Book Serendipity, August to October 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- The William Carlos Williams line “no ideas but in things” is quoted in Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman and echoed with a slight adaptation in Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor.

- A woman impulsively stops into a tattoo parlour in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Birdeye by Judith Heneghan.

- Cleaning up a partner’s bristles from the sink in 300 Arguments by Sarah Manguso and The Echoes by Evie Wyld.

- Sarah Manguso, by whom I was reading two books for a Bookmarks article, was quoted in Some of Us Just Fall by Polly Atkin.

- Someone is annoyed at their spouse making a mess cooking lemon preserves in How We Know Our Time Travelers by Anita Felicelli and Liars by Sarah Manguso, both of which are set in California.

- Rumpelstiltskin is referenced in one short story of a speculative collection: How We Know Our Time Travelers by Anita Felicelli and The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer.

- A father who is hard of hearing, and an Australian woman looking for traces of her grandmother’s life in England in The House with All the Lights On by Jessica Kirkness and The Echoes by Evie Wyld.

- A character named Janie or Janey in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston and The Echoes by Evie Wyld. The Pre-Raphaelite model Janey is also mentioned in The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing.

Contrasting one’s childhood love of the Little House on the Prairie books with reading them as an adult and being aware of the racial and colonial implications in Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

Contrasting one’s childhood love of the Little House on the Prairie books with reading them as an adult and being aware of the racial and colonial implications in Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

- A mention of Little Women in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

- A character grew up in a home hair-dressing business in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman.

- The discovery of an old pram in an outbuilding in Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell and Mina’s Matchbox by Yōko Ogawa.

- An Irish woman named Aoife in My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss and Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell.

- Cooking then throwing out entire meals in My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss and The Echoes by Evie Wyld. (Also throwing out a fresh meal in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan. Such scenes distress me!)

A new lover named Simon in one story of The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro and The Echoes by Evie Wyld.

A new lover named Simon in one story of The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro and The Echoes by Evie Wyld.

- A character writes a recommendation letter for someone who then treats them vindictively, because they assumed the letter was negative when it wasn’t, in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and one story of The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro.

- After her parents’ divorce, the author never had a designated bedroom in her father’s house in Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman and The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing.

Reading The Bell Jar as a teenager in Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

Reading The Bell Jar as a teenager in Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

- A contentious Town Hall meeting features in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and Birdeye by Judith Heneghan.

- The wife is pregnant with twins in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs. (There are also twins in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan. In general, I find that they occur far more often in fiction than in real life!)

- 1930s Florida as a setting in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

- Dorothy Wordsworth and her journals are discussed in Some of Us Just Fall by Polly Atkin and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

- Wordsworth’s daffodils are mentioned in Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus and My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss.

- “F*ck off” is delivered in an exaggerated English accent in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan and The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken.

- The main character runs a country store in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston and The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro.

Reading a second novel this year in which the younger sister of a pair wants to go into STEM and joins the Mathletes in high school: first was A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg; later was Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner.

Reading a second novel this year in which the younger sister of a pair wants to go into STEM and joins the Mathletes in high school: first was A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg; later was Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner.

- An older sister who has great trouble attending normal school and so is placed elsewhere (including a mental institution) for a total of two years in Learning to Think by Tracy King and Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner.

- The idea of trees taking revenge on people for environmental destruction in one story of The Secret Life of Insects by Bernardo Esquinca and one poem of The Holy & Broken Bliss by Alicia Ostriker.

- An illiterate character in Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell and Also Here by Brooke Randel.

-

Controversy over throwing a dead body into the trash in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan and Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent.

Controversy over throwing a dead body into the trash in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan and Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent.

- A publishing assistant who wears a miniskirt and Doc Martens in Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- Ancestors’ experience in Auschwitz in Also Here by Brooke Randel and Transgenesis by Ava Winter.

- The protagonist finds it comforting when her boyfriend lies down with his full weight on her in Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner and The Echoes by Evie Wyld.

- A woman badgers her ex-husband about when his affair with his high school/college sweetheart started (before or after the divorce) in Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

I encountered an Irish matriarch who married the ‘wrong’ brother, not Frank, in The Bee Sting by Paul Murray earlier in the year, and then in Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell.

I encountered an Irish matriarch who married the ‘wrong’ brother, not Frank, in The Bee Sting by Paul Murray earlier in the year, and then in Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell.

- A boy is playing in the family car on the driveway when it rolls backwards and kills someone in A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne and Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth Strout.

- Quantoxhead, Somerset is mentioned in On Trying to Keep Still by Jenny Diski and A House Unlocked by Penelope Lively.

- Tapeworms are mentioned in On Trying to Keep Still by Jenny Diski and one story of The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, ed. Lauren Groff.

- A description of horrific teeth in one story of The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, ed. Lauren Groff, and one story of The Long Swim by Terese Svoboda.

- A character researches potato blight, and another keeps his smoking a secret from his wife, in one story of The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, ed. Lauren Groff, and Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth Strout.

A piano gets mauled out of anger in one story of Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse and Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent.

A piano gets mauled out of anger in one story of Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse and Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent.

- Men experiencing eating disorders in Heavy by Kiese Laymon and Heartstopper Volumes 3 and 4 by Alice Oseman.

- Black people deliberately changing their vocabulary and speech register when talking to white people in James by Percival Everett and Heavy by Kiese Laymon.

- My second book of the year in which a woman from centuries ago who magically appears in the present requests to go night clubbing: first The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley, then Isabella & Blodwen by Rachael Smith.

- Characters named Sadie in James by Percival Everett, The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken, and Still Life at Eighty by Abigail Thomas.

- Creepy hares in horror: A Haunting on the Hill by Elizabeth Hand and What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher. There were weird rabbits in I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill, too.

- I read two scenes of a calf being born, one right after the other: in Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter, then I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill.

- I read about an animal scratch leading to infection leading to death in a future with no pharmaceuticals in Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel in the morning and then in the afternoon heard Eve Smith mention the same thing happening due to antibiotic resistance in her novel The Waiting Rooms. Forget about R.I.P.; this is the stuff that scares me…

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

September Releases, Part II: Antrobus, Attenberg, Strout and More

As promised yesterday, I give excerpts of the six (U.S.) September releases I reviewed for Shelf Awareness. But first, my thoughts on a compassionate sequel about a beloved ensemble cast.

Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth Strout

“People always tell you who they are if you just listen”

Alternative title ideas: “Oh Bob!” or “Talk Therapy in Small-Town Maine.” I’ve had a mixed experience with the Amgash novels, of which I’ve now read four. Last year’s Lucy by the Sea was my favourite, a surprisingly successful Covid novel with much to say about isolation, political divisions and how life translates into art. Oh William!, though shortlisted for the Booker, seemed a low point. It’s presented as Lucy’s published memoir about her first husband, but irked me with its precious, scatter-brained writing. For me, Tell Me Everything was closer to the latter. It continues Strout’s newer habit of bringing her various characters together in the same narrative. That was a joy of the previous book, but here it’s overdone and, along with the knowing first-person plural narration (“As we mentioned earlier, housing prices in Crosby, Maine, had been going through the roof since the pandemic”; “Oh Jim Burgess! What are we to do with you?”), feels affected and hokey.

Strout makes it clear from the first line that this novel will mostly be devoted to Bob Burgess, who is not particularly interesting but perhaps a good choice of protagonist for that reason. A 65-year-old semi-retired lawyer, he’s a man of integrity who wins confidences because of his unassuming mien and willingness to listen and help where he can. One doesn’t read Strout for intrigue, but there is actually a mild murder mystery here. Bob ends up defending Matt Beach, a middle-aged man suspected of disposing of his mother’s body in a quarry. The Beaches are odd and damaged, with trauma threading through their history.

Sad stories are indeed the substance of the novel; Lucy trades in them. Literally: on her visits to Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home room, they swap bleak stories of the “unrecorded lives” they have observed or heard about. Lucy and Bob, who are clearly in love with each other, keep up a similar exchange of gloomy tales on their regular walks. Lucy asks Bob and Olive the point of these anecdotes, pondering the very meaning of life. Bob dismisses the question as immature; “as we have said, Bob was not a reflective fellow.” And because the book is filtered through Bob, we, too, feel this is just a piling up of depressing stories. Why should I care about Bob’s ex-wife’s alcoholism, his sister-in-law’s death from cancer, his nephew’s accident? Or any of the other unfortunate occurrences that make up a life. Bob and Lucy are appealingly ordinary characters, yet Strout suggests that they function as secular “sin-eaters,” accepting confessions. Forasmuch as they focus on others, they do each come to terms with childhood trauma and the reality of their marriages. Strout majors on emotional intelligence, but can be clichéd and soundbite-y. Such was my experience of this likable but diffuse novel.

With thanks to Viking (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

Poetry:

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus – The British-Jamaican poet’s intimate third collection contrasts the before and after of becoming a father—a transition that prompts him to reflect on his Deaf and biracial identity as well as the loss of his own father.

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus – The British-Jamaican poet’s intimate third collection contrasts the before and after of becoming a father—a transition that prompts him to reflect on his Deaf and biracial identity as well as the loss of his own father.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor – Factor’s long, intricate second poetry collection envisions womanhood as a tug of war between desire and constraint. “Elegy for a Younger Self” poems string together vivid reminiscences.

Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor – Factor’s long, intricate second poetry collection envisions womanhood as a tug of war between desire and constraint. “Elegy for a Younger Self” poems string together vivid reminiscences.

Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa – The Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate’s debut collection is a tender chronicle of the years leading to his mother’s death from cancer. Food and nature imagery chart the decline in Nkoli’s health and its effect on her family.

Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa – The Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate’s debut collection is a tender chronicle of the years leading to his mother’s death from cancer. Food and nature imagery chart the decline in Nkoli’s health and its effect on her family.

Fiction:

A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg – Her tenth book evinces her mastery of dysfunctional family stories. From the Chicago-area Cohens, the circle widens and retracts as partners and friends enter and exit. Through estrangement and reunion, as characters grapple with sexuality and addictions, the decision is between hiding and figuring out who they are.

A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg – Her tenth book evinces her mastery of dysfunctional family stories. From the Chicago-area Cohens, the circle widens and retracts as partners and friends enter and exit. Through estrangement and reunion, as characters grapple with sexuality and addictions, the decision is between hiding and figuring out who they are.

Nonfiction:

We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood by Jennifer Case – Case’s second book explores the evolution, politics, and culture of contemporary parenthood in 15 intrepid essays. Science and statistics weave through in illuminating ways. This forthright, lyrical study of maternity is an excellent companion read to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence.

We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood by Jennifer Case – Case’s second book explores the evolution, politics, and culture of contemporary parenthood in 15 intrepid essays. Science and statistics weave through in illuminating ways. This forthright, lyrical study of maternity is an excellent companion read to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence.

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan – Ten years after his Booker Prize win for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan revisits his father’s time as a POW—the starting point but ultimately just one thread in this astonishing and uncategorizable work that combines family memoir, biography, and history to examine how love and memory endure. (Published in the USA on 17 September.)

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan – Ten years after his Booker Prize win for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan revisits his father’s time as a POW—the starting point but ultimately just one thread in this astonishing and uncategorizable work that combines family memoir, biography, and history to examine how love and memory endure. (Published in the USA on 17 September.)

With thanks to Emma Finnigan PR and Vintage (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Any other September releases you’d recommend?

Some 2023 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Shortest book read this year: Pitch Black by Youme Landowne and Anthony Horton (40 pages)

Authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood, Deborah Levy and Brian Turner (3 books each); Amy Bloom, Simone de Beauvoir, Tove Jansson, John Lewis-Stempel, W. Somerset Maugham, L.M. Montgomery and Maggie O’Farrell (2 books each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Setting aside the ubiquitous Penguin and its many imprints) Carcanet (11 books) and Picador/Pan Macmillan (also 11), followed by Canongate (7).

My top author discoveries of the year: Michelle Huneven and Julie Marie Wade

My proudest bookish accomplishment: Helping to launch the Little Free Library in my neighbourhood in May, and curating it through the rest of the year (nearly daily tidying; occasional culling; requesting book donations)

Most pinching-myself bookish moments: Attending the Booker Prize ceremony; interviewing Lydia Davis and Anne Enright over e-mail; singing carols after-hours at Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Books that made me laugh: Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson, The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt, two by Katherine Heiny, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Books that made me cry: A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney, Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout, Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Best book club selections: By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah and The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

Shortest book title encountered: Lo (the poetry collection by Melissa Crowe), followed by Bear, Dirt, Milk and They

Best 2023 book titles: These Envoys of Beauty and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore (shame the contents didn’t live up to it!)

Biggest disappointment: Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

A 2023 book that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

The worst books I read this year: Monica by Daniel Clowes, They by Kay Dick, Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy and Self-Portrait in Green by Marie Ndiaye (1-star ratings are extremely rare for me; these were this year’s four)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume. Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year. Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher) Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order) Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted  Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download) Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download) Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer. The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.” Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download) Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.” Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”. John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download) Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download) Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download) The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download) Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.” It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download) Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.” Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy) Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download) Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.” The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download) Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

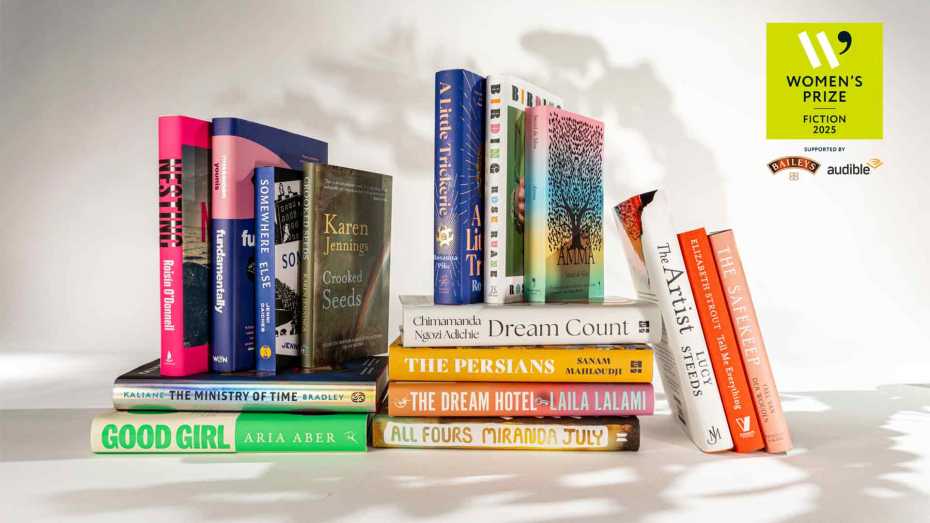

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out.

The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out. The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term.

The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term. Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”

Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”