Three on a Theme: Frost Fairs Books

Here in southern England, we’ve just had a couple of weeks of hard frost. The local canal froze over for a time; the other day when I thought it had all thawed, a pair of mallard ducks surprised me by appearing to walk on water. In previous centuries, the entire Thames has been known to freeze through central London. (I’d like to revisit Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for a 17th-century scene of that.) This thematic trio of a children’s book, a historical novel, and a poetry collection came together rather by accident: I already had the poetry collection on my shelf, then saw frost fairs referenced in the blurb of the novel, and later spotted the third book while shelving in the children’s section of the library.

A Night at the Frost Fair by Emma Carroll (2021)

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

A sickly little boy named Eddie is her tour guide to the games, rides and snacks on offer here in 1788, but there’s a man around who wants to keep him from enjoying the fair. Maya hopes to help Eddie, and Gran, all while figuring out what the gift parcel means. A low page count meant this felt pretty thin, with everything wrapped up too soon. The problem, really, was that – believe it or not – this isn’t the first middle-grade time-slip historical fantasy novel about frost fairs that I’ve read; the other, Frost by Holly Webb, was better. Sam Usher’s Quentin Blake-like illustrations are a bonus, though. (Public library)

The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (2022)

This has been catalogued as science fiction by my library system, but I’d be more likely to describe it as historical fiction with a touch of magic realism, similar to The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock or Things in Jars. I loved the way the action is bookended by the frost fairs of 1789 and 1814. There’s a whiff of the fairy tale in the setup: when we meet Neva, she’s a little girl whose parents operate one of the fair’s attractions, a chess-playing bear. She knows, like no one else seems to, that the ice is shifting and it’s not safe to stay by the Thames. When the predicted tragedy comes, she’s left an orphan and adopted by Victor Friezland, a clockmaker who shares her Russian heritage. He lives in a wonderfully peculiar house made out of ship parts and, between him, Neva, the housekeeper Elise, and other servants, friends and neighbours, they form a delightful makeshift family.

Neva predicts the weather faultlessly, even years ahead. It’s somewhere between synaesthetic and mystical, this ability to hear the ice speaking and see what the clouds hold. While others in their London circle engage in early meteorological prediction, her talent is different. Victor decides to harness it as an attraction, developing “The Weather Woman” as first an automaton and then a magic lantern show, both with Neva behind the scenes giving unerring forecasts. At the same time, Neva brings her childhood imaginary friend to life, dressing in men’s clothing and appearing as Victor’s business partner, Eugene Jonas, in public.

These various disguises are presented as the only way that a woman could be taken seriously in the early 19th century. Gardner is careful to note that Neva does not believe she is, or seek to become, a man; “She thinks she’s been born into the wrong time, not necessarily the wrong sex. As for her mind, that belongs to a different world altogether.” (Whereas there is a trans character and a couple of queer ones; it would also have been interesting for Gardner to take further the male lead’s attraction to Eugene Jonas.) From her early teens on, she’s declared that she doesn’t intend to marry or have children, but in what I suspect is a trope of romance fiction, she changes her tune when she meets the right man. This was slightly disappointing, yet just one of several satisfying matches made over the course of this rollicking story.

London charms here despite its Dickensian (avant la lettre) grime – mudlarks and body snatchers, gambling and trickery, gloomy pubs and shipwrecks, weaselly lawyers and high-society soirees. The plot moves quickly and holds a lot of surprises and diverting secondary characters. While the novel could have done with some trimming – something I’d probably say about the majority of 450-pagers – I remained hooked and found it fun and racy. You’ll want to stick around for a terrific late set-piece on the ice. Gardner had a career in theatre costume design before writing children’s books. I’ll also try her teen novel, I, Coriander. (Public library)

[Two potential anachronisms: “Hold your horses” (p. 202) and calling someone “a card” (p. 209) – both slang uses that more likely date from the 1830s or 1840s.]

The Frost Fairs by John McCullough (2010)

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

Overnight the Thames begins to move again.

The ice beneath the frost fair cracks. Tents,

merry-go-rounds and bookstalls glide about

On islands given up for lost. They race,

switch places, touch—the printing press nuzzling

the swings—then part, slip quietly under.

I also liked the wordplay of “The Dictionary Man,” the alliteration and English summer setting of “Miss Fothergill Observes a Snail,” and the sibilance versus jarringly violent imagery of “Severance.” However, it was hard to detect links that would create overall cohesion in the book. (Purchased directly from Salt Publishing)

The 2023 Releases I’ve Read So Far

Some reviewers and book bloggers are constantly reading three to six months ahead of what’s out on the shelves, but I tend to get behind on proof copies and read from the library instead. (Who am I kidding? I’m no influencer.)

In any case, I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid review for Foreword, Shelf Awareness, etc. Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet; I’ll give very brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest.

Early in January I’ll follow up with my 20 Most Anticipated titles of the coming year.

My top recommendations so far:

(In alphabetical order)

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise.

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise. ![]()

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read. ![]()

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption.

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption. ![]()

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019. ![]()

Other 2023 releases I’ve read:

(In publication date order; links to the few reviews that are already available online)

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too.

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too. ![]()

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart.

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart. ![]()

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship.

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship. ![]()

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on. ![]()

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere.

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere. ![]()

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness.

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness. ![]()

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality.

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality. ![]()

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son.

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son. ![]()

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight.

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight. ![]()

Currently reading:

(In release date order)

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Additional pre-release books on my shelf:

(In release date order)

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any 2023 reads you can recommend already?

Book Serendipity, Mid-October to Mid-December 2022

The last entry in this series for the year. Those of you who join me for Love Your Library, note that I’ll host it on the 19th this month to avoid the holidays. Other than that, I don’t know how many more posts I’ll fit in before my year-end coverage (about six posts of best-of lists and statistics). Maybe I’ll manage a few more backlog reviews and a thematic roundup.

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Tom Swifties (a punning joke involving the way a quotation is attributed) in Savage Tales by Tara Bergin (“We get a lot of writers in here, said the rollercoaster operator lowering the bar”) and one of the stories in Birds of America by Lorrie Moore (“Would you like a soda? he asked spritely”).

- Prince’s androgynous symbol was on the cover of Dickens and Prince by Nick Hornby and is mentioned in the opening pages of Shameless by Nadia Bolz-Weber.

- Clarence Thomas is mentioned in one story of Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Encore by May Sarton. (A function of them both dating to the early 1990s!)

- A kerfuffle over a ring belonging to the dead in one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- Excellent historical fiction with a 2023 release date in which the amputation of a woman’s leg is a threat or a reality: one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland.

- More of a real-life coincidence, this one: I was looking into Paradise, Piece by Piece by Molly Peacock, a memoir I already had on my TBR, because of an Instagram post I’d read about books that were influential on a childfree woman. Then, later the same day, my inbox showed that Molly Peacock herself had contacted me through my blog’s contact form, offering a review copy of her latest book!

- Reading nonfiction books titled The Heart of Things (by Richard Holloway) and The Small Heart of Things (by Julian Hoffman) at the same time.

- A woman investigates her husband’s past breakdown for clues to his current mental health in The Fear Index by Robert Harris and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

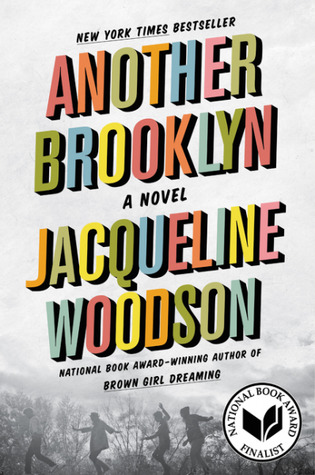

- “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” is a repeated phrase in Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson, as it was in Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin.

- Massive, much-anticipated novel by respected author who doesn’t publish very often, and that changed names along the way: John Irving’s The Last Chairlift (2022) was originally “Darkness as a Bride” (a better title!); Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (2023) started off as “The Maramon Convention.” I plan to read the Verghese but have decided against the Irving.

- Looting and white flight in New York City in Feral City by Jeremiah Moss and Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson.

- Two bereavement memoirs about a loved one’s death from pancreatic cancer: Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik and Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner.

- The Owl and the Pussycat of Edward Lear’s poem turn up in an update poem by Margaret Atwood in her collection The Door and in Anna James’s fifth Pages & Co. book, The Treehouse Library.

- Two books in which the author draws security attention for close observation of living things on the ground: Where the Wildflowers Grow by Leif Bersweden and The Lichen Museum by A. Laurie Palmer.

- Seal and human motherhood are compared in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer, two 2023 memoirs I’m enjoying a lot.

- Mystical lights appear in Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (the Northern Lights, there) and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer.

- St Vitus Dance is mentioned in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and Robin by Helen F. Wilson.

- The history of white supremacy as a deliberate project in Oregon was a major element in Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk, which I read earlier in the year, and has now recurred in The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

For Thy Great Pain… and Ti Amo for #NovNov22

On Friday evening we went to see Aqualung give his first London show in 12 years. (Here’s his lovely new song “November.”) I like travel days because I tend to get loads of reading done on my Kindle, and this was no exception: I read both of the below novellas, plus two-thirds of a poetry collection. Novellas aren’t always quick reads, but these were.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie (2023)

Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on when she posits that Margery visited Julian in her cell and took into safekeeping the manuscript of her “shewings.” I finished reading Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love earlier this year and, apart from a couple of biographical details (she lost her husband and baby daughter to an outbreak of plague, and didn’t leave her cell in Norwich for 23 years), this added little to my experience of her work.

Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on when she posits that Margery visited Julian in her cell and took into safekeeping the manuscript of her “shewings.” I finished reading Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love earlier this year and, apart from a couple of biographical details (she lost her husband and baby daughter to an outbreak of plague, and didn’t leave her cell in Norwich for 23 years), this added little to my experience of her work.

I didn’t know Margery’s story, so found her sections a little more interesting. A married mother of 14, she earned scorn for preaching, prophesying and weeping in public. Again and again, she was told to know her place and not dare to speak on behalf of God or question the clergy. She was a bold and passionate woman, and the accusations of heresy were no doubt motivated by a wish to see her humiliated for claiming spiritual authority. But nowadays, we would doubtless question her mental health – likewise for Julian when you learn that her shewings arose from a time of fevered hallucination. If you’re new to these figures, you might be captivated by their bizarre life stories and religious obsession, but I thought the bare telling was somewhat lacking in literary interest. (Read via NetGalley) [176 pages] ![]()

Coming out on January 19th from Bloomsbury.

Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken; Archipelago Books]

Ørstavik wrote this in the early months of 2020 while she was living in Milan with her husband, Luigi Spagnol, who was her Italian publisher as well as a painter. They had only been together for four years and he’d been ill for half of that. The average life expectancy for someone who had undergone his particular type of pancreatic cancer surgery was 15–20 months; “We’re at fifteen months now.” Indeed, Spagnol would die in June 2020. But Ørstavik writes from that delicate in-between time when the outcome is clear but hasn’t yet arrived:

Ørstavik wrote this in the early months of 2020 while she was living in Milan with her husband, Luigi Spagnol, who was her Italian publisher as well as a painter. They had only been together for four years and he’d been ill for half of that. The average life expectancy for someone who had undergone his particular type of pancreatic cancer surgery was 15–20 months; “We’re at fifteen months now.” Indeed, Spagnol would die in June 2020. But Ørstavik writes from that delicate in-between time when the outcome is clear but hasn’t yet arrived:

What’s real is that you’re still here, and at the same time, as if embedded in that, the fact that soon you’re going to die. Often I don’t feel a thing.

She knows, having heard it straight from his doctor’s lips, that her husband is going to die in a matter of months, but he doesn’t know. And now he wants to host a New Year’s Eve party, as is their annual tradition. Ørstavik skips between the present, the couple’s shared past, and an incident from her recent past that she hasn’t yet told anyone else: not long ago, while in Mexico for a literary festival, she fell in love with A., her handler. And while she hasn’t acted on that, beyond a kiss on the cheek, it’s smouldering inside her, a secret from the husband she still loves and can’t bear to hurt. Novels are where she can be most truthful, and she knows the one she needs to write will be healing.

There are many wrenching scenes and moments here, but it’s all delivered in a fairly flat style that left little impression on me. I wonder if I’d appreciate her fiction more. (Read via Edelweiss) [124 pages] ![]()

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

This was our January book club read. We’d had good luck with Gale before: his Notes from an Exhibition received our joint highest rating ever. As he’s often done in his fiction, he took inspiration from family history: here, the story of his great-grandfather Harry Cane, who emigrated to the Canadian prairies to farm in the most challenging of conditions. Because there is some uncertainty as to what precipitated his ancestor’s resettlement, Gale has chosen to imagine that Harry, though married and the father of a daughter, was in fact gay and left England to escape blackmailing and disgrace after his affair with a man was discovered.

This was our January book club read. We’d had good luck with Gale before: his Notes from an Exhibition received our joint highest rating ever. As he’s often done in his fiction, he took inspiration from family history: here, the story of his great-grandfather Harry Cane, who emigrated to the Canadian prairies to farm in the most challenging of conditions. Because there is some uncertainty as to what precipitated his ancestor’s resettlement, Gale has chosen to imagine that Harry, though married and the father of a daughter, was in fact gay and left England to escape blackmailing and disgrace after his affair with a man was discovered. A brief second review for Nordic FINDS. It’s the third time I’ve encountered some of these autofiction stories: this was a reread for me, and 13 of the pieces are also in Sculptor’s Daughter, which I skimmed from the library a few years ago. And yet I remembered nothing; not a single one was memorable. Most of the pieces are impressionistic first-person fragments of childhood, with family photographs interspersed. In later sections, the protagonist is an older woman, Jansson herself or a stand-in. I most enjoyed “Messages” and “Correspondence,” round-ups of bizarre comments and requests she received from readers. Of the proper stories, “The Iceberg” was the best. It’s a literal object the speaker alternately covets and fears, and no doubt a metaphor for much else. This one had the kind of profound lines Jansson slips into her children’s fiction: “Now I had to make up my mind. And that’s an awful thing to have to do” and “if one doesn’t dare to do something immediately, then one never does it.” A shame this wasn’t a patch on

A brief second review for Nordic FINDS. It’s the third time I’ve encountered some of these autofiction stories: this was a reread for me, and 13 of the pieces are also in Sculptor’s Daughter, which I skimmed from the library a few years ago. And yet I remembered nothing; not a single one was memorable. Most of the pieces are impressionistic first-person fragments of childhood, with family photographs interspersed. In later sections, the protagonist is an older woman, Jansson herself or a stand-in. I most enjoyed “Messages” and “Correspondence,” round-ups of bizarre comments and requests she received from readers. Of the proper stories, “The Iceberg” was the best. It’s a literal object the speaker alternately covets and fears, and no doubt a metaphor for much else. This one had the kind of profound lines Jansson slips into her children’s fiction: “Now I had to make up my mind. And that’s an awful thing to have to do” and “if one doesn’t dare to do something immediately, then one never does it.” A shame this wasn’t a patch on

Laila (Big Reading Life) and I attempted this as a buddy read, but we both gave up on it. I got as far as page 53 (in the 600+-page pocket paperback). The premise was alluring, with a magical white horse swooping in to rescue Peter Lake from a violent gang. I also appreciated the NYC immigration backstory, but not the adjective-heavy wordiness, the anachronistic exclamations (“Crap!” and “Outta my way, you crazy midget” – this is presumably set some time between the 1900s and 1920s) or the meandering plot. It was also disturbing to hear about Peter’s sex life when he was 12. From a Little Free Library (at Philadelphia airport) it came, and to a LFL (at the Bar Convent in York) it returned. Laila read a little further than me, enough to tell the library patron who recommended it to her that she’d given it a fair try.

Laila (Big Reading Life) and I attempted this as a buddy read, but we both gave up on it. I got as far as page 53 (in the 600+-page pocket paperback). The premise was alluring, with a magical white horse swooping in to rescue Peter Lake from a violent gang. I also appreciated the NYC immigration backstory, but not the adjective-heavy wordiness, the anachronistic exclamations (“Crap!” and “Outta my way, you crazy midget” – this is presumably set some time between the 1900s and 1920s) or the meandering plot. It was also disturbing to hear about Peter’s sex life when he was 12. From a Little Free Library (at Philadelphia airport) it came, and to a LFL (at the Bar Convent in York) it returned. Laila read a little further than me, enough to tell the library patron who recommended it to her that she’d given it a fair try. I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,

I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,  What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s

What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s  I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.

I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download)

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download) I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy)

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy) Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular  Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.”

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.” The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.”

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.” Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my

Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my  The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download)

The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download) The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy)

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy) I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.”

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.” A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief.

A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief. Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”.

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”. The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.”

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.” Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download)

Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download) Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy)

Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy) Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.”

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.” Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.” The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby. A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head. Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in