Three on a Theme: Raven Books for Halloween

It’s been a while since I’ve done a Three on a Theme post (over eight months, in fact). I thought it would be fun to round up a few nonfiction books about ravens that I’ve read over the last year or so – I just finished the Skaife last night.

I tend to associate ravens with Halloween because of Edgar Allan Poe’s eerie poem “The Raven.” In eighth grade English class we had the challenge of memorizing as much of this multi-stanza poem as possible. A friend and I took this very seriously and recited the whole thing, I think (or at least enough to be obnoxious), in front of the class. I can still conjure up big chunks of it in my memory: “Once upon a midnight dreary / while I pondered, weak and weary / over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore…” The rhymes and alliteration make it a real earworm.

The Book of the Raven: Corvids in Art and Legend by Angus Hyland and Caroline Roberts (2021)

I loved the art, which ranges from the well-known (Van Gogh) to the recent and obscure and includes etchings, paintings and photographs, and wood carvings. The text was less illuminating, relying on some very familiar points of reference like Aesop’s fables, Norse myths, Poe’s “The Raven,” and so on. It’s slightly confusing that the authors decided to lump all corvids together as it suits them, so they include legends and poems associated with crows and magpies as well as ravens.

I loved the art, which ranges from the well-known (Van Gogh) to the recent and obscure and includes etchings, paintings and photographs, and wood carvings. The text was less illuminating, relying on some very familiar points of reference like Aesop’s fables, Norse myths, Poe’s “The Raven,” and so on. It’s slightly confusing that the authors decided to lump all corvids together as it suits them, so they include legends and poems associated with crows and magpies as well as ravens.

Most pieces are only one page and have an image facing, as well as at least two pages of wordless spreads between them. There are also shorter quotations embedded in some of the illustrations. Gothic font abounds and there is an overall black, white and red colour scheme. I was glad to be reminded that Charles Dickens’s pet raven, Grip III, was stuffed and is now in display in the Free Library of Philadelphia – that will be a sight to seek out on my next trip there. I also enjoyed learning about Jimmy, a Hollywood raven who appeared in over 1,000 films between 1938 and 1954, including It’s a Wonderful Life. This was a surprise Christmas gift, and a fun enough coffee table read.

A Shadow Above: The Fall and Rise of the Raven by Joe Shute (2018)

Ravens are freighted with such symbolism that people attribute special significance to their presence or absence. In parts of Britain, they were persecuted to the point of extirpation, but in recent years they have been finding new strongholds everywhere from sea cliffs and abandoned quarries to the New Forest and city centres. Travelling around the country, Shute learns how mythology reflects humans’ historical relationships with the birds and meets with those who hate and shoot ravens (farmers whose lambs and piglets they gang up to kill) as well as those who rehabilitate them or live with them as companions. It’s a balanced and well informed book, if a little by-the-numbers in its approach.

Ravens are freighted with such symbolism that people attribute special significance to their presence or absence. In parts of Britain, they were persecuted to the point of extirpation, but in recent years they have been finding new strongholds everywhere from sea cliffs and abandoned quarries to the New Forest and city centres. Travelling around the country, Shute learns how mythology reflects humans’ historical relationships with the birds and meets with those who hate and shoot ravens (farmers whose lambs and piglets they gang up to kill) as well as those who rehabilitate them or live with them as companions. It’s a balanced and well informed book, if a little by-the-numbers in its approach.

A terrific final paragraph: “Watching the birds dive under the fizzing pylon wires, I also realise just how much we need them close by. To provide us with a glimpse of wildness in a world hell-bent on civilising its furthest reaches, while at the same time inching closer towards the abyss. The raven will always continue to represent our own projections. This modern omen remains as yet ill-defined; our shared futures unresolved.” (Public library)

The Ravenmaster by Christopher Skaife (2018)

A newspaper/magazine feature I enjoy is when a journalist interviews someone with a really random job – you know, like a cat food taste tester or the guy who cleans the Tube tunnels in London or empties the loos after Glastonbury Festival. This memoir was moderately interesting in the same sort of way.

How does one get to be raven keeper at the Tower of London? In Skaife’s case, via the military. He was an indifferent student so joined the Army young and served for 24 years, including as a Drum Major and in Northern Ireland, before becoming a Yeoman Warder. He’s the sixth Ravenmaster (a new title after 1946), in post since 2011. He was always interested in history and as a mature student took a degree in archaeology, so he’s well suited to introducing the Tower to visitors. I appreciated his description of the challenge of making the experience fresh each time even though for him it’s become daily drudgery: “Doing a really great tour is like being a jazz musician: a moment’s improvisation based on a lifetime’s experience.”

How does one get to be raven keeper at the Tower of London? In Skaife’s case, via the military. He was an indifferent student so joined the Army young and served for 24 years, including as a Drum Major and in Northern Ireland, before becoming a Yeoman Warder. He’s the sixth Ravenmaster (a new title after 1946), in post since 2011. He was always interested in history and as a mature student took a degree in archaeology, so he’s well suited to introducing the Tower to visitors. I appreciated his description of the challenge of making the experience fresh each time even though for him it’s become daily drudgery: “Doing a really great tour is like being a jazz musician: a moment’s improvisation based on a lifetime’s experience.”

Seeing to seven resident ravens’ needs is also repetitive and has to be done in the same way, on time, every day if he doesn’t want revolt – when he once tried to put them to bed in their cages in a different order, Merlina (who also plays dead and engages in hide-and-seek) led him a merry dance and he ended up falling into the moat. He’s sometimes learned the hard way, as when a raven died when it hid in scaffolding and then plunged to the ground – he realized he’d clipped its wings too severely. Other birds have been lost to foxes, so he’s gotten in the habit of feeding foxes in one spot so they’ll stay away from the raven enclosure.

It’s a good-natured, anecdotal book, but didn’t teach me anything I didn’t already know about ravens from various other books; it reports pretty entry-level information on bird intelligence, communication, and representations in popular culture. I most liked hearing about the ravens’ individual personalities and the little mishaps and surprises he’s experienced in dealing with them. But many chapters feel thrown together in an arbitrary order, and Skaife’s writing about his life before the Tower doesn’t add anything. So while I envy him living in such a history-saturated place and would probably like to tour the Tower one day, the book wasn’t the intriguing insider’s account I was looking for. A ghostwriter or extra helping editorial hand wouldn’t have gone amiss, honestly. (A gift from my wish list a couple of Christmases ago)

If you read just one … A Shadow Above by Joe Shute was the stand-out for me.

My next raven-themed read will be: Ravens in Winter by Bernd Heinrich.

R.I.P. Part II: Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver

A rainy and blustery Halloween here in southern England, with a second lockdown looming later in the week. I haven’t done anything special to mark Halloween since I was in college, though this year a children’s book inspired me to have some fun with our veg box vegetables for this photo shoot. Just call us Christopher Pumpkin and Rebecca Red Cabbage.

It’s my third year participating in R.I.P. (Readers Imbibing Peril). In each of those three years I’ve reviewed a novel by Michelle Paver. First it was Thin Air, then Dark Matter – two 1930s ghost stories of men undertaking an adventure in a bleak setting (the Himalayas and the Arctic, respectively). I found a copy of her latest in the temporary Little Free Library I started to keep the neighborhood going while the public library was closed during the first lockdown.

Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver (2019)

There’s a Gothic flavor to this story of a mentally unstable artist and his teenage daughter. Edmund Stearne is obsessed with the writings of Medieval mystic Alice Pyett (based on Margery Kempe) and with a Bosch-like Doom painting recently uncovered at the local church. Serving as his secretary after her mother’s death, Maud reads his journals to follow his thinking – but also uncovers unpleasant truths about his sister’s death and his relationship with the servant girl. As Maud tries to prevent her father from acting on his hallucinations of demons and witches rising from the Suffolk Fens, she falls in love with someone beneath her class. Only in the 1960s framing story, which has a journalist and scholar digging into what really happened at Wake’s End in 1913, does it become clear how much Maud gave up.

There’s a Gothic flavor to this story of a mentally unstable artist and his teenage daughter. Edmund Stearne is obsessed with the writings of Medieval mystic Alice Pyett (based on Margery Kempe) and with a Bosch-like Doom painting recently uncovered at the local church. Serving as his secretary after her mother’s death, Maud reads his journals to follow his thinking – but also uncovers unpleasant truths about his sister’s death and his relationship with the servant girl. As Maud tries to prevent her father from acting on his hallucinations of demons and witches rising from the Suffolk Fens, she falls in love with someone beneath her class. Only in the 1960s framing story, which has a journalist and scholar digging into what really happened at Wake’s End in 1913, does it become clear how much Maud gave up.

There are a lot of appealing elements in this novel, including Maud’s pet magpie, the travails of her constantly pregnant mother (based on the author’s Belgian great-grandmother), the information on early lobotomies, and the mixture of real (eels!) and imagined threats encountered at the fen. The focus on a female character is refreshing after her two male-dominated ghost stories. But as atmospheric and readable as Paver’s writing always is, here the plot sags, taking too much time over each section and filtering too much through Stearne’s journal. After three average ratings in a row, I doubt I’ll pick up another of her books in the future.

My rating:

My top R.I.P. read this year was Sisters by Daisy Johnson, followed by 666 Charing Cross by Paul Magrs (both reviewed here).

Have you been reading anything spooky for Halloween?

Autumn Reading: The Pumpkin Eater and More

I’ve been gearing up for Novellas in November with a few short autumnal reads, as well as some picture books bedecked with fallen leaves, pumpkins and warm scarves.

An Event in Autumn by Henning Mankell (2004)

[Translated from the Swedish by Laurie Thompson, 2014]

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

Of course things aren’t going to go smoothly with this venture. You have to suspend disbelief when reading about the adventures of investigators; it’s like they attract corpses. So it’s not much of a surprise that while he’s walking the grounds of this house he finds a human hand poking out of the soil, and eventually the remains of a middle-aged couple are unearthed. The rest of the book is about finding out what happened on the property at the time of the Second World War. Wallander says he doesn’t believe in ghosts, but victims of wrongful death are as persistent as ghosts: they won’t be ignored until answers are found.

This was a quick and easy read, but nothing about it (setting, topics, characterization, prose) made me inclined to read further in the author’s work.

My rating:

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer (1962)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, they’re building a glass tower as their countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood.

An excellent 2011 introduction by Daphne Merkin reveals how autobiographical this seventh novel was for Mortimer. But her backstory isn’t a necessary prerequisite for appreciating this razor-sharp period piece. You get a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility and chafing at the thought that she’s had no choice in what life has dealt her. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humor and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind. I was reminded of Janice Galloway’s The Trick Is to Keep Breathing and Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. If you’re still looking for ideas for Novellas in November, I recommend it highly.

My rating:

Snow in Autumn by Irène Némirovsky (1931)

[Translated from the French by Sandra Smith, 2007]

(Classic of the Month, #2)

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

My rating:

Plus a quartet of children’s picture books from the library:

Pumpkin Soup by Helen Cooper: A cat, a squirrel and a duck live together in a teapot-shaped cabin in the woods. They cook pumpkin soup and make music in perfect harmony, each cheerfully playing their assigned role, until the day Duck decides he wants to be the one to stir the soup. A vicious quarrel ensues, and Duck leaves. Nothing is the same without the whole trio there. After some misadventures, when the gang is finally back together, they’ve learned their lesson about flexibility … or have they? Adorably mischievous.

Moomin and the Golden Leaf by Richard Dungworth: Beware: this is not actually a Tove Jansson plot, although her name is, misleadingly, printed on the cover (under tiny letters “Based on the original stories by…”). Autumn has come to Moominvalley. Moomin and Sniff find a golden leaf while they’re out foraging. He sets out to find the golden tree it must have come from, but the source is not what he expected. Meanwhile, the rest are rehearsing a play to perform at the Autumn Ball before a seasonal feast. This was rather twee and didn’t capture Jansson’s playful, slightly melancholy charm.

Little Owl’s Orange Scarf by Tatyana Feeney: Ungrateful Little Owl thinks the orange scarf his mother knit for him is too scratchy. He tries “very hard to lose his new scarf” and finally manages it on a trip to the zoo. His mother lets him choose his replacement wool, a soft green. I liked the color blocks and the simple design, and the final reveal of what happened to the orange scarf is cute, but I’m not sure the message is one to support (pickiness vs. making do with what you have).

Christopher Pumpkin by Sue Hendra and Paul Linnet: The witch of Spooksville needs help preparing for a big party, so brings a set of pumpkins to life. Something goes a bit wrong with the last one, though: instead of all things ghoulish, Christopher Pumpkin loves all things fun. He bakes cupcakes instead of stirring gross potions and strums a blue ukulele instead of inducing screams. The witch threatens to turn Chris into soup if he can’t be scary. The plan he comes up with is the icing on the cake of a sweet, funny book delivered in rhyming couplets. Good for helping kids think about stereotypes and how we treat those who don’t fit in.

This was among my

This was among my  All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!) This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues. I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults ( Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

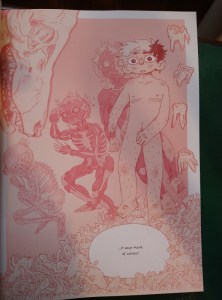

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it. This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award. Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 (

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 ( I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels (

I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels ( The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after

The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after  This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which

This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which  This came highly recommended by

This came highly recommended by  I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

If you find unreliable narrators delicious, you’re in the right place. The mood is confessional, yet Laurie is anything but confiding. Occasionally she apologizes for her behaviour: “I realise this does not sound very sane” is one of her concessions to readers’ rationality. So her drinking problem doesn’t become evident until nearly halfway through, and a bombshell is still to come. It’s the key to understanding our protagonist and why she’s acted this way.

If you find unreliable narrators delicious, you’re in the right place. The mood is confessional, yet Laurie is anything but confiding. Occasionally she apologizes for her behaviour: “I realise this does not sound very sane” is one of her concessions to readers’ rationality. So her drinking problem doesn’t become evident until nearly halfway through, and a bombshell is still to come. It’s the key to understanding our protagonist and why she’s acted this way. This sledgehammer of a short Argentinian novel has a simple premise: not long ago, animals were found to be infected with a virus that made them toxic to humans. During the euphemistic “Transition,” all domesticated and herd animals were killed and the roles they once held began to be filled by humans – hunted, sacrificed, butchered, scavenged, cooked and eaten. A whole gastronomic culture quickly developed around cannibalism.

This sledgehammer of a short Argentinian novel has a simple premise: not long ago, animals were found to be infected with a virus that made them toxic to humans. During the euphemistic “Transition,” all domesticated and herd animals were killed and the roles they once held began to be filled by humans – hunted, sacrificed, butchered, scavenged, cooked and eaten. A whole gastronomic culture quickly developed around cannibalism. I reviewed the five female-penned ghost stories for R.I.P. back in

I reviewed the five female-penned ghost stories for R.I.P. back in  This was my fourth of Hill’s classic ghost stories, after The Woman in Black, The Man in the Picture and Dolly. They’re always concise and so fluently written that the storytelling voice feels effortless. I wondered if this one might have been inspired by “The Ghost of a Hand” (above). It doesn’t feature a disembodied hand, per se, but the presence of a young boy who slips his hand into antiquarian book dealer Adam Snow’s when he stops at an abandoned house in the English countryside, and again when he goes to a French monastery to purchase a Shakespeare First Folio. Each time, Adam feels the ghost is pulling him to throw himself into a pond. When Adam confides in the monks and in his brother, he gets different advice. A pleasant and very quick read, if a little predictable. (Free from a neighbour)

This was my fourth of Hill’s classic ghost stories, after The Woman in Black, The Man in the Picture and Dolly. They’re always concise and so fluently written that the storytelling voice feels effortless. I wondered if this one might have been inspired by “The Ghost of a Hand” (above). It doesn’t feature a disembodied hand, per se, but the presence of a young boy who slips his hand into antiquarian book dealer Adam Snow’s when he stops at an abandoned house in the English countryside, and again when he goes to a French monastery to purchase a Shakespeare First Folio. Each time, Adam feels the ghost is pulling him to throw himself into a pond. When Adam confides in the monks and in his brother, he gets different advice. A pleasant and very quick read, if a little predictable. (Free from a neighbour) Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror” appears in Kink (2021), a short story anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. (I requested it from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Machado and

Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror” appears in Kink (2021), a short story anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. (I requested it from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Machado and  The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest)

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest) I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf.

I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf. The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)

The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)  The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)

The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)  This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

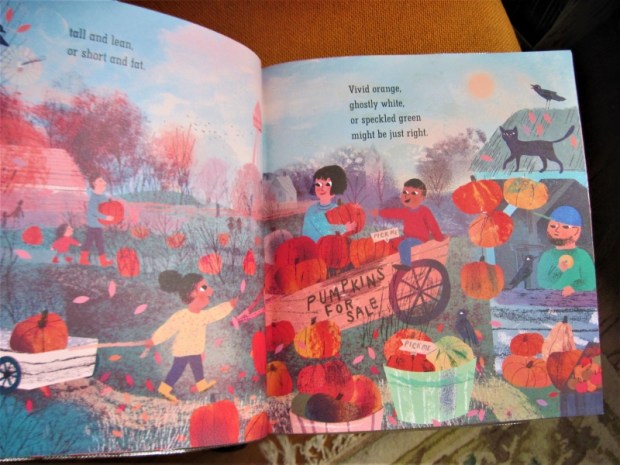

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)  Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

The first section, “After,” responds to the events of 2020; six of its poems were part of a “Twelve Days of Lockdown” commission. Fox remembers how sinister a cougher at a public event felt on 13th March and remarks on how quickly social distancing came to feel like the norm, though hikes and wild swimming helped her to retain a sense of possibility. I especially liked “Pharmacopoeia,” which opens the collection and looks back to the Black Death that hit Amsterdam in 1635 – “suddenly the plagues / are the most interesting parts / of a city’s history.” “Returns” plots her next trip to a bookshop (“The plague books won’t be in yet, / but the dystopia section will be well stocked / … I spend fifty pounds I no longer had last time, will spend another fifty next. / Feeling I’m preserving an ecology, a sort of home”), while “The Funerals” wryly sings the glories of a spring the deceased didn’t get to see.

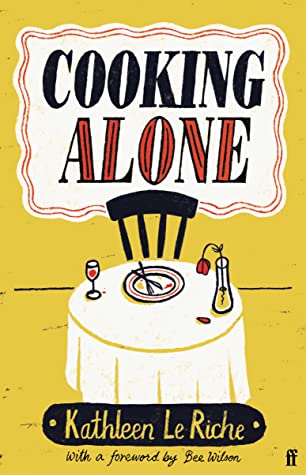

The first section, “After,” responds to the events of 2020; six of its poems were part of a “Twelve Days of Lockdown” commission. Fox remembers how sinister a cougher at a public event felt on 13th March and remarks on how quickly social distancing came to feel like the norm, though hikes and wild swimming helped her to retain a sense of possibility. I especially liked “Pharmacopoeia,” which opens the collection and looks back to the Black Death that hit Amsterdam in 1635 – “suddenly the plagues / are the most interesting parts / of a city’s history.” “Returns” plots her next trip to a bookshop (“The plague books won’t be in yet, / but the dystopia section will be well stocked / … I spend fifty pounds I no longer had last time, will spend another fifty next. / Feeling I’m preserving an ecology, a sort of home”), while “The Funerals” wryly sings the glories of a spring the deceased didn’t get to see. For instance, “The Grass Widower,” while his wife is away visiting her mother, indulges his love of seafood and learns how to wash up effectively. A convalescent plans the uncomplicated meals she’ll fix, including lots of egg dishes and some pleasingly dated fare like “junket” and cherries in brandy. A brother and sister, students left on their own for a day, try out all the different pancakes and quick breads in their repertoire. The bulk of the actual meal ideas come in a chapter called “The Happy Potterer,” whom Le Riche styles as a friend of hers named Flora who wrote out all her recipes on cards collected in an envelope. I enjoyed some of the little notes to self in this section: appended to a recipe for kidney and mushrooms, “Keep a few back for mushrooms-on-toast next day for a mid-morning snack”; “Forgive yourself if you have to use margarine instead of butter for frying.”

For instance, “The Grass Widower,” while his wife is away visiting her mother, indulges his love of seafood and learns how to wash up effectively. A convalescent plans the uncomplicated meals she’ll fix, including lots of egg dishes and some pleasingly dated fare like “junket” and cherries in brandy. A brother and sister, students left on their own for a day, try out all the different pancakes and quick breads in their repertoire. The bulk of the actual meal ideas come in a chapter called “The Happy Potterer,” whom Le Riche styles as a friend of hers named Flora who wrote out all her recipes on cards collected in an envelope. I enjoyed some of the little notes to self in this section: appended to a recipe for kidney and mushrooms, “Keep a few back for mushrooms-on-toast next day for a mid-morning snack”; “Forgive yourself if you have to use margarine instead of butter for frying.” Chang and Christa, the subjects of the book’s first two sections – accounting for about half the length – were opposites and had a volatile relationship. Their home in the New York City projects was an argumentative place the narrator was eager to escape. She felt she never knew her father, a humourless man who lost touch with Chinese culture. He worked on the kitchen staff of a hospital and never learned English properly. Christa, by contrast, was fastidious about English grammar but never lost her thick accent. An obstinate and contradictory woman, she resented her lot in life and never truly loved Chang, but was good with her hands and loved baking and sewing for her daughters.

Chang and Christa, the subjects of the book’s first two sections – accounting for about half the length – were opposites and had a volatile relationship. Their home in the New York City projects was an argumentative place the narrator was eager to escape. She felt she never knew her father, a humourless man who lost touch with Chinese culture. He worked on the kitchen staff of a hospital and never learned English properly. Christa, by contrast, was fastidious about English grammar but never lost her thick accent. An obstinate and contradictory woman, she resented her lot in life and never truly loved Chang, but was good with her hands and loved baking and sewing for her daughters. Thammavongsa pivoted from poetry to short stories and won Canada’s Giller Prize for this debut collection that mostly explores the lives of Laotian immigrants and refugees in a North American city. The 14 stories are split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, many of them narrated by young women remembering how they and their parents adjusted to an utterly foreign culture. The title story and “Chick-A-Chee!” are both built around a misunderstanding of the English language – the latter is a father’s approximation of what his children should say on doorsteps on Halloween. Television soaps and country music on the radio are ways to pick up more of the language. Farm and factory work are de rigueur, but characters nurture dreams of experiences beyond menial labour – at least for their children.

Thammavongsa pivoted from poetry to short stories and won Canada’s Giller Prize for this debut collection that mostly explores the lives of Laotian immigrants and refugees in a North American city. The 14 stories are split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, many of them narrated by young women remembering how they and their parents adjusted to an utterly foreign culture. The title story and “Chick-A-Chee!” are both built around a misunderstanding of the English language – the latter is a father’s approximation of what his children should say on doorsteps on Halloween. Television soaps and country music on the radio are ways to pick up more of the language. Farm and factory work are de rigueur, but characters nurture dreams of experiences beyond menial labour – at least for their children.