Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

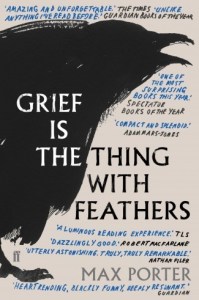

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

Three in Translation for #NovNov23: Baek, de Beauvoir, Naspini

I’m kicking off Week 3 of Novellas in November, which we’ve dubbed “Broadening My Horizons.” You can interpret that however you like, but Cathy and I have suggested that you might like to review some works in translation and/or think about any new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas. Literature in translation is still at the edge of my comfort zone, so it’s good to have excuses such as this (and Women in Translation Month each August) to pick up books originally published in another language. Later in the week I’ll have a contribution or two for German Lit Month too.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee (2018; 2022)

[Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur]

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

There are bits of context and reflection, but I didn’t get a clear overall sense of the author as a person, just as a bundle of neuroses. Her psychiatrist tells her “writing can be a way of regarding yourself three-dimensionally,” which explains why I’ve started journaling – that, and I want believe that the everyday matters, and that it’s important to memorialize.

I think the book could have ended with Chapter 14, the note from her psychiatrist, instead of continuing with another 30+ pages of vague self-help chat. This is such an unlikely bestseller (to the extent that a sequel was published, by the same title, just with “Still” inserted!); I have to wonder if some of its charm simply did not translate. (Public library) [194 pages]

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir (2020; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Lauren Elkin]

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Whereas Sylvie loses her Catholic faith (“at one time, I had loved both Andrée and God with ferocity”), Andrée remains devout. She seems destined to follow her older sister, Malou, into a safe marriage, but before that has a couple of unsanctioned romances with her cousin, Bernard, and with Pascal (based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty). Sylvie observes these with a sort of detached jealousy. I expected her obsessive love for Andrée to turn sexual, as in Emma Donoghue’s Learned by Heart, but it appears that it did not, in life or in fiction. In fact, Elkin reveals in a translator’s note that the girls always said “vous” to each other, rather than the more familiar form of you, “tu.” How odd that such stiffness lingered between them.

This feels fragmentary, unfinished. De Beauvoir wrote about Zaza several times, including in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, but this was her fullest tribute. Its length, I suppose, is a fitting testament to a friendship cut short. (Passed on by Laura – thank you!) [137 pages]

(Introduction by Deborah Levy; afterword by Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, de Beavoir’s adopted daughter. North American title: Inseparable.)

Tell Me About It by Sacha Naspini (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford]

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The text is saturated with dialogue; quick wits and sharp tempers blaze. You could imagine this as a radio or stage play. The two characters discuss their children and the town’s scandals, including a lothario turned artist’s muse and a young woman who died by suicide. “The past is full of ghosts. For all of us. That’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be,” Loriano says. There’s a feeling of catharsis to getting all these secrets out into the open. But is there a third person on the line?

A couple of small translation issues hampered my enjoyment: the habit of alternating between calling him Loriano and Bottai (whereas Nives is always that), and the preponderance of sayings (“What’s true is that the business with the nightie has put a bee in my bonnet”), which is presumably to mimic the slang of the original but grates. Still, a good read. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!) [128 pages]

Recommended March Releases: Broder, Fuller, Lamott, Polzin

Three novels that range in tone from carnal allegorical excess to quiet, bittersweet reflection via low-key menace; and essays about keeping the faith in the most turbulent of times.

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

Rachel’s body and mommy issues are major and intertwined: she takes calorie counting and exercise to an extreme, and her therapist has suggested that she take a 90-day break from contact with her overbearing mother. Her workdays at a Hollywood talent management agency are punctuated by carefully regimented meals, one of them a 16-ounce serving of fat-free frozen yogurt from a shop run by Orthodox Jews. One day it’s not the usual teenage boy behind the counter, but his overweight older sister, Miriam. Miriam makes Rachel elaborate sundaes instead of her usual abstemious cups and Rachel lets herself eat them even though it throws her whole diet off. She realizes she’s attracted to Miriam, who comes to fill the bisexual Rachel’s fantasies, and they strike up a tentative relationship over Chinese food and classic film dates as well as Shabbat dinners at Miriam’s family home.

If you’re familiar with The Pisces, Broder’s Women’s Prize-longlisted debut, you should recognize the pattern here: a deep exploration of wish fulfilment and psychological roles, wrapped up in a sarcastic and sexually explicit narrative. Fat becomes not something to fear but a source of comfort; desire for food and for the female body go hand in hand. Rachel says, “It felt like a miracle to be able to eat what I desired, not more or less than that. It was shocking, as though my body somehow knew what to do and what not to do—if only I let it.”

With the help of her therapist, a rabbi that appears in her dreams, and the recurring metaphor of the golem, Rachel starts to grasp the necessity of mothering herself and becoming the shaper of her own life. I was uneasy that Miriam, like Theo in The Pisces, might come to feel more instrumental than real, but overall this was an enjoyable novel that brings together its disparate subjects convincingly. (But is it hot or smutty? You tell me.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

At a glance, the cover for Fuller’s fourth novel seems to host a riot of luscious flowers and fruit, but look closer and you’ll see the daisies are withering and the grapes rotting; there’s a worm exiting the apple and flies are overseeing the decomposition. Just as the image slowly reveals signs of decay, Fuller’s novel gradually unveils the drawbacks of its secluded village setting. Jeanie and Julius Seeder, 51-year-old twins, lived with their mother, Dot, until she was felled by a stroke. They’d always been content with a circumscribed, self-sufficient existence, but now their whole way of life is called into question. Their mother’s rent-free arrangement with the landowners, the Rawsons, falls through, and the cash they keep in a biscuit tin in the cottage comes nowhere close to covering her debts, let alone a funeral.

During the Zoom book launch event, Fuller confessed that she’s “incapable of writing a happy novel,” so consider that your warning of how bleak things will get for her protagonists – though by the end there are pinpricks of returning hope. Before then, though, readers navigate an unrelenting spiral of rural poverty and bad luck, exacerbated by illiteracy and the greed and unkindness of others. One of Fuller’s strengths is creating atmosphere, and there are many images and details here that build the picture of isolation and pathos, such as a piano marooned halfway to a derelict caravan along a forest track and Jeanie having to count pennies so carefully that she must choose between toilet paper and dish soap at the shop.

Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional North Wessex Downs village not far from where I live. I loved spotting references to local places and to folk music – Jeanie and Julius might not have book smarts or successful careers, but they inherited Dot’s love of music and when they pick up a fiddle and guitar they tune in to the ancient magic of storytelling. Much of the novel is from Jeanie’s perspective and she makes for an out-of-the-ordinary yet relatable POV character. I found the novel heavy on exposition, which somewhat slowed my progress through it, but it’s comparable to Fuller’s other work in that it focuses on family secrets, unusual states of mind, and threatening situations. She’s rapidly become one of my favourite contemporary novelists, and I’d recommend this to you if you’ve liked her other work or Fiona Mozley’s Elmet.

With thanks to Penguin Fig Tree for the proof copy for review.

Dusk, Night, Dawn: On Revival and Courage by Anne Lamott

These are Lamott’s best new essays (if you don’t count Small Victories, which reprinted some of her greatest hits) in nearly a decade. The book is a fitting follow-up to 2018’s Almost Everything in that it tackles the same central theme: how to have hope in God and in other people even when the news – Trump, Covid, and climate breakdown – only heralds the worst.

One key thing that has changed in Lamott’s life since her last book is getting married for the first time, in her mid-sixties, to a Buddhist. “How’s married life?” people can’t seem to resist asking her. In thinking of marriage she writes about love and friendship, constancy and forgiveness, none of which comes easy. Her neurotic nature flares up every now and again, but Neal helps to talk her down. Fragments of her early family life come back as she considers all her parents were up against and concludes that they did their best (“How paltry and blocked our family love was, how narrow the bandwidth of my parents’ spiritual lives”).

Opportunities for maintaining quiet faith in spite of the circumstances arise all the time for her, whether it’s a variety show that feels like it will never end, a four-day power cut in California, the kitten inexplicably going missing, or young people taking to the streets to protest about the climate crisis they’re inheriting. A short postscript entitled “Covid College” gives thanks for “the blessings of COVID: we became more reflective, more contemplative.”

The prose and anecdotes feel fresher here than in several of the author’s other recent books. I highlighted quote after quote on my Kindle. Some of these essays will be well worth rereading and deserve to become classics in the Lamott canon, especially “Soul Lather,” “Snail Hymn,” “Light Breezes,” and “One Winged Love.”

I read an advanced digital review copy via NetGalley. Available from Riverhead in the USA and SPCK in the UK.

Brood by Jackie Polzin

Polzin’s debut novel is a quietly touching story of a woman in the Midwest raising chickens and coming to terms with the shape of her life. The unnamed narrator is Everywoman and no one at the same time. As in recent autofiction by Rachel Cusk and Sigrid Nunez, readers find observations of other people (and animals), a record of their behaviour and words; facts about the narrator herself are few and far between, though it is possible to gradually piece together a backstory for her. At one point she reveals, with no fanfare, that she miscarried four months into pregnancy in the bathroom of one of the houses she cleans. There is a bittersweet tone to this short work. It’s a low-key, genuine portrait of life in the in-between stages and how it can be affected by fate or by other people’s decisions.

See my full review at BookBrowse. I was also lucky enough to do an interview with the author.

I read an advanced digital review copy via Edelweiss. Available from Doubleday in the USA. To be released in the UK by Picador tomorrow, April 1st.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,  This is Mann’s second collection, after

This is Mann’s second collection, after