Three for Novellas in November: Bythell, Carey and Diop

I started my reading for Novellas in November early with these three review books, one nonfiction and two fiction. They have in common the fact that they are published today –although I believe two were released early to beat the lockdown. Don’t worry, though; there are still plenty of ways of getting hold of new books: most publishers and bookshops are still filling orders, or you can use the UK’s newly launched Bookshop.org site and support your local indie.

Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops by Shaun Bythell

[137 pages]

Cheerfully colored and sized to fit into a Christmas stocking, this is a fun follow-up to Bythell’s accounts of life at The Bookshop in Wigtown, The Diary of a Bookseller and Confessions of a Bookseller. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names as if naming species. When I saw him chat with Lee Randall at the opening event of the Wigtown Book Festival, he introduced a few, such as the autodidact who knows more than you and will tell you all about their pet subject (the Homo odiosus, or bore). This is not the same, though, as the expert who shares genuinely useful knowledge – of a rare cover version on a crime paperback, for instance (Homo utilis, a helpful person).

Cheerfully colored and sized to fit into a Christmas stocking, this is a fun follow-up to Bythell’s accounts of life at The Bookshop in Wigtown, The Diary of a Bookseller and Confessions of a Bookseller. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names as if naming species. When I saw him chat with Lee Randall at the opening event of the Wigtown Book Festival, he introduced a few, such as the autodidact who knows more than you and will tell you all about their pet subject (the Homo odiosus, or bore). This is not the same, though, as the expert who shares genuinely useful knowledge – of a rare cover version on a crime paperback, for instance (Homo utilis, a helpful person).

There’s also the occultists, the erotica browsers, the local historians, the self-published authors, the bearded pensioners (Senex cum barba) holidaying in their caravans, and the young families – now that he has one of his own, he’s become a bit more tolerant. Setting aside the good-natured complaints, who are his favorite customers? Those who revel in the love of books and don’t quibble about the cost. Generally, these are not antiquarian book experts looking for a bargain, but everyday shoppers who keep a low-key collection of fiction or maybe specifically sci-fi and graphic novels, which fly off the shelves for good prices.

So which type am I? Well, occasionally I’m a farter (Crepans), but you won’t hold that against me, will you? I’d like to think I fit squarely into the normal people category (Homines normales) when I visited Wigtown in April 2018: we went in not knowing what we wanted but ended up purchasing a decent stack and even had a pleasant conversation with the man himself at the till – he’s much less of a curmudgeon in person than in his books. I do recommend this to those who have read and loved his other work.

With thanks to Profile Books for the free copy for review.

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey

[160 pages]

Carey’s historical novel Little was one of my highlights of 2018, so I jumped at the chance to read his new book. Interestingly, this riff on the Pinocchio story, narrated by Geppetto from the belly of a giant shark, originally appeared in Italian to accompany an exhibition hosted by the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi at the Parco di Pinocchio in Collodi. Geppetto came from a pottery-painting family but turned to wood when creating a little companion for his loneliness, the wooden boy who astounded him by coming to life. Now a son rather than a mere block of wood, Pinocchio sets off for school but never comes home. When he gets word that a troublesome automaton has been thrown into the sea, Geppetto sets out in a dinghy to find his son but is swallowed by the enormous fish that has been seen off the coast.

Carey’s historical novel Little was one of my highlights of 2018, so I jumped at the chance to read his new book. Interestingly, this riff on the Pinocchio story, narrated by Geppetto from the belly of a giant shark, originally appeared in Italian to accompany an exhibition hosted by the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi at the Parco di Pinocchio in Collodi. Geppetto came from a pottery-painting family but turned to wood when creating a little companion for his loneliness, the wooden boy who astounded him by coming to life. Now a son rather than a mere block of wood, Pinocchio sets off for school but never comes home. When he gets word that a troublesome automaton has been thrown into the sea, Geppetto sets out in a dinghy to find his son but is swallowed by the enormous fish that has been seen off the coast.

The picture of this new world-within-a-world is enthralling. Geppetto finds himself inside a swallowed ship, the Danish schooner Maria. Within the vessel is all he needs to occupy himself, at least for now: wood on which to paint the women he has loved; candle wax and hardtack for sculpting figures. Seaweed to cover his bald spot. Squid ink for his pen so he can write this notebook. A crab that lives in his beard. Relics of the captain’s life to intrigue him.

As a narrator, Geppetto is funny and gifted at wordplay (“This tome is my tomb”; “I unobjected him. Can you object to that?”), yet haunted by his decisions. Carey deftly traces Geppetto’s state of mind as he muses on his loss and imprisonment. The Afterword adds a sly pseudohistorical note to the fantasy. There are black-and-white illustrations throughout, as well as photos of the objects described in the text (and, presumably, featured in the exhibition). For me this didn’t live up to Little, but it would be a great introduction to Carey’s work.

With thanks to Gallic Books for the free copy for review.

At Night All Blood Is Black by David Diop

[145 pages; translated from the French by Anna Moschovakis]

I had no idea that Africans (“Chocolat soldiers”) fought for France in World War I. Diop’s second novel, which has already won several major European prizes, is about two Senegalese brothers-in-arms caught up in trench warfare. Alfa Ndaiye, aged 20, considers Mademba Diop his blood brother or “more-than-brother” (the novel’s French title is “Soul Brother”). From the start we know that Mademba has died. Gravely injured in battle, entrails spilling out, he begged Alfa to end his misery; three times Alfa refused. Having watched his friend die in agony, he knows he did the wrong thing. Slitting the man’s throat would have been the compassionate choice. From now on, Alfa will atone by brutally wreaking Mademba’s method of death on Germans. “The captain’s France needs our savagery, and because we are obedient, myself and the others, we play the savage.” Alas, I thought this bleak exploration of (in)humanity was marred by the repetitive language and unpleasantly sexualized metaphors.

I had no idea that Africans (“Chocolat soldiers”) fought for France in World War I. Diop’s second novel, which has already won several major European prizes, is about two Senegalese brothers-in-arms caught up in trench warfare. Alfa Ndaiye, aged 20, considers Mademba Diop his blood brother or “more-than-brother” (the novel’s French title is “Soul Brother”). From the start we know that Mademba has died. Gravely injured in battle, entrails spilling out, he begged Alfa to end his misery; three times Alfa refused. Having watched his friend die in agony, he knows he did the wrong thing. Slitting the man’s throat would have been the compassionate choice. From now on, Alfa will atone by brutally wreaking Mademba’s method of death on Germans. “The captain’s France needs our savagery, and because we are obedient, myself and the others, we play the savage.” Alas, I thought this bleak exploration of (in)humanity was marred by the repetitive language and unpleasantly sexualized metaphors.

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Do any of these novellas take your fancy?

What November releases can you recommend?

Novellas in November Begins!

Burnt out on doorstoppers after Victober? Wondering how you’ll ever reach your reading target in this strange year? It’s time to stack up the short books (anything under 200 pages) and get reading towards Novellas in November!

Here’s a reminder of the weekly themes Cathy and I are taking it in turn to host:

2–8 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas (Rebecca)

16–22 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

23–29 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

Leave your links here and/or on Cathy’s intro post at 746 Books and we’ll update our blogs through the month to include them. We look forward to seeing what you read!

Don’t forget to tag us on Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and use the hashtag #NovNov.

Novellas in November 2020 posts:

Mrs Caliban by Rachel Ingalls (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson (reviewed by Hopewell’s Library of Life)

Three Novellas – Bythell, Carey and Diop

Mostly Hero by Anna Burns (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Dark Wave by Lana Guineay (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Man from London by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Helen at She Reads Novels)

Cyclone by Vance Palmer (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Short Fiction from Steinbeck and Triolet (reviewed by Carol at cas d’intérêt)

Contemporary Fiction novella recommendations (Monika at Lovely Bookshelf)

Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Surfacing – Margaret Atwood (1973) (reviewed by Ali at Heavenali)

Simenon, Greg & Moss (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

10 Favorite Nonfiction Novellas from My Shelves

The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

300 Arguments by Sarah Manguso (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

The Poisoning by Maria Lazar (reviewed by Juliana at The Blank Garden)

Summerwater by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Invisible Land by Hubert Mingarelli (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Moon Is Down by John Steinbeck (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Two Reviews for Non-fiction Novella Week (Cathy at 746books)

A Month in Siena by Hisham Matar (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Viewing the World)

Our Nig by Harriet E. Wilson (reviewed by Juliana at The Blank Garden)

Runaway Amish Girl: The Great Escape by Emma Gingerich (reviewed by Hopewell’s Library of Life)

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante (reviewed by Radhika’s Reading Retreat)

8 Novellas in Translation (reviewed by Grant at 1streading)

Nonfiction novella recommendations (Monika at Lovely Bookshelf)

Four More Short Nonfiction Books for Novellas for November

Quicksand and Passing by Nella Larsen (reviewed by Davida at The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Bill Bailey’s Remarkable Guide to Happiness (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

The Legend of the Holy Drinker by Joseph Roth (reviewed by Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings)

Chess by Stefan Zweig (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Popcorn by Cornelia Otis Skinner (reviewed by Ali at Heavenali)

The Transmigration of Bodies by Yuri Herrera (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Viewing the World)

The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben (reviewed by Hopewell’s Library of Life)

The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina Rivera Garza (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Three novellas: Albertalli, Meruane, Moore (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

A Meal in Winter by Hubert Mingarelli (reviewed by Karen at Booker Talk)

Wendy McGrath’s Trilogy (reviewed by Marcie at Buried in Print)

Dog Island by Philippe Claudel (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Man behind Narnia by AN Wilson (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Fall on Me by Nigel Featherstone (reviewed by Nancy at NancyElin)

An interview with Cath Barton, author of novella The Plankton Collector, by Kathryn at Nut Press

Black Water by Joyce Carol Oates (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Translated novella recommendations (Monika at Lovely Bookshelf)

Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzberg (reviewed by Jacqui at JacquiWine’s Journal)

Dolores by Lauren Aimee Curtis (reviewed by Nancy at NancyElin)

The Provincial Lady Goes Further by E.M. Delafield (reviewed by Hopewell’s Library of Life)

The Pigeon by Patrick Süskind (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

A Girl Returned by Donatella Di Pietrantonio (reviewed by Ali at Heavenali)

Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Icefall by Stephanie Gunn (reviewed by Nancy at NancyElin)

Maigret and the Reluctant Witnesses by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

The Silence by Don DeLillo (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

My favourite classic novellas (Cathy at 746books)

Short Classics recommendations (Monika at Lovely Bookshelf)

Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Viewing the World)

Cheerful Weather for the Wedding by Julia Strachey (reviewed by Radhika’s Reading Retreat)

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (reviewed by Brona’s Books)

The Jew’s Beech-Tree by Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (reviewed by Juliana at The Blank Garden)

Daughters by Lucy Fricke (reviewed by Lizzy’s Literary Life)

What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

The Mystery of the Enchanted Crypt by Eduardo Mendoza (reviewed by Reese Warner)

The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

In the Sweep of the Bay by Cath Barton (reviewed by Calmgrove)

Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks (reviewed by Juliana at The Blank Garden)

Short Classics: Orwell + Austen, Buchan, Capote, Wharton (Margaret at BooksPlease)

Follies and The Power of Privilege (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Strange Bird by Jeff Vandermeer (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Girl Reporter by Tansy Roberts (reviewed by Nancy at NancyElin)

The House of Dolls by Barbara Comyns (reviewed by Ali at Heavenali)

Elizabeth and Her German Garden by Elizabeth Von Arnim (reviewed by Brona’s Books)

Simpson Returns by Wayne Macauley (reviewed by Nancy at NancyElin)

Miscellaneous Novellas: Murdoch, Read & Spark; Comics; Art Books

Three short classics from the 746: Mann, West, Atwood (reviewed by Cathy at 746books)

Writers on Writers: Josephine Rowe on Beverley Farmer (reviewed by Brona’s Books)

Utz by Bruce Chatwin (reviewed by Calmgrove)

A Novellas Inventory (Market Garden Reader)

Three novellas by Ivan Turgenev (reviewed by Book Around the Corner)

The Lifted Veil & Silly Novels by Lady Novelists by George Eliot (reviewed by Helen at She Reads Novels)

The Weight of Things by Marianne Fritz (reviewed by J. C. Greenway at 10 million hardbacks)

Theo by Paul Torday (reviewed by Davida at The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Another novella by Triolet (reviewed by Carol at cas d’intérêt)

The Three Graces of Va-Kill by

Miscellaneous novellas: Oates, Moss, Orstavik, de Moor, Hull (reviewed by Naomi at Consumed by Ink)

See also this terrific list of Australian novellas put together by Brona, a list of 17 intriguing novellas you can read in a day (or an afternoon) put together by Kim, and Louise Walter’s thoughts on the writing (and publishing) of novellas.

November Plans: Novellas, Margaret Atwood Reading Month & More

My big thing next month will, of course, be Novellas in November, which I’m co-hosting with Cathy of 746 Books as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts. I’m taking the lead on two alternating weeks and will introduce them with mini-reviews of some of my favorite short books from these categories:

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas

23–29 November: Short classics

I’m also using this as an excuse to get back into the nine books of under 200 pages that have ended up on my “Set Aside Temporarily” shelf. I swore after last year that I would break myself of the bad habit of letting books linger like this, but it has continued in 2020.

Other November reading plans…

Readalong of Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature

I learned about this book through Losing Eden by Lucy Jones; she mentions it in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Jarman found solace in his Dungeness, Kent garden while dying of AIDS. Shortly after I came across that reference, I learned that his home, Prospect Cottage, had just been rescued from private sale by a crowdfunding campaign. I hope to visit it someday. In the meantime, Creative Folkestone is hosting an Autumn Reads festival on his journal, Modern Nature, running from the 19th to 22nd. I’ve already begun reading it to get a headstart. Do you have a copy? If so, join in!

I learned about this book through Losing Eden by Lucy Jones; she mentions it in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Jarman found solace in his Dungeness, Kent garden while dying of AIDS. Shortly after I came across that reference, I learned that his home, Prospect Cottage, had just been rescued from private sale by a crowdfunding campaign. I hope to visit it someday. In the meantime, Creative Folkestone is hosting an Autumn Reads festival on his journal, Modern Nature, running from the 19th to 22nd. I’ve already begun reading it to get a headstart. Do you have a copy? If so, join in!

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

This is the third year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. (Check out the neat bingo card they made this year!) I plan to read the short story volume Wilderness Tips and her new poetry collection, Dearly,on the way for me to review for Shiny New Books. If I fancy adding anything else in, there are tons of her books to choose from across the holdings of the public and university libraries.

This is the third year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. (Check out the neat bingo card they made this year!) I plan to read the short story volume Wilderness Tips and her new poetry collection, Dearly,on the way for me to review for Shiny New Books. If I fancy adding anything else in, there are tons of her books to choose from across the holdings of the public and university libraries.

Nonfiction November

I don’t usually participate in this challenge because nonfiction makes up at least 40% of my reading anyway, but the past couple of years I enjoyed putting together fiction and nonfiction pairings and “Being the Expert” on women’s religious memoirs. I might end up doing at least one post, especially as I have some “Three on a Theme” posts in mind to encompass a couple of nonfiction topics I happen to have read several books about. The full schedule is here.

Young Writer of the Year Award

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I look forward to following along with the nominated books, as I did last year, and attending the virtual prize ceremony. With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist of four. Fingers crossed for Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Naoise Dolan, Jessica J. Lee, Olivia Potts and Nina Mingya Powles; Niamh Campbell, Catherine Cho, Tiffany Francis and Emma Glass are a few other possibilities. (By chance, only young women are on my radar this year!)

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I look forward to following along with the nominated books, as I did last year, and attending the virtual prize ceremony. With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist of four. Fingers crossed for Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Naoise Dolan, Jessica J. Lee, Olivia Potts and Nina Mingya Powles; Niamh Campbell, Catherine Cho, Tiffany Francis and Emma Glass are a few other possibilities. (By chance, only young women are on my radar this year!)

November is such a busy month for book blogging: it’s also Australia Reading Month and German Literature Month. I don’t happen to have any books on the pile that will fit these prompts, but you might like to think about how you can combine one of them with some of the other challenges out there!

Any reading plans for November? Will you be joining in with novellas, Margaret Atwood’s books or Nonfiction November?

Autumn Reading: The Pumpkin Eater and More

I’ve been gearing up for Novellas in November with a few short autumnal reads, as well as some picture books bedecked with fallen leaves, pumpkins and warm scarves.

An Event in Autumn by Henning Mankell (2004)

[Translated from the Swedish by Laurie Thompson, 2014]

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

Of course things aren’t going to go smoothly with this venture. You have to suspend disbelief when reading about the adventures of investigators; it’s like they attract corpses. So it’s not much of a surprise that while he’s walking the grounds of this house he finds a human hand poking out of the soil, and eventually the remains of a middle-aged couple are unearthed. The rest of the book is about finding out what happened on the property at the time of the Second World War. Wallander says he doesn’t believe in ghosts, but victims of wrongful death are as persistent as ghosts: they won’t be ignored until answers are found.

This was a quick and easy read, but nothing about it (setting, topics, characterization, prose) made me inclined to read further in the author’s work.

My rating:

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer (1962)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, they’re building a glass tower as their countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood.

An excellent 2011 introduction by Daphne Merkin reveals how autobiographical this seventh novel was for Mortimer. But her backstory isn’t a necessary prerequisite for appreciating this razor-sharp period piece. You get a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility and chafing at the thought that she’s had no choice in what life has dealt her. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humor and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind. I was reminded of Janice Galloway’s The Trick Is to Keep Breathing and Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. If you’re still looking for ideas for Novellas in November, I recommend it highly.

My rating:

Snow in Autumn by Irène Némirovsky (1931)

[Translated from the French by Sandra Smith, 2007]

(Classic of the Month, #2)

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

My rating:

Plus a quartet of children’s picture books from the library:

Pumpkin Soup by Helen Cooper: A cat, a squirrel and a duck live together in a teapot-shaped cabin in the woods. They cook pumpkin soup and make music in perfect harmony, each cheerfully playing their assigned role, until the day Duck decides he wants to be the one to stir the soup. A vicious quarrel ensues, and Duck leaves. Nothing is the same without the whole trio there. After some misadventures, when the gang is finally back together, they’ve learned their lesson about flexibility … or have they? Adorably mischievous.

Moomin and the Golden Leaf by Richard Dungworth: Beware: this is not actually a Tove Jansson plot, although her name is, misleadingly, printed on the cover (under tiny letters “Based on the original stories by…”). Autumn has come to Moominvalley. Moomin and Sniff find a golden leaf while they’re out foraging. He sets out to find the golden tree it must have come from, but the source is not what he expected. Meanwhile, the rest are rehearsing a play to perform at the Autumn Ball before a seasonal feast. This was rather twee and didn’t capture Jansson’s playful, slightly melancholy charm.

Little Owl’s Orange Scarf by Tatyana Feeney: Ungrateful Little Owl thinks the orange scarf his mother knit for him is too scratchy. He tries “very hard to lose his new scarf” and finally manages it on a trip to the zoo. His mother lets him choose his replacement wool, a soft green. I liked the color blocks and the simple design, and the final reveal of what happened to the orange scarf is cute, but I’m not sure the message is one to support (pickiness vs. making do with what you have).

Christopher Pumpkin by Sue Hendra and Paul Linnet: The witch of Spooksville needs help preparing for a big party, so brings a set of pumpkins to life. Something goes a bit wrong with the last one, though: instead of all things ghoulish, Christopher Pumpkin loves all things fun. He bakes cupcakes instead of stirring gross potions and strums a blue ukulele instead of inducing screams. The witch threatens to turn Chris into soup if he can’t be scary. The plan he comes up with is the icing on the cake of a sweet, funny book delivered in rhyming couplets. Good for helping kids think about stereotypes and how we treat those who don’t fit in.

Have you read any autumn-appropriate books lately?

Announcing Novellas in November!

Lots of us make a habit of prioritizing novellas in our November reading. (Who can resist that alliteration?) Perhaps you’ve been finding it hard to focus on books with all the bad news around, and your reading target for the year is looking out of reach. If you’re beset by distractions or only have brief bits of free time in your day, short books can be a boon.

In 2018 Laura Frey surveyed the history of Novellas in November, which has had various incarnations but no particular host. This year Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting it as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts. We’ll both put up an opening post on 1 November where you can leave your links throughout the month, to be rounded up on the 30th, and we’ll take turns introducing a theme each Monday.

The definition of a novella is loose – it’s based on word count rather than number of pages – but we suggest aiming for 150 pages or under, with a firm upper limit of 200 pages. Any genre is valid. As author Joe Hill (the son of Stephen King) has said, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” With distinctive characters, intense scenes and sharp storytelling, the best novellas can draw you in for a memorable reading experience – maybe even in one sitting.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Australia Reading Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that count towards multiple challenges? See Cathy’s recent post for ideas of how books can overlap on a few categories. Or you might choose a short Atwood novel, like Surfacing (186 pages) or The Penelopiad (199 pages).

2–8 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas (Rebecca)

16–22 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

23–29 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

We’re looking forward to having you join us! Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and the hashtag #NovNov.

My stacks of possibilities for the four weeks (with a library haul of mostly lit in translation to follow).

Bonus points for three of the below being November review books!

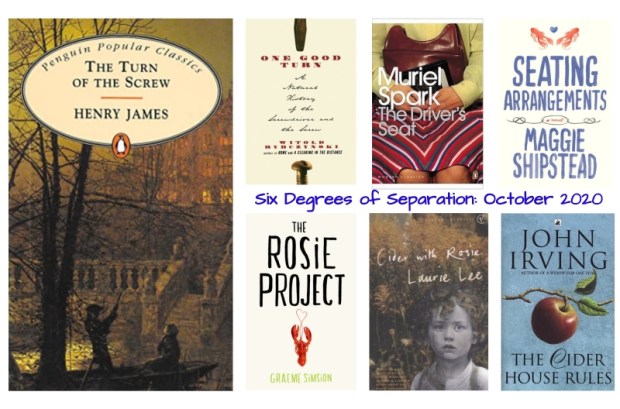

Six Degrees of Separation: From The Turn of the Screw to The Cider House Rules

This month we’re starting with The Turn of the Screw, a Gothic horror novella about a governess and her charges – and one of only two Henry James novels I’ve read (the other is What Maisie Knew; I’ve gravitated towards the short, atypical ones, and even in those his style is barely readable). Most of my links are based on title words this time, along with a pair of cover images.

#1 On our trip to Hay-on-Wye last month, I was amused to see in a shop a book called One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw (2000) by Witold Rybczynski. A bit of a niche subject and nothing I can ever imagine myself reading, but it’s somehow pleasing to know that it exists.

#2 I’m keen to try Muriel Spark again with The Driver’s Seat (1970), a suspense novella with a seam of dark comedy. I remember reading a review of it on Heaven Ali’s blog and thinking that it sounded deliciously creepy. My plan is to get it out from the university library to read and review for Novellas in November.

#3 Seating Arrangements by Maggie Shipstead was one of my favorite debut novels of 2012. An upper-middle-class family prepares for their heavily pregnant daughter’s wedding weekend on an island off Connecticut. Shipstead is great at capturing social interactions. There’s pathos plus humor here; I particularly liked the exploding whale carcass. I’m still waiting for her to come out with a worthy follow-up (2014’s Astonish Me was so-so).

#4 The cover lobsters take me to The Rosie Project (2013) by Graeme Simsion, the first and best book in his Don Tillman trilogy. A (probably autistic) Melbourne genetics professor, Don decides at age 39 that it is time to find a wife. He goes about it in a typically methodical manner, drawing up a 16-page questionnaire, but still falls in love with the ‘wrong’ woman.

#5 Earlier in the year I reviewed Cider with Rosie (1959) by Laurie Lee as my classic of the month and a food-themed entry in my 20 Books of Summer. It’s a nostalgic, evocative look at a country childhood. The title comes from a late moment when Rosie Burdock tempts the adolescent Lee with alcoholic cider and kisses underneath a hay wagon.

#6 My current reread is The Cider House Rules (1985), one of my favorite John Irving novels. Homer Wells is the one kid at the St. Cloud’s, Maine orphanage who never got adopted. Instead, he assists the director, Dr. Wilbur Larch, and later runs a cider factory. Expect a review in a few weeks – this will count as my Doorstopper of the Month.

Going from spooky happenings to apple cider, my chain feels on-brand for October!

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best. Her introductory post is here.) Next month is a wildcard: start with a book you’ve ended a previous chain with.

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

The Bitch by Pilar Quintana: Blog Tour and #WITMonth 2020, Part I

My first selection for Women in Translation Month is an intense Colombian novella originally published in 2017 and translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman. The Bitch, which won the Colombian Biblioteca de Narrativa Prize and has been preserved in a time capsule in Bogotá, is Pilar Quintana’s first book to become available in English translation.

The title is literal, yet its harshness is deliberate: It’s clear from the first scene onwards that this is no cosy tale for animal lovers. Doña Elodia, who runs a beachfront restaurant, has just found her dog dead on the sand, killed either accidentally or intentionally by rat poison. Just six days before, the dog had given birth to 10 puppies. Damaris agrees to adopt a grey female from the litter. Her husband Rogelio already keeps three guard dogs at their shantytown shack and is mean to them, but Damaris is determined things will be different with this pup.

Damaris seems to be cursed, though: she’s still haunted by the death by drowning of a neighbour boy, Nicolasito Reyes, who didn’t heed her warning about the dangerous rocks and waves; she lost her mother to a stray bullet when she was 14; and despite trying many herbs and potions she and Rogelio have not been able to have children. Tenderness has ebbed and flowed in her marriage; “She was over forty now, the age women dry up.” Her cousin disapproves of the attention she lavishes on the puppy, Chirli – the name she would have given a daughter.

Chirli doesn’t repay Damaris’ love with the devotion she expects. She’d been hoping for a faithful companion during her work as a caretaker and cleaner at the big houses on the bluff, but Chirli keeps running off – once disappearing for 33 days – and coming back pregnant. The dog serves as a symbol of parts of herself she doesn’t want to acknowledge, and desires she has repressed. This dark story of guilt and betrayal set at the edge of a menacing jungle can be interpreted at face value or as an allegory – the latter was the only way I could accept.

I appreciated the endnotes about the book design. The terrific cover photograph by Felipe Manorov Gomes was taken on a Brazilian beach. The stray’s world-weary expression is perfect.

The Bitch is published by World Editions on the 20th of August. I was delighted to be asked to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Are you doing any special reading for Women in Translation month this year?

Some Books about Marriage

My pre-Valentine’s Day reading involved a lot of books with “love”, “heart”, “romance”, etc. in the title (here’s the post that resulted). I ended up with a number of leftovers, plus some incidental reads from late in 2019, that focused on marriage – whether it’s happy or troubled, or not technically a marriage at all.

Marriage: A Duet by Anne Taylor Fleming (2003)

Two novellas in one volume. In “A Married Woman,” Caroline Betts’s husband, William, is in a coma after a stroke or heart attack. As she and her adult children visit him in the hospital and ponder the decision they will have to make, she remains haunted by the affair William had with one of their daughter’s friends 15 years ago. Although at the time it seemed to destroy their marriage, she stayed and they built a new relationship.

Two novellas in one volume. In “A Married Woman,” Caroline Betts’s husband, William, is in a coma after a stroke or heart attack. As she and her adult children visit him in the hospital and ponder the decision they will have to make, she remains haunted by the affair William had with one of their daughter’s friends 15 years ago. Although at the time it seemed to destroy their marriage, she stayed and they built a new relationship.

I fully expected the second novella, “A Married Man,” to give William’s perspective (like in Carol Shields’s Happenstance), but instead it’s a separate story with different characters, though still set in California c. 2000. Here the dynamic is flipped: it’s the wife who had an affair and the husband who has to try to come to terms with it. David and Marcia Sanderson start marriage therapy at New Beginnings and, with the help of Prozac and Viagra, David hopes to get past his bitterness and give in to his wife’s romantic overtures.

Fleming is a careful observer of how marriages change over time and in response to shocks, but overall I found the tone of these tales abrasive and the language slightly raunchy.

Not quite about a marriage, but a relationship so lovely that I can’t resist including it…

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf (2015)

Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. I’d long meant to try Kent Haruf’s work and even had the first two Plainsong trilogy books on the shelf, but this novella, picked up secondhand at a bargain price from a charity warehouse, demanded to be read first. Fans of Elizabeth Strout’s work will find in Haruf’s Holt, Colorado an echo of her Crosby, Maine – fictional towns where ordinary folk live out their quiet triumphs and sorrows. From the first line, which opens in medias res, Haruf draws you in, making you feel as if you’ve known these characters forever: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” She has a proposal for her neighbor. She’s a widow; he’s a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to melancholy thoughts about how they could have done better by their families (“life hasn’t turned out right for either of us, not the way we expected,” Louis says). Would he like to come over to her house at nights to talk and sleep? Just two ageing creatures huddling together for comfort; no hanky-panky expected or desired.

Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. I’d long meant to try Kent Haruf’s work and even had the first two Plainsong trilogy books on the shelf, but this novella, picked up secondhand at a bargain price from a charity warehouse, demanded to be read first. Fans of Elizabeth Strout’s work will find in Haruf’s Holt, Colorado an echo of her Crosby, Maine – fictional towns where ordinary folk live out their quiet triumphs and sorrows. From the first line, which opens in medias res, Haruf draws you in, making you feel as if you’ve known these characters forever: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” She has a proposal for her neighbor. She’s a widow; he’s a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to melancholy thoughts about how they could have done better by their families (“life hasn’t turned out right for either of us, not the way we expected,” Louis says). Would he like to come over to her house at nights to talk and sleep? Just two ageing creatures huddling together for comfort; no hanky-panky expected or desired.

So that’s just what they do. Before long, though, they come up against the disapproval of locals and family, especially when Addie’s grandson comes to stay and they join Louis to make a makeshift trio. The matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion in this story about the everyday miracle of human connection. There’s even a neat little reference to Haruf’s Benediction at the start of Chapter 34 (again like Strout, who peppered Olive, Again with cameo appearances from characters introduced in her earlier books). I also loved that the characters live on Cedar Street – I grew up on a Cedar Street. This gets my highest recommendation.

State of the Union: A Marriage in Ten Parts by Nick Hornby (2019)

Hornby has been making quite a name for himself in film and television. State of the Union is also a TV series, and reads a lot like a script because it’s composed mostly of the dialogue between Tom and Louise, an estranged couple who each week meet up for a drink in the pub before their marriage counseling appointment. There’s very little descriptive writing, and much of the time Hornby doesn’t even need to add speech attributions because it’s clear who’s saying what in the back and forth.

Hornby has been making quite a name for himself in film and television. State of the Union is also a TV series, and reads a lot like a script because it’s composed mostly of the dialogue between Tom and Louise, an estranged couple who each week meet up for a drink in the pub before their marriage counseling appointment. There’s very little descriptive writing, and much of the time Hornby doesn’t even need to add speech attributions because it’s clear who’s saying what in the back and forth.

The crisis in this marriage was precipitated by Louise, a gerontologist, sleeping with someone else after her sex life with Tom, an underemployed music writer, dried up. They rehash their life together, what went wrong, and what might happen next in 10 snappy chapters that are funny but also cut close to the bone. What married person hasn’t wondered where the magic went as midlife approaches? (Tom: “I hate to be unromantic, but convenient placement is pretty much the definition of marital sex.”)

Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage by Madeleine L’Engle (1988)

The fourth and final volume of the autobiographical Crosswicks Journal. This one focuses on L’Engle’s 40-year marriage to Hugh Franklin, an actor best known for his role as Dr. Charles Tyler in All My Children between 1970 and 1983. In the book’s present day, the summer of 1986, she’s worried about Hugh when his bladder cancer, which starts off seeming treatable, leads to every possible complication and deterioration. Her days are divided between home, work (speaking engagements; teaching workshops at a writers’ conference) and the hospital.

The fourth and final volume of the autobiographical Crosswicks Journal. This one focuses on L’Engle’s 40-year marriage to Hugh Franklin, an actor best known for his role as Dr. Charles Tyler in All My Children between 1970 and 1983. In the book’s present day, the summer of 1986, she’s worried about Hugh when his bladder cancer, which starts off seeming treatable, leads to every possible complication and deterioration. Her days are divided between home, work (speaking engagements; teaching workshops at a writers’ conference) and the hospital.

Drifting between past and present, she remembers how she and Hugh met in the 1940s NYC theatre world, their early years of marriage, becoming parents to Josephine and Bion and then, when close friends died suddenly, adopting their goddaughter, and taking on the adventure of renovating Crosswicks farmhouse in Connecticut and temporarily running the local general store. As usual, L’Engle writes beautifully about having faith in a time of uncertainty. (The title refers not just to marriage, but also to Bach pieces that she, a devoted amateur piano player, used for practice.)

A wonderful passage about marriage:

“Our love has been anything but perfect and anything but static. Inevitably there have been times when one of us has outrun the other and has had to wait patiently for the other to catch up. There have been times when we have misunderstood each other, demanded too much of each other, been insensitive to the other’s needs. I do not believe there is any marriage where this does not happen. The growth of love is not a straight line, but a series of hills and valleys. I suspect that in every good marriage there are times when love seems to be over. Sometimes these desert lines are simply the only way to the next oasis, which is far more lush and beautiful after the desert crossing than it could possibly have been without it.”

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer (2003)

My latest book club read. On a flight to Finland, where her supposed genius writer of a husband, Joe Castleman, will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. When she first met Joe in 1956, she was a student at Smith College and he was her (married) creative writing professor, even though he’d only had a couple of stories published in middling literary magazines. Joan was a promising author in her own right, but when Joe left his first wife for her and she dropped out of college, she willingly took up a supporting role instead, and has remained in it for decades.

My latest book club read. On a flight to Finland, where her supposed genius writer of a husband, Joe Castleman, will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. When she first met Joe in 1956, she was a student at Smith College and he was her (married) creative writing professor, even though he’d only had a couple of stories published in middling literary magazines. Joan was a promising author in her own right, but when Joe left his first wife for her and she dropped out of college, she willingly took up a supporting role instead, and has remained in it for decades.

Ever since his first novel, The Walnut, a thinly veiled account of leaving Carol for Joan, Joe has produced books “populated by unhappy, unfaithful American husbands and their complicated wives.” Add on the fact that he’s Jewish and you have a Saul Bellow or Philip Roth type, a serial womanizer who’s publicly uxorious.

Alternating between the trip to Helsinki and telling scenes from earlier in their marriage, this short novel is deceptively profound. The setup may feel familiar, but Joan’s narration is bitingly funny and the points about the greater value attributed to men’s work are still valid. There’s also a juicy twist I never saw coming, as Joan decides what role she wants to play in perpetuating Joe’s literary legacy. My second by Wolitzer; I’ll certainly read more.

Plus a DNF:

The Story of a Marriage by Andrew Sean Greer (2008)

In 1953 in San Francisco, Pearlie Cook learns two major secrets about her husband Holland after his old friend shows up at their door. Greer tries to present another fact about the married couple as a big surprise, but had planted so many clues, starting on page 9, that I’d already guessed it and wasn’t shocked at the end of Part I as I was supposed to be. Greer writes perfectly capably, but I wasn’t able to connect with this one and didn’t love Less as much as most people did. I don’t think I’ll be trying another of his books. (I read 93 pages out of 195.)

In 1953 in San Francisco, Pearlie Cook learns two major secrets about her husband Holland after his old friend shows up at their door. Greer tries to present another fact about the married couple as a big surprise, but had planted so many clues, starting on page 9, that I’d already guessed it and wasn’t shocked at the end of Part I as I was supposed to be. Greer writes perfectly capably, but I wasn’t able to connect with this one and didn’t love Less as much as most people did. I don’t think I’ll be trying another of his books. (I read 93 pages out of 195.)

Have you read any books about marriage recently?

Love, Etc. – Some Thematic Reading for Valentine’s Day

Even though we aren’t big on Valentine’s Day (we went out to a “Flavours of Africa” supper club last weekend and are calling it our celebration meal), for the past three years I’ve ended up doing themed posts featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title or that consider romantic or familial love in some way. (Here are my 2017, 2018 and 2019 posts.) These seven selections, all of them fiction, sometimes end up being more bittersweet or ironic than straightforwardly romantic, but see what catches your eye anyway.

Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler (2014)

Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin; four weddings (no funeral – though there are a couple of close calls along the way). Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? Henry is the family man, a dairy farmer who married his college sweetheart, Beth. Lee* is a musician, the closest thing to a rock star Little Wing will ever produce. He became famous for Shotgun Lovesongs, a bestselling album he recorded by himself in a refurbished chicken coop for $600, and now lives in New York City and hobnobs with celebrities. Kip gave up being a Chicago commodities trader to return to Little Wing and spruce up the old mill into an events venue. Ronny lived for alcohol and rodeos until a drunken accident ended his career and damaged his brain.

Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin; four weddings (no funeral – though there are a couple of close calls along the way). Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? Henry is the family man, a dairy farmer who married his college sweetheart, Beth. Lee* is a musician, the closest thing to a rock star Little Wing will ever produce. He became famous for Shotgun Lovesongs, a bestselling album he recorded by himself in a refurbished chicken coop for $600, and now lives in New York City and hobnobs with celebrities. Kip gave up being a Chicago commodities trader to return to Little Wing and spruce up the old mill into an events venue. Ronny lived for alcohol and rodeos until a drunken accident ended his career and damaged his brain.

The friends have their fair share of petty quarrels and everyday crises, but the big one hits when one guy confesses to another that he’s in love with his wife. Male friendship still feels like a rarer subject for fiction, but you don’t have to fear any macho stylings here. The narration rotates between the four men, but Beth also has a couple of sections, including the longest one in the book. This is full of nostalgia and small-town (especially winter) atmosphere, but also brimming with the sort of emotion that gets a knot started in the top of your throat. All the characters are wondering whether they’ve made the right decisions. There are a lot of bittersweet moments, but also some comic ones. The entire pickled egg sequence, for instance, is a riot even as it skirts the edge of tragedy.

*Apparently based on Bon Iver (Justin Vernon), whose first album was a similarly low-budget phenomenon recorded in Wisconsin. I’d never heard any Bon Iver before and expected something like the more lo-fi guy-with-guitar tracks on the Garden State soundtrack. My husband has a copy of the band’s 2011 self-titled album, so I listened to that and found that it has a very different sound: expansive, trance-like, lots of horns and strings. (But NB, the final track is called “Beth/Rest.”) For something more akin to what Lee might play, try this video.

Mr Loverman by Bernardine Evaristo (2013)

Barry came to London from Antigua and has been married for 50 years to Carmel, the mother of his two adult daughters. For years Carmel has been fed up with his drinking and gallivanting, assuming he has lots of women on the side. Little does she know that Barry’s best friend, Morris, has also been his lover for 60 years. Morris divorced his own wife long ago, and he’s keen for Barry to leave Carmel and set up home with him, maybe even get a civil partnership. When Carmel goes back to Antigua for her father’s funeral, it’s Barry’s last chance to live it up as a bachelor and pluck up his courage to tell his wife the truth.

Barry came to London from Antigua and has been married for 50 years to Carmel, the mother of his two adult daughters. For years Carmel has been fed up with his drinking and gallivanting, assuming he has lots of women on the side. Little does she know that Barry’s best friend, Morris, has also been his lover for 60 years. Morris divorced his own wife long ago, and he’s keen for Barry to leave Carmel and set up home with him, maybe even get a civil partnership. When Carmel goes back to Antigua for her father’s funeral, it’s Barry’s last chance to live it up as a bachelor and pluck up his courage to tell his wife the truth.

Barry’s voice is a delight: a funny mixture of patois and formality; slang and Shakespeare quotes. Cleverly, Evaristo avoids turning Carmel into a mute victim by giving her occasional chapters of her own (“Song of…” versus Barry’s “The Art of…” chapters), written in the second person and in the hybrid poetry style readers of Girl, Woman, Other will recognize. From these sections we learn that Carmel has her own secrets and an equal determination to live a more authentic life. Although it’s sad that these two characters have spent so long deceiving each other and themselves, this is an essentially comic novel that pokes fun at traditional mores and includes several glittering portraits.

Mariette in Ecstasy by Ron Hansen (1991)

Set in an upstate New York convent mostly in 1906–7, this is a story of religious fervor, doubt and jealousy. Mariette Baptiste is a 17-year-old postulant; her (literal) sister, 20 years older, is the prioress here. Mariette is given to mystical swoons and, just after the Christmas mass, also develops the stigmata. Her fellow nuns are divided: some think Mariette is a saint who is bringing honor to their organization; others believe she has fabricated her calling and is vain enough to have inflicted the stigmata on herself. A priest and a doctor both examine her, but ultimately it’s for the sisters to decide whether they are housing a miracle or a fraud.

Set in an upstate New York convent mostly in 1906–7, this is a story of religious fervor, doubt and jealousy. Mariette Baptiste is a 17-year-old postulant; her (literal) sister, 20 years older, is the prioress here. Mariette is given to mystical swoons and, just after the Christmas mass, also develops the stigmata. Her fellow nuns are divided: some think Mariette is a saint who is bringing honor to their organization; others believe she has fabricated her calling and is vain enough to have inflicted the stigmata on herself. A priest and a doctor both examine her, but ultimately it’s for the sisters to decide whether they are housing a miracle or a fraud.

The short sections are headed by the names of feasts or saints’ days, and often open with choppy descriptive phrases that didn’t strike me as quite right for the time period (versus Hansen has also written a Western, in which such language would seem appropriate). Although the novella is slow to take off – the stigmata don’t arrive until after the halfway point – it’s a compelling study of the psychology of a religious body, including fragments from others’ testimonies for or against Mariette. I could imagine it working well as a play.

Bizarre Romance by Audrey Niffenegger and Eddie Campbell (2018)

Most of these pieces originated as text-only stories by Niffenegger and were later adapted into comics by Campbell. By the time they got married, they had been collaborating long-distance for a while. Some of the stories incorporate fairies, monsters, ghosts and other worlds. A young woman on her way to a holiday party travels via a mirror to another land where she is queen; a hapless bar fly trades one fairy mistress for another; Arthur Conan Doyle’s father sketches fairies in an asylum; a middle-aged woman on a cruise decides to donate her remaining years to her aged father.

Most of these pieces originated as text-only stories by Niffenegger and were later adapted into comics by Campbell. By the time they got married, they had been collaborating long-distance for a while. Some of the stories incorporate fairies, monsters, ghosts and other worlds. A young woman on her way to a holiday party travels via a mirror to another land where she is queen; a hapless bar fly trades one fairy mistress for another; Arthur Conan Doyle’s father sketches fairies in an asylum; a middle-aged woman on a cruise decides to donate her remaining years to her aged father.

My favorite of the fantastical ones was “Jakob Wywialowski and the Angels,” a story of a man dealing with an angel infestation in the attic; it first appeared as a holiday story on the Amazon homepage in 2003 and is the oldest piece here, with the newest dating from 2015. I also liked “Thursdays, Six to Eight p.m.,” in which a man goes to great lengths to assure two hours of completely uninterrupted reading per week. Strangely, my two favorite pieces were the nonfiction ones: “Digging up the Cat,” about burying her frozen pet with its deceased sibling; and “The Church of the Funnies,” a secular sermon about her history with Catholicism and art that Niffenegger delivered at Manchester Cathedral as part of the 2014 Manchester Literary Festival.

The Nine-Chambered Heart by Janice Pariat (2017)

I find second-person narration intriguing, and I like the idea of various people’s memories of a character being combined to create a composite portrait (previous books that do this that I have enjoyed are The Life and Death of Sophie Stark and Kitchens of the Great Midwest). The protagonist here, never named, is a young Indian writer who travels widely, everywhere from the Himalayas to Tuscany. She also studies and then works in London, where she meets and marries a fellow foreigner. We get the sense that she is restless, eager for adventure and novelty: “You seem to be a woman to whom something is always about to happen.”

I find second-person narration intriguing, and I like the idea of various people’s memories of a character being combined to create a composite portrait (previous books that do this that I have enjoyed are The Life and Death of Sophie Stark and Kitchens of the Great Midwest). The protagonist here, never named, is a young Indian writer who travels widely, everywhere from the Himalayas to Tuscany. She also studies and then works in London, where she meets and marries a fellow foreigner. We get the sense that she is restless, eager for adventure and novelty: “You seem to be a woman to whom something is always about to happen.”

An issue with the book is that most of the nine viewpoints belong to her lovers, which would account for the title but makes their sections seem repetitive. By contrast, I most enjoyed the first chapter, by her art teacher, because it gives us the earliest account of her (at age 12) and so contributes to a more rounded picture of her as opposed to just the impulsive, flirtatious twentysomething hooking up on holidays and at a writers’ residency. I also wish Pariat had further explored the main character’s relationship with her parents. Still, I found this thoroughly absorbing and read it in a few days, steaming through over 100 pages on one.

Kinds of Love by May Sarton (1970)

Christina and Cornelius Chapman have been “summer people,” visiting Willard, New Hampshire each summer for decades, but in the town’s bicentennial year they decide to commit to it full-time. They are seen as incomers by the tough mountain people, but Cornelius’s stroke and their adjustments to his disability and older age have given them the resilience to make it through a hard winter. Sarton lovingly builds up pictures of the townsfolk: Ellen Comstock, Christina’s gruff friend; Nick, Ellen’s mentally troubled son, who’s committed to protecting the local flora and fauna; Jane Tuttle, an ancient botanist; and so on. Willard is clearly a version of Sarton’s beloved Nelson, NH. She’s exploring love for the land as well as love between romantic partners and within families.

Christina and Cornelius Chapman have been “summer people,” visiting Willard, New Hampshire each summer for decades, but in the town’s bicentennial year they decide to commit to it full-time. They are seen as incomers by the tough mountain people, but Cornelius’s stroke and their adjustments to his disability and older age have given them the resilience to make it through a hard winter. Sarton lovingly builds up pictures of the townsfolk: Ellen Comstock, Christina’s gruff friend; Nick, Ellen’s mentally troubled son, who’s committed to protecting the local flora and fauna; Jane Tuttle, an ancient botanist; and so on. Willard is clearly a version of Sarton’s beloved Nelson, NH. She’s exploring love for the land as well as love between romantic partners and within families.

It’s a meandering novel pleasant for its atmosphere and its working out of philosophies of life through conversation and rumination, but Part Three, “A Stranger Comes to Willard,” feels like a misstep. A college dropout turns up at Ellen’s door after his car turns over in a blizzard. Before he’s drafted into the Vietnam War, he has time to fall in love with Christina’s 15-year-old granddaughter, Cathy. There may only be a few years between the teens, but this still didn’t sit well with me.

I liked how each third-person omniscient chapter ends with a passage from Christina’s journal, making things personal and echoing the sort of self-reflective writing for which Sarton became most famous. The book could have been closer to 300 pages instead of over 460, though.

The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall (2019)

An elegant debut novel about two couples thrown together in 1960s New York City when the men are hired as co-pastors of a floundering Presbyterian church. Nearly the first half is devoted to the four main characters’ backstories and how each couple met. It’s a slow, subtle, quiet story (so much so that I only read the first half and skimmed the second), and I kept getting Charles and James, and Lily and Nan confused.

An elegant debut novel about two couples thrown together in 1960s New York City when the men are hired as co-pastors of a floundering Presbyterian church. Nearly the first half is devoted to the four main characters’ backstories and how each couple met. It’s a slow, subtle, quiet story (so much so that I only read the first half and skimmed the second), and I kept getting Charles and James, and Lily and Nan confused.

So here’s the shorthand: Charles is the son of an atheist Harvard professor and plans to study history until a lecture gets him thinking seriously about faith. Lily has closed herself off to life since she lost her parents in a car accident; though she eventually accedes to Charles’s romantic advances, she warns him she won’t bend where it comes to religion. James grew up in a poor Chicago household with an alcoholic father, while Nan is a Southern preacher’s daughter who goes up to Illinois to study music at Wheaton.

James doesn’t have a calling per se, but is passionate about social justice. As co-pastor, his focus will be on outreach and community service, while Charles’s will be on traditional teaching and ministry duties. Nan is desperate for a baby but keeps having miscarriages; Lily has twins, one of whom is autistic (early days for that diagnosis; doctors thought the baby should be institutionalized). Although Lily remains prickly, Nan and James’s friendship is a lifeline for them. The “dearly beloved” term thus applies outside of marriage as well, encompassing all the ties that sustain us – in the last line, Lily thinks, “these friends would forever be her stitches, her scaffold, her ballast, her home.”

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack.

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack. I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university.

I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university. Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year.

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year.