Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

Literary Wives Club: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (2021)

Swedish author Elin Cullhed won the August Prize and was a finalist for the Strega European Prize with this first novel for adults. Euphoria is a recreation of Sylvia Plath’s state of mind in the last year of her life. It opens on 7 December 1962 in Devon with a list headed “7 REASONS NOT TO DIE,” most of which centre on her children, Frieda and Nick. She enumerates the pleasures of being in a physical body and enjoying coastal scenery. But she also doesn’t want to give her husband, poet Ted Hughes, the satisfaction of having his prophecies about her mental illness come true.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Cullhed seems to hew to biographical detail, though I’m not particularly familiar with the Hughes–Plath marriage. Scenes of their interactions with neighbours, Plath’s mother, and Ted’s lover Assia Wevill make their dynamic clear. The prose grows more nonstandard; run-on sentences and all-caps phrases indicate increasing mania. There are also lovely passages that seem apt for a poet: “Ted’s crystalline sly little mint lozenge eyes. Narrow foxish. Thin hard. His eyes, so embittered.” The use of language is effective at revealing Plath’s maternal ambivalence and shaky mental health. Somehow, though, I found this quite tedious by the end. Not among my favourite biographical novels, but surely a must-read for Plath fans. ![]()

Translated from the Swedish by Jennifer Hayashida in 2022 – our first read in translation, I think? And what a brilliant cover.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Marriage is claustrophobic here, as in so many of the books we read. Much as she loves her children, Plath finds the whole wifehood–motherhood complex to be oppressive and in direct conflict with her ambitions as an author. Sharing a vocation with her husband, far from helping him understand her, only makes her more bitter that he gets the time and exposure she so longs for. More than 60 years later, Plath’s death still echoes, a tragic loss to literature.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in March: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus – I’ve read this before but will plan to skim back through a copy from the library.

Nonfiction November: Two Memoirs of Biblical Living by Evans and Jacobs

I love a good year-challenge narrative and couldn’t resist considering these together because of the shared theme. Sure, there’s something gimmicky about a rigorously documented attempt to obey the Bible’s literal commandments as closely as possible in the modern day. But these memoirs arise from sincere motives, take cultural and theological matters seriously, and are a lot of fun to read.

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs (2007)

Jacobs came up with the idea, so I’ll start with him. His first book, The Know-It-All, was about absorbing as much knowledge as possible by reading the encyclopaedia. This starts in similarly intellectual fashion with a giant stack of Bible translations and commentaries. From one September to the next, Jacobs vows, he’ll do his best to understand and implement commandments from both the Old and New Testaments. It’s not a completely random choice of project in that he’s a secular Jew (“I’m Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”). Firstly, and most obviously, he stops shaving and getting haircuts. “As I write this, I have a beard that makes me resemble Moses. Or Abe Lincoln. Or [Unabomber] Ted Kaczynski. I’ve been called all three.” When he also takes to wearing all white, he really stands out on the New York subway system. Loving one’s neighbour isn’t easy in such an antisocial city, but he decides to try his best.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

The book is a near-daily journal, with a new rule or three grappled with each day. There are hundreds of strange and culturally specific guidelines, but the heart issues – covetousness, lust – pose more of a challenge. Alongside his work as a journalist for Esquire and this project, Jacobs has family stuff going on: IVF results in his wife’s pregnancy with twin boys. Before they become a family of five, he manages to meet some Amish people, visit the Creation Museum, take a trip to the Holy Land to see a long-lost uncle, and engage in conversation with Evangelicals across the political spectrum, from Jerry Falwell’s megachurch to Tony Campolo (who died just last week). Jacobs ends up a “reverent agnostic.” We needn’t go to such extremes to develop the gratitude he feels by the end, but it sure is a hoot to watch him. This has just the sort of amusing, breezy yet substantial writing that should engage readers of Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Jon Ronson. (Free mall bookshop) ![]()

A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master” by Rachel Held Evans (2012)

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

It’s a sweet, self-deprecating book. You can definitely tell that she was only 29 at the time she started her project. It’s okay with me that Evans turned all her literal intentions into more metaphorical applications by the end of the year. She concludes that the Church has misused Proverbs 31: “We abandoned the meaning of the poem by focusing on the specifics, and it became just another impossible standard by which to measure our failures. We turned an anthem into an assignment, a poem into a job description.” Her determination is not to obsess over rules but to continue with the habits that benefited her spiritual life, and to champion women whenever she can. I suspect this is a lesser entry from Evans’s oeuvre. She died too soon – suddenly in 2019, of brain swelling after a severe allergic reaction to an antibiotic – but remains a valued voice, and I’ll catch up on the rest of her books. Searching for Sunday, for instance, was great, and I’m keen to read Evolving in Monkey Town (about living in Dayton, Tennessee, where the famous Scopes Monkey Trial took place). (Birthday gift from my wish list, 2023) ![]()

#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

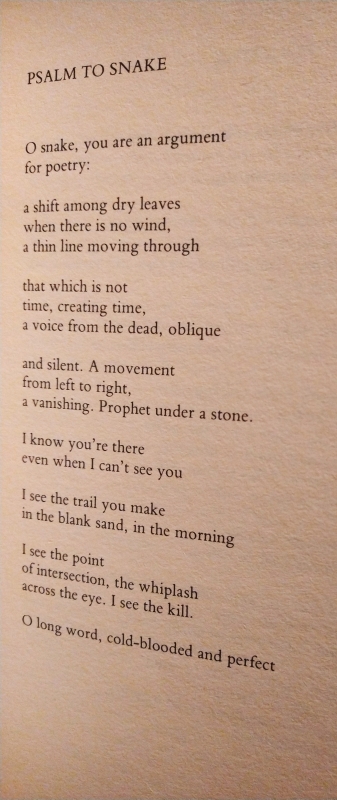

Interlunar (1984)

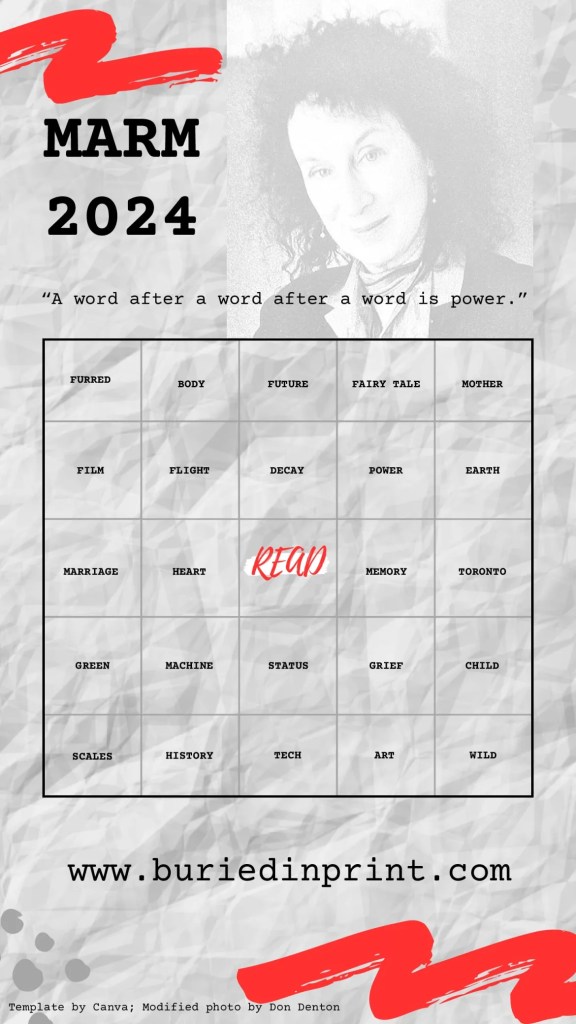

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full  In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness)

In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness) Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full

Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full  Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full

Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full  Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read  I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]  “They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]  I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]  {BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]  The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse.

The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse. The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted.

The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted. Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour.

Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour. My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men.

My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men. Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]

Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]  Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]

Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]  X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]