A Quick Look Back at Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell for #LiteraryWives

I read Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize winner, Hamnet, at its release in 2020. Unfortunately, it has been my least favourite of her novels (I’ve read all but My Lover’s Lover now), and it turns out 3.5 years is too soon to reread and appreciate anew. But I had a quick skim back through, this time focusing on the central marriage and the question we ask for the Literary Wives online book club:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

From my original review: O’Farrell imagines the context of the death of William Shakespeare’s son Hamnet and the effect it had on the playwright’s work – including, four years later, Hamlet. Curiously, she has decided never to mention Shakespeare by name in her novel, so he remains a passive, shadowy figure seen only in relation to his wife and children – he’s referred to as “the father,” “the Latin tutor” or “her husband.” Instead, the key characters are his wife, Agnes (most will know her as Anne, but Agnes was the name her father, Richard Hathaway, used for her in his will), and Hamnet himself.

It is refreshing, especially for the time period, to have the wife’s experience and perspective be primary, and the husband in the background to the extent of being unnamed. Both, however, blame themselves for not being there when 11-year-old Hamnet fell ill with what O’Farrell posits was the Plague. Shakespeare was away in London with his theatre company; Agnes was off tending her bees. Shakespeare is only present in flashbacks – in which he morphs from eager tutor to melancholy drinker – until three-quarters of the way through the novel, when he returns to Stratford, too late. All he can do then is carry his son’s corpse.

I have heard it said many times that few marriages survive the death of a child. And for a while that looks like it will be the case here, too:

Her husband takes her arm as they reach the gate; she turns to look at him and it is as if she has never seen him before, so odd and distorted and old do his features seem. Is it their long separation, is it grief, is it all the tears? she wonders, as she regards him. Who is this person next to her, claiming her arm, holding it to him?

How were they to know that Hamnet was the pin holding them together? That without him they would all fragment and fall apart, like a cup shattered on the floor?

With his earnings, Shakespeare buys the family a new house, but never moves them to London as he once intended. He continues to stay away for long periods at a time, leaving Agnes to her grief. When, four years after Hamnet’s death, Agnes and their daughters learn that he has written a play about a character called Hamlet, they feel betrayed, but Agnes goes to a performance and her anger melts as she recognizes her son. “It is him. It is not him. … grown into a near-man, as he would be now, had he lived, on the stage, walking with her son’s gait, talking in her son’s voice, speaking words written for him by her son’s father.”

Although O’Farrell leaves it there, creating uncertainty about the couple’s future, she implies that the play has been the saving of both of them. For Shakespeare, it was the outlet for his grief. For Agnes, it was the proof she needed that he loved their son, grieved him as bitterly as she did, and still remembers him. That seems to be enough to hold them together.

While her next novel, The Marriage Portrait, which I liked a lot more as historical fiction goes, might seem on the surface better suited for this club, Hamnet was in fact perfect for the prompt, revealing an aspect I don’t recall looking at before: the strain that a child’s illness and death can place on a marriage. At my first reading I found the prose flat and detached, to the point of vagueness, and thought there was anachronistic language and unsubtle insertion of research. This time, I was more aware of how the deliberate evenness softens the emotion, making it more bearable – though, still, I have a friend who gave up reading this partway because she found it too raw.

See also Kay’s and Naomi’s responses!

The next book, for March 2024, will be Mrs. March by Virginia Feito.

Book Serendipity, Mid-April through Early June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Fishing with dynamite takes place in Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- Egg collecting (illegal!) is observed and/or discussed in Sea Bean by Sally Huband and The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth.

- Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know is quoted in What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma and Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler. I then bought a secondhand copy of the Levy on my recent trip to the States.

- “Piss-en-lit” and other folk names for dandelions are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

- Buttercups and nettles are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (and other members of the Ranunculus family, which includes buttercups, in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught).

- The speaker’s heart is metaphorically described as green in a poem in Lo by Melissa Crowe and The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly.

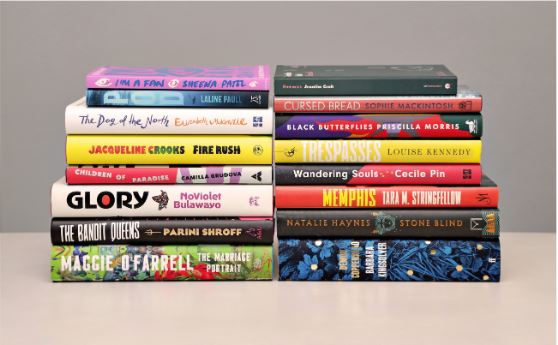

- Discussion of how an algorithm can know everything about you in Tomb Sweeping by Alexandra Chang and I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel.

- A brother drowns in The Loved Ones: Essays to Bury the Dead by Madison Davis, What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

A few cases of a book recalling a specific detail from an earlier read:

- This metaphor in The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry links it to The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell, another work of historical fiction I’d read not long before: “He has further misgivings about the scalloped gilt bedside table, which wouldn’t look of place in the palazzo of an Italian poisoner.”

- This reference in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton links it back to Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon (could it be the specific book she had in mind? I suspect it was out of print in 1989, so it’s more likely it was Elizabeth Mavor’s 1971 biography The Ladies of Llangollen): “Do you have a book about those ladies, the eighteenth-century ones, who lived together in some remote place, but everyone knew them?”

- This metaphor in Things My Mother Never Told Me by Blake Morrison links it to The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry: “Moochingly revisiting old places, I felt like Thomas Hardy in mourning for his wife.”

- A Black family is hounded out of a majority-white area by harassment in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- A scene of eating a deceased relative’s ashes in 19 Claws and a Black Bird by Agustina Bazterrica and The Loved Ones by Madison Davis.

- A girl lives with her flibbertigibbet mother and stern grandmother in “Wife Days,” one story from How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery.

- Macramé is mentioned in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain.

- A fascination with fractals in Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal and one story in Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain. They are also mentioned in one essay in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- I found disappointed mentions of the fact that characters wear blackface in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town on the Prairie in Monsters by Claire Dederer and, the very next day, Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Moon jellyfish are mentioned in the Blood and Cord anthology edited by Abi Curtis, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sea Bean by Sally Huband.

- A Black author is grateful to their mother for preparing them for life in a white world in the memoirs-in-essays I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- The children’s book The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson is mentioned in The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- The protagonist’s father brings home a tiger as a pet/object of display in The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell and The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller.

- Bloor Street, Toronto is mentioned in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thinking about the stars is quoted in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- Wondering whether a marine animal would be better off in captivity, where it could live much longer, in The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller (an octopus) and Sea Bean by Sally Huband (porpoises).

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

- Characters named June in “Indigo Run,” the novella-length story in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail.

- “Explicate!” is a catchphrase uttered by a particular character in Girls They Write Songs About by Carlene Bauer and The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller.

- It’s mentioned that people used to get dressed up for going on airplanes in Fly Girl by Ann Hood and The Lights by Ben Lerner.

- Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is a setting in The Lights by Ben Lerner and Grave by Allison C. Meier.

- Last year I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, in which Oregon Trail re-enactors (in a video game) die of dysentery; this is also a live-action plot point in “Pioneers,” one story in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow.

- A bunch (4 or 5) of Italian American sisters in Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon and Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

20 Books of Summer, 1–3: Hargrave, Powles & Stewart

Plants mirror minds,

Healing, harming powers

Growing green thoughts.

(First stanza of “Plants Mirror Minds” from The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws)

Here are my first three selections for my flora-themed summer reading. I hope to get through more of my own books, as opposed to library books and review copies, as the months go on. Today I have one of each from fiction, nonfiction and poetry, with the settings ranging from 16th-century Alsace to late-20th-century Spain.

The Dance Tree by Kiran Millwood Hargrave (2022)

Kiran Millwood Hargrave is one of my favourite new voices in historical fiction (she had written fiction for children and young adults before 2020’s The Mercies). Both novels hit the absolute sweet spot between the literary and women’s fiction camps, choosing a lesser-known time period and incident and filling in the background with sumptuous detail and language. Both also consider situations in which women, queer people and other cultural minorities were oppressed, and imagine characters pushing against those boundaries in affirming but authentic-feeling ways.

Kiran Millwood Hargrave is one of my favourite new voices in historical fiction (she had written fiction for children and young adults before 2020’s The Mercies). Both novels hit the absolute sweet spot between the literary and women’s fiction camps, choosing a lesser-known time period and incident and filling in the background with sumptuous detail and language. Both also consider situations in which women, queer people and other cultural minorities were oppressed, and imagine characters pushing against those boundaries in affirming but authentic-feeling ways.

The setting is Strasbourg in the sweltering summer of 1518, when a dancing plague (choreomania) hit and hundreds of women engaged in frenzied public dancing, often until their feet bled or even, allegedly, until 15 per day dropped dead. Lisbet observes this all at close hand through her sister-in-law and best friend, who get caught up in the dancing. In the final trimester of pregnancy at last after the loss of many pregnancies and babies, Lisbet tends to the family beekeeping enterprise while her husband is away, but gets distracted when two musicians (brought in to accompany the dancers; an early strategy before the council cracked down), one a Turk, lodge with her and her mother-in-law. The dance tree, where she commemorates her lost children, is her refuge away from the chaos enveloping the city. She’s a naive point-of-view character who quickly has her eyes opened about different ways of living. “It takes courage, to love beyond what others deem the right boundaries.”

This is likely to attract readers of Hamnet; I was also reminded of The Sleeping Beauties, in that the author’s note discusses the possibility that the dancing plagues were an example of a mass hysteria that arose in response to religious restrictions. (Public library) ![]()

Magnolia by Nina Mingya Powles (2020)

(Powles also kicked off my 2020 food-themed summer reading.) This came out from Nine Arches Press and a small New Zealand press two years ago but is being published in the USA by Tin House in August. I’ve reviewed it for Shelf Awareness in advance of that release. Those who are new to Powles’s work should enjoy her trademark blend of themes in this poetry collection. She’s mixed race and writes about crossing cultural and language boundaries – especially trying to express herself in Chinese and Hakka. Often, food is her way of embodying split loyalties and love for her heritage. I noted the alliteration in “Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly opening under swirls of soy sauce.” Magnolia is the literal translation of “Mulan,” and that Disney movie and a few other films play a major role here, as do writers Eileen Chang and Robin Hyde. My issue with the book is that it doesn’t feel sufficiently different from her essay collections that I’ve read – the other is Small Bodies of Water – especially given that many of the poems are in prose paragraphs. [Update: I dug out my copy of Small Bodies of Water from a box and found that, indeed, one piece had felt awfully familiar for a reason: that book contains a revised version of “Falling City” (about Eileen Chang’s Shanghai apartment), which first appeared here.] (Read via Edelweiss)

(Powles also kicked off my 2020 food-themed summer reading.) This came out from Nine Arches Press and a small New Zealand press two years ago but is being published in the USA by Tin House in August. I’ve reviewed it for Shelf Awareness in advance of that release. Those who are new to Powles’s work should enjoy her trademark blend of themes in this poetry collection. She’s mixed race and writes about crossing cultural and language boundaries – especially trying to express herself in Chinese and Hakka. Often, food is her way of embodying split loyalties and love for her heritage. I noted the alliteration in “Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly opening under swirls of soy sauce.” Magnolia is the literal translation of “Mulan,” and that Disney movie and a few other films play a major role here, as do writers Eileen Chang and Robin Hyde. My issue with the book is that it doesn’t feel sufficiently different from her essay collections that I’ve read – the other is Small Bodies of Water – especially given that many of the poems are in prose paragraphs. [Update: I dug out my copy of Small Bodies of Water from a box and found that, indeed, one piece had felt awfully familiar for a reason: that book contains a revised version of “Falling City” (about Eileen Chang’s Shanghai apartment), which first appeared here.] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree by Chris Stewart (2002)

It’s at least 10 years ago, probably nearer 15, that I read Driving over Lemons, the first in Stewart’s eventual trilogy about buying a remote farm in Andalusia. His books are in the Peter Mayle vein, low-key and humorous: an Englishman finds the good life abroad and tells amusing anecdotes about the locals and his own mishaps.

It’s at least 10 years ago, probably nearer 15, that I read Driving over Lemons, the first in Stewart’s eventual trilogy about buying a remote farm in Andalusia. His books are in the Peter Mayle vein, low-key and humorous: an Englishman finds the good life abroad and tells amusing anecdotes about the locals and his own mishaps.

This sequel stood out for me a little more than the previous book, if only because I mostly read it in Spain. It’s in discrete essays, some of which look back on his earlier life. He was a founding member of Genesis and very briefly the band’s drummer; and to make some cash for the farm he used to rent himself out as a sheep shearer, including during winters in Sweden.

To start with, they were really very isolated, such that getting a telephone line put in revolutionized their lives. By this time, his first book had become something of a literary sensation, so he reflects on its composition and early reception, remembering when the Mail sent a clueless reporter out to find him. Spanish bureaucracy becomes a key element, especially when it looks like their land might be flooded by the building of a dam. Despite that vague sense of dread, this was good fun. (Public library) ![]()

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”. In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,  Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Golden Boys by Phil Stamper: Four gay high school students in small-town Ohio look forward to a summer of separate travels for jobs and internships and hope their friendships will stay the course. With alternating first-person passages and conversation threads, this YA novel is proving to be a sweet, fun page turner and the perfect follow-up to the Heartstopper series (my summer crush from last year).

Golden Boys by Phil Stamper: Four gay high school students in small-town Ohio look forward to a summer of separate travels for jobs and internships and hope their friendships will stay the course. With alternating first-person passages and conversation threads, this YA novel is proving to be a sweet, fun page turner and the perfect follow-up to the Heartstopper series (my summer crush from last year). Summer by Edith Wharton: An adopted young woman (and half-hearted librarian) named Charity Royall gets a shot at romance when a stranger arrives in her New England town. I’m only 30 pages in so far, but this promises to be a great read – but please not as tragic as Ethan Frome? (Apparently, Wharton called it a favourite among her works, and referred to it as “the Hot Ethan,” which I’m going to guess she meant thermally.)

Summer by Edith Wharton: An adopted young woman (and half-hearted librarian) named Charity Royall gets a shot at romance when a stranger arrives in her New England town. I’m only 30 pages in so far, but this promises to be a great read – but please not as tragic as Ethan Frome? (Apparently, Wharton called it a favourite among her works, and referred to it as “the Hot Ethan,” which I’m going to guess she meant thermally.)

Or try the American summer of 1975 instead, with

Or try the American summer of 1975 instead, with

Mustique Island by Sarah McCoy: “A sun-splashed romp with a rich divorcée and her two wayward daughters in 1970s Mustique, the world’s most exclusive private island [in the Caribbean], where Princess Margaret and Mick Jagger were regulars and scandals stayed hidden from the press.”

Mustique Island by Sarah McCoy: “A sun-splashed romp with a rich divorcée and her two wayward daughters in 1970s Mustique, the world’s most exclusive private island [in the Caribbean], where Princess Margaret and Mick Jagger were regulars and scandals stayed hidden from the press.”

Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy by Helen Fielding: I’d never read this second sequel from 2013, so we’re doing it for our August book club – after some darker reads, people requested something light! Bridget is now a single mother in her early 50s, but some things never change, like constant yo-yo dieting and obsessive chronicling of the stats of her life.

Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy by Helen Fielding: I’d never read this second sequel from 2013, so we’re doing it for our August book club – after some darker reads, people requested something light! Bridget is now a single mother in her early 50s, but some things never change, like constant yo-yo dieting and obsessive chronicling of the stats of her life. Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus: This year’s It book. I’m nearly halfway through and enjoying it, if not as rapturously as so many. Katherine Heiny meets John Irving is the vibe I’m getting. Elizabeth Zott is a scientist through and through, applying a chemist’s mindset to her every venture, including cooking, rowing and single motherhood in the 1950s.

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus: This year’s It book. I’m nearly halfway through and enjoying it, if not as rapturously as so many. Katherine Heiny meets John Irving is the vibe I’m getting. Elizabeth Zott is a scientist through and through, applying a chemist’s mindset to her every venture, including cooking, rowing and single motherhood in the 1950s.

This

This

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir