May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

10 Days in the USA and What I Read (Plus a Book Haul)

On October 29th, I went to an evening drinks party at a neighbour’s house around the corner. A friend asked me about whether the UK or the USA is “home” and I replied that the States feels less and less like home every time I go, that the culture and politics are ever more foreign to me and the UK’s more progressive society is where I belong. I even made an offhand comment to the effect of: once my mother passed, I didn’t think I’d fly back there often, if at all. I was thinking about 5–10 years into the future; instead, a few hours after I got home from the party, we were awoken by the middle-of-the-night phone call saying my mother had suffered a nonrecoverable brain bleed. The next day she was gone.

I haven’t reflected a lot on the irony of that timing, probably because it feels like too much, but it turns out I was completely wrong: in fact, I’m now returning to the States more often. With our mom gone and our dad not really in our lives, my sister and I have gotten closer. Since October I’ve flown back twice and she’s visited here once. There are 7.5 years between us and we’ve always been at different stages of life, with separate preoccupations and priorities; I was also lazy and let my mom be the go-between, passing family news back and forth. Now there’s a sense that we are all we have, and we have to stick together.

So it was doubly important for me to be there for my sister’s graduation from nursing school last week. If we follow each other on Facebook or Instagram, you will have already seen that she finished at the top of her cohort and was one of just two students recognized for academic excellence out of the college’s over 200 graduates – and all of this while raising four children and coping with the disruption of Mom’s death seven months ago. There were many times when she thought she would have to pause or give up her studies, but she persisted and will start work as a hospice nurse soon. We’re all as proud as could be, on our mom’s behalf, too.

The trip was a mixture of celebratory moments and sad duties. We started the process of going through our mom’s belongings and culling what we can, but the files, photos and mementoes are the real challenge and had to wait for another time. There were dozens of books I’d given her for birthdays and holidays, mostly by her favourite gentle writers – Gerald Durrell, Jan Karon, Gervase Phinn – invariably annotated with her name, the date and occasion. I looked back through them and then let them go.

Between my two suitcases I managed to bring back the rest of her first box of journals (there are 150 of them in total, spanning 1989 to 2022), and I’m halfway through #4 at the moment. We moved out of my first home when I was nine, and I don’t have a lot of vivid memories of those early years. But as I read her record of everyday life it’s like I’m right back in those rooms. I get new glimpses of myself, my dad, my sister, but especially of her – not as my mother, but as a whole person. As a child I never realized she was depressed: distressed about her job situation, worried over conflicts with her siblings and my sister, coping with ill health (she was later diagnosed with fibromyalgia) and resisting ageing. For as strong as her Christian faith was, she was really struggling in ways I couldn’t appreciate then.

I hope that later journals will introduce hindsight, now that she’s not around to give a more circumspect view. In any case, they’re an incredible legacy, a chance for me to relive much of my life that I otherwise would only remember in fragments through photographs, and perhaps have a preview of what I can expect from the course of our shared kidney disease.

What I Read

The Housekeepers by Alex Hay – A historical heist novel with shades of Downton Abbey, this comes out in July. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.

The Housekeepers by Alex Hay – A historical heist novel with shades of Downton Abbey, this comes out in July. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.

Cowboys Are My Weakness by Pam Houston – Terrific: stark, sexy stories about women who live out West and love cowboys and hunters (as well as dogs and horses). Ten of the stories are in the first person, voiced by women in their twenties and thirties who are looking for romance and adventure and anxiously pondering motherhood (“by the time you get to be thirty, freedom has circled back on itself to mean something totally different from what it did at twenty-one”). The remaining two are in the second person, which I always enjoy. The occasional Montana setting reminded me of stories I’ve read by Maile Meloy and Maggie Shipstead, while the relationship studies made me think of Amy Bloom’s work.

The Harpy by Megan Hunter – Read for Literary Wives club. Review coming up on Monday.

The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller – A solid set of narratives alternating between the POVs of four characters whose lives converge around a play inspired by the playwright’s loss of her boyfriend on one of the hijacked planes on 9/11. Her mixed feelings about him towards the end of his life and about being shackled to his legacy as his ‘widow’ reverberate in other sections: one about the lead actor, whose wife has ALS; and one about a widower the playwright is being set up with on a date. Fitting for a book about a play, the scenes feel very visual. A little underpowered, but subtlety is to be expected from a Miller novel. She, Anne Tyler and Elizabeth Berg write easy reads with substance, just the kind of book I want to take on an airplane, as indeed I did with this one. I read the first 2/3 on my travel day (although with the 9/11 theme this maybe wasn’t the best choice!).

For apposite plane reading, I also started Fly Girl by Ann Hood, her memoir of being a TWA flight attendant in the 1970s, the waning glory days of air travel. I’ve read 10 or so of Hood’s books before from various genres, but lost interest in the minutiae of her job applications and interviews. Another writer would probably have made a bigger deal of the inherent sexism of the profession, too. I read 30%.

For apposite plane reading, I also started Fly Girl by Ann Hood, her memoir of being a TWA flight attendant in the 1970s, the waning glory days of air travel. I’ve read 10 or so of Hood’s books before from various genres, but lost interest in the minutiae of her job applications and interviews. Another writer would probably have made a bigger deal of the inherent sexism of the profession, too. I read 30%.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano – I knew I wanted to read this even before it was Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters: Julia, Sylvie, and twins Cecilia and Emeline. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s and they marry and have a daughter; Sylvie, a budding librarian, makes out with boys in the stacks until her great romance comes along; Cecilia is an artist and Emeline loves babies and manages a nursery. More than once a character think of their collective story as a “soap opera,” and there’s plenty of melodrama here – an out-of-wedlock pregnancy, estrangements, a suicide attempt, a coming out, stealing another’s man – as well as far-fetched coincidences, including the two major deaths falling on the same day as a birth and a reconciliation.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano – I knew I wanted to read this even before it was Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters: Julia, Sylvie, and twins Cecilia and Emeline. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s and they marry and have a daughter; Sylvie, a budding librarian, makes out with boys in the stacks until her great romance comes along; Cecilia is an artist and Emeline loves babies and manages a nursery. More than once a character think of their collective story as a “soap opera,” and there’s plenty of melodrama here – an out-of-wedlock pregnancy, estrangements, a suicide attempt, a coming out, stealing another’s man – as well as far-fetched coincidences, including the two major deaths falling on the same day as a birth and a reconciliation.

There is such warmth and intensity to the telling, and brave reckoning with mental illness, prejudice and trauma, that I excused flaws such as dwelling overly much in characters’ heads through close third person narration, to the detriment of scenes and dialogue. I love sister stories in general, and the subtle echoes of Leaves of Grass and Little Women (the connections aren’t one to one and you’re kept guessing for most of the book who will be the Beth) add heft. I especially appreciated how a late parent is still remembered in daily life after 30 years have passed. This is, believe it or not, the second basketball novel I’ve loved this year, after Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe.

I always try to choose thematically appropriate reads, so I also started:

Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon – A memoir she began after her nonagenarian mother’s death with dementia. Intriguingly, the structure is not chronological but topic by topic, built around key relationships: so far I’ve read “My Mother and Her Bosses” and “My Mother: Words and Music.”

Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon – A memoir she began after her nonagenarian mother’s death with dementia. Intriguingly, the structure is not chronological but topic by topic, built around key relationships: so far I’ve read “My Mother and Her Bosses” and “My Mother: Words and Music.”

Grave by Allison C. Meier – My sister and I made a day trip up to my mother’s grave for the first time since her burial. She has a beautiful spot in a rural cemetery dating back to the 1780s, but it’s in full sun and very dry, so we tried to cheer up the dusty plot with some extra topsoil and grass seed, marigolds, and a butterfly flag.

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. In the third of the e-book I’ve read so far, she looks at American burial customs, the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial sites, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve been reading death-themed books for over a decade and have delighted in exploring cemeteries (including Mount Auburn, as part of my New England honeymoon) for even longer, so this is right up my street and one of the better Object Lessons monographs.

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. In the third of the e-book I’ve read so far, she looks at American burial customs, the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial sites, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve been reading death-themed books for over a decade and have delighted in exploring cemeteries (including Mount Auburn, as part of my New England honeymoon) for even longer, so this is right up my street and one of the better Object Lessons monographs.

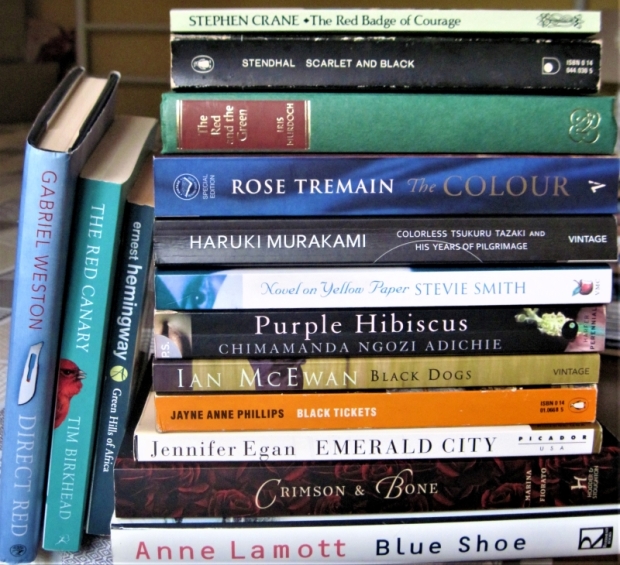

What I Bought

I traded in most of my mother’s books at 2nd & Charles and Wonder Book and Video but, no surprise, promptly spent the store credit on more secondhand books. Thanks to clearance shelves at both stores, I only had to chip in another $12.25 for the below haul, which also covered two Dollar Tree purchases (I felt bad for Susan Minot having signed editions end up remaindered!). Some tried and true authors here, as well as novelties to test out, with a bunch of short stories and novellas to read later in the year.

20 Books of Summer, #5–8: Anderson, Cusk, Fitch & L’Engle

I’ve been reading a feminist memoir set on Cape Cod, a subtle novel about the inner life and outward experiences of a writer, a soapy literary thriller about a troubled mother and teen daughter, and a slightly melancholy reminiscence of an aged mother succumbing to dementia.

A Walk on the Beach: Tales of Wisdom from an Unconventional Woman by Joan Anderson (2004)

This is the third volume in a loose autobiographical trilogy about Anderson’s experiment with taking a break from her marriage and living alone in a Cape Cod cottage to figure out what she really wanted from the rest of her life. Specifically, this book is about the inspirational relationship she formed with Joan Erikson, who moved to the area in her eighties when her husband, the famous psychologist Erik Erikson, was admitted to a care home. Joanie was a thinker and author in her own right, publishing books on life’s stages, especially those of older age. She encouraged Anderson to have the confidence to write her own story, and to take up challenges like a trip to Peru and learning to weave on a loom. Joanie’s aphoristic advice is valuable, but there’s a fair bit of overlap between this book and A Year by the Sea, which I would recommend over this.

This is the third volume in a loose autobiographical trilogy about Anderson’s experiment with taking a break from her marriage and living alone in a Cape Cod cottage to figure out what she really wanted from the rest of her life. Specifically, this book is about the inspirational relationship she formed with Joan Erikson, who moved to the area in her eighties when her husband, the famous psychologist Erik Erikson, was admitted to a care home. Joanie was a thinker and author in her own right, publishing books on life’s stages, especially those of older age. She encouraged Anderson to have the confidence to write her own story, and to take up challenges like a trip to Peru and learning to weave on a loom. Joanie’s aphoristic advice is valuable, but there’s a fair bit of overlap between this book and A Year by the Sea, which I would recommend over this.

My rating:

Some of Joan Erikson’s words of wisdom:

“Doing something with your hands, rather than your head, is often the best route to clarity.”

“wisdom comes from life’s experiences well digested. Stop relying so much on your mind and get in touch with experience.”

“The struggle is to try and obtain a sense of participation in your life the whole way through. We must treasure old age, but not wallow in nostalgia.”

Transit by Rachel Cusk (2016)

I finally made it through a Rachel Cusk book! (This was my third attempt; I made it just a few pages into Aftermath and 60 pages through Outline.) I suspected this would make a good plane read, and thankfully I was right. Each chapter is a perfectly formed short story, a snapshot of one aspect of Faye’s life and the relationships that have shaped her: a former lover she bumps into in London, a builder who tells her the flat she’s bought is a lost cause, the awful downstairs neighbors who hate her with a passion, the fellow writers (based on Edmund White and Karl Ove Knausgaard?) at a literary festival event who hog most of the time, the jolly Eastern European construction workers who undertake her renovations, a childless friend who works in fashion design, and a country cousin who’s struggling with his new blended family.

I finally made it through a Rachel Cusk book! (This was my third attempt; I made it just a few pages into Aftermath and 60 pages through Outline.) I suspected this would make a good plane read, and thankfully I was right. Each chapter is a perfectly formed short story, a snapshot of one aspect of Faye’s life and the relationships that have shaped her: a former lover she bumps into in London, a builder who tells her the flat she’s bought is a lost cause, the awful downstairs neighbors who hate her with a passion, the fellow writers (based on Edmund White and Karl Ove Knausgaard?) at a literary festival event who hog most of the time, the jolly Eastern European construction workers who undertake her renovations, a childless friend who works in fashion design, and a country cousin who’s struggling with his new blended family.

Like in Outline, the novel is based largely on the conversations Faye overhears or participates in (“I had found out more, I said, by listening than I had ever thought possible”), but I sensed more of her personality this time, and could relate to her questioning: Why do her neighbors hate her so? How much of her life is fated, and how much has she chosen? I doubt I’ll read another book by Cusk, but I ended up surprisingly grateful to have gotten hold of this one as a free proof copy of the new paperback edition from the Faber Spring Party.

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

“we examine least what has formed us the most, and instead find ourselves driven blindly to re-enact it.”

“Without children or partner, without meaningful family or a home, a day can last an eternity: a life without those things is a life without a story, a life in which there is nothing – no narrative flights, no plot developments, no immersive human dramas – to alleviate the cruelly meticulous passing of time.”

White Oleander by Janet Fitch (1999)

Man, that Oprah knows how to pick ’em! This was a terrific read; I’m not sure why I’d never gotten to it before. I read huge chunks during my travel to the States and then slowed down quite a bit, which was a shame because it meant I felt less connected to Astrid’s later struggles in the foster care system. It’s an atmospheric novel full of oppressive Los Angeles heat and a classic noir flavor that shades into gritty realism as it goes on, taking us from when Astrid is 12 to when she’s a young woman out in the world on her own.

Man, that Oprah knows how to pick ’em! This was a terrific read; I’m not sure why I’d never gotten to it before. I read huge chunks during my travel to the States and then slowed down quite a bit, which was a shame because it meant I felt less connected to Astrid’s later struggles in the foster care system. It’s an atmospheric novel full of oppressive Los Angeles heat and a classic noir flavor that shades into gritty realism as it goes on, taking us from when Astrid is 12 to when she’s a young woman out in the world on her own.

Astrid’s mother Ingrid, an elitist poet, becomes obsessed with a lover who spurned her and goes to jail for his murder. Bouncing between foster homes and children’s institutions, Astrid is plunged into a world of sex, drugs, violence and short-lived piety. “Like a limpet I attached to anything, anyone who showed me the least attention,” she writes. Her role models change over the years, but always in the background is the icy influence of her mother, through letters and visits.

Fitch’s writing is sumptuous, as in a house “the color of a tropical lagoon on a postcard thirty years out of date, a Gauguin syphilitic nightmare.” I might have liked a tiny bit more of Ingrid in the book, but I can still recommend this one wholeheartedly as summer reading.

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

The knock-out opening two lines: “The Santa Anas blew in hot from the desert, shriveling the last of the spring grass into whiskers of pale straw. Only the oleanders thrived, their delicate poisonous blossoms, their dagger green leaves.”

“I couldn’t imagine my mother in prison. She didn’t smoke or chew on toothpicks. She didn’t say ‘bitch’ or ‘fuck.’ She spoke four languages, quoted T. S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas, drank Lapsang souchong out of a porcelain cup. She had never been inside a McDonald’s. She had lived in Paris and Amsterdam. Freiburg and Martinique. How could she be in prison?”

The Summer of the Great-Grandmother by Madeleine L’Engle (1974)

L’Engle is better known for children’s books, but wrote tons for adults, too. In this second volume of The Crosswicks Journal, she recounts her family history as a way of remembering on behalf of her mother, who at age 90 was slipping into dementia in her final summer. “I talked awhile, earlier this summer, about wanting my mother to have a dignified death. But there is nothing dignified about incontinence and senility.” L’Engle found herself in the unwanted position of being like her mother’s mother, and had to accept that she had no control over the situation. “This summer is practice in dying for me as well as for my mother.”

L’Engle is better known for children’s books, but wrote tons for adults, too. In this second volume of The Crosswicks Journal, she recounts her family history as a way of remembering on behalf of her mother, who at age 90 was slipping into dementia in her final summer. “I talked awhile, earlier this summer, about wanting my mother to have a dignified death. But there is nothing dignified about incontinence and senility.” L’Engle found herself in the unwanted position of being like her mother’s mother, and had to accept that she had no control over the situation. “This summer is practice in dying for me as well as for my mother.”

One of the reasons L’Engle was driven to write science fiction was because she couldn’t reconcile the idea of permanent human extinction with her Christian faith, but nor could she honestly affirm every word of the Creed. Hers is a more broad-minded, mystical spirituality that really appeals to me. (Her early life reminds me of May Sarton’s, as recounted in I Knew a Phoenix: both were born right around World War I, raised partially in Europe and sent to boarding school; a frequent theme in their nonfiction is the regenerative power of solitude and of the writing process itself.)

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

“I said [in a lecture] that the artist’s response to the irrationality of the world is to paint or sing or write, not to impose restrictive rules but to rejoice in pattern and meaning, for there is something in all artists which rejects coincidence and accident. And I went on to say that we must meet the precariousness of the universe without self-pity, and with dignity and courage.”

“Our lives are given a certain dignity by their very evanescence. If there were never to be an end to my quiet moments at the brook, if I could sit on the rock forever, I would not treasure these minutes so much. If our associations with the people we love were to have no termination, we would not value them as much as we do.”

20 Books of Summer 2018

This is my first year joining in with the 20 Books of Summer challenge run by Cathy of 746 Books. I’ve decided to put two twists on it. One: I’ve only included books that I own in print, to work on tackling my mountain of unread books (300+ in the house at last count). As I was pulling out the books that I was most excited to read soon, I noticed that most of them happened to be by women. So for my second twist, all 20 books are by women. Why not? I’ve picked roughly half fiction and half life writing, so over the next 12 weeks I just need to pick one or two from the below list per week, perhaps alternating fiction and non-. I’m going to focus more on the reading than the reviewing, but I might do a few mini roundup posts.

I’m doing abysmally with the goal I set myself at the start of the year to read lots of travel classics and biographies, so I’ve chosen one of each for this summer, but in general my criteria were simply that I was keen to read a book soon, and that it mustn’t feel like hard work. (So, alas, that ruled out novels by Elizabeth Bowen, Ursula K. LeGuin and Virginia Woolf.) I don’t insist on “beach reads” – the last two books I read on a beach were When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi and Grief Cottage by Gail Godwin, after all – but I do hope that all the books I’ve chosen will be compelling and satisfying reads.

- To Throw Away Unopened by Viv Albertine – I picked up a copy from the Faber Spring Party, having no idea who Albertine was (guitarist of the all-female punk band The Slits). Everyone I know who has read this memoir has raved about it.

- Lit by Mary Karr – I’ve read Karr’s book about memoir, but not any of her three acclaimed memoirs. This, her second, is about alcoholism and motherhood.

- Korma, Kheer and Kismet: Five Seasons in Old Delhi by Pamela Timms – I bought a bargain copy at the Wigtown Festival shop earlier in the year. Timms is a Scottish journalist who now lives in India. This should be a fun combination of foodie memoir and travel book.

- Direct Red: A Surgeon’s Story by Gabriel Weston (a woman, honest!) – Indulging my love of medical memoirs here. I bought a copy at Oxfam Books earlier this year.

5. May Sarton by Margot Peters – I’ve been on a big May Sarton kick in recent years, so have been eager to read this 1997 biography, which apparently is not particularly favorable.

5. May Sarton by Margot Peters – I’ve been on a big May Sarton kick in recent years, so have been eager to read this 1997 biography, which apparently is not particularly favorable.

6. Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle by Dervla Murphy – I bought this 1960s hardback from a charity shop in Cambridge a couple of years ago. It will at least be a start on that travel classics challenge.

7. Girls on the Verge: Debutante Dips, Drive-bys, and Other Initiations by Vendela Vida – This was Vida’s first book. It’s about coming-of-age rituals for young women in America.

8. Four Wings and a Prayer: Caught in the Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly by Sue Halpern – Should fall somewhere between science and nature writing, with a travel element.

9. The Summer of the Great-Grandmother by Madeleine L’Engle – L’Engle is better known for children’s books, but she wrote tons for adults, too: fiction, memoirs and theology. I read the stellar first volume of the Crosswicks Journal, A Circle of Quiet, in September 2015 and have meant to continue the series ever since.

10. Sunstroke by Tessa Hadley – You know how I love reading with the seasons when I can. This slim 2007 volume of stories is sure to be a winner. Seven of the 10 originally appeared in the New Yorker or Granta.

11. Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore – I’ve only ever read Dunmore’s poetry. It’s long past time to try her fiction. This one comes highly recommended by Susan of A life in books.

12. We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates – Oates is intimidatingly prolific, but I’m finally going to jump in and give her a try.

13. Amrita by Banana Yoshimoto – A token lit in translation selection. “This is the story of [a] remarkable expedition through grief, dreams, and shadows to a place of transformation.” (Is it unimaginative to say that sounds like Murakami?)

14. Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – How have I not read any of her fiction yet?! This has been sitting on my shelf for years. I only vaguely remember the story line from the film, so it should be fairly fresh for me.

15. White Oleander by Janet Fitch – An Oprah’s Book Club selection from 1999. I reckon this would make a good beach or road trip read.

16. Drowning Ruth by Christina Schwarz – Another Oprah’s Book Club favorite from 2000. Set in Wisconsin in the years after World War I.

- Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler – Tyler novels are a tonic. I have six unread on the shelf; the blurb on this one appealed to me the most. This summer actually brings two Tylers as Clock Dance comes out on July 12th – I’ll either substitute that one in, or read both!

18. An Untamed State by Roxane Gay – I’ve only read Gay’s memoir, Hunger. She’s an important cultural figure; it feels essential to read all her books. I expect this to be rough.

19. Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay – This has been on my radar for such a long time. After loving my first Hay novel (A Student of Weather) last year, what am I waiting for?

20. Fludd by Hilary Mantel – I haven’t read any Mantel in years, not since Bring Up the Bodies first came out. While we all await the third Cromwell book, I reckon this short novel about a curate arriving in a fictional town in the 1950s should hit the spot.

I’ll still be keeping up with my review books (paid and unpaid), blog tours, advance reads and library books over the summer. The aim of this challenge, though, is to make inroads into the physical TBR. Hopefully the habit will stick and I’ll keep on plucking reads from my shelves during the rest of the year.

Where shall I start? If I was going to sensibly move from darkest to lightest, I’d probably start with An Untamed State and/or Lit. Or I might try to lure in the summer weather by reading the two summery ones…

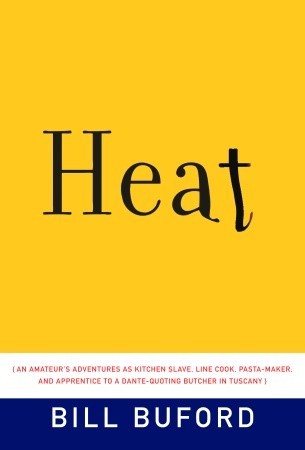

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and

Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and

The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact.

The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact. This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal.

This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal. I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the

I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the  There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.

There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.

What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. As Adah concludes, “We are the balance of our damage and our transgressions.”

What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. As Adah concludes, “We are the balance of our damage and our transgressions.”

(This was a Twitter buddy read with Naomi of

(This was a Twitter buddy read with Naomi of

The title feels like an echo of An American Tragedy. It’s both monolithic and generic, as if saying: Here’s a marriage; make of it what you will. Is it representative of the average American situation, or is it exceptional? Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. Through their alternating first-person narration and their letters back and forth while Roy is incarcerated, we learn more about this couple: how their family circumstances shaped them, how they met, and how they drift apart as Celestial turns to her childhood friend, Andre, for companionship. When Roy is granted early release, he returns to Georgia to find Celestial and see what might remain of their marriage. I ached for all three main characters: It’s an impossible situation. The novel ends probably the only way it could, on a realistic yet gently optimistic note. Life goes on, if not how you expect, and there will be joys still to come.

The title feels like an echo of An American Tragedy. It’s both monolithic and generic, as if saying: Here’s a marriage; make of it what you will. Is it representative of the average American situation, or is it exceptional? Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. Through their alternating first-person narration and their letters back and forth while Roy is incarcerated, we learn more about this couple: how their family circumstances shaped them, how they met, and how they drift apart as Celestial turns to her childhood friend, Andre, for companionship. When Roy is granted early release, he returns to Georgia to find Celestial and see what might remain of their marriage. I ached for all three main characters: It’s an impossible situation. The novel ends probably the only way it could, on a realistic yet gently optimistic note. Life goes on, if not how you expect, and there will be joys still to come. (Another Twitter buddy read, with Laila of

(Another Twitter buddy read, with Laila of

I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an

I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an  I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them.

I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them. Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.)

Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.) Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away.

Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away. This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge.

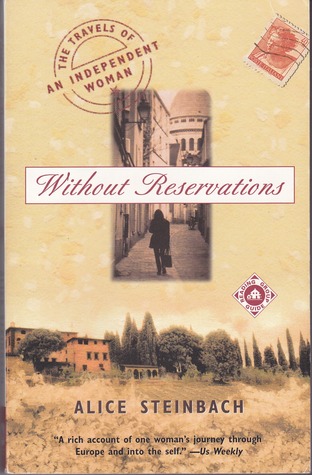

This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge. In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone.

In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone.