Four for #NonfictionNovember and #NovNov25: Hanff, Humphrey, Kimmerer & Steinbeck

I’ll be doubling up posts most days for the rest of this month to cram everything in!

Today I have a cosy companion story to a beloved bibliophiles’ classic, a comprehensive account of my favourite beverage, a refreshing Indigenous approach to economics, and a journalistic exposé that feels nearly as relevant now as it did 90 years ago.

Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff (1985)

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages]

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages] ![]()

Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey (2020)

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages]

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages] ![]()

The Serviceberry: An Economy of Gifts and Abundance by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2024)

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages]

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages] ![]()

The Harvest Gypsies: On the Road to The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (1936; 1988)

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages]

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages] ![]()

Check out Kris Drever’s folk song “Harvest Gypsies” (written by Boo Hewerdine) here.

My Year in Novellas (#NovNov24)

Here at the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about the novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a special shelf of short books that I add to throughout the year. When at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, a Little Free Library, or the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about my piles for November. But I do read novellas at other times of year, too. Forty-four of them between December 2023 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year it was 46, so it seems like that’s par for the course). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My favourites of the ones I’ve already covered on the blog would probably be (nonfiction) Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti and (fiction) Aimez-vous Brahms by Françoise Sagan. My proudest achievements are: reading the short graphic novel Broderies by Marjane Satrapi in the original French at our Parisian Airbnb in December; and managing two rereads: Heartburn by Nora Ephron and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Of the short books I haven’t already reviewed here, I’ve chosen two gems, one fiction and one nonfiction, to spotlight in this post:

Fiction

Clear by Carys Davies

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

In my book club, opinions differed slightly as to the central relationship and the conclusion, but we agreed that it was beautifully done, with so much conveyed in the concise length. This received our highest rating ever, in fact. I’d read Davies’ West and not appreciated it as much, although looking back I can see that it was very similar: one or a few character(s) embarked on unusual and intense journey(s); a plucky female character; a heavy sense of threat; and an improbably happy ending. It was the ending that seemed to come out of nowhere and wasn’t in keeping with the tone of the rest of the novella that made me mark West down. Here I found the writing cinematic and particularly enjoyed Mary as a strong character who escaped spinsterhood but even in marriage blazes her own trail and is clever and creative enough to imagine a new living situation. And although the ending is sudden and surprising, it nevertheless seems to arise naturally from what we know of the characters’ emotional development – but also sent me scurrying back to check whether there had been hints. One of my books of the year for sure. ![]()

Nonfiction

A Termination by Honor Moore

Poet and memoirist Honor Moore’s A Termination is a fascinatingly discursive memoir that circles her 1969 abortion and contrasts societal mores across her lifetime.

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

Family and social factors put Moore’s experiences into perspective. The first doctor she saw refused Moore’s contraception request because she was unmarried. Her mother, however, bore nine children and declined to abort a pregnancy when advised to do so for medical reasons. Moore observes that she made her own decision almost 10 years before “the word choice replaced pro abortion.”

This concise work is composed of crystalline fragments. The stream of consciousness moves back and forth in time, incorporating occasional second- and third-person narration as well as highbrow art and literature references. Moore writes one scene as if it’s in a play and imagines alternative scenarios in which she has a son; though she is curious, she is not remorseful. The granular attention to women’s lives recalls Annie Ernaux, while the kaleidoscopic yet fluid approach is reminiscent of Sigrid Nunez’s work. It’s a stunning rendering of steps on her childfree path. ![]()

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I currently have four novellas underway and plan to start some more this weekend. I have plenty to choose from!

Everyone’s getting in on the act: there’s an article on ‘short and sweet books’ in the November/December issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I’m an associate editor; Goodreads sent around their usual e-mail linking to a list of 100 books under 250 or 200 pages to help readers meet their 2024 goal. Or maybe you’d like to join in with Wafer Thin Books’ November buddy read, the Ugandan novella Waiting by Goretti Kyomuhendo (2007).

Why not share some recent favourite novellas with us in a post of your own?

Literary Wives Club: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

This is one of those classics I’ve been hearing about for decades and somehow never read – until now. Right from the start, I could spot its influence on African American writers such as Toni Morrison. Hurston deftly reproduces the all-Black milieu of Eatonville, Florida, bringing characters to life through folksy speech and tying into a venerable tradition through her lyrical prose. As the novel opens, Janie Crawford, forty years old but still a looker, sets tongues wagging when she returns to town “from burying the dead.” Her friend Pheoby asks what happened and the narrative that unfolds is Janie’s account of her three marriages.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER!}

- To protect Janie’s reputation and prospects, her grandmother, who grew up in the time of slavery, marries Janie off to an old farmer, Logan Killicks, at age 16. He works her hard and treats her no better than one of his animals.

- She then runs off with handsome, ambitious Joe Starks. [A comprehension question here: was Janie technically a bigamist? I don’t recall there being any explanation of her getting an annulment or divorce.] He opens a general store and becomes the town mayor. Janie is, again, a worker, but also a trophy wife. While the townspeople gather on the porch steps to shoot the breeze, he expects her to stay behind the counter. The few times we hear her converse at length, it’s clear she’s wise and well-spoken, but in the 20 years they are together Joe never allows her to come into her own. He also hits her. “The years took all the fight out of Janie’s face.” When Joe dies of kidney failure, she is freer than before: a widow with plenty of money in the bank.

- Nine months after Joe’s death, Janie is courted by Vergible Woods, known to all as “Tea Cake.” He is about a decade younger than her (Joe was a decade older, but nobody made a big deal out of that), but there is genuine affection and attraction between them. Tea Cake is a lovable scoundrel, not to be trusted around money or other women. They move down to the Everglades and she joins him as an agricultural labourer. The difference between this and being Killicks’ wife is that Janie takes on the work voluntarily, and they are equals there in the field and at home.

In my favourite chapter, a hurricane hits. The title comes from this scene and gives a name to Fate. Things get really melodramatic from this point, though: during their escape from the floodwaters, Tea Cake has to fend off a rabid dog to save Janie. He is bitten and contracts rabies which, untreated, leads to madness. When he comes at Janie with a pistol, she has to shoot him with a rifle. A jury rules it an accidental death and finds Janie not guilty.

I must admit that I quailed at pages full of dialogue – dialect is just hard to read in large chunks. Maybe an audiobook or film would be a better way to experience the story? But in between, Hurston’s exposition really impressed me. It has scriptural, aphoristic weight to it. Get a load of her opening and closing paragraphs:

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Here was peace. [Janie] pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

There are also beautiful descriptions of Janie’s state of mind and what she desires versus what she feels she has to settle for. “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.” She envisions happiness as sitting under a pear tree; bees buzzing in the blossom above and all the time in the world for contemplation. (It was so pleasing when I realized this is depicted on the Virago Modern Classics cover.)

I was delighted that the question of having babies simply never arises. No one around Janie brings up motherhood, though it must have been expected of her in that time and community. Her first marriage was short and, we can assume, unconsummated; her second gradually became sexless; her third was joyously carnal. However, given that both she and her mother were born of rape, she may have had traumatic associations with pregnancy and taken pains to prevent it. Hurston doesn’t make this explicit, yet grants Janie freedom to take less common paths.

What with the symbolism, the contrasts, the high stakes and the theatrical tragedy, I felt this would be a good book to assign to high school students instead of or in parallel with something by John Steinbeck. I didn’t fall in love with it in the way Zadie Smith relates in her introduction, but I did admire it and was glad to finally experience this classic of African American literature. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- A marriage without love is miserable. Marriage is not a cure for loneliness.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the unmated? Did marriage compel love like the sun the day?

(These are rhetorical questions, but the answer is NO.)

- Every marriage is different. But it works best when there is equality of labour, status and finances. Marriage can change people.

Pheoby says to Janie when she confesses that she’s thinking about marrying Tea Cake, “you’se takin’ uh awful chance.” Janie replies, “No mo’ than Ah took befo’ and no mo’ than anybody else takes when dey gits married. It always changes folks, and sometimes it brings out dirt and meanness dat even de person didn’t know they had in ’em theyselves.”

Later Janie says, “love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch. Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

This was a perfect book to illustrate the sorts of themes we usually discuss!

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in December: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (about Sylvia Plath)

Rereading Of Mice and Men for #1937Club

A year club hosted by Karen and Simon is always a great excuse to read more classics. Between my shelves and the library, I had six options for 1937. But I started reading too late, and had too many books on the go, to finish more than one – a reread. No matter; it was a good one I was glad to revisit, and I’ll continue with the other reread at my own pace.

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Are teenagers doomed to dislike the books they read in school? I think this must have been on the curriculum for 11th grade English. It was my third Steinbeck novella after The Red Pony and The Pearl, so to me it confirmed that he wrote contrived, depressing stuff with lots of human and animal suffering. Not until I read The Grapes of Wrath in college and East of Eden (THE Great American Novel) five years ago did I truly recognize Steinbeck’s greatness.

Are teenagers doomed to dislike the books they read in school? I think this must have been on the curriculum for 11th grade English. It was my third Steinbeck novella after The Red Pony and The Pearl, so to me it confirmed that he wrote contrived, depressing stuff with lots of human and animal suffering. Not until I read The Grapes of Wrath in college and East of Eden (THE Great American Novel) five years ago did I truly recognize Steinbeck’s greatness.

George and Lennie are itinerant farm workers in Salinas Valley, California. Lennie is a gentle giant, intellectually disabled and aware of his own strength when hauling sacks of barley but not when stroking mice and puppies. George looks after Lennie as a favour to Aunt Clara and they’re saving up to buy their own smallholding. This dream is repeated to the point of legend, somewhere between a bedtime story and scripture:

‘Someday—we’re gonna get the jack together and we’re gonna have a little house and a couple of acres an’ a cow and some pigs and—’ ‘An’ live off the fatta the lan’,’ Lennie shouted. ‘And have rabbits.’

They quickly settle in alongside the other ranch-hands and even convert two to their idyllic picture of independence. But the foreman, Curley, is a hothead and his bored would-be-starlet wife won’t stop roaming into the men’s quarters. No matter how much George tells Lennie to stay away from both of them, something is set in motion – an inevitable repeat of an incident from their previous employment that forced them to move on.

I remembered the main contours here but not the ultimate ending, and this time I appreciated the deliberate echoes and heavy foreshadowing (all that symbolism to write formulaic school essays about!): this is Shakespearean tragedy with the signs and stakes writ large against a limited background. Bar some paragraphs of scene-setting descriptions, it is like a play; no surprise it’s been filmed several times. (I wish I didn’t have danged John Malkovich in my head as Lennie; I can’t think of anyone else in that role, whereas Gary Sinise doesn’t necessarily epitomize George for me.) The characterization of the one Black character, Crooks, and the one woman are uncomfortably of their time. However, Crooks is given the dubious honour of conveying the bleak vision: “Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It’s just in their head.” Like Hardy, Steinbeck knows what happens when the lower classes make the mistake of wanting too much. It’s a timeless tale of grit and desperation, the kind one can’t imagine not existing. (Public library)

Apposite listening: “The Great Defector” by Bell X1 (known for their quirky lyrics):

You’ve been teasing us farm boys

’til we start talking ’bout those rabbits, George

oh, won’t you tell us ’bout those rabbits, George?

Original rating (1999?): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Currently rereading: The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien – My father gave me this for Christmas when I was 10. I think I finally read it sometime in my later teens, about when the Lord of the Rings films were coming out. I’m on page 70 now. I’d forgotten just how funny Tolkien is about the set-in-his-ways Bilbo and his devotion to a cosy, quiet life. When he’s roped into a quest to reclaim a mountain hoard of treasure from a dragon – along with 13 dwarves and Gandalf the wizard – he realizes he has much discomfort and many a missed meal ahead of him.

DNFed: Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb – My second attempt with Hungarian literature, and I found it curiously similar to the other novel I’d read (Embers by Sandor Márai) in that much of it, at least the 50 pages I read, is a long story told by one character to another. In this case, Mihály, on his Italian honeymoon, tells his wife about his childhood best friends, a brother and sister. I wondered if I was meant to sense homoerotic attachment between Mihály and Tamás, which would appear to doom this marriage right at its outset. (Secondhand – Edinburgh charity shop, 2018)

DNFed: Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb – My second attempt with Hungarian literature, and I found it curiously similar to the other novel I’d read (Embers by Sandor Márai) in that much of it, at least the 50 pages I read, is a long story told by one character to another. In this case, Mihály, on his Italian honeymoon, tells his wife about his childhood best friends, a brother and sister. I wondered if I was meant to sense homoerotic attachment between Mihály and Tamás, which would appear to doom this marriage right at its outset. (Secondhand – Edinburgh charity shop, 2018)

Skimmed: Out of Africa by Karen Blixen – I enjoyed the prose style but could tell I’d need a long time to wade through the detail of her life on a coffee farm in Kenya, and would probably have to turn a blind eye to the expected racism of the anthropological observation of the natives. (Secondhand – Way’s in Henley, 2015)

Skimmed: Out of Africa by Karen Blixen – I enjoyed the prose style but could tell I’d need a long time to wade through the detail of her life on a coffee farm in Kenya, and would probably have to turn a blind eye to the expected racism of the anthropological observation of the natives. (Secondhand – Way’s in Henley, 2015)

Here’s hoping for a better showing next time!

(I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, and 1940 Club.)

Other 2019 Superlatives and Some Statistics

My best discoveries of the year: The poetry of Tishani Doshi; Penelope Lively and Elizabeth Strout (whom I’d read before but not fully appreciated until this year); also, the classic nature writing of Edwin Way Teale.

The authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood and Janet Frame (each: 2 whole books plus parts of 2 more), followed by Doris Lessing (2 whole books plus part of 1 more), followed by Miriam Darlington, Paul Gallico, Penelope Lively, Rachel Mann and Ben Smith (each: 2 books).

Debut authors whose next work I’m most looking forward to: John Englehardt, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt, Gail Simmons and Lara Williams.

My proudest reading achievement: A 613-page novel in verse (Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly) + 2 more books of over 600 pages (East of Eden by John Steinbeck and Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese).

Best book club selection: Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay was our first nonfiction book and received our highest score ever.

Some best first lines encountered this year:

“What can you say about a twenty-five-year old girl who died?” (Love Story by Erich Segal)

“What can you say about a twenty-five-year old girl who died?” (Love Story by Erich Segal)- “The women of this family leaned towards extremes” (Away by Jane Urquhart)

- “The day I returned to Templeton steeped in disgrace, the fifty-foot corpse of a monster surfaced in Lake Glimmerglass.” (from The Monsters of Templeton by Lauren Groff)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Lanny by Max Porter

The 2019 books everybody else loved (or so it seems), but I didn’t: Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, The Topeka School by Ben Lerner, Underland by Robert Macfarlane, The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse by Charlie Mackesy, Three Women by Lisa Taddeo and The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

The year’s major disappointments: Cape May by Chip Cheek, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer, Letters to the Earth: Writing to a Planet in Crisis, ed. Anna Hope et al., Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken, Rough Magic: Riding the World’s Loneliest Horse Race by Lara Prior-Palmer, The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal, The Knife’s Edge by Stephen Westaby and Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

The year’s major disappointments: Cape May by Chip Cheek, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer, Letters to the Earth: Writing to a Planet in Crisis, ed. Anna Hope et al., Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken, Rough Magic: Riding the World’s Loneliest Horse Race by Lara Prior-Palmer, The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal, The Knife’s Edge by Stephen Westaby and Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

The worst book I read this year: Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

Some statistics on my 2019 reading:

Fiction: 45.4%

Nonfiction: 43.4%

Poetry: 11.2%

(As usual, fiction and nonfiction are neck and neck. I read a bit more poetry this year than last.)

Male author: 39.4%

Female author: 58.9%

Nonbinary author (the first time this category has been applicable for me): 0.85%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 0.85%

(I’ve said this the past three years: I find it interesting that female authors significantly outweigh male authors in my reading; I have never consciously set out to read more books by women.)

E-books: 10.3%

Print books: 89.7%

(My e-book reading has been declining year on year, partially because I’ve cut back on the reviewing gigs that involve only reading e-books and partially because I’ve done less traveling; also, increasingly, I find that I just prefer to sit down with a big stack of print books.)

Work in translation: 7.2%

(Lower than I’d like, but better than last year’s 4.8%.)

Where my books came from for the whole year:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 36.8%

- Public library: 21.3%

- Secondhand purchase: 13.8%

- Free (giveaways, The Book Thing of Baltimore, the free mall bookshop, etc.): 9.2%

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss or Project Gutenberg: 7.8%

- Gifts: 4.3%

- University library: 2.9%

- New purchase (usually at a bargain price): 2.9%

- Church theological library: 0.8%

- Borrowed: 0.2%

(Review copies accounted for over a third of my reading; I’m going to scale way back on this next year. My library reading was similar to last year’s; my e-book reading decreased in general; I read more books that I either bought new or got for free.)

Number of unread print books in the house: 440

(Last thing I knew the figure was more like 300, so this is rather alarming. I blame the free mall bookshop, where I volunteer every Friday. Most weeks I end up bringing home at least a few books, but it’s often a whole stack. Surely you understand. Free books! No strings attached!)

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

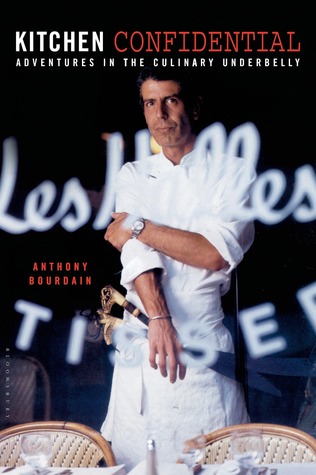

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast. (20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.

(20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right. Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

Anything by Bill Bryson

Anything by Bill Bryson

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott Faces in the Water by Janet Frame: The best inside picture of mental illness I’ve read. Istina Mavet, in and out of New Zealand mental hospitals between ages 20 and 28, undergoes regular shock treatments. Occasional use of unpunctuated, stream-of-consciousness prose is an effective way of conveying the protagonist’s terror. Simply stunning writing.

Faces in the Water by Janet Frame: The best inside picture of mental illness I’ve read. Istina Mavet, in and out of New Zealand mental hospitals between ages 20 and 28, undergoes regular shock treatments. Occasional use of unpunctuated, stream-of-consciousness prose is an effective way of conveying the protagonist’s terror. Simply stunning writing. The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver: What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. Christianity and colonialism have a lot to answer for. A masterpiece.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver: What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. Christianity and colonialism have a lot to answer for. A masterpiece. The Grass Is Singing by Doris Lessing: Begins with the words “MURDER MYSTERY”: a newspaper headline announcing that Mary, wife of Rhodesian farmer Dick Turner, has been found murdered by their houseboy. The breakdown of a marriage and the failure of a farm form a dual tragedy that Lessing explores in searing psychological detail.

The Grass Is Singing by Doris Lessing: Begins with the words “MURDER MYSTERY”: a newspaper headline announcing that Mary, wife of Rhodesian farmer Dick Turner, has been found murdered by their houseboy. The breakdown of a marriage and the failure of a farm form a dual tragedy that Lessing explores in searing psychological detail. Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively: Seventy-six-year-old Claudia Hampton, on her deathbed in a nursing home, determines to write a history of the world as she’s known it. More impressive than the plot surprises is how Lively packs the whole sweep of a life into just 200 pages, all with such rich, wry commentary on how what we remember constructs our reality.

Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively: Seventy-six-year-old Claudia Hampton, on her deathbed in a nursing home, determines to write a history of the world as she’s known it. More impressive than the plot surprises is how Lively packs the whole sweep of a life into just 200 pages, all with such rich, wry commentary on how what we remember constructs our reality. The Friend by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is a writer and academic who has stepped up to care for her late friend’s aging Great Dane, Apollo. It feels like Nunez has encapsulated everything she’s ever known or thought about, all in just over 200 pages, and alongside a heartwarming little plot. (Animal lovers need not fear.)

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is a writer and academic who has stepped up to care for her late friend’s aging Great Dane, Apollo. It feels like Nunez has encapsulated everything she’s ever known or thought about, all in just over 200 pages, and alongside a heartwarming little plot. (Animal lovers need not fear.) There There by Tommy Orange: Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least. The novel cycles through most of the characters multiple times, so gradually we work out the links between everyone. Hugely impressive.

There There by Tommy Orange: Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least. The novel cycles through most of the characters multiple times, so gradually we work out the links between everyone. Hugely impressive. In the Driver’s Seat by Helen Simpson: The best story collection I read this year. Themes include motherhood, death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. Gentle humor and magic tempers the sadness. I especially liked “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour lunch break walk.

In the Driver’s Seat by Helen Simpson: The best story collection I read this year. Themes include motherhood, death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. Gentle humor and magic tempers the sadness. I especially liked “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour lunch break walk. East of Eden by John Steinbeck: Look no further for the Great American Novel. Spanning from the Civil War to World War I and crossing the country from New England to California, this is just as wide-ranging in its subject matter, with an overarching theme of good and evil as it plays out in families and in individual souls.

East of Eden by John Steinbeck: Look no further for the Great American Novel. Spanning from the Civil War to World War I and crossing the country from New England to California, this is just as wide-ranging in its subject matter, with an overarching theme of good and evil as it plays out in families and in individual souls. Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese: The saga of conjoined twins born of a union between an Indian nun and an English surgeon in 1954. Ethiopia’s postcolonial history is a colorful background. I thrilled to the accounts of medical procedures. I can’t get enough of sprawling Dickensian stories full of coincidences, minor characters, and humor and tragedy.

Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese: The saga of conjoined twins born of a union between an Indian nun and an English surgeon in 1954. Ethiopia’s postcolonial history is a colorful background. I thrilled to the accounts of medical procedures. I can’t get enough of sprawling Dickensian stories full of coincidences, minor characters, and humor and tragedy. Extinctions by Josephine Wilson: The curmudgeonly antihero is widower Frederick Lothian, at age 69 a reluctant resident of St Sylvan’s Estate retirement village. It’s the middle of a blistering Australian summer and he has plenty of time to drift back over his life. He’s a retired engineering expert, but he’s been much less successful in his personal life.

Extinctions by Josephine Wilson: The curmudgeonly antihero is widower Frederick Lothian, at age 69 a reluctant resident of St Sylvan’s Estate retirement village. It’s the middle of a blistering Australian summer and he has plenty of time to drift back over his life. He’s a retired engineering expert, but he’s been much less successful in his personal life. Windfall by Miriam Darlington: I’d had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing. The verse is rooted in the everyday. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re still mourning Mary Oliver.

Windfall by Miriam Darlington: I’d had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing. The verse is rooted in the everyday. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re still mourning Mary Oliver. Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods by Tishani Doshi: The third collection by the Welsh–Gujarati poet and dancer is vibrant and boldly feminist. The tone is simultaneously playful and visionary, toying with readers’ expectations. Several of the most arresting poems respond to the #MeToo movement. She also excels at crafting breath-taking few-word phrases.

Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods by Tishani Doshi: The third collection by the Welsh–Gujarati poet and dancer is vibrant and boldly feminist. The tone is simultaneously playful and visionary, toying with readers’ expectations. Several of the most arresting poems respond to the #MeToo movement. She also excels at crafting breath-taking few-word phrases. Where the Road Runs Out by Gaia Holmes: A major thread of the book is caring for her father at home and in the hospital as he was dying on the Orkney Islands – a time of both wonder and horror. Other themes include pre-smartphone life and a marriage falling apart. There are no rhymes, just alliteration and plays on words, with a lot of seaside imagery.

Where the Road Runs Out by Gaia Holmes: A major thread of the book is caring for her father at home and in the hospital as he was dying on the Orkney Islands – a time of both wonder and horror. Other themes include pre-smartphone life and a marriage falling apart. There are no rhymes, just alliteration and plays on words, with a lot of seaside imagery. Autumn Journal by Louis MacNeice: MacNeice wrote this long verse narrative between August 1938 and the turn of the following year. Everyday life for the common worker muffles political rumblings that suggest all is not right in the world. He reflects on his disconnection from Ireland; on fear, apathy and the longing for purpose. Still utterly relevant.

Autumn Journal by Louis MacNeice: MacNeice wrote this long verse narrative between August 1938 and the turn of the following year. Everyday life for the common worker muffles political rumblings that suggest all is not right in the world. He reflects on his disconnection from Ireland; on fear, apathy and the longing for purpose. Still utterly relevant. Sky Burials by Ben Smith: I discovered Smith through the 2018 New Networks for Nature conference. He was part of a panel discussion on the role poetry might play in environmental activism. This collection shares that environmentalist focus. Many of the poems are about birds. There’s a sense of history but also of the future.

Sky Burials by Ben Smith: I discovered Smith through the 2018 New Networks for Nature conference. He was part of a panel discussion on the role poetry might play in environmental activism. This collection shares that environmentalist focus. Many of the poems are about birds. There’s a sense of history but also of the future. Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness by Lyanda Lynn Haupt: During a bout of depression, Haupt decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. A charming record of bird behavior and one woman’s reawakening, but also a bold statement of human responsibility to the environment.

Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness by Lyanda Lynn Haupt: During a bout of depression, Haupt decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. A charming record of bird behavior and one woman’s reawakening, but also a bold statement of human responsibility to the environment. All Things Consoled: A Daughter’s Memoir by Elizabeth Hay: Hay’s parents, Gordon and Jean, stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home. There are many harsh moments in this memoir, but almost as many wry ones, with Hay picking just the right anecdotes to illustrate her parents’ behavior and the shifting family dynamic.

All Things Consoled: A Daughter’s Memoir by Elizabeth Hay: Hay’s parents, Gordon and Jean, stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home. There are many harsh moments in this memoir, but almost as many wry ones, with Hay picking just the right anecdotes to illustrate her parents’ behavior and the shifting family dynamic. Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay: Jackie Kay was born out of the brief relationship between a Nigerian student and a Scottish nurse in Aberdeen in the early 1960s. This memoir of her search for her birth parents is a sensitive treatment of belonging and (racial) identity. Kay writes with warmth and a quiet wit. The nonlinear structure is like a family photo album.

Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay: Jackie Kay was born out of the brief relationship between a Nigerian student and a Scottish nurse in Aberdeen in the early 1960s. This memoir of her search for her birth parents is a sensitive treatment of belonging and (racial) identity. Kay writes with warmth and a quiet wit. The nonlinear structure is like a family photo album. Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp: An excellent addiction memoir that stands out for its smooth and candid writing. For nearly 20 years, Knapp was a high-functioning alcoholic who maintained jobs in Boston-area journalism. The rehab part is often least exciting, but I appreciated how Knapp characterized it as the tortured end of a love affair.

Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp: An excellent addiction memoir that stands out for its smooth and candid writing. For nearly 20 years, Knapp was a high-functioning alcoholic who maintained jobs in Boston-area journalism. The rehab part is often least exciting, but I appreciated how Knapp characterized it as the tortured end of a love affair. The Trauma Cleaner: One Woman’s Extraordinary Life in Death, Decay and Disaster by Sarah Krasnostein: I guarantee you’ve never read a biography quite like this one. It’s part journalistic exposé and part “love letter”; it’s part true crime and part ordinary life story. It considers gender, mental health, addiction, trauma and death. Simply a terrific read.

The Trauma Cleaner: One Woman’s Extraordinary Life in Death, Decay and Disaster by Sarah Krasnostein: I guarantee you’ve never read a biography quite like this one. It’s part journalistic exposé and part “love letter”; it’s part true crime and part ordinary life story. It considers gender, mental health, addiction, trauma and death. Simply a terrific read. Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood: A memoir of growing up in a highly conservative religious setting, but not Evangelical Christianity as you or I have known it. Her father, a married Catholic priest, is an unforgettable character. This is a poet’s mind sparking at high voltage and taking an ironically innocent delight in dirty and iconoclastic talk.

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood: A memoir of growing up in a highly conservative religious setting, but not Evangelical Christianity as you or I have known it. Her father, a married Catholic priest, is an unforgettable character. This is a poet’s mind sparking at high voltage and taking an ironically innocent delight in dirty and iconoclastic talk. The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen: For two months in 1973, Matthiessen joined a zoologist on a journey from the Nepalese Himalayas to the Tibetan Plateau in hopes of spotting the elusive snow leopard. Recently widowed, Matthiessen put his Buddhist training to work as he pondered impermanence and acceptance. The writing is remarkable.

The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen: For two months in 1973, Matthiessen joined a zoologist on a journey from the Nepalese Himalayas to the Tibetan Plateau in hopes of spotting the elusive snow leopard. Recently widowed, Matthiessen put his Buddhist training to work as he pondered impermanence and acceptance. The writing is remarkable.

Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab by Christine Montross: When she was training to become a doctor, Montross was assigned an older female cadaver, Eve, who taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a poet, as evident in this lyrical, compassionate exploration of working with the dead.

Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab by Christine Montross: When she was training to become a doctor, Montross was assigned an older female cadaver, Eve, who taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a poet, as evident in this lyrical, compassionate exploration of working with the dead. Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell: An excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. Orwell works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week. The matter-of-fact words about poverty and hunger are incisive, while the pen portraits are glistening.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell: An excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. Orwell works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week. The matter-of-fact words about poverty and hunger are incisive, while the pen portraits are glistening. A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter: In 1934, Ritter, an Austrian painter, joined her husband Hermann for a year in Spitsbergen. I was fascinated by the details of Ritter’s daily tasks, but also by how her perspective on the landscape changed. No longer a bleak wilderness, it became a tableau of grandeur. A travel classic worth rediscovering.

A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter: In 1934, Ritter, an Austrian painter, joined her husband Hermann for a year in Spitsbergen. I was fascinated by the details of Ritter’s daily tasks, but also by how her perspective on the landscape changed. No longer a bleak wilderness, it became a tableau of grandeur. A travel classic worth rediscovering. Autumn Across America by Edwin Way Teale: In the late 1940s Teale and his wife set out on a 20,000-mile road trip from Cape Cod on the Atlantic coast to Point Reyes on the Pacific to track the autumn. Teale was an early conservationist. His descriptions of nature are gorgeous, and the scientific explanations are at just the right level for the average reader.

Autumn Across America by Edwin Way Teale: In the late 1940s Teale and his wife set out on a 20,000-mile road trip from Cape Cod on the Atlantic coast to Point Reyes on the Pacific to track the autumn. Teale was an early conservationist. His descriptions of nature are gorgeous, and the scientific explanations are at just the right level for the average reader. The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch: This blew me away. Reading this nonlinear memoir of trauma and addiction, you’re amazed the author is still alive, let alone a thriving writer. The writing is truly dazzling, veering between lyrical stream-of-consciousness and in-your-face informality. The watery metaphors are only part of what make it unforgettable.

The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch: This blew me away. Reading this nonlinear memoir of trauma and addiction, you’re amazed the author is still alive, let alone a thriving writer. The writing is truly dazzling, veering between lyrical stream-of-consciousness and in-your-face informality. The watery metaphors are only part of what make it unforgettable.