Final Reading Statistics for 2025 & Goals for 2026

Happy New Year! We went to a neighbours’ party again this year and played silly games and chased their kittens until 1:30 a.m. It was a fun, low-key way to see in 2026.

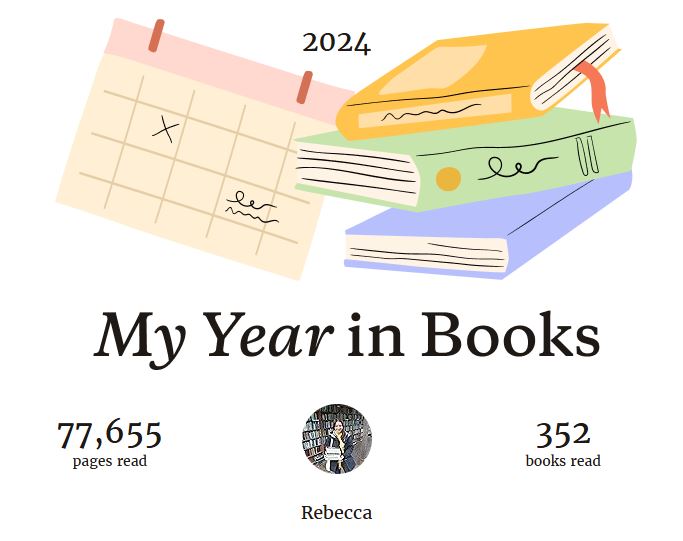

I read 313 books last year. (2024’s total of 352 will never be topped!) Initially, I set a goal of 350, but by midyear I downgraded it to 300 and it was easy to reach. I can’t pinpoint a particular reason for the decline. In general, I felt like I was chasing my tail all year, despite having less work on than ever (but increased volunteering commitments). Often, I struggled with fatigue or being on the verge of illness. What a fun guessing game: is it long Covid or perimenopause?

Goodreads was glitchy for me all year, randomly counting books two or three times and falsely inflating my total by a whole extra 33 books at one point. It also has a lot of annoying, automatically generated book records that duplicate ISBNs or add the publisher to the title field. So I’m thinking about moving over to StoryGraph this year – I just imported my Goodreads library – though I always quail at learning new online systems. It would also be the next logical step in divesting from Am*zon.

The year that was…

2025’s notable happenings:

- Twice assessing the ‘proper’ (published) books as a McKitterick Prize judge

- Adopting crazy Benny (though that was after losing our precious Alfie)

- Acquiring a secondhand electric car for the household

- Holidays in Hay-on-Wye; the Outer Hebrides; Suffolk; Berlin and Lübeck, Germany

- A summer visit from my sister and brother-in-law

- Having the windows and door replaced in the back of our house; and the hall and stairwell/landing redecorated

- I got ever more into gin and cocktails, with tastings in Abingdon and Wantage (and in December I led two informal tastings for friends). I also acquired the taste for rum!

The reading statistics, as compared to 2024:

Fiction: 54.7% (↑3.3%)

Nonfiction: 31.6% (↓0.2%)

Poetry: 13.7% (↓3.1%)

Female author: 67.7% (↓0.2%)

Lydi Conklin was one of 10 nonbinary authors I read from this year. Had I read their novel earlier, this would have made it into my Cover Love post!

Nonbinary author: 3.2% (↑2.1%)

BIPOC author: 18.5% (↑0.1%)

How to get it to 25% or more??

LGBTQ: 20.4% (↓1.1%)

(Author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) It’s the first time this has decreased since 2021, but I’m still pleased with the figure overall.

Work in translation: 9.6% (↑3.6%)

Going the right way with this trend! 10% seems like a good minimum to aim for. I find I have to make a conscious effort by accepting translated review copies or picking them off my shelves to tie in with particular reading challenges.

German (6) – mainly because of our trip in September

French (5)

Swedish (4)

Korean (3)

Italian (2)

Italian (2)

Japanese (2)

Spanish (2)

Chinese (1)

Dutch (1)

Norwegian (1)

Polish (1)

Portuguese (1)

Russian (1)

2025 (or pre-release 2026) books: 55.6% (↑3.2%)

Backlist: 44.4%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read eight pre-1950 books, the oldest being Diary of a Nobody from 1892.

E-books: 35.5% (↑3.4%)

Print books: 64.5%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews. The number of overall Shelf Awareness reviews will be decreasing because of changes to their publishing model, so this figure may well change by next year.

Rereads: 11, vs. last year’s 18

I managed nearly one a month. Like last year, three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences of the year, so I should really reread more often.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

- 69,616 pages read

- Average book length: 221 pages (just one off of last year’s 220; in previous years it has always been 217–225, driven downward by poetry collections and novellas)

- Average rating for 2025: 6 (identical to the last three years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2024:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 33.9% (↓10.9%)

- Public library: 18.8% (↑0.4%)

- Free (gifts, giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 15.3% (↑2.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss or BookSirens: 15% (↑7.2%)

- Secondhand purchase: 12.8% (↑1.3%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.6% (↓0.5%)

- University library: 1.3% (↓0.7%)

- Other (church theological library): 0.3% (↑0.3%)

I’m pleased that 30.3% of my reading was from my own shelves, versus last year’s 24%. It looks like I mainly achieved this through a reduction in review copies. In 2026, I’d like to read even more backlist material from my own shelves (including rereads). This will be a particular focus in January, and then I’ll plan how to incorporate it for the rest of the year.

I have an absurd number of review books to catch up on (42), some stretching back to 2022 – the year of my mother’s death, which put me off my stride in many ways – as well as part-read books (116) to get real about and either finish or call DNFs and clear from my shelves. Dealing with these can be part of the reading-from-my-shelves initiative.

What trends did you see in your year’s reading? What is your plan for 2026?

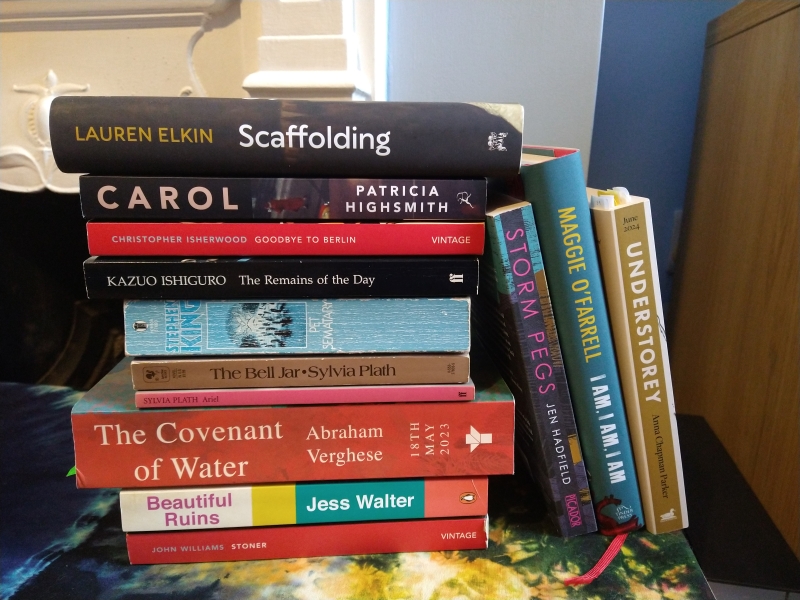

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

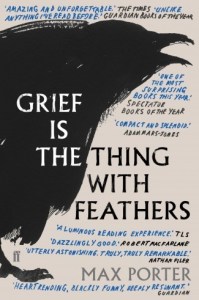

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

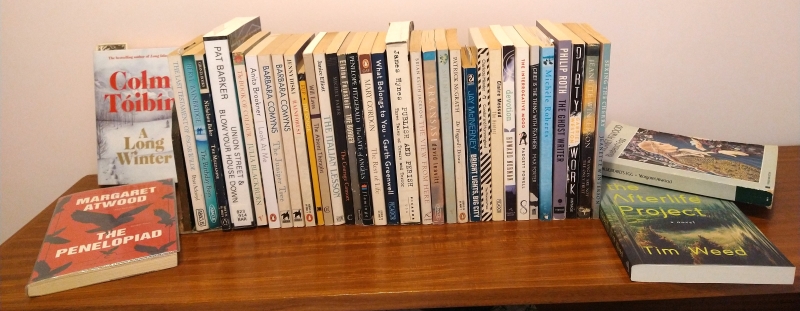

#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

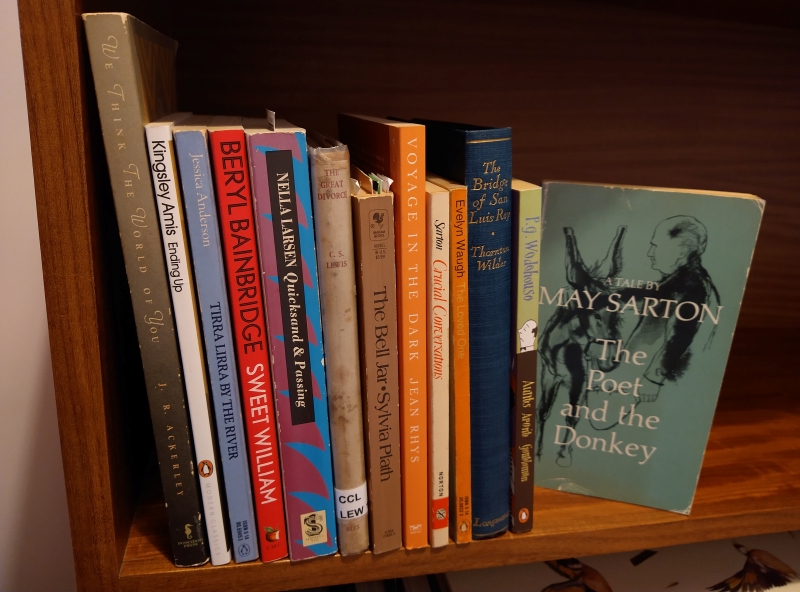

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

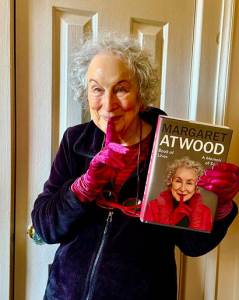

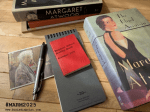

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

Short Nonfiction

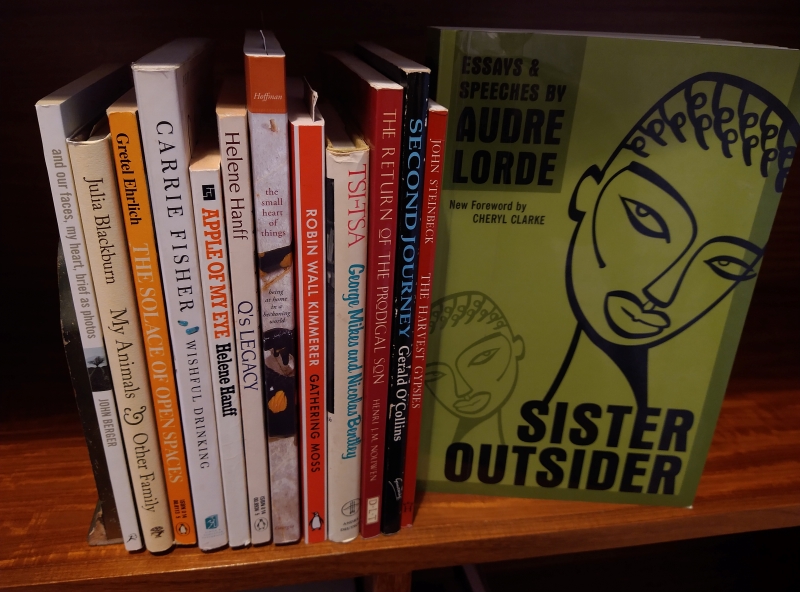

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

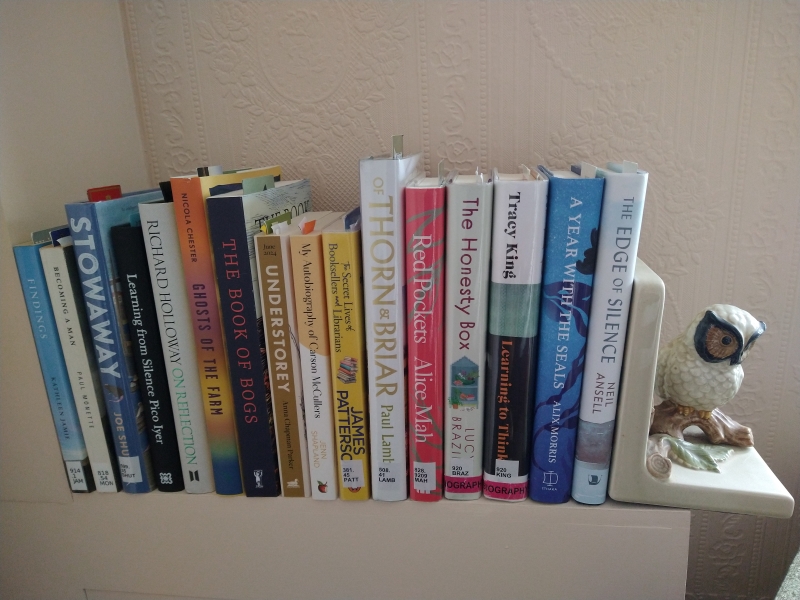

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

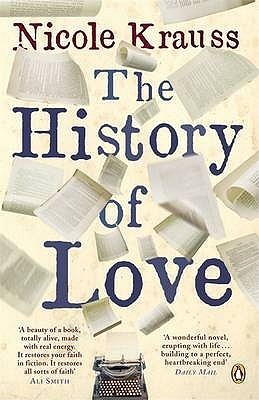

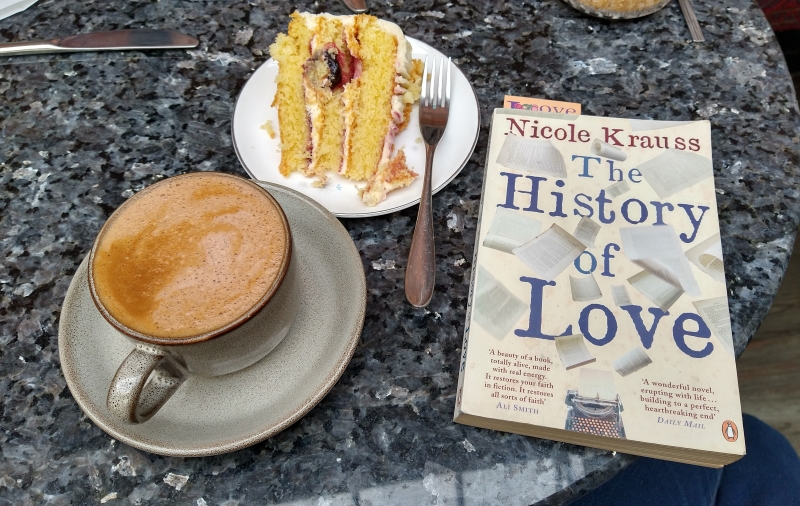

Adventures in Rereading: The History of Love by Nicole Krauss for Valentine’s Day

Special Valentine’s edition. Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet manage a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the ninth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024!

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library)

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Finishing my reread during a coffee date in Hungerford this morning.

My original rating (2011): ![]()

When I first read this, I mostly considered it in comparison to Krauss’s former husband Jonathan Safran Foer’s work. (I’ve long since read everything by both of them.) I noted then that it

has a lot of elements in common with Everything is Illuminated, such as a preoccupation with Eastern European and Jewish ancestry, quirky methods of narration including multiple voices, and a sweet humour that lies alongside such heart-rending stories of family and loss that tears are never far from your eyes. Leo Gursky and Alma Singer are delightful and distinct characters. I wasn’t sure about the missing/plagiarized/mistaken The History of Love itself; the ruined copies, the different translations, the way the manuscript was constantly changing hands – all this was intriguing, but the book itself was a postmodern jumble of magic realism and pointless meanderings of thought.

Dang, I was harsh! But admirably pithy about the plot. It’s intriguing that I’ve successfully reread Krauss but failed with Foer when I attempted Everything is Illuminated again in 2020. Reading the first, 9/11-set section of Confessions by Catherine Airey, I’ve also been recalling his Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and thinking it probably wouldn’t stand up to a reread either. I suspect I’d find it mawkish, especially with its child narrator. Alma evades that trap, perhaps by being that little bit older, though she sounds young because of how geeky and sheltered she is.

Final Reading Statistics for 2024

Happy New Year! Even though we were out at neighbours’ until 2:45 a.m. (who are these party animals?!), I’m feeling bright-eyed and bushy-tailed today and looking forward to a special brunch at our favourite Newbury establishment. Despite all evidence to the contrary in the news – politically, environmentally, internationally – I’m choosing to be optimistic about what 2025 will hold. What hope I have comes from community and grassroots efforts.

In other good news, 2024 saw my highest reading total yet! (My usual average, as in 2019–21 and 2023, is 340.) Last year I challenged myself to read 350 books and I managed it easily, even though at one point in the middle of the year I was far behind and it didn’t look possible.

Reading a novella a day in November was certainly a major factor in meeting my goal. I also tend to prioritize poetry collections and novellas for my Shelf Awareness reviewing, and in general I consider it a bonus if a book is closer to 200 pages than 300+.

The statistics

Fiction: 51.4%

Nonfiction: 31.8% (similar to last year’s 31.2%)

Poetry: 16.8% (identical to last year!)

Female author: 67.9% (close to last year’s 69.7%)

Male author: 29.6%

Nonbinary author: 1.1%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 1.4%

BIPOC author: 18.4%

This has dropped a bit compared to previous years’ 22.4% (2023), 20.7% (2022), and 18.5% (2021). My aim will be to make it 25% or more.

LGBTQ: 21.6%

(Based on the author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) This has been increasing from 11.8% (2021), 8.8% (2022), and 18.2% (2023). I’m pleased!

Work in translation: 6%

I read only 21 books in translation last year, alas. This is an unfortunate drop from the previous year’s 10.6%. I do prefer to be closer to 10%, so I will need to make a conscious effort to borrow translated books and incorporate them in my challenges.

French (7)

German (4)

Norwegian (3)

Spanish (3)

Italian (1)

Latvian (1) – a new language for me to have read from

Swedish (1)

+ Misc. in a story anthology

2024 (or pre-release 2025) books: 52.3% (up from 44.7% last year)

Backlist: 47.7%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read five pre-1950 books, the oldest being Howards End and Kilmeny of the Orchard, both from 1910. I should definitely pick up something from the 19th century or earlier next year!

E-books: 32.1% (up from 27.4% last year)

Print books: 67.9%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews.

Rereads: 18

I doubled last year’s 9! I’m really happy with this 1.5/month average. Three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences for the year.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

Average book length: 220 pages (in previous years it has been 217 and 225)

Average rating for 2024: 3.6 (identical to the last two years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2023:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 44.8% (↑1.3%)

- Public library: 18.4% (↓5.7%)

- Secondhand purchase: 11.5% (↑1.7%)

- Free (giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 9.8% (↑3.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss, BookSirens or Project Gutenberg: 8.8% (↑2%)

- Gifts: 2.6% (↓1.5%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.1% (↓2.6%)

- University library: 2% (↓1.2%)

So, like last year, nearly a quarter of my reading (24%) was from my own shelves. I’d like to make that more like a third to half, which would be better achieved by a reduction in the number of review copies rather than a drop in my library borrowing. It would also ensure that I read more backlist books.

What trends and changes did you see in your year’s reading?

Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

My Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Like many bloggers and other book addicts, I’m irresistibly drawn to the new books released each year. However, I consistently find that many memorable reads were published earlier. A few of these are from 2022 or 2023 and most of the rest are post-2000; the oldest is from 1910. These 14 selections (alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order), together with my Best of 2024 post coming up on Tuesday, make up about the top 10% of my year’s reading. Repeated themes included adolescence, parenting (especially motherhood) and trauma. The two not pictured below were read electronically.

Fiction

Fun facts:

- I read 4 of these for book club (Forster, Mandel, Munro and Obreht)

- 3 (Mandel, McEwan and Obreht) were rereads

- I read 2 as part of my Carol Shields Prize shadowing (Foote and Zhang)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Nonfiction

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research. The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint.

The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint. Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride.

Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride. As I found when I

As I found when I  I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

My hold on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, Book of Lives, arrived in late November. It’ll be my first read for Doorstoppers in December. I’d also been casually rereading her 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg and managed the first two stories; I’ll return to the rest next year. A recent