#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

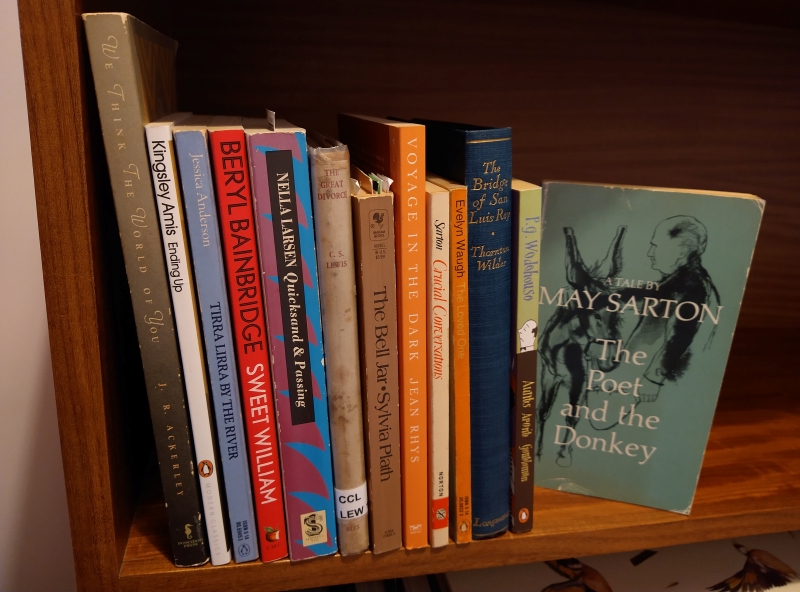

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

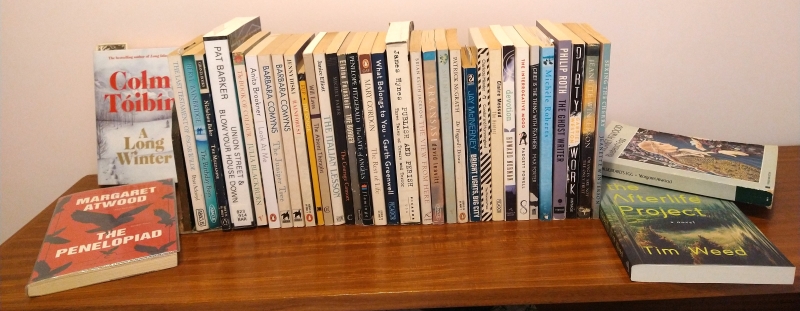

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

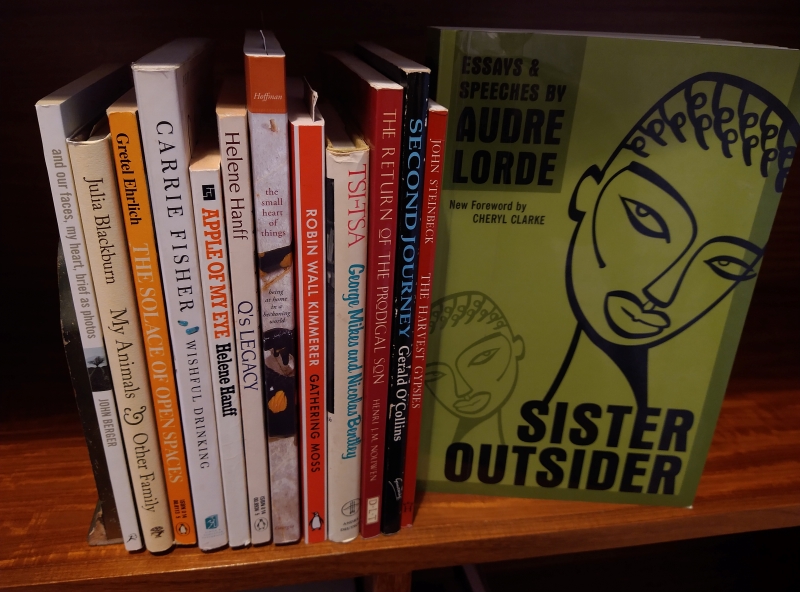

Short Nonfiction

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

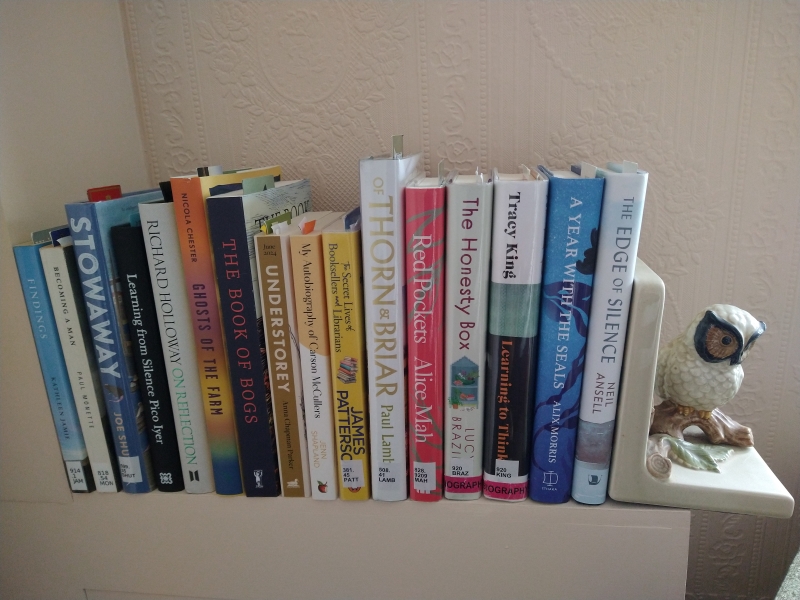

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth: Knulp by Hermann Hesse (1915)

My second contribution to German Literature Month (hosted by Lizzy Siddal) after A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai. This was my first time reading the German-Swiss Nobel Prize winner Hermann Hesse (1877–1962). I had heard of his novels Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, of course, but didn’t know about any of his shorter works before I picked this up from the Little Free Library last month. Knulp is a novella in three stories that provide complementary angles on the title character, a carefree vagabond whose rambling years are coming to an end.

“Early Spring” has a first-person plural narrator, opening “Once, early in the nineties, our friend Knulp had to go to hospital for several weeks.” Upon his discharge he stays with an old friend, the tanner Rothfuss, and spends his time visiting other local tradespeople and casually courting a servant girl. Knulp is a troubadour, writing poems and songs. Without career, family, or home, he lives in childlike simplicity.

He had seldom been arrested and never convicted of theft or mendicancy, and he had highly respected friends everywhere. Consequently, he was indulged by the authorities very much, as a nice-looking cat is indulged in a household, and left free to carry on an untroubled, elegant, splendidly aristocratic and idle existence.

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

In “The End,” Knulp encounters another school friend, Dr. Machold, who insists on sheltering the wayfarer. They’re in their forties but Knulp seems much older because he is ill with tuberculosis. As winter draws in, he resists returning to the hospital, wanting to die as he lived, on his own terms. The book closes with an extraordinary passage in which Knulp converses with God – or his hallucination of such – expressing his regret that he never made more of his talents or had a family. ‘God’ speaks these beautiful words of reassurance:

Look, I wanted you the way you are and no different. You were a wanderer in my name and wherever you went you brought the settled folk a little homesickness for freedom. In my name, you did silly things and people scoffed at you; I myself was scoffed at in you and loved in you. You are my child and my brother and a part of me. There is nothing you have enjoyed and suffered that I have not enjoyed and suffered with you.

I struggle with episodic fiction but have a lot of time for the theme of spiritual questioning. The seasons advance across the stories so that Knulp’s course mirrors the year’s. Knulp could almost be a rehearsal for Stoner: a spare story of the life and death of an Everyman. That I didn’t appreciate it more I put down to the piecemeal nature of the narrative and an unpleasant conversation between Knulp and Machold about adolescent sexual experiences – as in the attempted gang rape scene in Cider with Rosie, it’s presented as boyish fun when part of what Knulp recalls is actually molestation by an older girl cousin. I might be willing to try something else by Hesse. Do give me recommendations! (Little Free Library) ![]()

Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim.

[125 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Ramblin’ Man” by Lemon Jelly

- “I’ve Been Everywhere” by Johnny Cash

- “Rambling Man” by Laura Marling

- “Ballad of a Broken Man” by Duke Special

- “Railroad Man” by Eels

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

#SciFiMonth: A Simple Intervention (#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth) & Station Eleven Reread

It’s rare for me to pick up a work of science fiction but occasionally I’ll find a book that hits the sweet spot between literary fiction and sci-fi. Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell are a few prime examples. It was the comparisons to Margaret Atwood and Kazuo Ishiguro, masters of the speculative, that drew me to my first selection, a Peirene Press novella. My second was a reread, 10 years on, for book club, whose postapocalyptic content felt strangely appropriate for a week that delivered cataclysmic election results.

A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai (2022; 2024)

[Translated from the German by Marielle Sutherland]

Meret is a nurse on a surgical ward, content in the knowledge that she’s making a difference. Her hospital offers a pioneering procedure that cures people of mental illnesses. It’s painless and takes just an hour.

The doctor had to find the affected area and put it to sleep, like a sick animal. That was his job. Mine was to keep the patients occupied. I was to distract them from what was happening and keep them interacting with me. As long as they stayed awake, we knew the doctor and his instruments had found the right place.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

Inokai invites us to ponder whether what we perceive as defects are actually valuable personality traits. More examples of interventions and their aftermath would be a useful point of comparison, though, and the pace is uneven, with a lot of unnecessary-seeming backstory about Meret’s family life. In the letter that accompanied my review copy, Inokai explained her three aims: to portray a nurse (her mother’s career) because they’re underrepresented in fiction, “to explore our yearning to cut out our ‘demons’,” and to offer “a queer love story that was hopeful.” She certainly succeeds with those first and third goals, but with the central subject I felt she faltered through vagueness.

Born in Switzerland, Inokai now lives in Berlin. This also counts as my first contribution to German Literature Month; another is on the way!

[187 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

For synopsis and analysis I can’t do better than when I reviewed this for BookBrowse a few months after its release, so I’d direct you to the full text here. (It’s slightly depressing for me to go back to old reviews and see that I haven’t improved; if anything, I’ve gotten lazier.) A couple book club members weren’t as keen, I think because they’d read a lot of dystopian fiction or seen many postapocalyptic films and found this vision mild and with a somewhat implausible setup and tidy conclusion. But for me this and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road have persisted as THE literary depictions of post-apocalypse life because they perfectly blend the literary and the speculative in an accessible and believable way (this was a National Book Award finalist and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award), contrasting a harrowing future with nostalgia for an everyday life that we can already see retreating into the past.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

The two themes that most struck me this time were the enduring power of art and how societal breakdown would instantly eliminate the international – but compensate for it with the return of the extremely local. At a time when it feels difficult to trust central governments to have people’s best interests at heart, this is a rather comforting prospect. Just in my neighbourhood, I see how we implement this care on a small scale. In settlements of up to a few hundred, the remnants of Station Eleven create something like normal life by Year 20.

Book club members sniped that the characters could have better pooled skills, but we agreed that Mandel was wise to limit what could have been tedious details about survival. “Survival is insufficient,” as the Traveling Symphony’s motto goes (borrowed from Star Trek). Instead, she focuses on love, memory, and hunger for the arts. In some ways, this feels prescient of Covid-19, but even more so of the climate-related collapse I expect in my lifetime. I’ve rated this a little bit higher the second time for its lasting relevance. (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

Some favourite passages:

the whole of Chapter 6, a bittersweet litany that opens “An incomplete list: No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below” and includes “No more pharmaceuticals,” “No more flight,” and “No more countries”

“what made it bearable were the friendships, of course, the camaraderie and the music and the Shakespeare, the moments of transcendent beauty and joy”

“The beauty of this world where almost everyone was gone. If hell is other people, what is a world with almost no people in it?”

Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart by Irmgard Keun (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

My second contribution to German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal, after Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer. I spotted this in a display of new acquisitions at my library earlier in the year and was attracted by the pointillist-modernist style of its cover (Man with a Tulip by Robert Delaunay, 1906) featuring the image of a dandyish yet slightly melancholy young man. I had never heard of the author and assumed it was a man. In fact, Irmgard Keun (1905–82) was a would-be actress who wrote five novels and fled Germany when blacklisted by the Nazis. She was then, variously, a fugitive (returning to Germany only after a false report of her suicide in The Telegraph), a lover of Joseph Roth, a single mother, and an alcoholic. (I love it when a potted author biography reads like a mini-novel!)

Ferdinand (1950) was her last novel and is a curious confection, silly and sombre to equal degrees. It draws on her experiences living by her journalism in bombed-out postwar Cologne. Ferdinand Timpe is a former soldier and POW from a large, eccentric family. His tiny rented room is actually a corridor infested by his landlady Frau Stabhorn’s noisy grandchildren. He’s numb, stumbling from one unsuitable opportunity to another, never choosing his future but letting it happen to him. He once inherited a secondhand bookshop and ran it for a while (I wish we’d heard more about this). Now he’s been talked into writing articles for a weekly paper – it turns out the editor confused him with another Ferdinand. Later he’s hired as a “cheerful adviser” who mostly listens to women complain about their husbands. He is not quite sure how he acquired his own fiancée, Luise, but hopes to weasel out of the engagement.

Each chapter feels like a self-contained story, many of them focusing on particular relatives or friends. There’s his beautiful but immoral cousin, Johanna; his ruthless businessman cousin Magnesius; his lovely but lazy mother, Laura. His descriptions are hilarious, and Keun’s vocabulary really sparkles:

“Like many businesspeople, Magnesius is a jovial and generous party animal, only to emerge as even icier and stonier later. He damascenes himself. To heighten the mood, he has jammed a green monocle in one eye, and pulled a yellow silk stocking over his head. Just now I saw him kissing the hand of a woman unknown to me and offering to buy her a brand-new Mercedes.”

“Luise is a nice girl, and I’ve got nothing against her, but her presence has something oppressive about it for me. I have examined myself and established that this feeling of oppression is not love, and is no prerequisite for marriage, not even an unhappy one. I suppose I should tell her. But I can’t.”

Our antihero gets himself into ridiculous situations, like when he’s down on his luck and pays an impromptu visit to a former professor, Dr Muck, perhaps hoping for a handout; finding him away, he has to await his return for hours while the wife hosts a ladies’ poetry evening:

I was desperate not to fall asleep. Seven times I tiptoed out to the lavatory to take a sip from my flask. In the hall I walked into a sideboard and knocked over a large china ornament – I think it may have been a wood grouse. I broke off a piece of its beak. These things are always happening to me when I’m trying to be especially careful.

Hidden beneath Ferdinand’s hapless and frivolous exterior (he wears a jerkin made from a lady’s coat; Johanna says it makes him looks like “a hurdy-gurdy man’s monkey”), however, is psychological damage. “I feel so deep-frozen. I wonder if I’ll ever thaw out in this life. … Sometimes I feel like wandering on through the entire world. Maybe eventually I’ll run into a place or a person who will make me say yes, this is it, I’ll stay here, this is my home.” His feeling of purposelessness is understandable. Wartime hardship has dented his essential optimism, and external signs of progress – currency reform, denazification – can’t blot out the memory.

There’s a heartbreaking little sequence where he traces his rapid descent into poverty and desperation through cigarettes. He once shuddered at people saving their butts, but then started doing so himself. The same happened with salvaging strangers’ fag-ends from ashtrays. And then, worst of all, rescuing butts from the gutter. “So I never even noticed that one day there was no smoker in the world so degenerate that I could look down on him. I stood so low that no one could stand below me.”

I tend to lose patience with aimless picaresque plots, but this one was worth sticking with for the language and the narrator’s amusing view of the world. I’d happily read another book by Keun if I came across one. Her best known, from the 1930s, are Gilgi and The Artificial Silk Girl.

(Penguin Modern Classics series, 2021. Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. Public library) [172 pages]

Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

This Austrian novella, originally published in German in 2020, also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal. It is Helfer’s fourth book but first to become available in English translation. I picked it up on a whim from a charity shop.

“Memory has to be seen as utter chaos. Only when a drama is made out of it is some kind of order established.”

A family saga in miniature, this has the feel of a family memoir, with the author frequently interjecting to say what happened later or who a certain character would become, yet the focus on climactic scenes – reimagined through interviews with her Aunt Kathe – gives it the shape of autofiction.

Josef and Maria Moosbrugger live on the outskirts of an alpine village with their four children. The book’s German title, Die Bagage, literally means baggage or bearers (Josef’s ancestors were itinerant labourers), but with the connotation of riff-raff, it is applied as an unkind nickname to the impoverished family. When Josef is called up to fight in the First World War, life turns perilous for the beautiful Maria. Rumours spread about her entertaining men up at their remote cottage, such that Josef doubts the parentage of the next child (Grete, Helfer’s mother) conceived during one of his short periods of leave. Son Lorenz resorts to stealing food, and has to defend his mother against the mayor’s advances with a shotgun.

If you look closely at the cover, you’ll see it’s peopled with figures from Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games. Helfer was captivated by the thought of her mother and aunts and uncles as carefree children at play. And despite the challenges and deprivations of the war years, you do get the sense that this was a joyful family. But I wondered if the threats were too easily defused. They were never going to starve because others brought them food; the fending-off-the-mayor scenes are played for laughs even though he very well could have raped Maria.

Helfer’s asides (“But I am getting ahead of myself”) draw attention to how she took this trove of family stories and turned them into a narrative. I found that the meta moments interrupted the flow and made me less involved in the plot because I was unconvinced that the characters really did and said what she posits. In short, I would probably have preferred either a straightforward novella inspired by wartime family history, or a short family memoir with photographs, rather than this betwixt-and-between document.

(Bloomsbury, 2023. Translated from the German by Gillian Davidson. Secondhand purchase from Bas Books and Home, Newbury.) [175 pages]

Letters and Papers from Prison by Dietrich Bonhoeffer (#NovNov22 and #GermanLitMonth)

I’m rounding out our nonfiction week of Novellas in November with a review that also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor and theologian, was hanged at a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 for his role in the Resistance and in planning a failed 1944 assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler.

The version I read (a 1959 Fontana reprint of the 1953 SCM Press edition) is certainly only a selection, as Bonhoeffer’s papers from prison in his Collected Works now run to 800 pages. After some letters to his parents, the largest section here is made up of “Letters to a Friend,” who I take it was the book’s editor, Eberhard Bethge, a seminary student of Bonhoeffer’s and his literary executor as well as his nephew by marriage.

The version I read (a 1959 Fontana reprint of the 1953 SCM Press edition) is certainly only a selection, as Bonhoeffer’s papers from prison in his Collected Works now run to 800 pages. After some letters to his parents, the largest section here is made up of “Letters to a Friend,” who I take it was the book’s editor, Eberhard Bethge, a seminary student of Bonhoeffer’s and his literary executor as well as his nephew by marriage.

Bonhoeffer comes across as steadfast and cheerful. He is grateful for his parents’ care packages, which included his latest philosophy and theology book requests as well as edible treats, and for news of family and acquaintances. To Bethge he expresses concern over the latter’s military service in Italy and delight at his marriage and the birth of a son named Dietrich in his honour. (Among the miscellaneous papers included at the end of this volume are a wedding sermon and thoughts on baptism to tie into those occasions.)

Maintaining a vigorous life of the mind sustained Bonhoeffer through his two years in prison. He downplays the physical challenges of his imprisonment, such as poor food and stifling heat during the summer, acknowledging that the mental toll is more difficult. The rhythm of the Church year is a constant support for him. In his first November there he writes that prison life is like Advent: all one can do is wait and hope. I noted many lines about endurance through suffering and striking a balance between defiance and acceptance:

Resistance and submission are both equally necessary at different times.

It is not some religious act which makes a Christian what he is, but participation in the suffering of God in the life of the world.

not only action, but also suffering is a way to freedom.

Bonhoeffer won over wardens who were happy to smuggle out his letters and papers, most of which have survived apart from a small, late selection that were burned so as not to be incriminating. Any references to the Resistance and the plot to kill Hitler were in code; there are footnotes here to identify them.

The additional non-epistolary material – aphorisms, poems and the abovementioned sermons – is a bit harder going. Although there is plenty of theological content in the letters to Bethge, much of it is comprehensible in context and one could always skip the couple of passages where he goes into more depth.

Reading the foreword and some additional information online gave me an even greater appreciation for Bonhoeffer’s bravery. After a lecture tour of the States in 1939, American friends urged him to stay in the country and not return to Germany. He didn’t take that easier path, nor did he allow a prison guard to help him escape. For as often as he states in his letters the hope that he will be reunited with his parents and friends, he must have known what was coming for him as a vocal opponent of the regime, and he faced it courageously. It blows my mind to think that he died at 39 (my age), and left so much written material behind. His posthumous legacy has been immense.

[Translated from the German by Reginald H. Fuller]

(Free from a fellow church member)

[187 pages]

#NovNov and #GermanLitMonth: The Pigeon and The Appointment

As literature in translation week of Novellas in November continues, I’m making a token contribution to German Literature Month as well. I’m aware that my second title doesn’t technically count towards the challenge because it was originally written in English, but the author is German, so I’m adding it in as a bonus. Both novellas feature an insular perspective and an unusual protagonist whose actions may be slightly difficult to sympathize with.

The Pigeon by Patrick Süskind (1987; 1988)

[Translated from the German by John E. Woods; 77 pages]

At the time the pigeon affair overtook him, unhinging his life from one day to the next, Jonathan Noel, already past fifty, could look back over a good twenty-year period of total uneventfulness and would never have expected anything of importance could ever overtake him again – other than death some day. And that was perfectly all right with him. For he was not fond of events, and hated outright those that rattled his inner equilibrium and made a muddle of the external arrangements of life.

What a perfect opening paragraph! Taking place over about 24 hours in August 1984, this is the odd little tale of a man in Paris who’s happily set in his ways until an unexpected encounter upends his routines. Every day he goes to work as a bank security guard and then returns to his rented room, which he’s planning to buy from his landlady. But on this particular morning he finds a pigeon not a foot from his door, and droppings all over the corridor. Now, I love birds, so this was somewhat difficult for me to understand, but I know that bird phobia is a real thing. Jonathan is so freaked out that he immediately decamps to a hotel, and his day just keeps getting worse from there, in comical ways, until it seems he might do something drastic. The pigeon is both real and a symbol of irrational fears. The conclusion is fairly open-ended, leaving me feeling like this was a short story or unfinished novella. It was intriguing but also frustrating in that sense. There’s an amazing description of a meal, though! (University library)

What a perfect opening paragraph! Taking place over about 24 hours in August 1984, this is the odd little tale of a man in Paris who’s happily set in his ways until an unexpected encounter upends his routines. Every day he goes to work as a bank security guard and then returns to his rented room, which he’s planning to buy from his landlady. But on this particular morning he finds a pigeon not a foot from his door, and droppings all over the corridor. Now, I love birds, so this was somewhat difficult for me to understand, but I know that bird phobia is a real thing. Jonathan is so freaked out that he immediately decamps to a hotel, and his day just keeps getting worse from there, in comical ways, until it seems he might do something drastic. The pigeon is both real and a symbol of irrational fears. The conclusion is fairly open-ended, leaving me feeling like this was a short story or unfinished novella. It was intriguing but also frustrating in that sense. There’s an amazing description of a meal, though! (University library)

(Also reviewed by Cathy and Naomi.)

The Appointment by Katharina Volckmer (2020)

[96 pages]

This debut novella was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize – a mark of experimental style that would often scare me off, so I’m glad I gave it a try anyway. It’s an extended monologue given by a young German woman during her consultation with a Dr Seligman in London. As she unburdens herself about her childhood, her relationships, and her gender dysphoria, you initially assume Seligman is her Freudian therapist, but Volckmer has a delicious trick up her sleeve. A glance at the titles and covers of foreign editions, or even the subtitle of this Fitzcarraldo Editions paperback, would give the game away, so I recommend reading as little as possible about the book before opening it up. The narrator has some awfully peculiar opinions, especially in relation to Nazism (the good doctor being a Jew), but the deeper we get into her past the more we see where her determination to change her life comes from. This was outrageous and hilarious in equal measure, and great fun to read. I’d love to see someone turn it into a one-act play. (New purchase)

This debut novella was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize – a mark of experimental style that would often scare me off, so I’m glad I gave it a try anyway. It’s an extended monologue given by a young German woman during her consultation with a Dr Seligman in London. As she unburdens herself about her childhood, her relationships, and her gender dysphoria, you initially assume Seligman is her Freudian therapist, but Volckmer has a delicious trick up her sleeve. A glance at the titles and covers of foreign editions, or even the subtitle of this Fitzcarraldo Editions paperback, would give the game away, so I recommend reading as little as possible about the book before opening it up. The narrator has some awfully peculiar opinions, especially in relation to Nazism (the good doctor being a Jew), but the deeper we get into her past the more we see where her determination to change her life comes from. This was outrageous and hilarious in equal measure, and great fun to read. I’d love to see someone turn it into a one-act play. (New purchase)

A favourite passage:

But then we are most passionate when we worship the things that don’t exist, like race, or money, or God, or, quite simply, our fathers. God, of course, was a man too. A father who could see everything, from whom you couldn’t even hide in the toilet, and who was always angry. He probably had a penis the size of a cigarette.

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages] I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction (

I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction ( This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]