Book Serendipity, Mid-February to Mid-April

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

Last time, my biggest set of coincidences was around books set in or about Korea or by Korean authors; this time it was Ghana and Ghanaian authors:

- Reading two books set in Ghana at the same time: Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor and His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie. I had also read a third book set in Ghana, What Napoleon Could Not Do by DK Nnuro, early in the year and then found its title phrase (i.e., “you have done what Napoleon could not do,” an expression of praise) quoted in the Medie! It must be a popular saying there.

- Reading two books by young Ghanaian British authors at the same time: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley and Maame by Jessica George.

And the rest:

- An overweight male character with gout in Where the God of Love Hangs Out by Amy Bloom and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho by Paterson Joseph.

- I’d never heard of “shoegaze music” before I saw it in Michelle Zauner’s bio at the back of Crying in H Mart, but then I also saw it mentioned in Pulling the Chariot of the Sun by Shane McCrae.

- Sheila Heti’s writing on motherhood is quoted in Without Children by Peggy O’Donnell Heffington and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata. Before long I got back into her novel Pure Colour. A quote from another of her books (How Should a Person Be?) is one of the epigraphs to Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home.

- Reading two Mexican books about motherhood at the same time: Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata.

- Two coming-of-age novels set on the cusp of war in 1939: The Inner Circle by T.C. Boyle and Martha Quest by Doris Lessing.

- A scene of looking at peculiar human behaviour and imagining how David Attenborough would narrate it in a documentary in Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson and I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai.

- The painter Caravaggio is mentioned in a novel (The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent) plus two poetry books (The Fourth Sister by Laura Scott and Manorism by Yomi Sode) I was reading at the same time.

- Characters are plagued by mosquitoes in The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

- Edinburgh’s history of grave robbing is mentioned in The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent and Womb by Leah Hazard.

- I read a chapter about mayflies in Lev Parikian’s book Taking Flight and then a poem about mayflies later the same day in Ephemeron by Fiona Benson.

- Childhood reminiscences about playing the board game Operation and wetting the bed appear in Homesick by Jennifer Croft and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

- Fiddler on the Roof songs are mentioned in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman.

- There’s a minor character named Frith in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

- Scenes of a female couple snogging in a bar bathroom in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and The Garnett Girls by Georgina Moore.

- The main character regrets not spending more time with her father before his sudden death in Maame by Jessica George and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti.

- The main character is called Mira in Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti, and a Mira is briefly mentioned in one of the stories in Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans.

- Macbeth references in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – my second Macbeth-sourced title in recent times, after Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin last year.

- A ‘Goldilocks scenario’ is referred to in Womb by Leah Hazard (the ideal contraction strength) and Taking Flight by Lev Parikian (the ideal body weight for a bird).

- Caribbean patois and mention of an ackee tree in the short story collection If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery and the poetry collection Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa.

- The Japanese folktale “The Boy Who Drew Cats” appeared in Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng, which I read last year, and then also in Enchantment by Katherine May.

- Chinese characters are mentioned to have taken part in the Tiananmen Square massacre/June 4th incident in Dear Chrysanthemums by Fiona Sze-Lorrain and Oh My Mother! by Connie Wang.

- Endometriosis comes up in What My Bones Know by Stephanie Foo and Womb by Leah Hazard.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Blog Tour Review: Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane

Ask Again, Yes is about the inextricable links that form between two Irish-American policemen’s families in New York. Francis Gleeson and Brian Stanhope meet as cops on the same South Bronx beat in July 1973 and soon move upstate, settling in as close neighbors in the suburb of Gillam. After a stillbirth and a miscarriage, Brian and his wife Anne, who’s from Dublin, finally have a son, Peter. Six months later, Francis and Lena’s third daughter, Kate, is born; from the start it’s as if Peter and Kate are destined for each other. They’re childhood best friends, but then, like Romeo and Juliet, have to skirt around the animosity that grows between their families to be together as adults.

Anne’s mental health issues and the Stanhope family history of alcoholism will lead to explosive situations that require heroic acts of forgiveness. I ached for many characters in turn, especially Lena and Kate. The title sets up a hypothetical question: if you had your life to live again, knowing what the future held, would you have it the same way? Keane suggests that for her characters the answer would be yes, even if they knew about all the bad that was to come alongside the good. Impossible to write any more about the plot without giving too much away, so suffice it to say that this is a wrenching story of the ways in which we repeat our family’s mistakes or find the grace to move on and change for the better.

As strong as the novel’s characterization is, and as intricately as the storyline is constructed around vivid scenes, I found this a challenging read and had to force myself to pick it up for 20 pages a day to finish it in time for my blog tour slot. Simply put, it is relentless. And I say that even though I was reading a novel about a school shooting at the same time. There aren’t many light moments to temper the sadness. (Also, one of my pet peeves in fiction is here: skipping over 15 years within a handful of pages.) Still, I expect Keane’s writing will appeal to fans of Celeste Ng and Ann Patchett – the latter’s Commonwealth, in particular, came to mind right away.

My rating:

Ask Again, Yes was published by Michael Joseph (Penguin) on August 8th. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

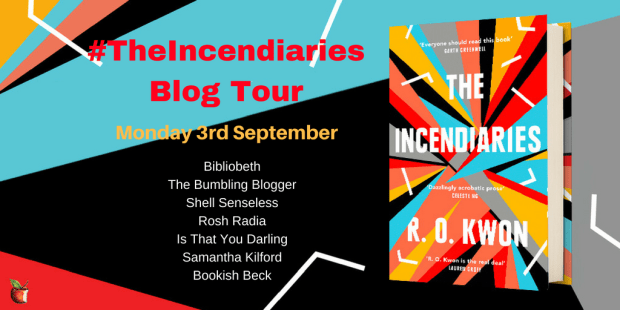

Blog Tour Review: The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

Much of the book is filtered through Will’s perspective; even sections headed “Phoebe” and “John Leal” most often contain his second-hand recounting of Phoebe’s words, or his imagined rendering of Leal’s thoughts – bizarre and fervent. Only in a few spots is it clear that the “I” speaking is actually Phoebe. This plus a lack of speech marks makes for a somewhat disorienting reading experience, but that is very much the point. Will and Phoebe’s voices and personalities start to merge until you have to shake your head for some clarity. The irony that emerges is that Phoebe is taking the opposite route to Will’s: she is drifting from faithless apathy into radical religion, drawn in by Jejah’s promise of atonement.

As in Celeste Ng’s novels, we know from the very start the climactic event that powers the whole book: the members of Jejah set off a series of bombs at abortion clinics, killing five. The mystery, then, is not so much what happened but why. In particular, we’re left to question how Phoebe could be transformed so quickly from a vapid party girl to a religious extremist willing to suffer for her beliefs.

Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word. I can see how some might find the style frustratingly oblique, but for me it was razor sharp, and the compelling religious theme was right up my street. It’s a troubling book, one that keeps tugging at your elbow. Recommended to readers of Sweetbitter and Shelter.

Favorite lines:

“This has been the cardinal fiction of my life, its ruling principle: if I work hard enough, I’ll get what I want.”

“People with no experience of God tend to think that leaving the faith would be a liberation, a flight from guilt, rules, but what I couldn’t forget was the joy I’d known, loving Him.”

My rating:

The Incendiaries will be published by Virago Press on September 6th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Note: An excerpt from The Incendiaries appeared in The Best Small Fictions 2016 (ed. Stuart Dybek), which I reviewed for Small Press Book Review. I was interested to look back and see that, at that point, her work in progress was entitled Heroics.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews are appearing today.

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit. A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one.

A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one. Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his.

Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his. Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling.

Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling. Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement. Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.

Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant. Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?

Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!).

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room.

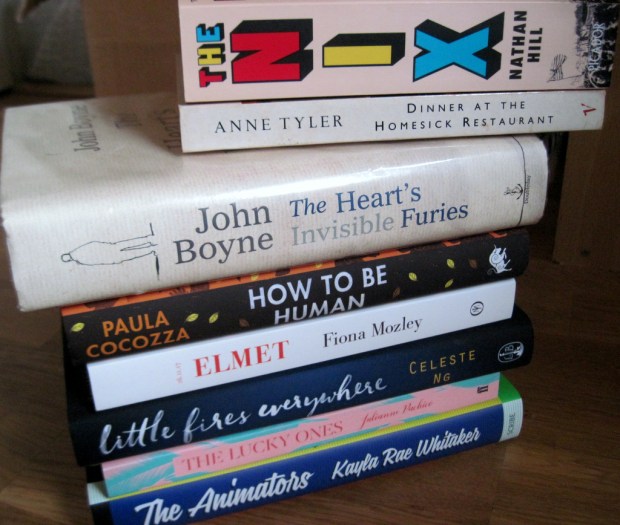

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food. Human Acts, Han Kang: I admit, this book, which traces the human costs of the brutally repressed Gwanju Uprising, is difficult to read. Worth the effort, though, for its urgent questions about the nature of humanity.

Human Acts, Han Kang: I admit, this book, which traces the human costs of the brutally repressed Gwanju Uprising, is difficult to read. Worth the effort, though, for its urgent questions about the nature of humanity. Pachinko, Min Jin Lee: A twentieth-century family saga about Korean immigrants in Japan. Expansive and richly textured.

Pachinko, Min Jin Lee: A twentieth-century family saga about Korean immigrants in Japan. Expansive and richly textured. The Essex Serpent, Sarah Perry: A recently widowed natural historian and a village curate spar over rumors of a returned prehistoric serpent. Sumptuous.

The Essex Serpent, Sarah Perry: A recently widowed natural historian and a village curate spar over rumors of a returned prehistoric serpent. Sumptuous. Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders: The resident ghosts look on with consternation as Abraham Lincoln visits their cemetery to mourn over the body of his son, Willie. Polyphonic; extraordinarily moving.

Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders: The resident ghosts look on with consternation as Abraham Lincoln visits their cemetery to mourn over the body of his son, Willie. Polyphonic; extraordinarily moving. The Wanderers, Meg Howrey: Three astronauts undertake a long-term simulation of a mission to Mars, leaving their loved ones behind. Wonderful literary sci-fi, absorbing in its physical and psychological detail.

The Wanderers, Meg Howrey: Three astronauts undertake a long-term simulation of a mission to Mars, leaving their loved ones behind. Wonderful literary sci-fi, absorbing in its physical and psychological detail. Exit West, Mohsin Hamid: Two young lovers become part of a global migration through mysterious doors that connect locations all over the world. Intimate and tender.

Exit West, Mohsin Hamid: Two young lovers become part of a global migration through mysterious doors that connect locations all over the world. Intimate and tender. My Darling Detective, Howard Norman: A tale of family secrets set in 1970s Halifax, featuring plainspoken people and delightful use of radio drama. From my review: “noir with a spring in its step and a lilt in its voice.”

My Darling Detective, Howard Norman: A tale of family secrets set in 1970s Halifax, featuring plainspoken people and delightful use of radio drama. From my review: “noir with a spring in its step and a lilt in its voice.” The Mountain, Paul Yoon: Six exquisite short stories, set in different locations over the past 100 years, from a master of the form.

The Mountain, Paul Yoon: Six exquisite short stories, set in different locations over the past 100 years, from a master of the form. The Stone Sky, N. K. Jemisin: The blistering final book in Ms. Jemisin’s stunning Broken Earth trilogy (must be read in order, so start with The Fifth Season if you’re new to the series). Superb speculative fiction.

The Stone Sky, N. K. Jemisin: The blistering final book in Ms. Jemisin’s stunning Broken Earth trilogy (must be read in order, so start with The Fifth Season if you’re new to the series). Superb speculative fiction. Little Fires Everywhere, Celeste Ng: The complexities of race, class, and motherhood swirl in a Cleveland suburb (my hometown) in this deft, compassionate novel.

Little Fires Everywhere, Celeste Ng: The complexities of race, class, and motherhood swirl in a Cleveland suburb (my hometown) in this deft, compassionate novel. Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado: Short stories grounded in the body but shot through with elements of horror and fantasy. Won’t take it easy on you, but you won’t want to stop reading, either. Brilliant.

Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado: Short stories grounded in the body but shot through with elements of horror and fantasy. Won’t take it easy on you, but you won’t want to stop reading, either. Brilliant. The Power, Naomi Alderman: Women harness a power within themselves that turns the tables on men. Atwoodian dystopia at its finest.

The Power, Naomi Alderman: Women harness a power within themselves that turns the tables on men. Atwoodian dystopia at its finest.