Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

#1925Club: The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov

Simon and Kaggsy’s classics reading weeks always get me picking up older books. I found this unusual Russian novella on a giveaway pile a few years ago and it’s been on my #NovNov possibility shelf ever since, but now turned out to be the perfect time for it. This review also fits into the Hundred Years Hence challenge.

Sharik is an abused stray dog, living on scraps on the snowy streets of Moscow until Professor Philip Philipovich Preobrazhensky takes him in. The professor is a surgeon renowned for his rejuvenation procedures – implanting monkey ovaries into a middle-aged lady, for instance – and he has designs on the mutt. His new strategy is to take the pituitary gland and testicles of a just-deceased young man and transplant them into Sharik. The central chapter is composed of medical notes taken by Preobrazhensky’s assistant, Dr. Bormenthal. Gradually, a transformation is achieved: The dog’s bark becomes more of a human groan and his fur and tail fall off. Soon the new man is fully convincing: eating, dressing and conversing. Even in a matter-of-fact style, the doctor’s clinical observations are hilarious. “The dog[,] in the presence of Zina and myself, had called Prof. Preobrazhensky a ‘bloody bastard’. … Heard to ask for ‘another one, and make it a double.’” The scientists belatedly look into the history of the man whose glands they harvested and discover to their horror that he was an alcoholic petty thief who died in a bar fight. Sharikov follows suit as an inebriated boor who pesters women, wants to be known as Poligraph Poligraphovich – and still chases cats. Is it too late to reverse a Frankenstein-esque trial gone wrong?

This was a fairly entertaining fable-like story, with whimsical fragments of narration from Sharik himself at the start and close. The blurb inside the jacket of my 1968 Harvill Press hardback suggests “The Heart of a Dog can be enjoyed solely as a comic story of splendid absurdity; it can also be read as a fierce parable about the Russian Revolution.” The allegorical meaning could easily have passed me by, being less overt than in Animal Farm. Reading a tiny bit of external information, I see that this has been interpreted as a satire on the nouveau riche during the Bolshevik era: Sharikov complains about how wealthy the professor is and proposes that he sacrifice some of his apartment-cum-office’s many rooms to others who have nowhere to live. But yes, I mostly stayed at the surface level and found an amusing mad-scientist cautionary tale. I’ll read more by Bulgakov – I’ve had a copy of The Master and Margarita for ages. Next year’s Reading the Meow week might be my excuse.

This was a fairly entertaining fable-like story, with whimsical fragments of narration from Sharik himself at the start and close. The blurb inside the jacket of my 1968 Harvill Press hardback suggests “The Heart of a Dog can be enjoyed solely as a comic story of splendid absurdity; it can also be read as a fierce parable about the Russian Revolution.” The allegorical meaning could easily have passed me by, being less overt than in Animal Farm. Reading a tiny bit of external information, I see that this has been interpreted as a satire on the nouveau riche during the Bolshevik era: Sharikov complains about how wealthy the professor is and proposes that he sacrifice some of his apartment-cum-office’s many rooms to others who have nowhere to live. But yes, I mostly stayed at the surface level and found an amusing mad-scientist cautionary tale. I’ll read more by Bulgakov – I’ve had a copy of The Master and Margarita for ages. Next year’s Reading the Meow week might be my excuse.

[Translated from Russian by Michael Glenny, 1968]

(Free from a neighbour, formerly part of Scarborough Public Library stock) ![]()

I also intended to read An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser from the university library, having a dim memory of a black-and-white film version starring Montgomery Clift (A Place in the Sun). But the catalogue’s promised 400-some pages was a lie; there are two volumes in one, totaling 840 pages. So that was a nonstarter.

But here are some other famous 1925 titles that I’ve read (I’m now at 7 out of the top 15 on the Goodreads list of the most popular books published in 1925):

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Trial by Franz Kafka

The Painted Veil by W. Somerset Maugham

Emily Climbs by L.M. Montgomery

Carry On, Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, 1970 Club, and 1952 Club.

Nine Days in Germany and What I Read, Part I: Berlin

We’ve actually been back for more than a week, but soon after our return I was felled by a nasty cold (not Covid, surprisingly), which has left me with a lingering cough and ongoing fatigue. Finally, I’m recovered just about enough to report back.

This Interrail adventure was more low-key than the one we took in 2016. The first day saw us traveling as far as Aachen, just over the border from France. It’s a nice small city with Christian and culinary history: Charlemagne is buried in the cathedral; and it’s famous for a chewy, spicy gingerbread called printen. Before our night in a chain hotel, we stumbled upon the mayor’s Green Party rally in the square – there was to be an election the following day – and drank and dined well. The Gin Library, spotted at random on the map, is an excellent and affordable Asian-fusion cocktail bar. My “Big Ben,” for instance, featured Tanqueray gin, lemon juice, honey, fresh coriander, and cinnamon syrup. Then at Hanswurst – Das Wurstrestaurant (cue jokes about finding the “worst” restaurant in Aachen!), a superior fast-food joint, I had the vegetarian “Hans Berlin,” a scrumptious currywurst with potato wedges.

The next day it was off to Berlin with a big bag of bakery provisions. For the first time, we experienced the rail cancellations and delays that would plague us for much of the next week. We then had to brave the only supermarket open in Berlin on a Sunday – the Rewe in the Hauptbahnhof – before taking the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz, the nearest station to our Airbnb flat.

It was all worth it to befriend Lemmy (the ginger one) and Roxanne. It’s a sweet deal the host has here: whenever she goes away, people pay her to look after her cats. At the same time as we were paying for a cat-sitter back home. We must be chumps!

I’ll narrate the rest of the trip through the books I read. I relished choosing relevant reads from my shelves and the library’s holdings – I was truly spoiled for choice for Berlin settings! – and I appreciated encountering them all on location.

As soon as we walked into the large airy living room of the fifth-floor Airbnb flat, I nearly laughed out loud, for there in the corner was a monstera plant. The trendy, minimalist décor, too, was just like that of the main characters’ place in…

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes]

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss)

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

- Reichstag (Photos 1, 2 and 4 by Chris Foster)

- Reichstag tower designed by Norman Foster

- The Philharmonic

- Brandenburg Gate (Photos 1-3 by Chris Foster)

- Postdam’s Park Sanssouci

- Wen Cheng noodles

- Brammibal’s vegan doughnuts

I brought along another novella that proved an apt companion for our explorations of the city. Even just spotting familiar street and stop names in it felt like reassurance.

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri (2022)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library) ![]()

We spent a drizzly and slightly melancholy first day and final morning making pilgrimages to Jewish graveyards and monuments to atrocities, some of them nearly forgotten. I got the sense of a city that has been forced into a painful reckoning with its past – not once but multiple times, perhaps after decades of repression. One morning we visited the claustrophobic monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and, in the Tiergarten, the small memorials to the Roma and homosexual victims of the Holocaust. The Nazis came for political dissidents and the disabled, too, as I was reminded at the Topography of Terrors, a free museum where brutal facts are laid bare. We didn’t find the courage to go in as the timeline outside was confronting enough. I spotted links to the two historical works I was reading during my stay (Stella the red-haired Jew-catcher in the former and Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute in the latter). As I read both, I couldn’t help but think about the current return of fascism worldwide and the gradual erosion of rights that should concern us all.

Aimée and Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fischer (1994; 1995)

[Translated from German by Edna McCown]

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Milena and Margarete: A Love Story in Ravensbrück by Gwen Strauss]

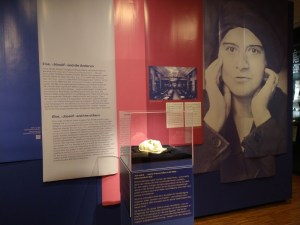

The Lilac People by Milo Todd (2025)

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss)

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Under the Pink Triangle by Katie Moore (set in Dachau)]

We might have been at the Eldorado in the early 1930s on the evening when we ventured out to the bar Zosch for a “New Orleans jazz” evening. The music was superb, the German wine tasty, the whole experience unforgettable … but it sure did feel like being in a bygone era. We’re so used to the indoor smoking ban (in force in the UK since 2007) that we didn’t expect to find young people chain-smoking rollies in an enclosed brick basement, and got back to the flat with our clothes reeking and our lungs burning.

It was good to see visible signs of LGTBQ support in Berlin, though they weren’t as prevalent as I perhaps expected.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

Other Berlin highlights: a delicious vegetarian lunch at the canteen of an architecture firm, the Ritter chocolate shop, and the pigeons nesting on the flat balcony – the chicks hatched on our final morning!

And a belated contribution to Short Story September:

Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue (2006)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Trip write-up to be continued (tomorrow, with any luck)…

I died and went

I died and went I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this.

I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this. I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing.

I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing. Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away.

Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away.

This was among my

This was among my  All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!) This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues. I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (

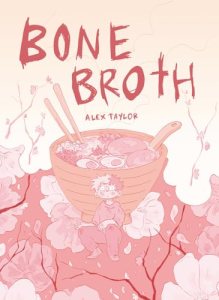

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults ( Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

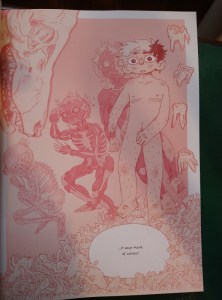

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it. This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of  I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s

I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s  Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to

Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to  The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after

The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after  A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

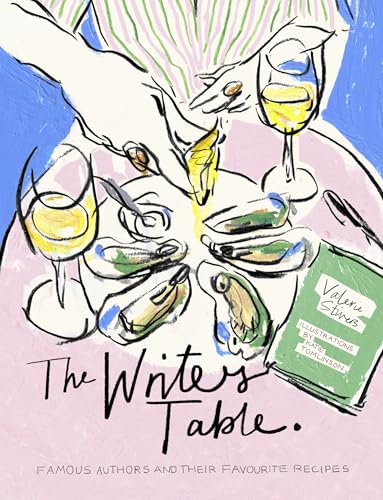

A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)  Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Stats: 12 stories (6 x 1st-person, 6 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 12 stories (6 x 1st-person, 6 x 3rd-person) Stats: 11 stories (3 x 2nd-person, 8 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 11 stories (3 x 2nd-person, 8 x 3rd-person) Stats: 16 stories (12 x 1st-person, 1 x 1st-person plural, 1 x 2nd-person, 2 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 16 stories (12 x 1st-person, 1 x 1st-person plural, 1 x 2nd-person, 2 x 3rd-person) Stats: 50 stories, a mixture of 1st- and 3rd-person

Stats: 50 stories, a mixture of 1st- and 3rd-person Stats: 11 stories, mostly by Memorial University creative writing graduates (7 x 1st-person, 1 x 2nd-person, 3 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 11 stories, mostly by Memorial University creative writing graduates (7 x 1st-person, 1 x 2nd-person, 3 x 3rd-person) Stats: 6 stories (5 x 1st-person, 1 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 6 stories (5 x 1st-person, 1 x 3rd-person) Stats: 14 stories (plus a handful of poems and an autobiographical fragment), all 1st-person

Stats: 14 stories (plus a handful of poems and an autobiographical fragment), all 1st-person Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

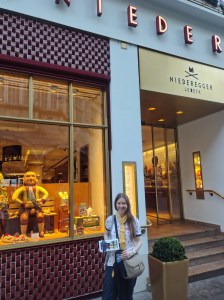

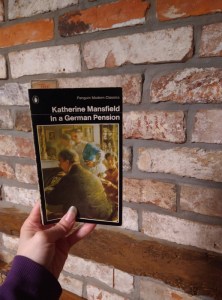

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

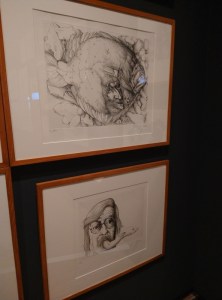

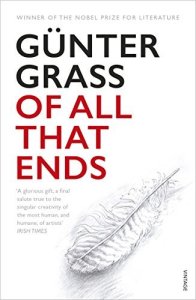

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)