June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Others Like Me: The Lives of Women without Children by Nicole Louie

I’ve read quite a lot about matrescence and motherhood so far this year, and I value these women authors’ perspectives on their experiences. There is much that resonates with me as I look back to my relationships with my parents and observe how my sister, brother-in-law and friends are raising their children. Yet as I read of the joys and struggles of parenthood, I do sometimes think, what about the rest of us? That’s the question that drove Nicole Louie to write this impassioned book, which combines the strengths of an oral history, a group biography and a fragmented memoir. Like me, she was in search of role models, and found plenty of them – first on the library shelves and then in daily life by interviewing women she encountered through work or via social media.

The 14 Q&As, shaped into first-person narratives, are interspersed with Louie’s own story, creating a chorus of voices advocating for women’s freedom. The particulars of their situations vary widely. A Venezuelan graphic designer with MS doesn’t want to have a baby to try to fill a perceived lack. A blind Canadian writer hopes for children but knows it may be too complicated on her own. A Ghanaian asexual woman confronts her culture’s traditional expectations of woman. A British nurse in her sixties is philosophical about not having a long-term relationship at the right time, and focuses instead on the thousands of people she’s been able to care for.

The subjects come from Iceland, Peru, the Isle of Man; they are undecided, living with illness or disability, longing but unpartnered, or utterly convinced that motherhood is not for them. Their reasons are logical, psychological, personal and/or environmental, and so many of their conclusions rang true for me:

I just want to make the most of what’s here now instead of always having to long for something else I don’t already have.

I have this strong core intent to be useful to society. To channel as much energy into it as I would put into raising two children … You can’t experience everything available to you in life. So you make choices, and you decide which paths to take and which ones to leave behind without trying. And that’s okay. What’s important is to move forward with intent.

Louie herself has an interesting background: she’s Brazilian but has lived in Sweden, the UK and Ireland. Her work as a copywriter and translator has taken her behind the scenes in training AI. She first had to give serious thought to the question of becoming a mother in 2009, when it became an issue in her first marriage. But, really, she’d known for a long time that it didn’t appeal to her – at age six she was given a doll whose tummy opened to reveal a baby and quickly exchanged that toy for another. A late diagnosis of PCOS and a complicated relationship with her own mother only reinforced a clear conviction.

Other works that I’ve encountered on childlessness, such as Childless Voices by Lorna Gibb (2019) and No One Talks about This Stuff: Twenty-Two Stories of Almost Parenthood, ed. Kat Brown (2024), are heavily weighted towards infertility. Here the spotlight is much more on being childfree, although the blurb is inclusive, speaking of “women who are not mothers by choice, infertility, circumstance or ambivalence.” (I love the inclusion of that final word.)

“Motherhood as the epicentre of women’s lives was all I’d ever witnessed” via her mother and grandmother, Louie writes, so finding examples of women living differently was key for her. As readers, then, we have the honour of watching her life, her thinking and the book all take shape simultaneously in the narrative. A lovely point to mention is that Molly Peacock (The Analyst and A Friend Sails in on a Poem) mentored her throughout the composition process.

Intimate and empathetic, Others Like Me is also elegantly structured, with layers of stories that reflect diversity and the intersectionality of challenges. This auto/biographical collage of life without children will be reassuring for many, and a learning opportunity for others. I’m so glad it exists.

With thanks to Nicole Louie and Dialogue Books for the proof copy for review.

Buy Others Like Me from Bookshop.org in the UK [affiliate link]

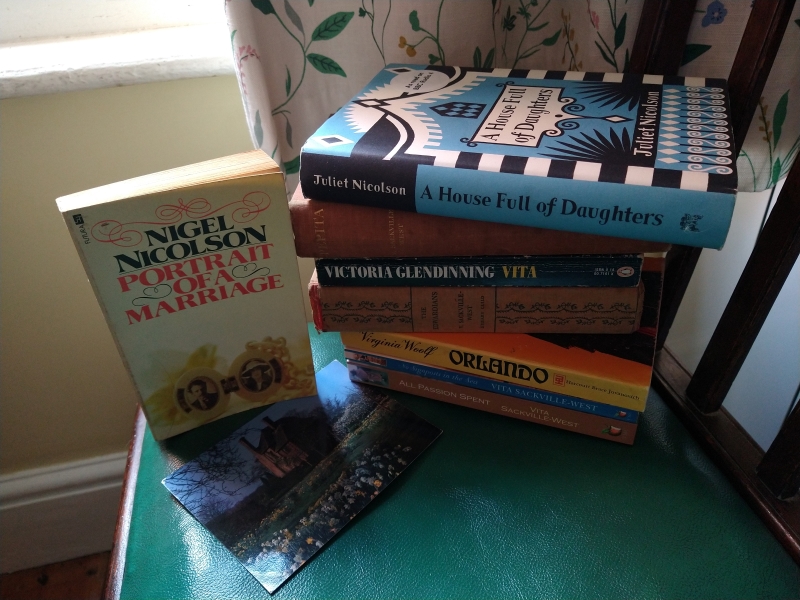

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters (Virago Anthology)

Books that dwell on family bonds often spotlight mothers and daughters, or fathers and sons; it seems a bit less common to examine the relationship with the parent of the opposite sex. In advance of Father’s Day, I picked up Fathers: Reflections by Daughters (1983; 1994) and read the first third. As I once did for Mother’s Day with another Virago anthology, Close Company: Stories of Mothers and Daughters, I’ll end up reading it across several years. Where that was a short fiction collection, though, this is all autobiographical pieces.

The section I’ve read so far contains seven essays counting editor Ursula Owen’s introduction, plus a retelling of the fairy tale “Cap o’ Rushes.” Most of the authors were born in the 1940s or 1950s, so a common element is having a father who served in the Second World War – or the First (for Angela Carter and Doris Lessing). There’s a sense, therefore, of momentous past experience that will never be disclosed. As Lessing writes of her father, “I knew him when his best years were over” – that is, after he had lost a leg, given up his favourite foods due to diabetes, and undertaken a doomed farming enterprise in colonial Africa.

Freudian interpretation seems like a given for several of the memoirists. Anne Boston was a posthumous child whose father was killed in the last days of WWII; in “Growing Up Fatherless,” she explores how this might have affected her.

I’ve always tended to discount the effects of being without a father – quite wrongly, I think now. There were effects, and they continued to influence my entire life, if anything increasingly so.

Among these effects, she enumerates a lack of proper “sexual conditioning.” Anthropologist Olivia Harris, too, wonders how a father determines a woman’s relationships with other men:

How far do women choose in their spouses, encourage in their sons, the ideal remembrance of the father? Am I, but not being married, refusing to exchange my father, or am I diffusing that chain of being?

Two authors specifically interrogate the alignment of the father with God. In “Heavenly Father,” Harris compares visions of fatherhood in various cultures, including in Anglican Christianity. Here the father, in parallel with the deity, is something of a distant moral arbiter. Sara Maitland felt the same about her father:

he really did correspond to the archetype of the Father. Many women grow out of their father when they discover that he is not really like what fathers are supposed, imaginatively, mythologically to be: he is weak, or a failure, or dishonest, or uninterested, or goes away. My father was not a perfect person, but he was very Father-like.

Unknown, aloof, a disciplinarian … I wonder if those descriptions resonate with you as much as they do with me?

In between pieces, Owen has reprinted 1–4 quotes from novels or academic sources that are relevant to fathers and daughters. The result is, as she acknowledges in the introduction, “a sort of collage.” She also remarks on the fact that it was difficult for more than one contributor to find a photo of herself with her father because “Dad always takes the photograph.” The essay I haven’t yet mentioned is a sweet but inconsequential two-pager by 13-year-old Kate Owen; it’s just occurred to me that that’s probably the editor’s daughter.

I’ll be interested to see how Michèle Roberts, Adrienne Rich, Alice Munro and more will clarify or complicate the picture of father–daughter relationships in the rest of the volume. (Secondhand from a National Trust bookshop)

#ReadingtheMeow2024 and 20 Books of Summer, 2: Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy

Reviews of books about cats have been a standard element on my blog over the years, and the second annual Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri, was a good excuse to pick up some more. Tomorrow I’ll review two cat-themed novels; today I have a 2002 memoir that I have been meaning to read for ages.

I discovered Piercy through her poetry, then read Woman on the Edge of Time, a feminist classic that contrasts utopian and dystopian views of the future. Like May Sarton (whom Piercy knew), she devotes equal energy to both fiction and poetry and is an inveterate cat lady. Piercy is still publishing and blogging at 88; I have much to catch up on from her back catalogue. A précis of her life is almost stranger than fiction: she grew up in poverty in Detroit, joining a teen gang and discovering her sexuality first with other girls (“The first time I had an orgasm—I was eleven—I was astonished and also I had a feeling of recognition. Of course, that’s it. As if that was what I had been expecting or looking for”) then with men; had a couple abortions, including one self-administered, then got sterilized; honed her writing craft at college; married three times – briefly to a Frenchman, an unhappy open arrangement, and now for 40+ years to fellow writer Ira Wood; and wrote like a dervish yet has remained on the periphery of the literary establishment and thus struggled financially.

Political activism has been a constant for Piercy, whether protesting the Vietnam War or supporting women’s reproductive rights. She and Wood also nurtured a progressive Jewish community around their Cape Cod home. Again like Sarton, she has always embraced the term feminist but been more resistant to queerness. A generational thing, perhaps; nowadays we would surely call Piercy bisexual or at least sexually fluid, but she’s more apt to dismiss her teen girlfriends and her later affairs with women as a phase. The personal life and career mesh here, though there is more of a focus on the former, such that I haven’t really gotten a clear idea of which of her novels I might want to try. Each chapter ends with one of her poems (wordy, autobiographical free verse), giving a flavour of her work in other genres. She portrays herself as a nomad who wandered various cities before settling into an unexpectedly homely and seasonal existence: “I am a stray cat who has finally found a good home.”

I admired Piercy’s self-knowledge here: her determination to write (including to keep her late mother alive in her) and to preserve the solitude necessary to her work –

I know I am an intense, rather angular passionate woman, not easy to like, not easy to live with, even for myself. Convictions, causes jostle in me. My appetites are large. I have learned to protect my work time and my privacy fiercely. I have been a better writer than a person, and again and again I made that choice. Writing is my core. I do not regret the security I have sacrificed to serve it.

and her conviction that motherhood was not for her –

I did not want children. I never felt I would be less of a woman, but I feared I would be less of a writer if I reproduced. I didn’t feel anything special about my genetic composition warranted replicating it. … I liked many of my friends’ children as they grew older: I was a good aunt. But I never desired to possess them or have one of my own. … I have never regretted staying childless. My privacy, my time for work … are precious. I feel my life is full enough.

“There were no role models for a woman like me,” she felt at the end of college, but she can in her turn be a role model of the female artist’s life, socially engaged and willing to take risks.

As to the title: There is, of course, special delight here for cat lovers. Piercy has had cats since she was a child, and in the Cape Cod era has usually kept a band of five or so. In the interludes we meet some true characters: Arofa the Siamese, Cho-Cho who lived to 21, mother and son Dinah and Oboe, alpha male Jim Beam, and many more. Of course, they age and fall ill and there are some goodbye scenes. She mostly describes these unsentimentally – if you’ve read Doris Lessing on cats, I’d say the attitude is similar. There are extremes of both love and despair: she licks a kitten to bond with her; she euthanizes one beloved cat herself. She wrote this memoir at 65 and felt that her cats were teaching her how to age.

There is a sadness to living with old cats; also a comfort and pleasure, for you know each other thoroughly and the trust is almost absolute. … The knowledge of how much I will miss them is always with me, but so is the sense of my own time flowing out, my life passing and the necessity to value it as I value them. Old cats are precious.

Even those unfamiliar with Piercy’s work might enjoy reading a perspective on the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s. This was right up my street because of her love of cats, her defence of the childfree life, and her interest in identity and memory. Because she doesn’t talk in depth about her oeuvre, you needn’t have read anything else of hers to appreciate reading this. I hope you have a cat who will nap on your lap as you do so. (Secondhand, a gift from my wish list) ![]()

Wendell Berry’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” & Why I Acquired My First Smartphone at Age 40.5

Wendell Berry is an American treasure: the 89-year-old Kentucky farmer is also a philosopher, poet, theologian, and writer of fiction, and many of his pronouncements bear the timeless wisdom of a biblical prophet. I’ve read his work from several genres and was curious to see how this 1987 essay – originally published in Harper’s Magazine and reprinted, along with some letters to the editor in response, plus extra commentary in the form of a 1990 essay, by Penguin in 2018 as the 50th and final entry in their Penguin Modern pamphlet series – might resonate with my own reluctance to adopt current technology.

The title essay is brief, barely filling 4.5 pages of a small-format paperback. It’s so concise that it would be difficult to summarize in many fewer words, but I’ll run through the points he makes across the initial essay, the replies to the correspondence, and a follow-up piece entitled “Feminism, the Body and the Machine” (1989). Berry laments his reliance on energy corporations and wants to limit that as much as possible. He decries consumerism in general; he isn’t going to acquire something just to be ‘keeping up with the times’. He doesn’t believe a computer will make his work better, and it doesn’t meet his criteria for a useful tool (smaller, cheaper and less energy-intensive than what it replaces; sourced locally and easily repaired by a non-specialist). He is perfectly happy with his current arrangement: he writes his work by hand and his wife types it up for him. He is loath to lose this human touch.

The letters to the editor, predictably, accuse him of self-righteousness for depicting his choice as the more virtuous one. The correspondents also felt they had to stand up for Berry’s wife, who might have better things to do than act as her husband’s secretary. This is the only time the author becomes slightly defensive, basically saying, ‘you don’t know anything about me, my wife or my marriage … maybe she wants to!’ He doubles down on the environmental harm caused by technology and consumerism, acknowledging his continued dependence on fossil fuels and vowing to avoid them, and unnecessary purchases, where possible.

If some technology does damage to the world, … then why is it not reasonable, and indeed moral, to try to limit one’s use of that technology?

To the extent that we consume, in our present circumstances, we are guilty. To the extent that we guilty consumers are conservationists, we are absurd. … can we do something directly to solve our share of the problem? … Why then is not my first duty to reduce, so far as I can, my own consumption?

If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer one is not to use one.

He even appears to speak prophetically to the rise of artificial intelligence:

My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. … And in our time this means that we must save ourselves from the products that we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves. The danger most immediately to be feared in ‘technological progress’ is the degradation and obsolescence of the body.

Certain of his arguments felt relevant to me as I ponder my own relationship to technology. I compose all my reviews on a 19-year-old personal computer that’s not connected to the Internet. I don’t listen to the radio and have seen maybe three films in the past two years. We’ve been television-free for a decade and I have never regretted it (Berry: “It is easy – it is even a luxury – to deny oneself the use of a television set, and I zealously practice that form of self-denial. Every time I see television (at other people’s houses), I am more inclined to congratulate myself on my deprivation.”).

I find it so hard to adjust to new tech that my reluctance may have shaded into suspicion. I’m certainly no early adopter, but I’d also object to the label “Luddite”: since 2013 I’ve been using e-readers, which are invaluable in my reviewing work. But for 15 years or more I have been looking at other people and their smartphones with disdain. I prided myself on my resistance. Stubbornness seemed like a virtue when the alternative was spending a lot of money on something I didn’t need.

Receiving my first cell phone in July 2004 (with my dad at left; at Dulles airport).

Two months ago, though, I finally gave in and accepted a hand-me-down Motorola Android phone from my father-in-law, after nearly 20 years of using an old-style mobile phone. As we were renegotiating our phone and Internet contract, I got virtually unlimited minutes and data on this device for £6/month, with no initial outlay. Had I been forced to make a purchase, I think I would still be holding out. But I had gotten to the point where refusal was cutting off my nose to spite my face. Why keep martyring myself – saying I couldn’t make important household phone calls because they drained my pay-as-you-go credit; learning complex workarounds to post to Instagram from my PC; taking crap photos on a digital camera held together with a rubber band? Why resist utility just for the sake of it?

To be clear, this was not a matter of saving time. I’m not a busy person. Plus I believe there is value in slowing down and acting deliberately. (See this book-based article I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018 on the benefits of “wasting time.”) Mindless scrolling is as much a temptation on a PC as on a phone, so avoiding social media was not a motive for me; others with addictive tendencies may decide otherwise. Nor did I view convenience as reason enough per se. However, I admit I was attracted to the efficiency of a pocket-sized device that can at once replace a computer, pager, telephone, Rolodex, phonebook, camera, photo album, television screen, music player, camcorder, Dictaphone, stopwatch, calculator, map, satnav, flashlight, encyclopaedia, Kindle library, calendar, diary, Post-It notes, notebook, alarm clock and mirror. (Have I missed anything?) Talk about multi-tasking!

Out with the old, in with the new?

I would still say that I object to tech serving as a status symbol or a basis for self-importance, and I’d be pretty dubious about it ever being a worthwhile hobby. Should this phone fail me in future, I’ll copy my husband’s habit of buying a secondhand handset for £60–80. I wouldn’t acquire something that represented new extraction of rare resources. Treating things (or people) as disposable is anathema to me, something about which I know Berry would agree. I’m naturally parsimonious, obsessive about keeping things going for as long as possible and recycling them responsibly when they reach their end of life.

It’s one reason why I’ve gotten involved in the Repair Café movement. I volunteer for our local branch, which started up in February, on the admin and publicity side of things. The old-fashioned, make-do-and-mend ethos appeals to me. It’s the same spirit evoked in the lyrics of American singer-songwriter Mark Erelli’s “Analog Hero”:

He’s the fix-it man, the fix-it man

If he can’t put it back together, then it was never worth a damn

Maybe he’s crazy for trying to save what’s already gone

Now it ain’t even broken and we’re going for the upgrade

Nobody thinks twice ’bout what we’re really throwing away

It’s out with the old, in with the new…

I can imagine Wendell Berry still pecking out his words on a typewriter on his Kentucky farm. He’s an analogue hero, too. And he doesn’t go nearly as far as Mark Boyle, whose radical life experiment is recounted in The Way Home: Tales from a life without technology, which I reviewed for Shiny New Books in 2019.

I have pretty much made my peace with owning a smartphone. I have few apps and am still more likely to work at my PC or on paper. I’ll concede that I enjoy being able to post to X or Instagram wherever I am, and to keep up with messages on the go. (I used to have to say cryptic things to friends like, “once I leave the house, I will be unavailable except by text.”) Mostly, I’m relieved to have shed the frustrations of outmoded tech. Though I still keep my Nokia brick by my bedside as a trusty alarm clock – and a torch for when the cat wakes me between 2 and 5 each morning.

Ultimately, I feel, a smartphone is a tool like any other. It’s how you use it. Salman Rushdie comes to much the same conclusion about the would-be murder weapon wielded against him: “a knife is a tool, and acquires meaning from the use we make of it. It is morally neutral” (from Knife).

Berry’s argument about overreliance on energy remains a good one, but we are all so complicit in so many ways – even more so than in the late 1980s when he was writing – that avoiding the computer, and now the smartphone, doesn’t seem to hold particular merit. While this pamphlet will be but a quaint curio piece for most readers (rather than a parallel to the battle of wills I’ve conducted with myself), it is engaging and convincing, and the societal issues it considers are still ones to be wrestled with.

My copy was purchased with part of a £30 voucher I received free from Penguin UK for being part of their “Bookmarks” online community – answering polls, surveys, etc.

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez: This debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming, tornadoes and cicadas. But her Kansas isn’t all rose-tinted nostalgia; there’s an edge of sadness and danger. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. She also takes inspiration from headlines. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for. (Full review to come.)

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez: This debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming, tornadoes and cicadas. But her Kansas isn’t all rose-tinted nostalgia; there’s an edge of sadness and danger. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. She also takes inspiration from headlines. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for. (Full review to come.)

Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.”

Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.” Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.

Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)  Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as

Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as  Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)