Open Water & Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year (#NovNov)

Open Water is our first buddy read, for Contemporary week of Novellas in November (#NovNov). Look out for the giveaway running on Cathy’s blog today!

I read this one back in April–May and didn’t get a chance to revisit it, but I’ll chime in with my brief thoughts recorded at the time. I then take a look back at 14 other novellas I’ve read this year; many of them I originally reviewed here. I also have several more contemporary novellas on the go to round up before the end of the month.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (2021)

[145 pages]

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

Ultimately, I wasn’t convinced that fiction was the right vehicle for this story, especially with all the references to other authors, from Hanif Abdurraqib to Zadie Smith (NW, in particular); I think a memoir with cultural criticism was what the author really intended. I’ll keep an eye out for Nelson, though – I wouldn’t be surprised if this makes it onto the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist in January. I feel like with his next book he might truly find his voice.

Readalikes:

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (also appears below)

- Poor by Caleb Femi (poetry with photographs)

- Normal People by Sally Rooney

Other reviews:

Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year:

(Post-1980; under 200 pages)

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

Assembly by Natasha Brown

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Blue Dog by Louis de Bernières

The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths

Tinkers by Paul Harding

An Island by Karen Jennings

Ness by Robert Macfarlane

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan

Broke City by Wendy McGrath

A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

In the Winter Dark by Tim Winton

Currently reading:

- Inside the Bone Box by Anthony Ferner

- My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

- The Cemetery in Barnes by Gabriel Josipovici

What novellas do you have underway this month? Have you read any of my selections?

Love Your Library Begins: October 2021

It’s the opening month of my new Love Your Library meme! I hope some of you will join me in writing about the libraries you use and what you’ve borrowed from them recently. I plan to treat these monthly posts as a sort of miscellany.

Although I likely won’t do thorough Library Checkout rundowns anymore, I’ll show photos of what I’ve borrowed, give links to reviews of a few recent reads, and then feature something random, such as a reading theme or library policy or display.

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’m co-opting a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

Recently borrowed

Stand-out reads

The Echo Chamber by John Boyne

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

What is Boyne spoofing here? Mostly smartphone addiction, but also cancel culture. I imagined George as Hugh Bonneville throughout; indeed, the novel would lend itself very well to screen adaptation. And I loved how Beverley’s new ghostwriter, never given any name beyond “the ghost,” feels like the most real and perceptive character of all. Surely one of the funniest books I will read this year. (Full review).

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

Through their relationships with Felix (a rough-around-the-edges warehouse worker) and Simon (slightly older and involved in politics), Rooney explores the question of whether lasting bonds can be formed despite perceived differences of class and intelligence. The background of Alice’s nervous breakdown and Simon’s Catholicism also bring in sensitive treatments of mental illness and faith. (Full review).

This month’s feature

I spotted a few of these during my volunteer shelving and then sought out a couple more. All five are picture books composed by authors not known for their writing for children.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

Booker Prize 2021: Longlist Reading and Shortlist Predictions

The 2021 Booker Prize shortlist will be announced tomorrow, September 14th, at 4 p.m. via a livestream. I’ve managed to read or skim eight of 13 from the longlist, only one of which I sought out specifically after it was nominated (An Island – the one no one had heard of; it turns out it was released by a publisher based just 1.5 miles from my home!). I review my four most recent reads below, followed by excerpts of reviews of ones I read a while ago and my brief thoughts on the rest, including what I expect to see on tomorrow’s shortlist.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Klara is an Artificial Friend purchased as part of an effort to combat the epidemic of teenage loneliness – specifically, to cheer up her owner, Josie, who suffers from an unspecified illness and is in love with her neighbour, Rick, a bright boy who remains excluded. Klara thinks of the sun as a god, praying to it and eventually making a costly bargain to try to secure Josie’s future health.

Part One’s 45 pages are slow and tedious; the backstory could have been dispensed with in five fairy tale-like pages. There’s a YA air to the story: for much of the length I might have been rereading Everything, Everything. In fact, when I saw Ishiguro introduce the novel at a Guardian/Faber launch event, he revealed that it arose from a story he wrote for children. The further I got, the more I was sure I’d read it all before. That’s because the plot is pretty much identical to the final story in Mary South’s You Will Never Be Forgotten.

Klara’s highly precise diction, referring to everyone in the third person, also gives this the feeling of translated fiction. While that is part of Ishiguro’s aim, of course – to explore the necessarily limited perspective and speech of a nonhuman entity (“Her ability to absorb and blend everything she sees around her is quite amazing”) – it makes the prose dull and belaboured. The secondary characters include various campy villains, the ‘big reveals’ aren’t worth waiting for, and the ending is laughably reminiscent of Toy Story. This took me months and months to force myself through. What a slog! (New purchase)

An Island by Karen Jennings (2019)

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Although the core action takes place in just four days, Samuel is so mentally shaky that his memories start getting mixed up with real life. We learn that he has been a father, a prisoner and a beggar. Jennings is South African, and in this parallel Africa, racial hierarchy still holds sway and a general became a dictator through a military coup. Samuel’s father was involved in the independence movement, while Samuel himself was arrested for resisting the dictator.

The novella’s themes – jealousy, mistrust, possessiveness, suspicion, and a return to primitive violence – are of perennial relevance. Somehow, it didn’t particularly resonate for me. It’s not dissimilar in style to J. M. Coetzee’s vague but brutal detachment, and it’s a highly male vision à la Doggerland. Though highly readable, it’s ultimately a somewhat thin fable with a predictable message about xenophobia. Still, I’m glad I discovered it through the Booker longlist.

My thanks to Holland House for the free copy for review.

Bewilderment by Richard Powers

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Three brides for three brothers: as Laura notes, it sounds like the setup of a folk tale, and there’s a timeless feel to this short novel set in the Punjab in the late 1920s and 1990s – it also reminded me of biblical stories like those of Jacob and Leah and David and Bathsheba. Mehar is one of three teenage girls married off to a set of brothers. The twist is that, because they wear heavy veils and only meet with their husbands at night for procreation, they don’t know which is which. Mehar is sure she’s worked out which brother is her husband, but her well-meaning curiosity has lasting consequences.

In the later storyline, a teenage addict returns from England to his ancestral estate to try to get clean before going to university and becomes captivated by the story of his great-grandmother and her sister wives, who were confined to the china room. The characters are real enough to touch, and the period and place details make the setting vivid. The two threads both explore limitations and desire, and the way the historical narrative keeps surging back in makes things surprisingly taut. See also Susan’s review. (Read via NetGalley)

Other reads, in brief:

(Links to my full reviews)

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

Here’s what I expect to still be in the running after tomorrow. Clear-eyed, profound, international; bridging historical and contemporary; much that’s unabashedly highbrow.

- Second Place by Rachel Cusk

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Bewilderment by Richard Powers

- China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

- Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

What have you read from the longlist? What do you expect to be shortlisted?

20 Books of Summer, #18–19: The Other’s Gold and Black Dogs

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a novel about a quartet of college friends and the mistakes that mar their lives and a novella about the enduring impact of war set just after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames (2019)

Make new friends but keep the old,

One is silver and the other’s gold.

Do you know that little tune? We would sing it as a round at summer camp. It provides a clever title for this story of four college roommates whose lives are marked by the threat of sexual violence and ambivalent feelings about motherhood. Alice, Ji Sun, Lainey and Margaret first meet as freshmen in 2002 when they’re assigned to the same suite (with a window seat! how envious am I?) at Quincy-Hawthorn College.

They live together for the whole four years – a highly unusual situation – and see each other through crises at college and in the years to come as they find partners and meander into motherhood. Iraq War protests and the Occupy movement form a turbulent background, but the friends’ overriding concerns are more personal. One girl was molested by her brother as a child and has kept secret her act of revenge; one has a crush on a professor until she learns he has sexual harassment charges being filed against him by multiple female students. Infertility later provokes jealousy between the young women, and mental health issues come to the fore.

They live together for the whole four years – a highly unusual situation – and see each other through crises at college and in the years to come as they find partners and meander into motherhood. Iraq War protests and the Occupy movement form a turbulent background, but the friends’ overriding concerns are more personal. One girl was molested by her brother as a child and has kept secret her act of revenge; one has a crush on a professor until she learns he has sexual harassment charges being filed against him by multiple female students. Infertility later provokes jealousy between the young women, and mental health issues come to the fore.

As in Expectation by Anna Hope, the book starts to be all about babies at a certain point. That’s not a problem if you’re prepared for and interested in this theme, but I love campus novels so much that my engagement waned as the characters left university behind. Also, the characters seemed too artificially manufactured to inject diversity (Ji Sun is a wealthy Korean; adopted Lainey is of mixed Latina heritage, and bisexual; Margaret has Native American blood) and embody certain experiences. And, unfortunately, any #MeToo-themed read encountered in the wake of My Dark Vanessa is going to pale by comparison.

Part One held my interest, but after that I skimmed to the end. Ideally, I would have chosen replacements and not included skims like this and Green Mansions, but it’s not the first summer that I’ve had to count DNFs and skimmed books – my time and attention are always being diverted by paid review work, review copies and library books with imminent deadlines. I’ve read lots of fiction about groups of female friends this summer, partly by accident and partly by design, and will likely do a feature on it in an upcoming month. For now, I’d recommend Lara Feigel’s The Group instead of this.

With thanks to Pushkin Press (ONE imprint) for the free e-copy for review.

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan (1992)

When I read the blurb, I worried I’d read this before and forgotten it: all it mentions is a young couple setting off on honeymoon and having an encounter with evil. Isn’t that the plot of The Comfort of Strangers? I thought. In fact, this only happens to have the vacation detail in common, and has a very different setup and theme overall.

When I read the blurb, I worried I’d read this before and forgotten it: all it mentions is a young couple setting off on honeymoon and having an encounter with evil. Isn’t that the plot of The Comfort of Strangers? I thought. In fact, this only happens to have the vacation detail in common, and has a very different setup and theme overall.

Jeremy lost his parents in a car accident (my least favourite fictional trope – far too convenient a way of setting a character off on their own!) when he was eight years old, and is self-aware enough to realize that he has been seeking for parental figures ever after. He becomes deeply immersed in the story of his wife’s parents, Bernard and June, even embarking on writing a memoir based on what June, from her nursing home bed, tells him of their early life (Part One).

After June’s death, Jeremy takes Bernard to Berlin (Part Two) to soak up the atmosphere just after the Wall comes down, but the elderly man is kicked by a skinhead. The other key thing that happens on this trip is that he refutes June’s account of their honeymoon. At June’s old house in France (Part Three), Jeremy feels her presence and seems to hear the couple’s voices. Only in Part Four do we learn what happened on their 1946 honeymoon trip to France: an encounter with literal black dogs that also has a metaphorical dimension, bringing back the horrors of World War II.

I think the novel is also meant to contrast Communist ideals – Bernard and June were members of the Party in their youth – with how Communism has played out in history. It was shortlisted for the Booker, which made me feel that I must be missing something. A fairly interesting read, most similar in his oeuvre (at least of the 15 I’ve read so far) to The Child in Time. (Secondhand purchase from a now-defunct Newbury charity shop)

Coming up next: The latest book by John Green – it’s due back at the library on the 31st so I’ll aim to review it before then, possibly with a rainbow-covered novel as a bonus read.

First Four in a Row: Márai, Maupin, McEwan, McKay

I announced a few new TBR reading projects back in May 2020, including a Four in a Row Challenge (see the ‘rules’, such as they are, in my opening post). It only took me, um, nearly 11 months to complete a first set! The problem was that I kept changing my mind on which four to include and acquiring more that technically should go into the sequence, e.g. McCracken, McGregor; also, I stalled on the Maupin for ages. But here we are at last. Debbie, meanwhile, took up the challenge and ran with it, completing a set of four novels – also by M authors, clearly a numerous and tempting bunch – back in October. Here’s hers.

I’m on my way to completing a few more sets: I’ve read one G, one and a bit H, and I selected a group of four L. I’ve not chosen a nonfiction quartet yet, but that could be an interesting exercise: I file by author surname even within categories like science/nature and travel, so this could throw up interesting combinations of topics. Do feel free to join in this challenge if, like me, you could use a push to get through more of the books on your shelves.

Embers by Sándor Márai (1942)

[Translated from the Hungarian by Carol Brown Janeway]

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

Henrik was 10 when he met Konrad at an academy school. They were soon the best of friends, but two things came between them: first was the difference in their backgrounds (“each forgave the other’s original sin: wealth on the one hand and poverty on the other”); second was their love for the same woman.

I appreciated the different setup to this one – a male friendship, just a few very old characters, the probing of the past through memory and dialogue – but it was so languid that I struggled to stay engaged with the plot.

*My next will be Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, another charity shop find.

Favourite lines:

“My homeland was a feeling, and that feeling was mortally wounded.”

“Life becomes bearable only when one has come to terms with who one is, both in one’s own eyes and in the eyes of the world.”

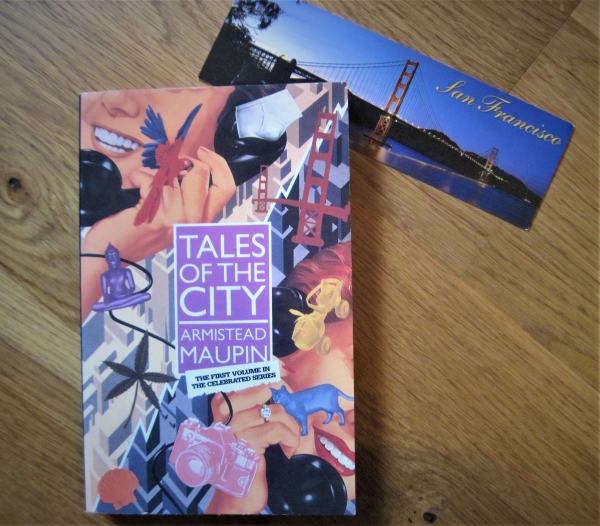

Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (1978)

I’d picked this up from the free bookshop we used to have in the local mall (the source of my next two as well) and started it during Lockdown #1 because in The Novel Cure it is given as a prescription for Loneliness. Berthoud and Elderkin suggest it can make you feel like part of a gang of old friends, and it’s “as close to watching television as literature gets” due to the episodic format – the first four Tales books were serialized in the San Francisco Chronicle.

How I love a perfect book and bookmark combination!

The titled chapters are each about three pages long, which made it an ideal bedside book – I would read a chapter per night before sleep. The issue with this piecemeal reading strategy, though, was that I never got to know any of the characters; because I’d often only pick up the book once a week or so, I forgot who people were and what was going on. That didn’t stop individual vignettes from being entertaining, but meant it didn’t all come together for me.

Maupin opens on Mary Ann Singleton, a 25-year-old secretary who goes to San Francisco on vacation and impulsively decides to stay. She rooms at Anna Madrigal’s place on Barbary Lane and meets a kooky assortment of folks, many of them gay – including her new best friend, Michael Tolliver, aka “Mouse.” There are parties and affairs, a pregnancy and a death, all told with a light touch and a clear love for the characters; dialogue predominates. While it’s very much of its time, it manages not to feel too dated overall. I can see why many have taken the series to heart, but don’t think I’ll go further with Maupin’s work.

Note: Long before I tried the book, I knew about it through one of my favourite Bookshop Band songs, “Cleveland,” which picks up on Mary Ann’s sense of displacement as she ponders whether she’d be better off back in Ohio after all. Selected lyrics:

Quaaludes and cocktails

A story book lane

A girl with three names

A place, post-Watergate

Freed from its bird cage

Where the unafraid parade

[…]

Perhaps, we should all

Go back to Cleveland

Where we know what’s around the bend

[…]

Citizens of Atlantis

The Madrigal Enchantress cries

And we decide, to stay and bide our time

On this far-out, far-flung peninsula.

The Children Act by Ian McEwan (2014)

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW]

She rules that the doctors should go ahead with the treatment. “He must be protected from his religion and from himself.” Adam, now better but adrift from the religion he was raised in, starts stalking Fiona and sending her letters and poems. Estranged from her husband, who wants her to condone his affair with a young colleague, and fond of Adam, Fiona spontaneously kisses the young man while traveling for work near Newcastle. But thereafter she ignores his communications, and when he doesn’t seek treatment for his recurring cancer and dies, she blames herself.

[END OF SPOILERS]

It’s worth noting that the AI in McEwan’s most recent full-length novel, Machines Like Me, is also named Adam, and in both books there’s uncertainty about whether the Adam character is supposed to be a child substitute.

The Birth House by Ami McKay (2006)

Dora is the only daughter to be born into the Rare family of Nova Scotia’s Scots Bay in five generations. At age 17, she becomes an apprentice to Marie Babineau, a Cajun midwife and healer who relies on ancient wisdom and appeals to the Virgin Mary to keep women safe and grant them what they want, whether that’s a baby or a miscarriage. As the 1910s advance and the men of the village start leaving for the war, the old ways represented by Miss B. and Dora come to be seen as a threat. Dr. Thomas wants women to take out motherhood insurance and commit to delivering their babies at the new Canning Maternity Home with the help of chloroform and forceps. “Why should you ladies continue to suffer, most notably the trials of childbirth, when there are safe, modern alternatives available to you?” he asks.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

There are a few places where the narrative is almost overwhelmed by all the (admittedly, fascinating) facts McKay, a debut author, turned up in her research, and where the science versus superstition dichotomy seems too simplistic, but for the most part this was just the sort of absorbing, atmospheric historical fiction that I like best. McKay took inspiration from her own home, an old birthing house in the Bay of Fundy.

Book Serendipity in the Final Months of 2020

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. (Earlier incidents from the year are here, here, and here.)

- Eel fishing plays a role in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson.

- A girl’s body is found in a canal in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and Carrying Fire and Water by Deirdre Shanahan.

- Curlews on covers by Angela Harding on two of the most anticipated nature books of the year, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn (and both came out on September 3rd).

- Thanksgiving dinner scenes feature in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid.

- A gay couple has the one man’s mother temporarily staying on the couch in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Memorial by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading two “The Gospel of…” titles at once, The Gospel of Eve by Rachel Mann and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson (and I’d read a third earlier in the year, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving).

- References to Dickens’s David Copperfield in The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan.

- The main female character has three ex-husbands, and there’s mention of chin-tightening exercises, in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer.

- A Welsh hills setting in On the Red Hill by Mike Parker and Along Came a Llama by Ruth Janette Ruck.

- Rachel Carson and Silent Spring are mentioned in A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee, The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson. SS was also an influence on Losing Eden by Lucy Jones, which I read earlier in the year.

- There’s nude posing for a painter or photographer in The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel, How to Be Both by Ali Smith, and Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- A weird, watery landscape is the setting for The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

- Bawdy flirting between a customer and a butcher in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Just Like You by Nick Hornby.

- Corbels (an architectural term) mentioned in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver.

- Near or actual drownings (something I encounter FAR more often in fiction than in real life, just like both parents dying in a car crash) in The Idea of Perfection, The Glass Hotel, The Gospel of Eve, Wakenhyrst, and Love and Other Thought Experiments.

- Nematodes are mentioned in The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A toxic lake features in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook and Real Life by Brandon Taylor (both were also on the Booker Prize shortlist).

- A black scientist from Alabama is the main character in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- Graduate studies in science at the University of Wisconsin, and rivals sabotaging experiments, in Artifact by Arlene Heyman and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A female scientist who experiments on rodents in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Artifact by Arlene Heyman.

- There are poems about blackberrying in Dearly by Margaret Atwood, Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols, and How to wear a skin by Louisa Adjoa Parker. (Nichols’s “Blackberrying Black Woman” actually opens with “Everyone has a blackberry poem. Why not this?” – !)

This is not about

This is not about

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes was the other book I popped in the back of my purse for yesterday’s London outing. Barnes is one of my favourite authors – I’ve read 21 books by him now! – but I remember not being very taken with this Booker winner when I read it just over 10 years ago. (I prefer to think of his win as being for his whole body of work as he’s written vastly more original and interesting books, like

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes was the other book I popped in the back of my purse for yesterday’s London outing. Barnes is one of my favourite authors – I’ve read 21 books by him now! – but I remember not being very taken with this Booker winner when I read it just over 10 years ago. (I prefer to think of his win as being for his whole body of work as he’s written vastly more original and interesting books, like  The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark was January’s book club selection. I had remembered no details apart from the title character being a teacher. It’s a between-the-wars story set in Edinburgh. Miss Brodie’s pet students are girls with attributes that remind her of aspects of herself. Our group was appalled at what we today would consider inappropriate grooming, and at Miss Brodie’s admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. Educational theory was interesting to think about, however. Spark’s work is a little astringent for me, and I also found this one annoyingly repetitive on the sentence level. (Public library)

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark was January’s book club selection. I had remembered no details apart from the title character being a teacher. It’s a between-the-wars story set in Edinburgh. Miss Brodie’s pet students are girls with attributes that remind her of aspects of herself. Our group was appalled at what we today would consider inappropriate grooming, and at Miss Brodie’s admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. Educational theory was interesting to think about, however. Spark’s work is a little astringent for me, and I also found this one annoyingly repetitive on the sentence level. (Public library)

Brit-Think, Ameri-Think: A Transatlantic Survival Guide by Jane Walmsley: This is the revised edition from 2003, so I must have bought it as preparatory reading for my study abroad year in England. This may even be the third time I’ve read it. Walmsley, an American in the UK, compares Yanks and Brits on topics like business, love and sex, parenting, food, television, etc. I found my favourite lines again (in a panel entitled “Eating in Britain: Things that Confuse American Tourists”): “Why do Brits like snacks that combine two starches? (a) If you’ve got spaghetti, do you really need the toast? (b) What’s a ‘chip-butty’? Is it fatal?” The explanation of the divergent sense of humour is still spot on, and I like the Gray Jolliffe cartoons. Unfortunately, a lot of the rest feels dated – she’d updated it to 2003’s pop culture references, but these haven’t aged well. (New purchase?)

Brit-Think, Ameri-Think: A Transatlantic Survival Guide by Jane Walmsley: This is the revised edition from 2003, so I must have bought it as preparatory reading for my study abroad year in England. This may even be the third time I’ve read it. Walmsley, an American in the UK, compares Yanks and Brits on topics like business, love and sex, parenting, food, television, etc. I found my favourite lines again (in a panel entitled “Eating in Britain: Things that Confuse American Tourists”): “Why do Brits like snacks that combine two starches? (a) If you’ve got spaghetti, do you really need the toast? (b) What’s a ‘chip-butty’? Is it fatal?” The explanation of the divergent sense of humour is still spot on, and I like the Gray Jolliffe cartoons. Unfortunately, a lot of the rest feels dated – she’d updated it to 2003’s pop culture references, but these haven’t aged well. (New purchase?)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read ( In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.  Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.

Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.  February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

My third by Adichie this year, and an ideal follow-up to

My third by Adichie this year, and an ideal follow-up to  “Why do people travel? … I suppose to lose part of themselves. Parts which trap us. Or maybe because it is possible, and it helps us believe there is a future.”

“Why do people travel? … I suppose to lose part of themselves. Parts which trap us. Or maybe because it is possible, and it helps us believe there is a future.” Who could resist such a title and cover?! Unfortunately, I didn’t warm to Eisenberg’s writing and got little out of these stories, especially “Merge,” the longest and only one of the six that hadn’t previously appeared in print. The title implies collective responsibility and is applied to a story of artists on a retreat in Europe. “The Third Tower” has a mental hospital setting. In “Recalculating,” a character only learns about an estranged uncle after his death. The two I liked most were “Taj Mahal,” about competing views of a filmmaker from the golden days of Hollywood, and “Cross Off and Move On,” about a family’s Holocaust history. But all are very murky in my head. (See Susan’s more positive

Who could resist such a title and cover?! Unfortunately, I didn’t warm to Eisenberg’s writing and got little out of these stories, especially “Merge,” the longest and only one of the six that hadn’t previously appeared in print. The title implies collective responsibility and is applied to a story of artists on a retreat in Europe. “The Third Tower” has a mental hospital setting. In “Recalculating,” a character only learns about an estranged uncle after his death. The two I liked most were “Taj Mahal,” about competing views of a filmmaker from the golden days of Hollywood, and “Cross Off and Move On,” about a family’s Holocaust history. But all are very murky in my head. (See Susan’s more positive  Last year I loved reading Mantel’s collection

Last year I loved reading Mantel’s collection  There’s a nastiness to these early McEwan stories that reminded me of Never Mind by Edward St. Aubyn. The teenage narrator of “Homemade” tells you right in the first paragraph that his will be a tale of incest. A little girl’s body is found in the canal in “Butterflies.” The voice in “Conversation with a Cupboard Man” is that of someone who has retreated into solitude after being treated cruelly at the workplace (“I hate going outside. I prefer it in my cupboard”). “Last Day of Summer” seems like a lovely story about a lodger being accepted as a member of the family … until the horrific last page. Only “Cocker at the Theatre” was pure comedy, of the raunchy variety (emphasis on “cock”). You get the sense of a talented writer whose mind you really wouldn’t want to spend time in; had this been my first exposure to McEwan, I would probably never have opened up another of his books. [Public library]

There’s a nastiness to these early McEwan stories that reminded me of Never Mind by Edward St. Aubyn. The teenage narrator of “Homemade” tells you right in the first paragraph that his will be a tale of incest. A little girl’s body is found in the canal in “Butterflies.” The voice in “Conversation with a Cupboard Man” is that of someone who has retreated into solitude after being treated cruelly at the workplace (“I hate going outside. I prefer it in my cupboard”). “Last Day of Summer” seems like a lovely story about a lodger being accepted as a member of the family … until the horrific last page. Only “Cocker at the Theatre” was pure comedy, of the raunchy variety (emphasis on “cock”). You get the sense of a talented writer whose mind you really wouldn’t want to spend time in; had this been my first exposure to McEwan, I would probably never have opened up another of his books. [Public library]