20 Books of Summer, 19–20: Emily St. James and Abraham Verghese

Going out on a high! My last three books for the challenge (also including Beautiful Ruins) were particularly great, just the sort of absorbing and rewarding reading that I wish I could guarantee for all of my summer selections.

Woodworking by Emily St. James (2025)

Colloquially, “woodworking” is disappearing in plain sight; doing all you can to fade into the woodwork. Erica has only just admitted her identity to herself, and over the autumn of 2016 begins telling others she’s a woman – starting with her ex-wife Constance, who is now pregnant by her fiancé, John. To everyone else, Erica is still Mr. Skyberg, a 35-year-old English teacher at Mitchell High involved in local amateur dramatics. When Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, Abigail Hawkes, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed new mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. Abigail lives with her adult sister instead, and gains an unexpected surrogate family via her boyfriend Caleb, a Korean adoptee whose mother, Brooke Daniels, is directing Our Town. Brooke is surprisingly supportive given that she attends Isaiah Rose’s megachurch.

As Trump/Pence signs proliferate, a local election is heating up, too: Pastor Rose is running for State Congress on the Republican ticket, opposed by Helen Swee. Erica befriends Helen and becomes faculty advisor for the school’s Democrat club (which has all of two members: Abigail and her Leslie Knope-like friend Megan). The plot swings naturally between the personal and political, emphasizing how the personal business of 1% of the population has been made into a political football. Chapters alternate between Abigail in first person and Erica in third. The characters feel utterly real and the dialogue is as genuine as the narrative voices. The support group Erica and Abigail attend presents a range of trans experiences based on when one came of age. Some are still deep undercover. There’s a big reveal I couldn’t quite accept, though I can see its purpose. It’s particularly effective how St. James lets second- and third-person narration shade into first as characters accept their selves. Grey rectangles cover up deadnames all but once, making the point that even allies can get it wrong.

This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message to convey. It reminded me a lot of Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey but also had the flavour of classic Tom Perrotta (Election). In the Author’s Note, St. James writes, “They say the single greatest determinant of whether someone will support and affirm trans people is if they know a trans person.” I feel lucky to count three trans people among my friends. It’s impossible to make detached pronouncements about bathrooms and slippery slopes if you care about people whose rights and very existence are being undermined. We should all be reading books by and about trans women. (New purchase from Bookshop.org) ![]()

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (2023)

All too often, I shy away from doorstoppers because they seem like too much of a time commitment. Why read 715 pages in one novel when I could read 3.5 of 200 pages each? Yet there’s something special about being lost in the middle of a great big book and trusting that wherever the story goes will be worthwhile. I let this review copy languish on the shelf for over TWO YEARS when I should have known that the author of the amazing Cutting for Stone couldn’t possibly let me down. Verghese’s second novel is very much in the same vein: a family saga that spans decades and in every generation focuses on medical issues. Verghese is a practicing doctor as well as a Stanford professor and you can tell he glories in the details of hand and brain surgeries, disability and rare diseases – and luckily, so do I.

Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but the focus is always on one family in Kerala, starting in 1900 when a 12-year-old girl is brought to the Parambil estate for her arranged marriage to a 40-year-old widower. One day she will be Big Ammachi, the matriarch of a family with a mysterious Condition: In every generation, someone drowns. As a result, they all avoid water, even if it requires going hours out of their way. Her son Philipose longs to be a scholar, but is so hard of hearing that his formal education is cut short. He becomes a columnist in a local newspaper and marries Elsie, a spirited artist. Their daughter, Mariamma, trains as a doctor. In parallel, we follow the story of Digby Kilgour, a Glaswegian surgeon whose career takes him to India. Through Digby and Mariamma’s interactions with colleagues, we watch colonial incompetence and sexism play out. Addiction and suicide recur across the years. Destiny and choice lock horns. I enjoyed the window onto the small community of St. Thomas Christians and felt fond of all the characters, including Damodaran the elephant. It’s also really clever how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between a mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intellectual soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary. ![]()

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the proof copy for review.

I read 10 of the books I selected in my initial planning post. I’m pleased that I picked off a couple of long-neglected review copies and several recent purchases. The rest were substituted at whim. There were two duds, but the overall quality was high, with 10 books I rated 4 stars or higher! Along with the above and Beautiful Ruins, Pet Sematary and Storm Pegs were overall highlights. I also managed to complete a row on the Bingo card, a fun add-on. And, bonus: I cleared 7 books from my shelves by reselling or giving them away after I read them.

Three on a Theme: Armchair Travels at the Italian Coast (Rachel Joyce, Sarah Moss and Jess Walter – #18 of 20 Books)

I’ve done a lot of journeying through Italy’s lakes and islands this summer. Not in real life, thank goodness – it would be far too hot! – but via books. I started with the Moss, then read the Joyce, and rounded off with the Walter, a book that had been on my TBR for 12 years and that many had heartily recommended, so I was delighted to finally experience it for myself.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce (2025)

Joyce has really upped her game. I’ve somehow read all of her books though I often found them, from Harold Fry onward, disappointingly sentimental and twee. But with this she’s entering the big leagues, moving into the more expansive, elegant and empathetic territory of novels by Anne Enright (The Green Road), Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition), Maggie O’Farrell (Instructions for a Heatwave) and Tom Rachman (The Italian Teacher). It’s the story of four siblings, initially drawn together and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s death. Despite weighty themes of alcoholism, depression and marital struggles, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read.

Vic Kemp, the title figure, was a larger-than-life, womanizing painter whose work divided critics. After his first wife’s early death from cancer, he raised three daughters and a son with the help of a rotating cast of nannies (whom he inevitably slept with). At 76 he delivered the shocking news that he was marrying again: Bella-Mae, an artist in her twenties – much younger than any of his children. They moved from London to his second home in Italy just weeks before he drowned in Lake Orta. Netta, the eldest daughter, is sure there’s something fishy; he knew the lake so well and would never have gone out for a swim with a mist rolling in. Did Bella-Mae kill him for his money? And where is his last painting? Funny how waiting for an autopsy report and searching for a new will and carping with siblings over the division of belongings can ruin what should be paradise.

The interactions between Netta, Susan, Goose (Gustav) and Iris, plus Bella-Mae and her cousin Laszlo, are all flawlessly done, and through flashbacks and surges forward we learn so much about these flawed and flailing characters. The derelict villa and surrounding small town are appealing settings, and there are a lot of intriguing references to food, fashion and modern art.

My only small points of criticism are that Iris is less fleshed out than the others (and her bombshell secret felt distasteful), and that Joyce occasionally resorts to delivering some of her old obvious (though true) messages through an omniscient narrator, whereas they could be more palatable if they came out organically in dialogue or indirectly through a character’s thought process. Here’s an example: “When someone dies or disappears, we can only tell stories about what might have been the case or what might have happened next.” (One I liked better: “There were some things you never got over. No amount of thinking or talking would make them right: the best you could do was find a way to live alongside them.”) I also don’t think Goose would have been able to view his father’s body more than two months after his death; even with embalming, it would have started to decay within weeks.

You can tell that Joyce got her start in theatre because she’s so good at scenes and dialogue, and at moving people into different groups to see what they’ll do. She’s taken the best of her work in other media and brought it to bear here. It’s fascinating how Goose starts off seeming minor and eventually becomes the main POV character. And ending with a wedding (good enough for a Shakespearean comedy) offers a lovely occasion for a potential reconciliation after a (tragi)comic plot. More of this calibre, please! (Public library) ![]()

Ripeness by Sarah Moss (2025)

One sneaky little line, “Ripeness, not readiness, is all,” a Shakespeare mash-up (“Ripeness is all” is from King Lear vs. “the readiness is all” is from Hamlet), gives a clue to how to understand this novel: As a work of maturity from Sarah Moss, presenting life with all its contradictions and disappointments, not attempting to counterbalance that realism with any false optimism. What do we do, who will we be, when faced with situations for which we aren’t prepared?

Now that she’s based in Ireland, Moss seems almost to be channelling Irish authors such as Claire Keegan and Maggie O’Farrell. The line-up of themes – ballet + sisters + ambivalent motherhood + the question of immigration and belonging – should have added up to something incredible and right up my street. While Ripeness is good, even very good, it feels slightly forced. As has been true with some of Moss’s recent fiction (especially Summerwater), there is the air of a creative writing experiment. Here the trial is to determine which feels closer, a first-person rendering of a time nearly 60 years ago, or a present-tense, close-third-person account of the now. [I had in mind advice from one of Emma Darwin’s Substack posts: “What you’ll see is that ‘deep third’ is really much the same as first, in the logic of it, just with different pronouns: you are locking the narrative into a certain character’s point-of-view, but you don’t have a sense of that character as the narrator, the way you do in first person.” Except, increasingly as the novel goes on, we are compelled to think about Edith as a narrator, of her own life and others’.

In the current story line, everyone in rural West Ireland seems to have come from somewhere else (e.g. Edith’s lover Gunter is German). “She’s going to have to find a way to rise above it, this tribalism,” Edith thinks. She’s aghast at her town playing host to a small protest against immigration. Fair enough, but including this incident just seems like an excuse for some liberal handwringing (“since it’s obvious that there is enough for all, that the problem is distribution not supply, why cannot all have enough? Partly because people like Edith have too much.”). The facts of Maman being French-Israeli and having lost family in the Holocaust felt particularly shoehorned in; referencing Jewishness adds nothing. I also wondered why she set the 1960s narrative in Italy, apart from novelty and personal familiarity. (Teenage Edith’s high school Italian is improbably advanced, allowing her to translate throughout her sister’s childbirth.)

Though much of what I’ve written seems negative, I was left with an overall favourable impression. Mostly it’s that the delivery scene and the chapters that follow it are so very moving. Plus there are astute lines everywhere you look, whether on dance, motherhood, or migration. It may simply be that Moss was taking on too much at once, such that this lacks the focus of her novellas. Ultimately, I would have been happy to have just the historical story line; the repeat of the surrendering for adoption element isn’t necessary to make any point. (I was relieved, anyway, that Moss didn’t resort to the cheap trick of having the baby turn out to be a character we’ve already been introduced to.) I admire the ambition but feel Moss has yet to return to the sweet spot of her first five novels. Still, I’m a fan for life. (Public library) ![]()

#18 of my 20 Books of Summer

(Completing the second row on the Bingo card: Book set in a vacation destination)

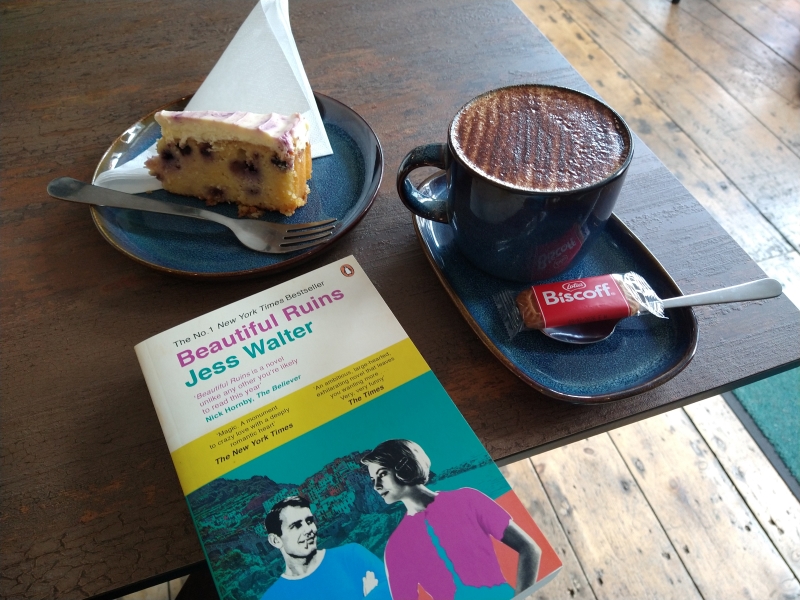

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I’m relieved to report that Beautiful Ruins lived up to everyone’s acclaim – and my own high expectations after enjoying Walter’s So Far Gone, which I reviewed for BookBrowse earlier in the summer. I was immediately captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. With refreshing honesty, he’s dubbed the place “Hotel Adequate View.” In April 1962, he’s attempting to build a cliff-edge tennis court when a boat delivers beautiful, dying American actress Dee Moray. It soon becomes clear that her condition is nothing nine months won’t fix and she’s been dumped here to keep her from meddling in the romance between the leads in Cleopatra, filming in Rome. In the present day, an elderly Pasquale goes to Hollywood to find out whatever happened to Dee.

A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime masterpiece, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in that summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. True to the tone of a novel about regret, failure and shattered illusions, Walter doesn’t tie everything up neatly, but he does offer a number of the characters a chance at redemption. This felt to me like a warmer and more timeless version of A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are so many great scenes, none better than Richard Burton’s drunken visit to Porto Vergogna, which had me in stitches. Fantastic. (Hungerford Bookshop – 40th birthday gift from my husband from my wish list) ![]()

#WITMonth, II: Bélem, Blažević, Enríquez, Lebda, Pacheco and Yu (#17 of 20 Books)

Catching up with my Women in Translation month coverage, which concluded (after Part I, here) with five more short novels ranging from historical realism to animal-oriented allegory, plus a travel book.

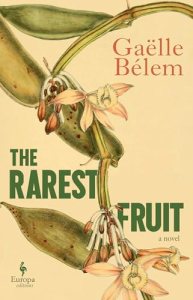

The Rarest Fruit, or The Life of Edmond Albius by Gaëlle Bélem (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Hildegarde Serle]

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

With thanks to Europa Editions, who sent an advanced e-copy for review.

In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Croatian by Anđelka Raguž]

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

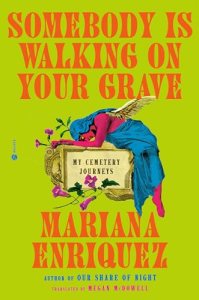

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez (2013; 2025)

[Translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell]

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones]

Like the Blažević, this is an impressionistic, pastoral work that contrasts vitality and decay in short chapters of one to three pages. The narrator is a young woman staying in her grandmother’s house and caring for her while she is dying of cancer; “now is not the time for life. Death – that’s what fills my head. I’m at its service. Grandma is my child. I am my grandmother’s mother. And that’s all right, I think.” The house has just four inhabitants – the narrator, Grandma Róża, Grandpa, and Ann – and seems permeable: to the cold, to nature. Animals play a large role, whether pets, farmed or wild. There’s Danube the hound, the cows delivered to the nearby slaughterhouse, and a local vixen with whom the narrator identifies.

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

In all three Linden Editions books I’ve read, the translator’s afterword has been particularly illuminating. I thought I was missing something, but Lloyd-Jones reassured me it’s unclear who Ann is: sister? friend? lover? (I was sure I spotted some homoerotic moments.) Lloyd-Jones believes she’s the mirror image of the narrator, leaning toward life while the narrator – who has endured sexual molestation and thyroid problems – tends towards death. The animal imagery reinforces that dichotomy.

The narrator and Ann remark that it feels like Grandma has been ill for a million years, but they also never want this time to end. The novel creates that luminous, eternal present. It was the best of this bunch.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews:

Pandora by Ana Paula Pacheco (2023; 2025)

[Translated from Portuguese by Julia Sanches]

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

#17 of my 20 Books of Summer:

Invisible Kitties by Yu Yoyo (2021; 2024)

[Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang]

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

I’m really pleased with myself for covering a total of 8 books for this challenge, each one translated from a different language!

Which of these would you read?

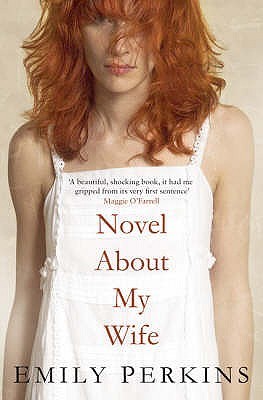

Literary Wives Club: Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins (2008)

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

“If I could build her again using words, I would,” he opens, but that promising start just leads into paragraphs of physical description. Bare facts, such as that Ann was from Sydney and created radiation masks for cancer patients in a hospital, are hardly revealing. We mostly know Ann through her delusions. In her late thirties, when she was three months pregnant with their son Arlo, she was caught in an underground train derailment. Thereafter, she increasingly fell victim to paranoia, believing that she was being stalked and that their house was infested. We’re invited to speculate that pregnancy exacerbated her mental health issues and that postpartum psychosis may have had something to do with her death.

I mostly skimmed the novel, so I may have missed some plot points, but what stood out to me were Tom’s unpleasant depictions of women and complaints about his faltering career. (He’s envious of a new acquaintance, Simon, who’s back and forth to Hollywood all the time for successful screenwriting projects.) Interspersed are seemingly pointless excerpts from Tom’s screenplay about a trip he and Ann took to Fiji. I longed for the balance of another perspective. This had a bit of the flavour of early Maggie O’Farrell, but none of the warmth. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Being generous to Perkins, perhaps the very point she was trying to make is that it’s impossible to get outside of one’s own perspective and understand what’s going on with a spouse, especially one who has mental health struggles. Had Tom been more attentive and supportive, might things have ended differently?

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is on a break this month.)

Coming up next, in December: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

20 Books of Summer, 11–12 (Victoriana): Edward Carey & George Grossmith

Neither of these appeared on my initial list, but I thought a middle-grade novel and a classic would be good for variety. Though I have an MA in Victorian Literature, I don’t often read from the period anymore because I’m allergic to wordy triple-deckers, so it was a delight to encounter something short and lighthearted. I’ve always been partial to a contemporary Victorian pastiche, though.

Heap House (Iremonger, #1) by Edward Carey (2013)

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

Carey’s trademark twisted combination of Dickensian charm and Gothic gloom is certainly on display here. All the other names are slightly off-kilter: Rosamud, Moorcus, Aliver, Pinalippy and so on. I laughed out loud at a passage about the dubious purpose of doilies. Little truly won me over, but all my experiences with Carey’s work since then (also including The Swallowed Man, B: A Year in Plagues and Pencils, and Edith Holler) have been a slight letdown. This was highly readable and I galloped through the midsection, but I found the whole thing overlong; I’m undecided about reading the other books, though they do have higher average ratings on Goodreads. I got the second, Foulsham, from the Little Free Library and it’s significantly shorter. Shall I continue? (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith; illus. Weedon Grossmith (1892)

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

Originally serialized in Punch, the book is in short entries of one paragraph to a few pages, recounting the Pooters’ first 15 months in their new home. Events range from the mundane – home repairs and decoration – to the great excitement of being invited to the mayor’s ball. Charles and Carrie’s young adult son, Lupin (surely a partial inspiration for Roger Mortimer’s Dear Lupin and its sequels?), who comes back to live with them partway through, is a feckless bounder always being taken in by new money-making schemes and unsuitable ladies. Charles hopes to find Lupin steady employment and steer him away from his infatuation with Daisy Mutlar.

It’s well worth reading for its own sake, but also for the window onto daily Victorian life, including things that aren’t always recorded, such as fashion and slang. And it’s clever how Pooter’s pretensions get punctured by the others around him: longsuffering Carrie (“He tells me his stupid dreams every morning nearly”), insolent Lupin (“Look here, Guv.; excuse me saying so, but you’re a bit out of date”), and testy Gowing – that’s right, the neighbours are named Cummings and Gowing (“I would add, you’re a bigger fool than you look, only that’s absolutely impossible”). All very amusing. (Free from mall bookshop c. 2020) ![]()

Never fear, I’m still on track to finish the challenge by the 31st!

#WITMonth, Part I: Susanna Bissoli, Jente Posthuma and More

I’m starting off my Women in Translation month coverage with two short novels: one Italian and one Dutch; both about women navigating loss, family relationships, physical or mental illness, and the desire to be a writer.

Struck by Susanna Bissoli (2024; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Georgia Wall]

Vera has been diagnosed a second time with breast cancer – the same disease that felled her mother a decade ago. “I’m fed up with feeling like a problem to be taken care of,” she thinks. Even as her treatment continues, she determines to find routes to a bigger life not defined by her illness. Writing is the solution. When she moves in with her grouchy octogenarian father, Zeno Benin, she discovers he’s secretly written a novel, A Lucky Man. The almost entirely unpunctuated document is handwritten across 51 notebooks Vera undertakes to type up and edit alongside her father as his health declines.

At the same time, she becomes possessed by the legend of local living ‘saint’ Annamaria Bigani, who has been visited multiple times by the Virgin Mary and learned her date of death. Wondering if there is a story here that she needs to tell, Vera interviews Bigani, then escapes to Greece for time and creative space. “Do they save us, stories? Or is it our job to save them? I believe writing that story, day in and day out for years, saved my father’s life. But I’m sorry, I don’t have time to save his story: I need to write my own. The saint, or so I thought.” In the end, we learn, Struck – the very novel we are reading – is Vera’s book.

The title comes from a scientific study conducted on people struck by lightning at a country festival in France. How did they survive, and what were the lasting effects? The same questions apply to Vera, who avoids talking about her cancer but whose relationship with her sister Nora is still affected by choices made while their mother was alive. There are many delightful small conversations and incidents here, often involving Vera’s niece Alice. Vera’s relationship with Franco, a doctor who works with asylum seekers, is a steady part of the background. A translator’s afterword helped me understand the thought that went into how to reproduce Vera and others’ use of dialect (La Bassa Veronese vs. standard Italian) through English vernacular – so Vera and her sister say “Mam” and her father uses colourful idioms.

Though I know nothing of Bissoli’s biography, this second novel has the feeling of autofiction. Despite its wrenching themes of illness and the inevitability of death, it’s a lighthearted family story with free-flowing prose that I can enthusiastically recommend to readers of Elizabeth Berg and Catherine Newman.

This was my introduction to new (est. 2023) independent publisher Linden Editions, which primarily publishes literature in translation. I have two more of their books underway for another WIT Month post later this month. And a nice connection is that I corresponded with translator Georgia Wall when she was the publishing manager for The Emma Press.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

& Reviewed for Foreword Reviews a couple of years ago:

What I Don’t Want to Talk About by Jente Posthuma (2020; 2023)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

Both featured an unnamed narrator and a similar sense of humor. I concluded that Posthuma excels at exploring family dynamics and the aftermath of bereavement.

I got caught out when I reviewed The Appointment, too: Volckmer doesn’t technically count towards this challenge because she writes in English (and lives in London), but as she’s German, I’m adding in a teaser of my review as a bonus. Oddly, this novella did first appear in another language, French, in 2024, under the title Wonderf*ck. [The full title below was given to the UK edition.]

Calls May Be Recorded [for Training and Monitoring Purposes] by Katharina Volckmer (2025)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

20 Books of Summer, 9–10: Leave the World Behind & Leaving Atlanta

Halfway there! And I’m doing better than it might appear in that I’m in the middle of another 7 books and just have to decide what the final 3 will be. This was a sobering but satisfying pair of novels in which race and class play a part but the characters are ultimately helpless in the face of disasters and violence. Both: ![]()

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam (2020)

The title heralds a perfect holiday read, right? A New York City couple, Amanda and Clay, have rented a secluded vacation home in Long Island with their teenagers, Archie and Rose, and plan on a week of great beach weather and mild hedonism: food, drink, secret cigarettes, a hot tub, maybe some sex. But late on the first night there’s a knock on the door from the owners, sixtysomething Black couple Ruth and G. H. Something is going on; although the house still has power, all phone and Internet services have gone down. Rather than return to a potentially chaotic city, the older couple set course for their country retreat to hunker down. George is in finance and believes money solves everything, so he offers Amanda and Clay $1000 cash for the inconvenience of having their holiday interrupted.

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

This was a book club read and one of the most divisive I can remember. I was among the few who thought it gripping, intriguing, and even genuinely frightening. Others found the characters unlikable, the plot implausible or silly, and the writing heavy-handed. Alam is definitely poking fun at privileged bougie families. He draws attention to the author as puppet-master, inserting shrewd hints of what is occurring elsewhere or will soon befall certain characters. Some passages skirt pomposity with their anaphora and rhetorical questioning. Alliteration, repetition, and stark pronouncements make the prose almost baroque in places. Alam’s style is theatrical, even arch, but it suits the premonitory tone. I admired how he constantly upends genre expectations, moving from literary fiction to domestic drama to dystopia to magic realism to horror. The stuff of nightmares – being naked in front of strangers, one’s teeth falling out – becomes real, or at least real in the world of the book. The reminder is that we are never as in control as we think we are; always, disasters are unfolding. What will we do, and who will we be, as the inevitable unfolds?

You demanded answers, but the universe refused. Comfort and safety were just an illusion. Money meant nothing. All that meant anything was this—people, in the same place, together. This was what was left to them.

Absorbing, timely, controversial: read it! (Free from a neighbour)

Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones (2002)

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Even as their school is making news headlines, the children’s concerns are perennial adolescent ones: how to avoid bullying, who to sit with at lunch, how to be friendly yet not falsely encourage members of the opposite sex. And at home, all three struggle with an absent or overbearing father. At age 11, these kids are just starting to realize that their parents aren’t perfect and might not be able to keep them safe. I especially warmed to Octavia’s voice, even as her story made my heart ache: “cussing at myself for being too stupid to see that nothing lasts. That people get away from you like a handful of sweet smoke.” I preferred this offbeat, tender coming-of-age novel to Silver Sparrow and would place it on a par with An American Marriage. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

The Single Hound by May Sarton (1938)

I spotted that the 30th anniversary of May Sarton’s death was coming up, so decided to read an unread book of hers from my shelves in time to mark the occasion. Today’s the day: she died on July 16, 1995 in York, Maine. Marcie of Buried in Print joined me for a buddy read (her review). I was drawn by the title, which comes from an Emily Dickinson quote. It’s the ninth Sarton novel I’ve read and, while in general I find her nonfiction more memorable than her fiction, this impressionistic debut novel was a solid read. It was clearly inspired by Virginia Woolf’s work and based on Sarton’s memories of her time on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

the three together made a complete world.

Was this life? This slow penetration of experience until nothing had been left untasted, unexplored, unused — until the whole of one’s life became a fabric, a tapestry with a pattern? She could not see the pattern yet.

tea was opium to them both, the time when the past became a soft pleasant country of the imagination, lost its bitterness, ceased to devour, and in some tea-inspired way nourished them.

Part II felt to me like a strange swerve into the story of Mark Taylor, an aspiring English writer who falls in love with a married painter named Georgia Manning. Their flirtation, as soon through the eyes of a young romantic like Mark, is monolithic, earth-shattering, but to readers is more of a clichéd subplot. In the meantime, Mark sticks to his vow of going on a pilgrimage to Belgium to meet Jean Latour, the poet whose work first inspired him. Part III brings the two strands together in an unexpected way, as Mark gains clarity about his hero and his potential future with Georgia, though cleverer readers than I may have been able to predict it – especially if they heeded the Brontë connection.

It was rewarding to spot the seeds of future Sarton themes here, such as discovering the vocation of teaching (The Small Room) and young people meeting their elder role models and soliciting words of wisdom on how to live (Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing). Through Doro, Sarton also expresses trust in poetry’s serendipitous power. “This is why one is a poet, so that some day, sooner or later, one can say the right thing to the right person at the right time.” I enjoyed my time with the Little Owls but mostly viewed this as a dress rehearsal for later, more mature work. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent  I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.