#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

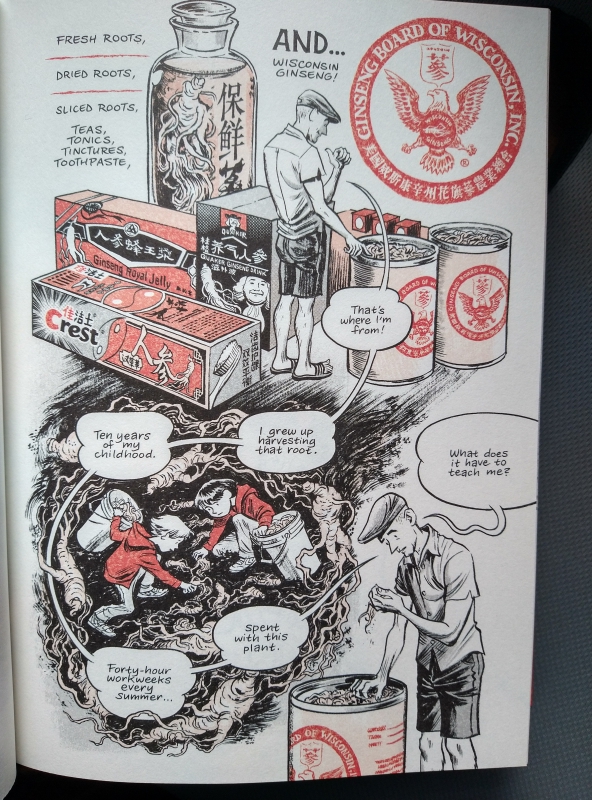

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

Library Checkout, August 2020 & #WITMonth 2020, Part II

I’ve been volunteering at my local library twice a week since the start of the month, shelving and picking books off the shelves to fulfill reservations. Every time I’m there I spot more titles to add to my online wish list. It’s been a convenient excuse to return and pick up books, including book group sets. I was first in the queue for some brand-new releases this month.

Have you been able to borrow more books lately? Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (which runs on the last Monday of every month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram (@bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout).

READ

- Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams

- Addition by Toni Jordan [book club choice]

- Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo (reviewed below)

SKIMMED

- Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash

- The Butterfly Isles: A Summer in Search of Our Emperors and Admirals by Patrick Barkham

- Water Ways: A Thousand Miles along Britain’s Canals by Jasper Winn

CURRENTLY READING

- Close to Where the Heart Gives Out: A Year in the Life of an Orkney Doctor by Malcolm Alexander

- A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive by Stephanie Land

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- Can You Hear Me? A Paramedic’s Encounters with Life and Death by Jake Jones

- Dear NHS: 100 Stories to Say Thank You, edited by Adam Kay

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

- What Have I Done? An Honest Memoir about Surviving Postnatal Mental Illness by Laura Dockrill

- How to Be Both by Ali Smith

- Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth

- The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Dependency by Tove Ditlevsen

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Persuasion by Jane Austen

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- The Hungover Games by Sophie Heawood

- Just Like You by Nick Hornby

- 33 Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong End of Medicine by David Jarrett

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Vesper Flights: New and Selected Essays by Helen Macdonald

- English Pastoral: An Inheritance by James Rebanks

- Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

- Dear Reader: The Comfort and Joy of Books by Cathy Rentzenbrink

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward

- The Courage to Care: A Call for Compassion by Christie Watson

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Apeirogon by Colum McCann – I only made it through the first 150 pages. A work that could have been very powerful if condensed instead sprawls into repetition and pretension. I still expect it to make the Booker shortlist, but not to win. I’ll add further thoughts closer to the time.

- That Reminds Me by Derek Owusu – I was expecting a memoir in verse about life in foster care; this is autofiction in dull fragments. I read the first 23 pages out of 113, waiting for it to get better.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston – I needed to make room for some new books on my account, so will request this at another time.

- Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell – I realized the subject matter didn’t draw me enough to read 500+ pages. So I passed it to my husband, a big Mitchell fan, and he read it happily, but mentioned that he didn’t find it compelling until about 2/3 through and he thought the combination of real-life and made-up figures (including from Mitchell’s previous oeuvre) was a bit silly.

- 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami – Again, I needed to make space on my card and was, unsurprisingly, daunted by the length of this 1,000+-page omnibus paperback. When I do try the novel, I’ll borrow it in its three separate volumes!

What appeals from my stacks?

My second choice for Women in Translation Month (after The Bitch by Pilar Quintana) was:

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo (2016)

[Translated from the Korean by Jamie Chang]

The title character is a sort of South Korean Everywoman whose experiences reveal the ways in which women’s lives are still constrained by that country’s patriarchal structures and traditions. She and her fellow female students and colleagues are subject to myriad microaggressions, from being served cafeteria lunches after the boys to being excluded from leadership of university clubs to having no recourse when security guards set up cameras in the female toilets at work. Jiyoung is wary of marriage and motherhood, afraid of derailing her budding marketing career, and despite her determination to do things differently she is disappointed at how much she has to give up when she has her daughter. “Her career potential and areas of interest were being limited just because she had a baby.”

The title character is a sort of South Korean Everywoman whose experiences reveal the ways in which women’s lives are still constrained by that country’s patriarchal structures and traditions. She and her fellow female students and colleagues are subject to myriad microaggressions, from being served cafeteria lunches after the boys to being excluded from leadership of university clubs to having no recourse when security guards set up cameras in the female toilets at work. Jiyoung is wary of marriage and motherhood, afraid of derailing her budding marketing career, and despite her determination to do things differently she is disappointed at how much she has to give up when she has her daughter. “Her career potential and areas of interest were being limited just because she had a baby.”

The prose is flat, with statistics about women’s lives in Korea unnaturally inserted in the text. Late on we discover there’s a particular reason for the clinically detached writing, but it’s not enough to fully compensate for a dull style. I also found the translation shaky in places, e.g. “She cautiously mentioned shop sales … to the mother who’d dropped by at home to make dinner” and “Jiyoung made it home safely on her boyfriend’s back, but their relationship didn’t.” I most liked Jiyoung’s entrepreneurial mother, who occasionally shows her feisty spirit: “The porridge shop was my idea, and I bought the apartment. And the children raised themselves. Yes, you’ve made it, but you didn’t do it all by yourself,” she says to her husband. “Run wild!” she exhorts Jiyoung, but the system makes that vanishingly difficult.

Books in Brief: Five I Loved Recently

Novels narrated by an octogenarian and an unborn child; memoirs about connection with nature and escaping an abusive relationship; and a strong poetry collection that includes some everyday epics: these five wildly different books are all 4-star reads I can highly recommend.

The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen, 83¼ Years Old

In this anonymous Dutch novel in diary form, Hendrik Groen provides a full reckoning of how 2013 went down in his Amsterdam old folks’ care home. He and five friends form the “Old But Not Dead” club and take turns planning exciting weekly outings. Much comic relief is provided by his incorrigibly tippling friend, Evert, and the arrival of Eefje makes late-life romance seem like a possibility for Hendrik. However, there’s no getting around physical decay: between them these friends suffer from incontinence, dementia, diabetic amputations and a stroke. By the time 2014 rolls around, their number will be reduced by one. Yet this is a tremendously witty and warm-hearted book, despite Hendrik’s sad family history. It’s definitely one for fans of A Man Called Ove – but I liked this more. A sequel from 85-year-old Hendrik came out this year in Dutch; I’ll be looking forward to the English translation.

In this anonymous Dutch novel in diary form, Hendrik Groen provides a full reckoning of how 2013 went down in his Amsterdam old folks’ care home. He and five friends form the “Old But Not Dead” club and take turns planning exciting weekly outings. Much comic relief is provided by his incorrigibly tippling friend, Evert, and the arrival of Eefje makes late-life romance seem like a possibility for Hendrik. However, there’s no getting around physical decay: between them these friends suffer from incontinence, dementia, diabetic amputations and a stroke. By the time 2014 rolls around, their number will be reduced by one. Yet this is a tremendously witty and warm-hearted book, despite Hendrik’s sad family history. It’s definitely one for fans of A Man Called Ove – but I liked this more. A sequel from 85-year-old Hendrik came out this year in Dutch; I’ll be looking forward to the English translation.

The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy

By Michael McCarthy

An environmental journalist for the UK’s Independent, McCarthy offers a personal view of how the erstwhile abundance of the natural world has experienced a dramatic thinning, even just in England in his lifetime. He gives both statistical and anecdotal evidence for that decline; as a case study he discusses the construction of a sea wall at Saemangeum in South Korea, responsible for decimating a precious estuary habitat for shorebirds. As if to balance his pessimism about the state of the world, McCarthy remembers singular natural encounters that filled him with joy and wonder – first discovering birdwatching as a lad near Liverpool, seeing a morpho butterfly in South America – but also annual displays that rekindle his love of life: the winter solstice, the arrival of cuckoos, and bluebells. This memoir is more sentimental than I expected from an English author, but I admire his passion and openness.

An environmental journalist for the UK’s Independent, McCarthy offers a personal view of how the erstwhile abundance of the natural world has experienced a dramatic thinning, even just in England in his lifetime. He gives both statistical and anecdotal evidence for that decline; as a case study he discusses the construction of a sea wall at Saemangeum in South Korea, responsible for decimating a precious estuary habitat for shorebirds. As if to balance his pessimism about the state of the world, McCarthy remembers singular natural encounters that filled him with joy and wonder – first discovering birdwatching as a lad near Liverpool, seeing a morpho butterfly in South America – but also annual displays that rekindle his love of life: the winter solstice, the arrival of cuckoos, and bluebells. This memoir is more sentimental than I expected from an English author, but I admire his passion and openness.

Nutshell

By Ian McEwan

My seventh McEwan novel and one of his strongest. Within the first few pages, I was utterly captivated and convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Provided you suspend disbelief a bit to accept he can see/hear/surmise everything that happens – the most tedious passages are those where McEwan tries to give more precise justification for his narrator’s observations – the plot really works. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this fetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his whole future depends on it.

My seventh McEwan novel and one of his strongest. Within the first few pages, I was utterly captivated and convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Provided you suspend disbelief a bit to accept he can see/hear/surmise everything that happens – the most tedious passages are those where McEwan tries to give more precise justification for his narrator’s observations – the plot really works. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this fetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his whole future depends on it.

Favorite line: “I have lungs but not air to shout a warning or weep with shame at my impotence.”

How Snow Falls

By Craig Raine

One of the few best poetry collections I’ve read this year. It contains nary a dud and is a good one to sink your teeth into – it’s composed of just 20 poems, but several are in-depth epics drawn from everyday life and death. Two elegies, to a dead mother and a former lover, are particularly strong. I loved the mixture of clinical and whimsical vocabulary in “I Remember My Mother” as the poet charts the transformation from person to corpse. “Rashomon” is another stand-out, commissioned as an opera and inspired by the short story “In a Grove” by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. In couplets with a flexible rhyme scheme, the poem alternates the perspectives of a bandit, a captive husband, his raped wife, and the woodcutter who becomes an unwilling observer. Alliteration is noteworthy throughout the collection, but here produces one of my favorite lines: “Sweet cedar chips were spurting in the gloom like sparks.”

One of the few best poetry collections I’ve read this year. It contains nary a dud and is a good one to sink your teeth into – it’s composed of just 20 poems, but several are in-depth epics drawn from everyday life and death. Two elegies, to a dead mother and a former lover, are particularly strong. I loved the mixture of clinical and whimsical vocabulary in “I Remember My Mother” as the poet charts the transformation from person to corpse. “Rashomon” is another stand-out, commissioned as an opera and inspired by the short story “In a Grove” by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. In couplets with a flexible rhyme scheme, the poem alternates the perspectives of a bandit, a captive husband, his raped wife, and the woodcutter who becomes an unwilling observer. Alliteration is noteworthy throughout the collection, but here produces one of my favorite lines: “Sweet cedar chips were spurting in the gloom like sparks.”

Land of Enchantment

By Leigh Stein

Stein tells of her abusive relationship with Jason, a reckless younger man with whom she moved to New Mexico. The memoir mostly toggles between their shaky attempt at a functional relationship in 2007 and learning about his death in a motorcycle accident in 2011. Even though they’d drifted apart, Jason’s memory still had power over her. Breaking free from him meant growing up at last and taking responsibility for her future. You might call this a feminist coming-of-age narrative, though that makes it sound more strident and formulaic than it actually is. I admired the skipping around in time, and especially a late chapter in the second person. I also enjoyed how New Mexico provides a metaphorical as well as a literal setting; Stein weaves in references to Georgia O’Keeffe’s art and letters to put into context her own search to become a self-sufficient artist.

Stein tells of her abusive relationship with Jason, a reckless younger man with whom she moved to New Mexico. The memoir mostly toggles between their shaky attempt at a functional relationship in 2007 and learning about his death in a motorcycle accident in 2011. Even though they’d drifted apart, Jason’s memory still had power over her. Breaking free from him meant growing up at last and taking responsibility for her future. You might call this a feminist coming-of-age narrative, though that makes it sound more strident and formulaic than it actually is. I admired the skipping around in time, and especially a late chapter in the second person. I also enjoyed how New Mexico provides a metaphorical as well as a literal setting; Stein weaves in references to Georgia O’Keeffe’s art and letters to put into context her own search to become a self-sufficient artist.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

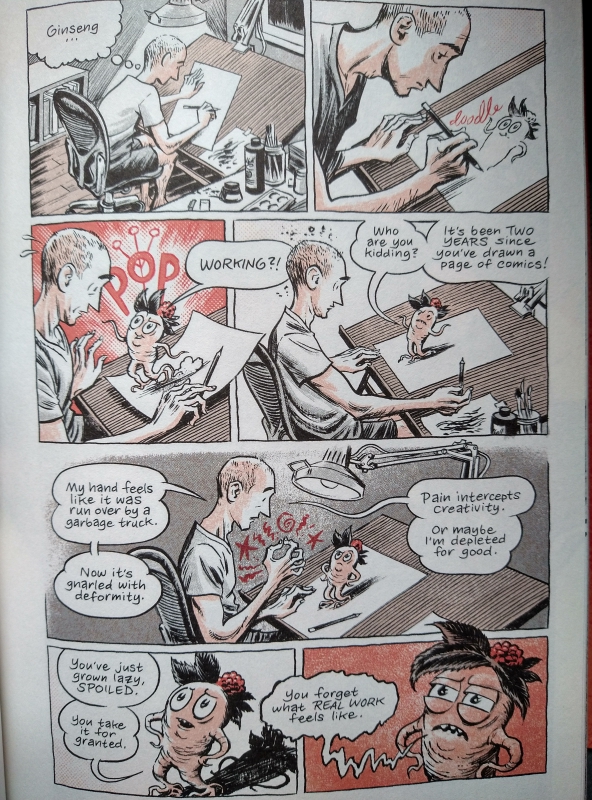

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress.

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress. Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of

Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of  The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.

The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.  A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.

A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.

Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.

Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.  The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.

The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.  Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.

Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.  Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.

Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.  Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.

Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.  The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.  The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.