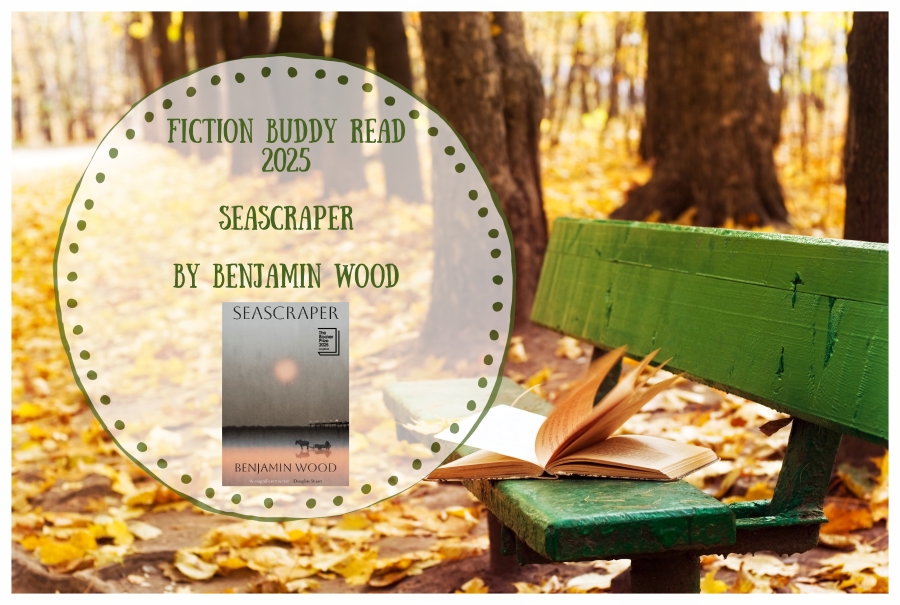

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

Carol Shields Prize Reading: Daughter and Dances

Two more Carol Shields Prize nominees today: from the shortlist, the autofiction-esque story of a father and daughter, both writers, and their dysfunctional family; and, from the longlist, a debut novel about the physical and emotional rigours of being a Black ballet dancer.

Daughter by Claudia Dey

Like her protagonist, Mona Dean, Dey is a playwright, but the Canadian author has clearly stated that her third novel is not autofiction, even though it may feel like it. (Fragmentary sections, fluidity between past and present, a lack of speech marks; not to mention that Dey quotes Rachel Cusk and there’s even a character named Sigrid.) Mona’s father, Paul, is a serial adulterer who became famous for his novel Daughter and hasn’t matched that success in the 20 years since. He left Mona and Juliet’s mother, Natasha, for Cherry, with whom he had another daughter, Eva. There have been two more affairs. Every time Mona meets Paul for a meal or a coffee, she’s returned to a childhood sense of helplessness and conflict.

I had a sordid contract with my father. I was obsessed with my childhood. I had never gotten over my childhood. Cherry had been cruel to me as a child, and I wanted to get back at Cherry, and so I guarded my father’s secrets like a stash of weapons, waiting for the moment I could strike.

It took time for me to warm to Dey’s style, which is full of flat, declarative sentences, often overloaded with character names. The phrasing can be simple and repetitive, with overuse of comma splices. At times Mona’s unemotional affect seems to be at odds with the melodrama of what she’s recounting: an abortion, a rape, a stillbirth, etc. I twigged to what Dey was going for here when I realized the two major influences were Hemingway and Shakespeare.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

And then there’s the King Lear setup. (I caught on to this late, perhaps because I was also reading a more overt Lear update at the time, Private Rites by Julia Armfield.) The larger-than-life father; the two older daughters and younger half-sister; the resentment and estrangement. Dey makes the parallel explicit when Mona, musing on her Hemingway-inspired oeuvre, asks, “Why had Shakespeare not called the play King Lear’s Daughters?”

Were it not for this intertextuality, it would be a much less interesting book. And, to be honest, the style was not my favourite. There were some lines that really irked me (“The flowers they were considering were flamboyant to her eye, she wanted less flamboyant flowers”; “Antoine barked. He was barking.”; “Outside, it sunned. Outside, it hailed.”). However, rather like Sally Rooney, Dey has prioritized straightforward readability. I found that I read this quickly, almost as if in a trance, inexorably drawn into this family’s drama. ![]()

Related reads: Monsters by Claire Dederer, The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright, The Wife by Meg Wolitzer, Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Farrar, Straus and Giroux for the free e-copy for review.

Also from the shortlist:

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Longlisted:

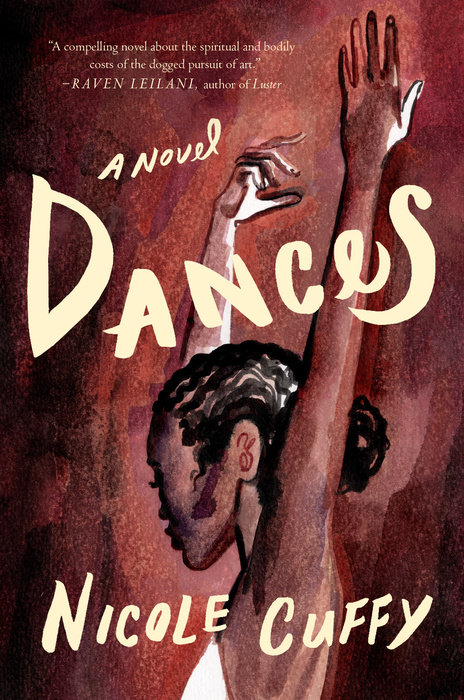

Dances by Nicole Cuffy

This was a buddy read with Laura (see her review); I think we both would have liked to see it on the shortlist as, though we’re not dancers ourselves, we’re attracted to the artistry and physicality of ballet. It’s always a privilege to get an inside glimpse of a rarefied world, and to see people at work, especially in a field that requires single-mindedness and self-discipline. Cuffy’s debut novel focuses on 22-year-old Celine Cordell, who becomes the first Black female principal in the New York City Ballet. Cece marvels at the distance between her Brooklyn upbringing – a single mother and drug-dealing older brother, Paul – and her new identity as a celebrity who has brand endorsements and gets stopped on the street for selfies.

Even though Kaz, the director, insists that “Dance has no race,” Cece knows it’s not true. (And Kaz in some ways exaggerates her difference, creating a role for her in a ballet based around Gullah folklore from South Carolina.) Cece has always had to work harder than the others in the company to be accepted:

Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

A further complication is her relationship with Jasper, her white dance partner. It’s an open secret in the company that they’re together, but to the press they remain coy. Cece’s friends Irine and Ryn support her through rocky times, and her former teachers, Luca and Galina, are steadfast in their encouragement. Late on, Cece’s search for Paul, who has been missing for five years, becomes a surprisingly major element. While the sibling bond helps the novel stand out, I most enjoyed the descriptions of dancing. All of the sections and chapters are titled after ballet terms, and even when I was unfamiliar with the vocabulary or the music being referenced, I could at least vaguely picture all the moves in my head. It takes real skill to render other art forms in words. I’ll look forward to following Cuffy’s career. ![]()

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and One World for the free e-copy for review.

Currently reading:

(Shortlist) Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote

(Longlist) Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad

Up next:

(Longlist) You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy

I’m aiming for one more batch of reviews (and a prediction) before the winner is announced on 13 May.

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

The question posed by Claire Dederer’s third hybrid work of memoir and cultural criticism might be stated thus: “Are we still allowed to enjoy the art made by horrible people?” You might be expecting a hard-line response – prescriptive rules for cancelling the array of sexual predators, drunks, abusers and abandoners (as well as lesser offenders) she profiles. Maybe you’ve avoided Monsters for fear of being chastened about your continuing love of Michael Jackson’s music or the Harry Potter series. I have good news: This book is as compassionate as it is incisive, and while there is plenty of outrage, there is also much nuance.

Dederer begins, in the wake of #MeToo, with film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen, setting herself the assignment of re-watching their masterpieces while bearing in mind their sexual crimes against underage women. In a later chapter she starts referring to this as “the stain,” a blemish we can’t ignore when we consider these artists’ work. Try as we might to recover prelapsarian innocence, it’s impossible to forget allegations of misconduct when watching The Cosby Show or listening to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Nor is it hard to find racism and anti-Semitism in the attitude of many a mid-20th-century auteur.

Does “genius” excuse all? Dederer asks this in relation to Picasso and Hemingway, then counteracts that with a fascinating chapter about Lolita – as far as we know, Nabokov never engaged in, or even contemplated, sex with minors, but he was able to imagine himself into the mind of Humbert Humbert, an unforgettable antihero who did. “The great writer knows that even the blackest thoughts are ordinary,” she writes. Although she doesn’t think Lolita could get published today, she affirms it as a devastating picture of stolen childhood.

“The death of the author” was a popular literary theory in the 1960s that now feels passé. As Dederer notes, in the Internet age we are bombarded with biographical information about favourite writers and musicians. “The knowledge we have about celebrities makes us feel we know them,” and their bad “behavior disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms.” This is not logical, she emphasizes, but instinctive and personal. Some critics (i.e., white men) might be wont to dismiss such emotional responses as feminine. Super-fans are indeed more likely to be women or teenagers, and heartbreak over an idol’s misdoings is bound up with the adoration, and sense of ownership, of the work. She talks with many people who express loyalty “even after everything” – love persists despite it all.

U.S. cover

In a book largely built around biographical snapshots and philosophical questions, Dederer’s struggle to make space for herself as a female intellectual, and write a great book, is a valuable seam. I particularly appreciated her deliberations on the critic’s task. She insists that, much as we might claim authority for our views, subjectivity is unavoidable. “We are all bound by our perspectives,” she asserts; “consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist, which might disrupt the consuming of the art, and the biography of the audience member, which might shape the viewing of the art.”

While men’s sexual predation is a major focus, the book also weighs other sorts of failings: abandonment of children and alcoholism. The “Abandoning Mothers” chapter posits that in the public eye this is the worst sin that a woman can commit. Her two main examples are Doris Lessing and Joni Mitchell, but there are many others she could have mentioned. Even giving more mental energy to work than to childrearing is frowned upon. Dederer wonders if she has been a monster in some ways, and confronts her own drinking problem.

A painting by Cathy Lomax of girls at a Bay City Rollers concert.

Here especially, the project reminded me most of books by Olivia Laing: the same mixture of biographical interrogation, feminist cultural criticism, and memoir as in The Trip to Echo Spring and Everybody; some subjects even overlap (Raymond Carver in the former; Ana Mendieta and Valerie Solanas in the latter – though, unfortunately, these two chapters by Dederer were the ones I thought least necessary; they could easily have been omitted without weakening the argument in any way). I also thought of how Lara Feigel’s Free Woman examines her own life through the prism of Lessing’s.

The danger of being quick to censure any misbehaving artist, Dederer suggests, is a corresponding self-righteousness that deflects from our own faults and hypocrisy. If we are the enlightened ones, we can look back at the casual racism and daily acts of violence of other centuries and say: “1. These people were simply products of their time. 2. We’re better now.” But are we? Dederer redirects all the book’s probing back at us, the audience. If we’re honest about ourselves, and the people we love, we will admit that we are all human and so capable of monstrous acts.

Dederer’s prose is forthright and droll; lucid even when tackling thorny issues. She has succeeded in writing the important book she intended to. Erudite, empathetic and engaging from start to finish, this is one of the essential reads of 2023.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Buy Monsters from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Rathbones Folio Prize 2021 Shortlist Reviews & Prediction

I’ve nearly managed to read the whole Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist before the prize is announced on the evening of Wednesday the 24th. (You can sign up to watch the online ceremony here.) I reviewed the Baume and Ní Ghríofa as part of a Reading Ireland Month post on Saturday, and I’d reviewed the Machado last year in a feature on out-of-the-ordinary memoirs. This left another five books. Because they were short, I’ve been able to read and/or review another four over the past couple of weeks. (The only one unread is As You Were by Elaine Feeney, which I made a false start on last year and didn’t get a chance to try again.)

Nominations come from the Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, so the shortlisted authors have been chosen by an audience of their peers. Indeed, I kept spotting judges’ or fellow nominees’ names in the books’ acknowledgements or blurbs. I tried to think about the eight as a whole and generalize about what the judges were impressed by. This was difficult for such a varied set of books, but I picked out two unifying factors: A distinctive voice, often with a musicality of language – even the books that don’t include poetry per se are attentive to word choice; and timeliness of theme yet timelessness of experience.

Poor by Caleb Femi

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

The Story of Ruthless

Anyone smart enough

to study the food chain

of the estate knew exactly

who this warrior girl was;

once she lined eight boys

up against a wall,

emptied their pockets.

Nobody laughed at the boys.

Another that stood out for me was the two-part “A Designer Talks of Home / A Resident Talks of Home,” a found poem partially constructed from dialogue from a Netflix documentary on interior design. It ironically contrasts airy aesthetic notions with survival in a concrete wasteland. If you loved Surge by Jay Bernard, this should be next on your list.

My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

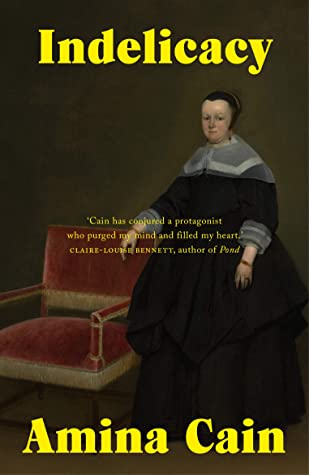

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

The novella belongs to no specific time or place; while Cain lives in Los Angeles, this most closely resembles ‘wan husks’ of European autofiction in translation. Vitória issues pretentious statements as flat as the painting style she claims to love. Some are so ridiculous they end up being (perhaps unintentionally) funny: “We weren’t different from the cucumber, the melon, the lettuce, the apple. Not really.” The book’s most extraordinary passage is her husband’s rambling, defensive monologue, which includes the lines “You’re like an old piece of pie I can’t throw away, a very good pie. But I rescued you.”

It seems this has been received as a feminist story, a cheeky parable of what happens when a woman needs a room of her own but is trapped by her social class. When I read in the Acknowledgements that Cain took lines and character names from Octavia E. Butler, Jean Genet, Clarice Lispector, and Jean Rhys, I felt cheated, as if the author had been engaged in a self-indulgent writing exercise. This was the shortlisted book I was most excited to read, yet ended up being the biggest disappointment.

On the whole, the Folio shortlist ended up not being particularly to my taste this year, but I can, at least to an extent, appreciate why these eight books were considered worthy of celebration. The authors are “writers’ writers” for sure, though in some cases that means they may fail to connect with readers. There was, however, some crossover this year with some more populist prizes like the Costa Awards (Roffey won the overall Costa Book of the Year).

The crystal-clear winner for me is In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado, her memoir of an abusive same-sex relationship. Written in the second person and in short sections that examine her memories from different angles, it’s a masterpiece and a real game changer for the genre – which I’m sure is just what the judges are looking for.

The only book on the shortlist that came anywhere close to this one, for me, was A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, an elegant piece of feminist autofiction that weaves in biography, imagination, and poetry. It would be a fine runner-up choice.

(On the Rathbones Folio Prize Twitter account, you will find lots of additional goodies like links to related articles and interviews, and videos with short readings from each author.)

My thanks to the publishers and FMcM Associates for the free copies for review.

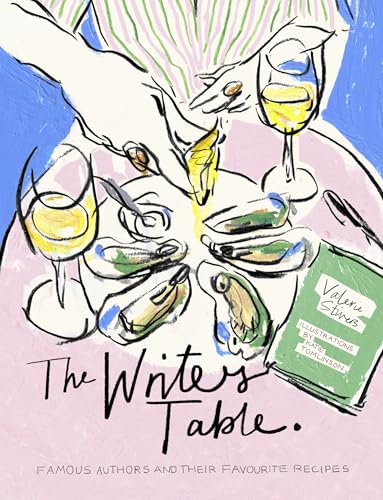

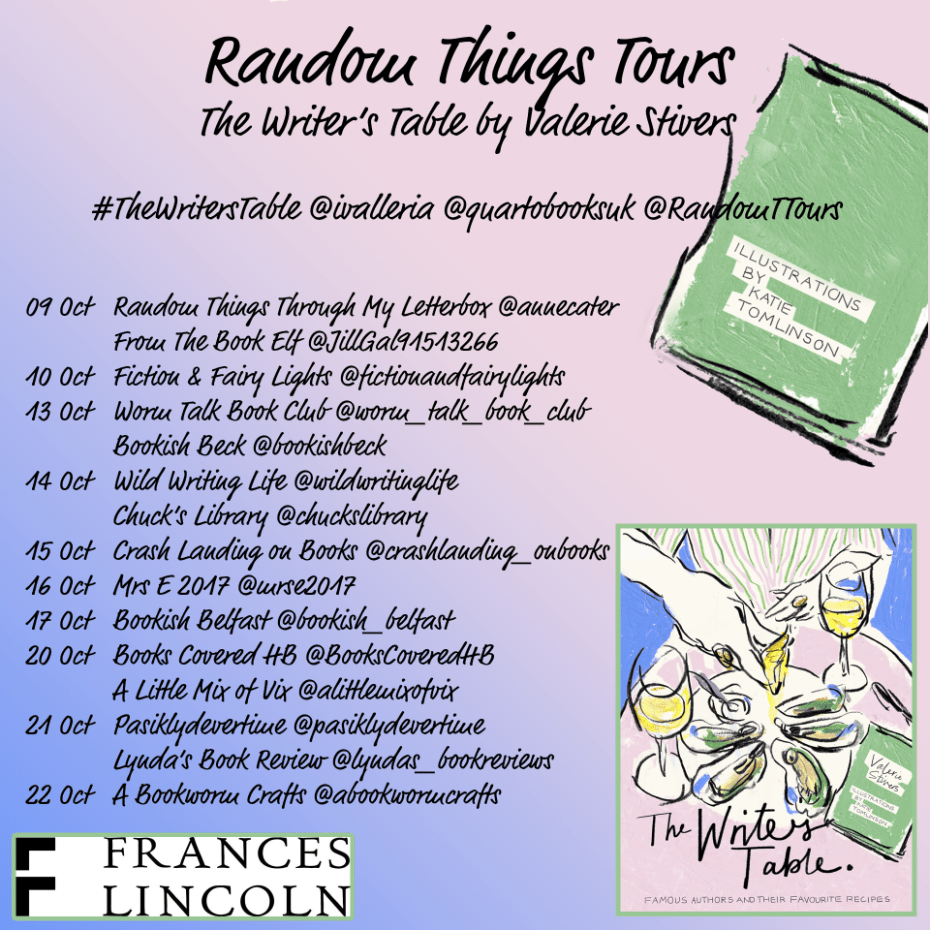

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)  Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as

Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as  Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

There are more than five dozen stories in this slim volume, most just one to three pages and in the first person (55 of 62); bizarre or matter-of-fact slices of life in the Pacific Northwest or California, often with a grandiose title that’s then contradicted by the banality of the contents (e.g., in the three-page “A Short History of Religion in California,” some deer hunters encounter a group of Christian campers). The simple declarative sentences and mentions of drinking and hunting made me think of Carver and Hemingway, but Brautigan is funnier, coming out with the occasional darkly comic zinger. Here’s “The Scarlatti Tilt” in its entirety: “‘It’s very hard to live in a studio apartment in San Jose with a man who’s learning to play the violin.’ That’s what she told the police when she handed them the empty revolver.”

There are more than five dozen stories in this slim volume, most just one to three pages and in the first person (55 of 62); bizarre or matter-of-fact slices of life in the Pacific Northwest or California, often with a grandiose title that’s then contradicted by the banality of the contents (e.g., in the three-page “A Short History of Religion in California,” some deer hunters encounter a group of Christian campers). The simple declarative sentences and mentions of drinking and hunting made me think of Carver and Hemingway, but Brautigan is funnier, coming out with the occasional darkly comic zinger. Here’s “The Scarlatti Tilt” in its entirety: “‘It’s very hard to live in a studio apartment in San Jose with a man who’s learning to play the violin.’ That’s what she told the police when she handed them the empty revolver.”

A debut collection of 16 stories, three of them returning to the same sibling trio. Many of Doyle’s characters are young people who still define themselves by the experiences and romances of their college years. In “That Is Shocking,” Margaret can’t get over the irony of her ex breaking up with her on Valentine’s Day after giving her a plate of heart-shaped scones. Former roommates Christine and Daisy are an example of fading friendship in “Two Pisces Emote about the Passage of Time.”

A debut collection of 16 stories, three of them returning to the same sibling trio. Many of Doyle’s characters are young people who still define themselves by the experiences and romances of their college years. In “That Is Shocking,” Margaret can’t get over the irony of her ex breaking up with her on Valentine’s Day after giving her a plate of heart-shaped scones. Former roommates Christine and Daisy are an example of fading friendship in “Two Pisces Emote about the Passage of Time.”

Minot was new to me (as was Brautigan). These stories were first published between 1991 and 2019, so they span a good chunk of her career. “Polepole” depicts a short-lived affair between two white people in Kenya, one of whom seems to have a dated colonial attitude. In “The Torch,” a woman with dementia mistakes her husband for an old flame. “Occupied” sees Ivy cycling past the NYC Occupy camp on her way to pick up her daughter. The title story, published at LitHub in 2018, is a pithy list of authorial excuses. “Listen” is a nebulous set of lines of unattributed speech that didn’t add up to much for me. “The Language of Cats and Dogs” reminded me of Mary Gaitskill in tone, as a woman remembers her professor’s inappropriate behaviour 40 years later.

Minot was new to me (as was Brautigan). These stories were first published between 1991 and 2019, so they span a good chunk of her career. “Polepole” depicts a short-lived affair between two white people in Kenya, one of whom seems to have a dated colonial attitude. In “The Torch,” a woman with dementia mistakes her husband for an old flame. “Occupied” sees Ivy cycling past the NYC Occupy camp on her way to pick up her daughter. The title story, published at LitHub in 2018, is a pithy list of authorial excuses. “Listen” is a nebulous set of lines of unattributed speech that didn’t add up to much for me. “The Language of Cats and Dogs” reminded me of Mary Gaitskill in tone, as a woman remembers her professor’s inappropriate behaviour 40 years later.

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?” Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension: Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out.

The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out. The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term.

The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term. Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”

Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of