Summery Reading, Part I: Heatwave, Summer Fridays

Here we are between short, bearable heat waves. As the climate changes, I’m more grateful than ever to live somewhere with reasonably mild and predictable weather; I don’t miss the swampy humidity of the Maryland summers I grew up with one bit. Today I have some brief thoughts on a first pair of summer-themed reads I picked up last month: a queasy coming-of-age novella about French teenagers’ self-destructive actions on a camping holiday; and a fun, nostalgic romance novel set in New York City at the turn of the millennium.

Heatwave by Victor Jestin (2019; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Sam Taylor]

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

The rest of the book takes place over about 24 hours, the final day of a two-week vacation. Leo stumbles about as if in a trance, outwardly relating to his family, a male friend who seems to have a crush on him, and girls he’d like to sleep with, but all the while inwardly wondering what to do next. “I hadn’t made many stupid mistakes in my seventeen years of life. This one was difficult to understand. It all happened too fast; I felt powerless.” This is interesting enough if you like unreliable teenage narrators or are drawn by the critics’ comparisons to Françoise Sagan – accurate for the sense of sleepwalking toward disaster. One could easily breeze through the 104 pages during one hot afternoon. It didn’t stand out to me particularly, though. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell (2024)

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

It’s overlong and reasonably predictable, but I enjoyed the languid unfolding of the romance over the weeks of summer 1999. It was truly a simpler time when you had to dial up and wait for an inbox to load instead of having it in your pocket 24/7. Every Friday afternoon, Sawyer and Nick do touristy things like taste-test hotdogs and slushees, ride the Staten Island ferry back and forth all day, and visit little-known bars and restaurants Nick knows through his amateur rock band. They try to convince themselves that these are not dates. It’s like time outside of time for them, and a chance to sightsee in one’s own town. Eventually, though, Sawyer has to face reality. The 2001 framing story reflects the fact that, after the events of 9/11, many asked themselves what they really wanted out of life. This was cute but doesn’t quite live up to, e.g., Romantic Comedy. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Any “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

The Mystery of Henri Pick by David Foenkinos (Walter Presents Blog Tour)

A library populated entirely by rejected books? Such was Richard Brautigan’s brainchild in one of his novels, and after his suicide a fan made it a reality. Now based in Vancouver, Washington, the Brautigan Library houses what French novelist David Foenkinos calls “the world’s literary orphans.” In The Mystery of Henri Pick, he imagines what would have happened had a French librarian created its counterpart in a small town in Brittany and a canny editor discovered a gem of a bestseller among its dusty stacks.

Delphine Despero is a rising Parisian editor who’s fallen in love with her latest signed author, Frédéric Koskas. Unfortunately, his novel The Bathtub is a flop, but he persists in writing a second, The Bed. On a trip home to Brittany so Frédéric can meet her parents, he and Delphine drop into the library of rejected books at Crozon and find a few amusing turkeys – but also a masterpiece. The Last Hours of a Love Affair is what it says on the tin, but also incorporates the death of Pushkin. The name attached to it is that of the late pizzeria owner in Crozon. His elderly widow and middle-aged daughter had no idea that their humble Henri had ever had literary ambitions, let alone that he had a copy of Eugene Onegin in the attic.

Delphine Despero is a rising Parisian editor who’s fallen in love with her latest signed author, Frédéric Koskas. Unfortunately, his novel The Bathtub is a flop, but he persists in writing a second, The Bed. On a trip home to Brittany so Frédéric can meet her parents, he and Delphine drop into the library of rejected books at Crozon and find a few amusing turkeys – but also a masterpiece. The Last Hours of a Love Affair is what it says on the tin, but also incorporates the death of Pushkin. The name attached to it is that of the late pizzeria owner in Crozon. His elderly widow and middle-aged daughter had no idea that their humble Henri had ever had literary ambitions, let alone that he had a copy of Eugene Onegin in the attic.

The Last Hours of a Love Affair becomes a publishing sensation – for its backstory more than its writing quality – yet there are those who doubt that Henri Pick could have been its author. The doubting faction is led by Jean-Michel Rouche, a disgraced literary critic who, having lost his job and his girlfriend, now has all the free time in the world to research the foundation of the Library of Rejects and those who deposited manuscripts there. Just when you think matters are tied up, Foenkinos throws a curveball.

This was such a light and entertaining read that I raced through. It has the breezy, mildly zany style I associate with films like Amélie. Despite the title, there’s not that much of a mystery here, but that suited me since I pretty much never pick up a crime novel. Foenkinos inserts lots of little literary in-jokes (not least: this is published by Pushkin Press!), and through Delphine he voices just the jaded but hopeful attitude I have towards books, especially as I undertake my own project of assessing unpublished manuscripts:

She had about twenty books to read during August, and they were all stored on her e-reader. [Her friends] asked her what those novels were about, and Delphine confessed that, most of the time, she was incapable of summarizing them. She had not read anything memorable. Yet she continued to feel excited at the start of each new book. Because what if it was good? What if she was about to discover a new author? She found her job so stimulating, it was almost like being a child again, hunting for chocolate eggs in a garden at Easter.

Great fun – give it a go!

My rating:

(Originally published in 2016. Translation from the French by Sam Taylor, 2020.)

My thanks to Poppy at Pushkin Press for arranging my e-copy for review.

(Walter Presents, a foreign-language drama streaming service, launched in the UK (on Channel 4) in 2016 and is also available in the USA, Australia, and various European countries.)

I was delighted to be part of the Walter Presents blog tour. See below for details of where other books and reviews have featured.

A Hundred Million Years and a Day by Jean-Baptiste Andrea

Stanislas Armengol remembers finding his first trilobite at the age of six. His fossils and his dog were his best friends during a lonely childhood dominated by a violent father nicknamed “The Commander.” Now, in the summer of 1954, Stan is a 52-year-old paleontologist embarking on the greatest project of his career. He sold his apartment in Paris to finance this expedition to the French/Italian Alps in search of a “dragon” (perhaps a diplodocus) said to be buried in a glacier between three mountain peaks.

Stanislas Armengol remembers finding his first trilobite at the age of six. His fossils and his dog were his best friends during a lonely childhood dominated by a violent father nicknamed “The Commander.” Now, in the summer of 1954, Stan is a 52-year-old paleontologist embarking on the greatest project of his career. He sold his apartment in Paris to finance this expedition to the French/Italian Alps in search of a “dragon” (perhaps a diplodocus) said to be buried in a glacier between three mountain peaks.

“A scientist does not unquestioningly swallow a tall tale without demanding some proof, some concrete detail,” Stan insists. “Doubt is our religion.” But he’s seen a promising bone fragment from the region, and his excitement soon outweighs his uncertainty. This is his chance to finally make a name for himself. Arriving from Turin to join Stan are his friend and former assistant Umberto, and Umberto’s assistant, Peter. Gio, a local, will be their guide. It’s a tough climb requiring ropes and harnesses. As autumn approaches, and then winter, the hunt for the fossil becomes more frantic. The others are prepared to come back next year if it’s no longer sensible to continue, but Stan has staked everything on the venture and won’t quit.

Stan’s obsession puts him in touch with deep time – he’s “someone whose profession forces him to think in terms of millions of years” – but his thoughts keep returning to moments of joy or distress from his childhood. Although she died when he was nine years old, his beloved mother still looms large in his memory. Even as the realities of cold and hunger intensify, his past comes to seem more vivid than his present.

This French bestseller was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française last year. Sam Taylor’s translation is flawless, as always (I only noted one tiny phrase that felt wrong for the time period – “honestly, what a brat” – though for all I know it’s off in the original, too). However, I found the novella uncannily similar to Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini, which is about a hermit in the Italian Alps whose mental illness is exacerbated by snowy solitude. I found Morandini’s witty, macabre story more memorable. Although A Hundred Million Years and a Day is well constructed, there’s something austere about it that meant my admiration never quite moved into fondness.

My rating:

A Hundred Million Years and a Day will be published in the UK tomorrow, the 11th. My thanks to Gallic Books for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Recommended June Releases

I have an all-female line-up for you this time, with selections ranging from a YA romance in verse to a memoir by a spiritual recording artist. There’s a very random detail that connects two of these books – look out for it!

In Paris with You by Clémentine Beauvais

[Faber & Faber, 7th]

I don’t know the source material Beauvais was working with (Eugene Onegin, 1837), but still enjoyed this YA romance in verse. Eugene and Tatiana meet by chance in Paris in 2016 and the attraction between them is as strong as ever, but a possible relationship is threatened by memories of a tragic event from 10 years ago involving Lensky, Eugene’s friend and the boyfriend of Tatiana’s older sister Olga. I’m in awe at how translator Sam Taylor has taken the French of her Songe à la douceur and turned it into English poetry with the occasional rhyme. This is a sweet book that would appeal to John Green’s readers, but it’s more sexually explicit than a lot of American YA, so is probably only suitable for older teens. (Proof copy from Faber Spring Party)

I don’t know the source material Beauvais was working with (Eugene Onegin, 1837), but still enjoyed this YA romance in verse. Eugene and Tatiana meet by chance in Paris in 2016 and the attraction between them is as strong as ever, but a possible relationship is threatened by memories of a tragic event from 10 years ago involving Lensky, Eugene’s friend and the boyfriend of Tatiana’s older sister Olga. I’m in awe at how translator Sam Taylor has taken the French of her Songe à la douceur and turned it into English poetry with the occasional rhyme. This is a sweet book that would appeal to John Green’s readers, but it’s more sexually explicit than a lot of American YA, so is probably only suitable for older teens. (Proof copy from Faber Spring Party)

Favorite lines:

“Her heart takes the lift / up to her larynx, / where it gets stuck / hammering against the walls of her neck.”

“an adult with a miniature attention span, / like everyone else, refreshing, updating, / nibbling at time like a ham baguette.”

“helium balloons in the shape of spermatozoa straining towards the dark sky.”

My rating:

Implosion: A Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter by Elizabeth W. Garber

[She Writes Press, 12th]

The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s–70s. This and his other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Manic depression meant he had periods of great productivity but also weeks when he couldn’t get out of bed. He and Elizabeth connected over architecture, like when he helped her make a scale model of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye for a school project, but it was hard for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation or his wife’s desire to go back to school and have her own career.

The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s–70s. This and his other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Manic depression meant he had periods of great productivity but also weeks when he couldn’t get out of bed. He and Elizabeth connected over architecture, like when he helped her make a scale model of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye for a school project, but it was hard for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation or his wife’s desire to go back to school and have her own career.

Mixed feelings towards a charismatic creative genius who made home life a torment and the way their fractured family kept going are reasons enough to read this book. But another is just that Garber’s life has been so interesting: she witnessed the 1968 race riots and had a black boyfriend when interracial relationships were frowned upon; she was briefly the librarian for the Oceanics School, whose boat was taken hostage in Panama; and she dropped out of mythology studies at Harvard to become an acupuncturist. Don’t assume this will be a boring tome only for architecture buffs. It’s a masterful memoir for everyone. (Read via NetGalley on Nook)

My rating:

Florida by Lauren Groff

[William Heinemann (UK), 7th / Riverhead (USA), 5th]

My review is in today’s “Book Wars” column in Stylist magazine. Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. The narrator of “The Midnight Zone,” staying with her sons in a hunting camp 20 miles from civilization, ponders the cruelty of time and her failure to be sufficiently maternal, while the woman in “Flower Hunters” is so lost in an eighteenth-century naturalist’s book that she forgets to get Halloween costumes for her kids. A few favorites of mine were “Ghosts and Empties,” in which the narrator goes for long walks at twilight and watches time passing through the unwitting tableaux of the neighbors’ windows; “Eyewall,” a matter-of-fact ghost story; and “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness – it’s terrifying how precarious her life is at every step. (Proof copy)

My review is in today’s “Book Wars” column in Stylist magazine. Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. The narrator of “The Midnight Zone,” staying with her sons in a hunting camp 20 miles from civilization, ponders the cruelty of time and her failure to be sufficiently maternal, while the woman in “Flower Hunters” is so lost in an eighteenth-century naturalist’s book that she forgets to get Halloween costumes for her kids. A few favorites of mine were “Ghosts and Empties,” in which the narrator goes for long walks at twilight and watches time passing through the unwitting tableaux of the neighbors’ windows; “Eyewall,” a matter-of-fact ghost story; and “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness – it’s terrifying how precarious her life is at every step. (Proof copy)

Favorite lines:

“What had been built to seem so solid was fragile in the face of time because time is impassive, more animal than human. Time would not care if you fell out of it. It would continue on without you.” (from “The Midnight Zone”)

“The wind played the chimney until the whole place wheezed like a bagpipe.” (from “Eyewall”)

“How lonely it would be, the mother thinks, looking at her children, to live in this dark world without them.” (from “Yport”)

My rating:

The Most Beautiful Thing I’ve Seen: Opening Your Eyes to Wonder by Lisa Gungor

[Zondervan, 26th]

You’re most likely to pick this up if you enjoy Gungor’s music, but it’s by no means a band tell-all. The big theme of this memoir is moving beyond the strictures of religion to find an all-encompassing spirituality. Like many Gungor listeners, Lisa grew up in, and soon outgrew, a fundamentalist Christian setting. She bases the book around a key set of metaphors: the dot, the line, and the circle. The dot was the confining theology she was raised with; the line was the pilgrimage she and Michael Gungor embarked on after they married at 19; the circle was the more inclusive spirituality she developed after their second daughter, Lucie, was born with Down syndrome and required urgent heart surgery. Being mothered, becoming a mother and accepting God as Mother: together these experiences bring the book full circle. Barring the too-frequent nerdy-cool posturing (seven mentions of “dance parties,” and so on), this is a likable memoir for readers of spiritual writing by the likes of Sue Monk Kidd, Mary Oliver and Terry Tempest Williams. (Read via NetGalley on Kindle)

You’re most likely to pick this up if you enjoy Gungor’s music, but it’s by no means a band tell-all. The big theme of this memoir is moving beyond the strictures of religion to find an all-encompassing spirituality. Like many Gungor listeners, Lisa grew up in, and soon outgrew, a fundamentalist Christian setting. She bases the book around a key set of metaphors: the dot, the line, and the circle. The dot was the confining theology she was raised with; the line was the pilgrimage she and Michael Gungor embarked on after they married at 19; the circle was the more inclusive spirituality she developed after their second daughter, Lucie, was born with Down syndrome and required urgent heart surgery. Being mothered, becoming a mother and accepting God as Mother: together these experiences bring the book full circle. Barring the too-frequent nerdy-cool posturing (seven mentions of “dance parties,” and so on), this is a likable memoir for readers of spiritual writing by the likes of Sue Monk Kidd, Mary Oliver and Terry Tempest Williams. (Read via NetGalley on Kindle)

My rating:

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes

[Oneworld, 7th] – see my full review.

Ok, Mr Field by Katharine Kilalea

[Faber & Faber, 7th]

Mr. Field is a concert pianist whose wrist was shattered in a train crash. With his career temporarily derailed, there’s little for him to do apart from wander his Cape Town house, a replica of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, and the nearby coastal path. He also drives over to spy on his architect’s widow, with whom he’s obsessed. He’s an aimless voyeur who’s more engaged with other people’s lives than with his own – until a dog follows him home from a graveyard. This is a strangely detached little novel in which little seems to happen. Like Asunder by Chloe Aridjis and Leaving the Atocha Station by Ben Lerner, it’s about someone who’s been coasting unfeelingly through life and has to stop to ask what’s gone wrong and what’s worth pursuing. It’s so brilliantly written, with the pages flowing effortlessly on, that I admired Kilalea’s skill. Her descriptions of scenery and music are particularly good. In terms of the style, I was reminded of books I’ve read by Katie Kitamura and Henrietta Rose-Innes. (Proof copy from Faber Spring Party)

Mr. Field is a concert pianist whose wrist was shattered in a train crash. With his career temporarily derailed, there’s little for him to do apart from wander his Cape Town house, a replica of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, and the nearby coastal path. He also drives over to spy on his architect’s widow, with whom he’s obsessed. He’s an aimless voyeur who’s more engaged with other people’s lives than with his own – until a dog follows him home from a graveyard. This is a strangely detached little novel in which little seems to happen. Like Asunder by Chloe Aridjis and Leaving the Atocha Station by Ben Lerner, it’s about someone who’s been coasting unfeelingly through life and has to stop to ask what’s gone wrong and what’s worth pursuing. It’s so brilliantly written, with the pages flowing effortlessly on, that I admired Kilalea’s skill. Her descriptions of scenery and music are particularly good. In terms of the style, I was reminded of books I’ve read by Katie Kitamura and Henrietta Rose-Innes. (Proof copy from Faber Spring Party)

My rating:

This came out in the States (from Riverhead) back in early April, but releases here in the UK soon, so I’ve added it in as a bonus.

The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer

[Chatto & Windus, 7th]

An enjoyable story of twentysomethings looking for purpose and trying to be good feminists. To start with it’s a fairly familiar campus novel in the vein of The Art of Fielding and The Marriage Plot, but we follow Greer, her high school sweetheart Cory and her new friend Zee for the next 10+ years to see the compromises they make as ideals bend to reality. Faith Frank is Greer’s feminist idol, but she’s only human in the end, and there are different ways of being a feminist: not just speaking out from a stage, but also quietly living every day in a way that shows you value people equally. I have a feeling this would have meant much more to me a decade ago, and the #MeToo-ready message isn’t exactly groundbreaking, but I very much enjoyed my first taste of Wolitzer’s sharp, witty writing and will be sure to read more from her. This seems custom-made for next year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. (Free from publisher, for comparison with Florida in Stylist “Book Wars” column.)

An enjoyable story of twentysomethings looking for purpose and trying to be good feminists. To start with it’s a fairly familiar campus novel in the vein of The Art of Fielding and The Marriage Plot, but we follow Greer, her high school sweetheart Cory and her new friend Zee for the next 10+ years to see the compromises they make as ideals bend to reality. Faith Frank is Greer’s feminist idol, but she’s only human in the end, and there are different ways of being a feminist: not just speaking out from a stage, but also quietly living every day in a way that shows you value people equally. I have a feeling this would have meant much more to me a decade ago, and the #MeToo-ready message isn’t exactly groundbreaking, but I very much enjoyed my first taste of Wolitzer’s sharp, witty writing and will be sure to read more from her. This seems custom-made for next year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. (Free from publisher, for comparison with Florida in Stylist “Book Wars” column.)

My rating:

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.  Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.

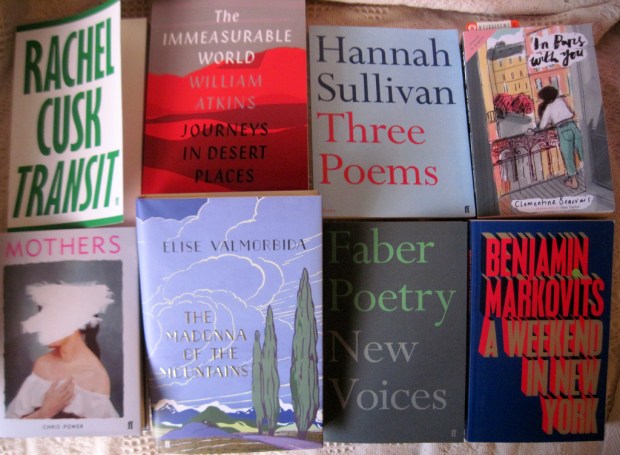

Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.  I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.