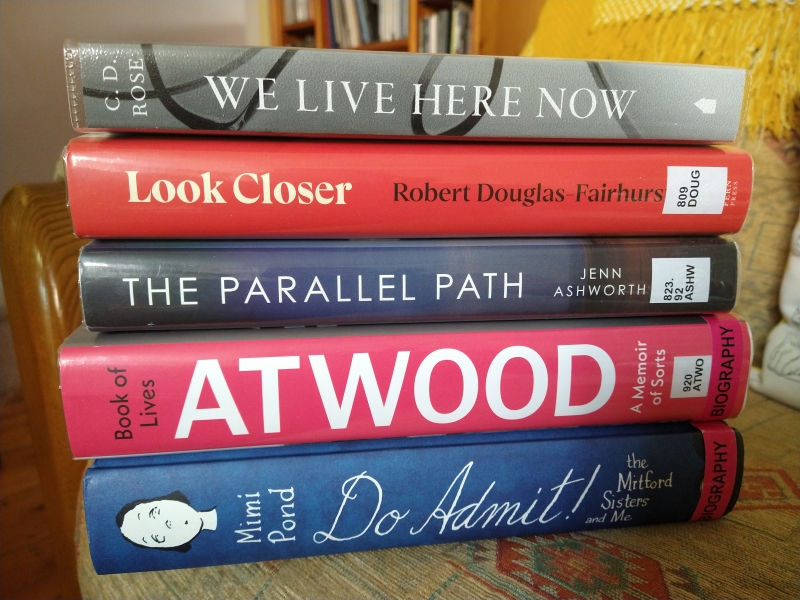

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- The Satsuma Complex by Bob Mortimer (for book club in January; I’m grumpy about it because I didn’t vote for this one, had no idea who the author [a TV comedian in the UK] was, and the writing is shaky at best)

- We Live Here Now by C.D. Rose

SKIMMED

- Look Closer: How to Get More out of Reading by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

- We Came by Sea by Horatio Clare

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith

- Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- Ultra-Processed People by Dr. Chris van Tulleken (for book club in February)

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

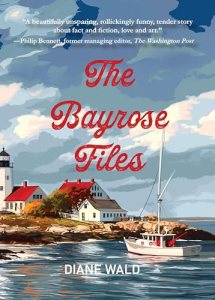

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Reading Ireland Month, Part II: Hughes, Kennedy, Murray

My second contribution to Reading Ireland Month after a first batch that included poetry and a novel.

Today I have a poetry collection based around science and travel, and two multi-award-winning novels, one set in the thick of the Troubles in Belfast and another about the crumbling of an ordinary suburban family.

Gathering Evidence by Caoilinn Hughes (2014)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher) ![]()

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (2022)

Despite its many accolades, not least a shortlisting for the Women’s Prize, I couldn’t summon much enthusiasm for reading a novel about the Troubles. I don’t know why I tend to avoid this topic; perhaps it’s the insidiousness of fighting that’s not part of a war somewhere else, but ongoing domestic terrorism instead. Combine that with an affair – Cushla is a 24-year-old schoolteacher who starts sleeping with a middle-aged, married barrister she meets in her family’s pub – and it sounded like a tired, ordinary plot. But after this won last year’s McKitterick Prize (for debut authors over 40) and I was sent the whole shortlist in thanks for being a manuscript judge, I thought I should get over myself and give it a try.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

This doesn’t read like a first novel at all, with each character fully realized and the plot so carefully constructed that I was as shocked as Cushla by a revelation four-fifths of the way through. Desire is bound up with guilt; can anyone ever be happy when violence is so ubiquitous and random? “Booby trap. Incendiary device. Gelignite. Nitroglycerine. Petrol bomb. Rubber bullets. Saracen. Internment. The Special Powers Act. Vanguard. The vocabulary of a seven-year-old child now.” But a brief framing episode set in 2015 gives hope of life beyond seemingly inescapable tragedy. (Free from the Society of Authors) ![]()

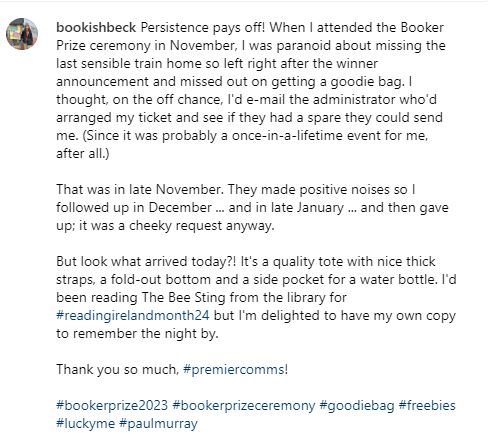

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray (2023)

“The trouble is coming from inside; from his family. And unless something happens to stop it, it will keep billowing out, worse and worse”

Another great Irish novel I nearly missed out on, despite it being shortlisted for the Booker Prize and Writers’ Prize and winning the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize, this one because I was daunted by its doorstopper proportions. I’d gotten it in mind that it was all about money: Dickie Barnes’s car dealership is foundering and the straitened circumstances affect his whole family (wife Imelda, teenage daughter Cass, adolescent son PJ). A belated post-financial crash novel? Again, it sounded tired, maybe clichéd.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

There are no speech marks throughout, and virtually no punctuation in Imelda’s sections. There are otherwise no clever tricks to distinguish the points-of-view, though. The voice is consistent. Murray doesn’t have to strain to sound like a teenage girl; he fully and convincingly inhabits each character (even some additional ones towards the end). I particularly liked the final “Age of Loneliness” section, which starts rotating between the perspectives more quickly, each one now in the second person. It all builds towards a truly thrilling yet inconclusive ending. I could imagine this as a TV miniseries for sure.

SPOILERS, if you’re worried about that sort of thing:

It was all the details I didn’t pick up from my pre-reading about The Bee Sting that made it so intricate and rewarding. Imelda’s awful upbringing in macho poverty and how it seemed that Rose, then Frank, might save her. The cruelty of Frank’s accidental death and the way that, for both Imelda and Dickie, being together seemed like the only way of getting over him, even if Imelda was marrying the ‘wrong’ brother. The recurrence of same-sex attraction for Dickie, then Cass. The irony of the bee sting that never was.

BUT. Yes, it’s too long, particularly Imelda’s central section. I had to start skimming to have any hope of making it through. Trim the whole thing by 200 pages and then we’re really talking. But I will certainly read Murray again, and most likely will revisit this book in the future to give it the attention it deserves. I read it from the library’s Bestsellers collection; the story of how I own a copy as of this week is a long one…

(Public library; free from the Booker Prize/Premier Comms) ![]()

I’ll be catching up on reviewing March releases in early April.

Happy Easter to those who celebrate!

This and That (The January Blahs)

The January blahs have well and truly arrived. The last few months of 2023 (December in particular) were too full: I had so much going on that I was always rushing from one thing to the next and worrying I didn’t have the time to adequately appreciate any of it. Now my problem is the opposite: very little to do, work or otherwise; not much on the calendar to look forward to; and the weather and house so cold I struggle to get up each morning and push past the brain fog to settle to any task. As I kept thinking to myself all autumn, there has to be a middle ground between manic busyness and boredom. That’s the head space where I’d like to be living, instead of having to choose between hibernation and having no time to myself.

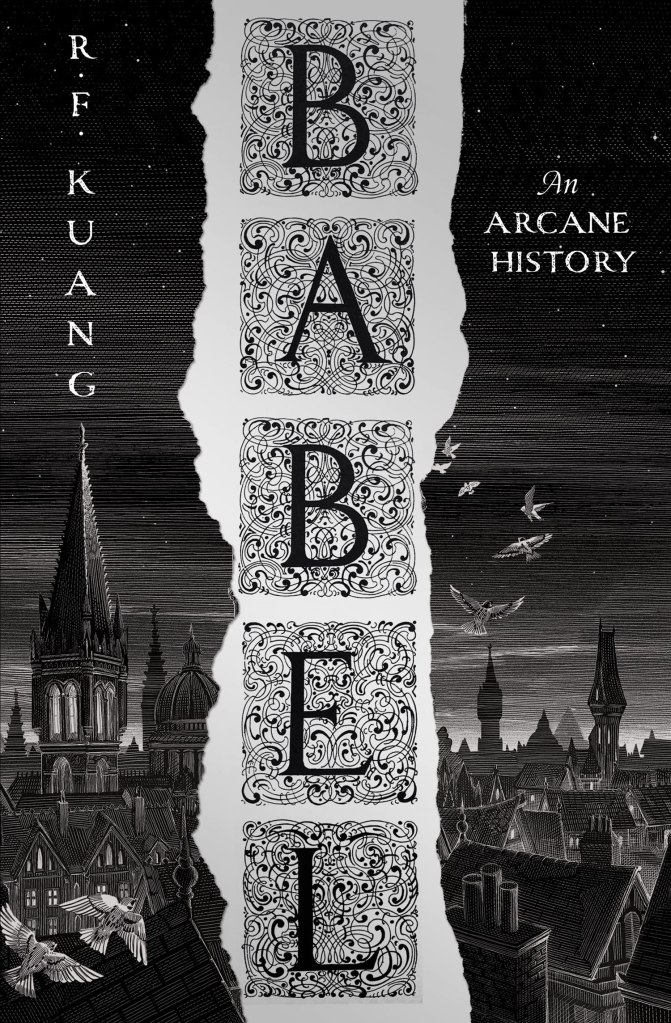

At least these frigid January days are good for being buried in books. Unusually for me, I’m in the middle of seven doorstoppers, including King by Jonathan Eig (perfect timing as Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day), Wellness by Nathan Hill, and Babel by R.F. Kuang (a nominal buddy read with my husband).

Another is Carol Shields’s Collected Short Stories for a buddy rereading project with Marcie of Buried in Print. We’re partway through the first volume, Various Miracles, after a hiccup when we realized my UK edition had a different story order and, in fact, different contents – it must have been released as a best-of. We’ll read one volume per month in January–March. I also plan to join Heaven Ali in reading at least one Margaret Drabble book this year. I have The Waterfall lined up, and her Arnold Bennett biography lurking. Meanwhile, the Read Indies challenge, hosted by Karen and Lizzy in February, will be a great excuse to catch up on some review books from independent publishers.

Literary prize season will be heating up soon. I put all of the Women’s Prize (fiction and nonfiction!) dates on my calendar and I have a running list, in a file on my desktop, of all the novels I’ve come across that would be eligible for this year’s race. I’m currently reading two memoirs from the Nero Book Awards nonfiction shortlist. Last year it looked like the Folio Prize was set to replace the Costa Awards, giving category prizes and choosing an overall winner. But then another coffee chain, Caffè Nero, came along and picked up the mantle.

This year the Folio has been rebranded as The Writers’ Prize, again with three categories, which don’t quite overlap with the Costa/Nero ones. The Writers’ Prize shortlists just came out on Tuesday. I happen to have read one of the poetry nominees (Chan) and one of the fiction (Enright). I’m going to have a go at reading the others that I can source via the library. I’ll even try The Bee Sting given it’s on both the Nero and Writers’ shortlists (ditto the Booker) and I have a newfound tolerance of doorstoppers.

As for my own literary prize involvement, my McKitterick Prize manuscript longlist is due on the 31st. I think I have it finalized. Out of 80 manuscripts, I’ve chosen 5. The first 3 stood out by a mile, but deciding on the other 2 was really tricky. We judges are meeting up online next week.

I’m listening to my second-ever audiobook, an Audible book I was sent as a birthday gift: There Plant Eyes by M. Leona Godin. My routine is to find a relatively mindless data entry task to do and put on a chapter at a time.

There are a handful of authors I follow on Substack to keep up with what they’re doing in between books: Susan Cain, Jean Hannah Edelstein, Catherine Newman, Anne Boyd Rioux, Nell Stevens (who seems to have gone dormant?), Emma Straub and Molly Wizenberg. So far I haven’t gone for the paid option on any of the subscriptions, so sometimes I don’t get to read the whole post, or can only see selected posts. But it’s still so nice to ‘hear’ these women’s voices occasionally, right in my inbox.

My current earworms are from Belle and Sebastian’s Late Developers album, which I was given for Christmas. These lyrics from the title track – saved, refreshingly, for last; it’s a great strategy to end on a peppy song (an uplifting anthem with gospel choir and horn section!) instead of tailing off – feel particularly apt:

Live inside your head

Get out of your bed

Brush the cobwebs off

I feel most awake and alive when I’m on my daily walk by the canal. It’s such a joy to hear the birdsong and see whatever is out there to be seen. The other day there was a red kite zooming up from a field and over the houses, the sun turning his tail into a burnished chestnut. And on the opposite bank, a cuboid rump that turned out to belong to a muntjac deer. Poetry fragments from two of my bedside books resonated with me.

This is the earnest work. Each of us is given

only so many mornings to do it—

to look around and love

the oily fur of our lives,

the hoof and the grass-stained muzzle.

Days I don’t do this

I feel the terror of idleness

like a red thirst.

That is from “The Deer,” from Mary Oliver’s House of Light, and reminds me that it’s always worthwhile to get outside and just look. Even if what you’re looking at doesn’t seem to be extraordinary in any way…

Importance leaves me cold,

as does all the information that is classed as ‘news’.

I like those events that the centre ignores:

small branches falling, the slow decay

of wood into humus, how a puddle’s eye

silts up slowly, till, eventually,

the birds can’t bathe there. I admire the edge;

the sides of roads where the ragwort blooms

low but exotic in the traffic fumes;

the scruffy ponies in a scrubland field

like bits of a jigsaw you can’t complete;

the colour of rubbish in a stagnant leat.

There are rarest enjoyments, for connoisseurs

of blankness, an acquired taste,

once recognised, it’s impossible to shake,

this thirst for the lovely commonplace.

(from “Six Poems on Nothing,” III by Gwyneth Lewis, in Parables & Faxes)

This was basically a placeholder post because who knows when I’ll next finish any books and write about them … probably not until later in the month. But I hope you’ve found at least one interesting nugget!

What ‘lovely commonplace’ things are keeping you going this month?

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

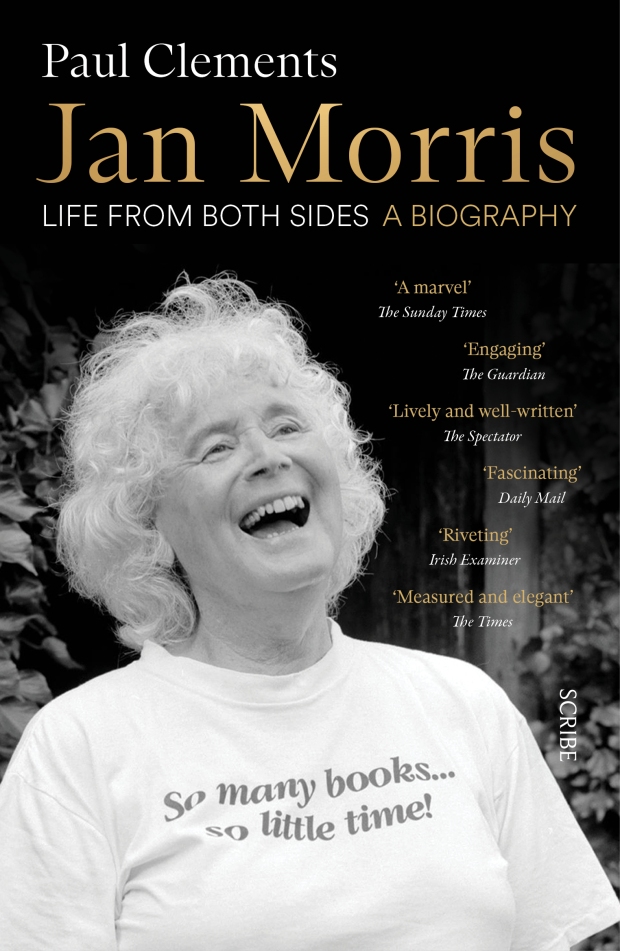

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions. I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

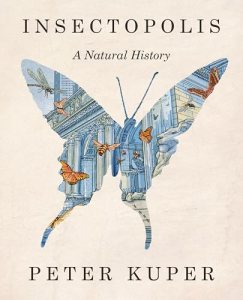

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

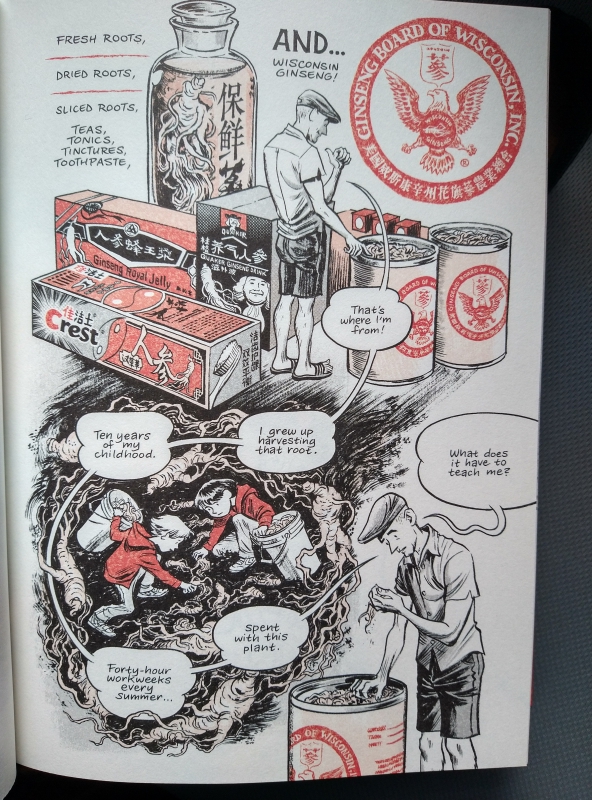

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library) This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.” Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel,

Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel,  The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy)

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy) Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s]

Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s]  Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired  Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut,

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut,  The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy)

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy) Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like  The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun.

The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun. Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved  Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there (

Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there ( Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into…

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into… Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection,

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection,