The 2023 Releases I’ve Read So Far

Some reviewers and book bloggers are constantly reading three to six months ahead of what’s out on the shelves, but I tend to get behind on proof copies and read from the library instead. (Who am I kidding? I’m no influencer.)

In any case, I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid review for Foreword, Shelf Awareness, etc. Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet; I’ll give very brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest.

Early in January I’ll follow up with my 20 Most Anticipated titles of the coming year.

My top recommendations so far:

(In alphabetical order)

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise.

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read.

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption.

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019.

Other 2023 releases I’ve read:

(In publication date order; links to the few reviews that are already available online)

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too.

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too.

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart.

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart.

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship.

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on.

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere.

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere.

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness.

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness.

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality.

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality.

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son.

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son.

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight.

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight.

Currently reading:

(In release date order)

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Additional pre-release books on my shelf:

(In release date order)

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any 2023 reads you can recommend already?

Novellas in November, Part 1

This is my second year of joining Laura (Reading in Bed) and others in reading mostly novellas in November. I’ve trawled my shelves and my current library pile for short books, limiting myself to ones of around 150 pages or fewer. First up: four short works of fiction. (I’m at work on various ‘nonfiction novellas’, too.) For the first two I give longer reviews as I got the books from the publishers; the other two are true minis.

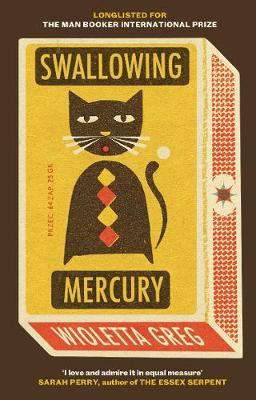

Swallowing Mercury by Wioletta Greg

(translated from the Polish by Eliza Marciniak)

[146 pages]

I heard about this one via the Man Booker International Prize longlist. Quirkiness is particularly common in indie and translated books, I find, and while it’s often off-putting for me, I loved it here. Greg achieves an impressive balance between grim subject matter and simple enjoyment of remembered childhood activities. Her novella is, after all, set in Poland in the 1980s, the last decade of it being a Communist state in the Soviet Union.

The narrator (and autobiographical stand-in?) is Wiolka Rogalówna, who lives with her parents in a moldering house in the fictional town of Hektary. Her father, one of the most striking characters, was arrested for deserting from the army two weeks before she was born, and now works for a paper mill and zealously pursues his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and taxidermy. The signs of their deprivation – really the whole country’s poverty – are subtle: Wiolka has to go selling hand-picked sour cherries with her grandmother at the market even though she’s embarrassed to run into her classmates; she goes out collecting scrap metal with a gang of boys; and she ties up her hair with a rubber band she cut from an inner tube.

The narrator (and autobiographical stand-in?) is Wiolka Rogalówna, who lives with her parents in a moldering house in the fictional town of Hektary. Her father, one of the most striking characters, was arrested for deserting from the army two weeks before she was born, and now works for a paper mill and zealously pursues his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and taxidermy. The signs of their deprivation – really the whole country’s poverty – are subtle: Wiolka has to go selling hand-picked sour cherries with her grandmother at the market even though she’s embarrassed to run into her classmates; she goes out collecting scrap metal with a gang of boys; and she ties up her hair with a rubber band she cut from an inner tube.

Catholicism plays a major role in these characters’ lives: Wiolka wins a blessed figure in a church raffle, the Pope is rumored to be on his way, and a picture of the Black Madonna visits the town. A striking contrast is set up between the threat of molestation – Wiolka is always fending off unwanted advances, it seems – and lighthearted antics like school competitions and going to great lengths to get rare matchbox labels for her collection. This almost madcap element balances out some of the difficulty of her upbringing.

What I most appreciated was the way Greg depicts some universalities of childhood and adolescence, such as catching bugs, having eerie experiences in the dark, and getting one’s first period. This is a book of titled vignettes of just five to 10 pages, but it feels much more expansive than that, capturing the whole of early life. The Polish title translates as “Unripe,” which better reflects the coming-of-age theme; the English translator has gone for that quirk instead.

A favorite passage:

“Then I sat at the table, which was set with plates full of pasta, laid my head down on the surface and felt the pulsating of the wood. In its cracks and knots, christenings, wakes and name-day celebrations were in full swing, and woodworms were playing dodgeball using poppy seeds that had fallen from the crusts of freshly baked bread.”

Thanks to Portobello Books for the free copy for review.

A Field Guide to the North American Family by Garth Risk Hallberg

[126 pages]

Written somewhat in the style of a bird field guide, this is essentially a set of flash fiction stories you have to put together in your mind to figure out what happens to two seemingly conventional middle-class families: the Harrisons and the Hungates, neighbors on Long Island. Frank Harrison dies suddenly in 2008, and the Hungates divorce soon after. Their son Gabe devotes much of his high school years to drug-taking before an accident lands him in a burn unit. Here he’s visited by his girlfriend, Lacey Harrison. Her little brother, Tommy, is a compulsive liar but knows a big secret his late father was keeping from his wife.

Written somewhat in the style of a bird field guide, this is essentially a set of flash fiction stories you have to put together in your mind to figure out what happens to two seemingly conventional middle-class families: the Harrisons and the Hungates, neighbors on Long Island. Frank Harrison dies suddenly in 2008, and the Hungates divorce soon after. Their son Gabe devotes much of his high school years to drug-taking before an accident lands him in a burn unit. Here he’s visited by his girlfriend, Lacey Harrison. Her little brother, Tommy, is a compulsive liar but knows a big secret his late father was keeping from his wife.

The chapters, each just a paragraph or two, are given alphabetical, cross-referenced headings and an apparently thematic photograph. For example, “Entertainment,” one of my favorite stand-alone pieces, opens “In the beginning was the Television. And the Television was large and paneled in plastic made to look like wood. It dwelled in a dim corner of the living room and came on for national news, Cosby, Saturday cartoons, and football.”

This is a Franzen-esque take on family dysfunction and, like City on Fire, is best devoured in large chunks at a time so you don’t lose momentum: as short as this is, I found it easy to forget who the characters were and had to keep referring to the (handy) family tree at the start. Ultimately I found the mixed-media format just a little silly, and the photos often seem to bear little relation to the text. It’s interesting to see how this idea evolved into the mixed-media sections of City on Fire, which is as epic as this is minimalist, though the story line of this novella is so thin as to be almost incidental.

This is a Franzen-esque take on family dysfunction and, like City on Fire, is best devoured in large chunks at a time so you don’t lose momentum: as short as this is, I found it easy to forget who the characters were and had to keep referring to the (handy) family tree at the start. Ultimately I found the mixed-media format just a little silly, and the photos often seem to bear little relation to the text. It’s interesting to see how this idea evolved into the mixed-media sections of City on Fire, which is as epic as this is minimalist, though the story line of this novella is so thin as to be almost incidental.

Favorite lines:

“Depending on parent genotype, the crossbreeding of a Bad Habit and Boredom will result in either Chemistry or Entertainment.”

“Though hardly the most visible member of its kingdom, Love has never been as endangered as conservationists would have us believe, for without it, the Family would cease to function.”

Thanks to Vintage Books for the free copy for review.

The Comfort of Strangers by Ian McEwan

[100 pages]

This is the earliest McEwan work I’ve read (1981). I could see the seeds of some of his classic themes: obsession, sexual and otherwise; the slow building of suspense and awareness until an inevitable short burst of violence. Mary and Colin are a vacationing couple in Venice. One evening they’ve spent so long in bed that by the time they get out all the local restaurants have shut, but a bar-owner takes pity and gives them sustenance, then a place to rest and wash when they get lost and fail to locate their hotel. Soon neighborly solicitude turns into a creepy level of attention. McEwan has a knack for presenting situations that are just odd enough to stand out but not odd enough to provoke an instant recoil, so along with the characters we keep thinking all will turn out benignly. This reminded me of Death in Venice and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

This is the earliest McEwan work I’ve read (1981). I could see the seeds of some of his classic themes: obsession, sexual and otherwise; the slow building of suspense and awareness until an inevitable short burst of violence. Mary and Colin are a vacationing couple in Venice. One evening they’ve spent so long in bed that by the time they get out all the local restaurants have shut, but a bar-owner takes pity and gives them sustenance, then a place to rest and wash when they get lost and fail to locate their hotel. Soon neighborly solicitude turns into a creepy level of attention. McEwan has a knack for presenting situations that are just odd enough to stand out but not odd enough to provoke an instant recoil, so along with the characters we keep thinking all will turn out benignly. This reminded me of Death in Venice and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

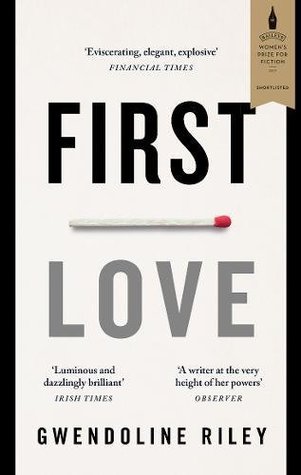

First Love by Gwendoline Riley

[167 pages – on the long side, but I had a library copy to read anyway]

Neve tells us about her testy marriage with Edwyn, a Jekyll & Hyde type who sometimes earns our sympathy for his health problems and other times seems like a verbally abusive misogynist. But she also tells us about her past: her excess drinking, her unpleasant father, her moves between various cities in the north of England and Scotland, a previous relationship that broke down, her mother’s failed marriages, and so on. There’s a lot of very good dialogue in this book – I was reminded of Conversations with Friends – and Neve’s needy mum is a great character, but I wasn’t sure what this all amounts to. As best I can make out, we are meant to question Neve’s self-destructive habits, with Edwyn being just the latest example of a poor, masochistic decision. Every once in a while you get Riley waxing lyrical in a way that suggests she’s a really great author who got stuck with a somber, limited subject: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light, so the outlook was torched; wet bus stop, wet shutters, all deep-dyed.”

Neve tells us about her testy marriage with Edwyn, a Jekyll & Hyde type who sometimes earns our sympathy for his health problems and other times seems like a verbally abusive misogynist. But she also tells us about her past: her excess drinking, her unpleasant father, her moves between various cities in the north of England and Scotland, a previous relationship that broke down, her mother’s failed marriages, and so on. There’s a lot of very good dialogue in this book – I was reminded of Conversations with Friends – and Neve’s needy mum is a great character, but I wasn’t sure what this all amounts to. As best I can make out, we are meant to question Neve’s self-destructive habits, with Edwyn being just the latest example of a poor, masochistic decision. Every once in a while you get Riley waxing lyrical in a way that suggests she’s a really great author who got stuck with a somber, limited subject: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light, so the outlook was torched; wet bus stop, wet shutters, all deep-dyed.”

Other favorite lines:

“An illusion of freedom: snap-twist getaways with no plans: nothing real. I’d given my freedom away. Time and again. As if I had contempt for it. Or was it hopelessness I felt, that I was so negligent? Or did it hardly matter, in fact? … Could I trust myself? Not to make my life a lair.”

It was

It was  I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close.

I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close. These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad.

These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad. Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives.

Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives. So there you have four of the story plots in a nutshell. “Cartagena” is an interesting enough inside look at a Colombian gang, but Le’s strategy for revealing that these characters would be operating in a foreign language is to repeatedly use the construction “X has Y years” for giving ages, which I found annoying. “Meeting Elise” is the painter-with-hemorrhoids one (though I would have titled it “A Big Deal”) and has Henry nervously awaiting his reunion with his teenage daughter, a cello prodigy. There’s a Philip Roth air to that one. “Hiroshima” is brief and dreamy, and works because of the dramatic irony between what readers know and the narrator does not. “The Boat,” the final story, is the promised Vietnam adventure, but took forever to get to. I skimmed/skipped two stories of 50+ pages, “Halflead Bay,” set among Australian teens, and “Tehran Calling.”

So there you have four of the story plots in a nutshell. “Cartagena” is an interesting enough inside look at a Colombian gang, but Le’s strategy for revealing that these characters would be operating in a foreign language is to repeatedly use the construction “X has Y years” for giving ages, which I found annoying. “Meeting Elise” is the painter-with-hemorrhoids one (though I would have titled it “A Big Deal”) and has Henry nervously awaiting his reunion with his teenage daughter, a cello prodigy. There’s a Philip Roth air to that one. “Hiroshima” is brief and dreamy, and works because of the dramatic irony between what readers know and the narrator does not. “The Boat,” the final story, is the promised Vietnam adventure, but took forever to get to. I skimmed/skipped two stories of 50+ pages, “Halflead Bay,” set among Australian teens, and “Tehran Calling.” “How to Make Love to a Physicist,” told in the second person, is about an art teacher scared to embark on a relationship with a seemingly perfect man she meets at a conference. “Dear Sister,” in the form of a long, gossipy letter, is about a tangled set of half-siblings. “Jael” alternates a young teen’s diary entries and her great-grandmother’s fretting over what to do with her wild ward. (The biblical title takes on delicious significance later on.) Multiple characters clash with authority figures about church attendance, with the decision to leave the fold coinciding with claiming autonomy or rejecting hypocrisy.

“How to Make Love to a Physicist,” told in the second person, is about an art teacher scared to embark on a relationship with a seemingly perfect man she meets at a conference. “Dear Sister,” in the form of a long, gossipy letter, is about a tangled set of half-siblings. “Jael” alternates a young teen’s diary entries and her great-grandmother’s fretting over what to do with her wild ward. (The biblical title takes on delicious significance later on.) Multiple characters clash with authority figures about church attendance, with the decision to leave the fold coinciding with claiming autonomy or rejecting hypocrisy. I should have known, after reading When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow (an obvious satire on Richard Dawkins’s atheism) in 2017, that Dan Rhodes’s humour wasn’t for me. However, I generally love flash fiction so thought I might as well give these 101 stories – all about 100 words, or one paragraph, long – a go when I found a copy in a giveaway box across the street. Each has a one-word title, proceeding alphabetically from A to W, and many begin “My girlfriend…” as an unnamed bloke reflects on a relationship. Most of the setups are absurd; the girlfriends’ names (Foxglove, Miracle, Nightjar) tell you so, if nothing else.

I should have known, after reading When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow (an obvious satire on Richard Dawkins’s atheism) in 2017, that Dan Rhodes’s humour wasn’t for me. However, I generally love flash fiction so thought I might as well give these 101 stories – all about 100 words, or one paragraph, long – a go when I found a copy in a giveaway box across the street. Each has a one-word title, proceeding alphabetically from A to W, and many begin “My girlfriend…” as an unnamed bloke reflects on a relationship. Most of the setups are absurd; the girlfriends’ names (Foxglove, Miracle, Nightjar) tell you so, if nothing else.

Four of these 10 stories first appeared in the London Review of Books, and another four in the Guardian. Most interestingly, the opening story, “Sorry to Disturb,” about a bored housewife trying to write a novel while in Saudi Arabia with her husband in 1983–4, was published in the LRB with the subtitle “A Memoir.” That it’s one of the best few ‘stories’ here doesn’t negate Mantel’s fictional abilities so much as prove her talent for working in the short form.

Four of these 10 stories first appeared in the London Review of Books, and another four in the Guardian. Most interestingly, the opening story, “Sorry to Disturb,” about a bored housewife trying to write a novel while in Saudi Arabia with her husband in 1983–4, was published in the LRB with the subtitle “A Memoir.” That it’s one of the best few ‘stories’ here doesn’t negate Mantel’s fictional abilities so much as prove her talent for working in the short form. I liked this even more than Simpson’s first book, Four Bare Legs in a Bed, which I reviewed last year. The themes include motherhood (starting, in a couple of cases, in one’s early 40s), death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. There’s gentle humor and magic to these stories that tempers some of the sadness. I especially liked “The Door,” about a grieving woman looking to restore her sense of security after a home break-in, “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff (one of two Christmas-themed stories here) in which a woman is shown how her negative thoughts and obsession with the past are damaging her, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour circular walk during her lunch break and documenting her thoughts about everything from pregnancy to a nonagenarian friend’s funeral. [The UK title of the collection is Constitutional.]

I liked this even more than Simpson’s first book, Four Bare Legs in a Bed, which I reviewed last year. The themes include motherhood (starting, in a couple of cases, in one’s early 40s), death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. There’s gentle humor and magic to these stories that tempers some of the sadness. I especially liked “The Door,” about a grieving woman looking to restore her sense of security after a home break-in, “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff (one of two Christmas-themed stories here) in which a woman is shown how her negative thoughts and obsession with the past are damaging her, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour circular walk during her lunch break and documenting her thoughts about everything from pregnancy to a nonagenarian friend’s funeral. [The UK title of the collection is Constitutional.]

Edith and Helen have a rivalry as old as the Bible, based around an inheritance that Helen stole to reopen her husband’s family brewery, instead of sharing it with Edith. Ever since, Edith has had to work minimum-wage jobs at nursing homes and fast food restaurants to make ends meet. When Diana comes to live with her as a teenager, she, too, works hard to contribute to the family, but then gets caught up in a dodgy money-making scheme. It’s in penance for this error that she starts working at a local brewery, but beer soon becomes as much of an obsession for Diana as it once was for her great-aunt Helen.

Edith and Helen have a rivalry as old as the Bible, based around an inheritance that Helen stole to reopen her husband’s family brewery, instead of sharing it with Edith. Ever since, Edith has had to work minimum-wage jobs at nursing homes and fast food restaurants to make ends meet. When Diana comes to live with her as a teenager, she, too, works hard to contribute to the family, but then gets caught up in a dodgy money-making scheme. It’s in penance for this error that she starts working at a local brewery, but beer soon becomes as much of an obsession for Diana as it once was for her great-aunt Helen.

I Want to Show You More by Jamie Quatro – I read the first two stories. “Decomposition,” about a woman’s lover magically becoming a physical as well as emotional weight on her and her marriage, has an interesting structure as well as second-person narration, but I fear the collection as a whole will just be a one-note treatment of a woman’s obsession with her affair.

I Want to Show You More by Jamie Quatro – I read the first two stories. “Decomposition,” about a woman’s lover magically becoming a physical as well as emotional weight on her and her marriage, has an interesting structure as well as second-person narration, but I fear the collection as a whole will just be a one-note treatment of a woman’s obsession with her affair. Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett – Elegant stories about history, science and human error. Barrett is similar to A.S. Byatt in her style and themes, which are familiar to me from my reading of Archangel. This won a National Book Award in 1996.

Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett – Elegant stories about history, science and human error. Barrett is similar to A.S. Byatt in her style and themes, which are familiar to me from my reading of Archangel. This won a National Book Award in 1996.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)  The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.  Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.

Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.

Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for

Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for  How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.”

How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.” At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.

At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.