#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

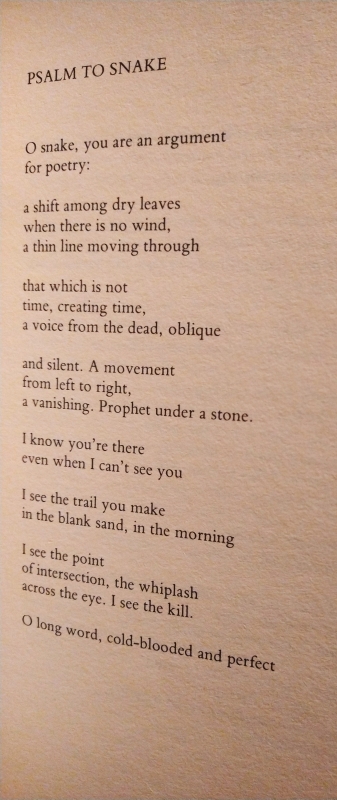

Interlunar (1984)

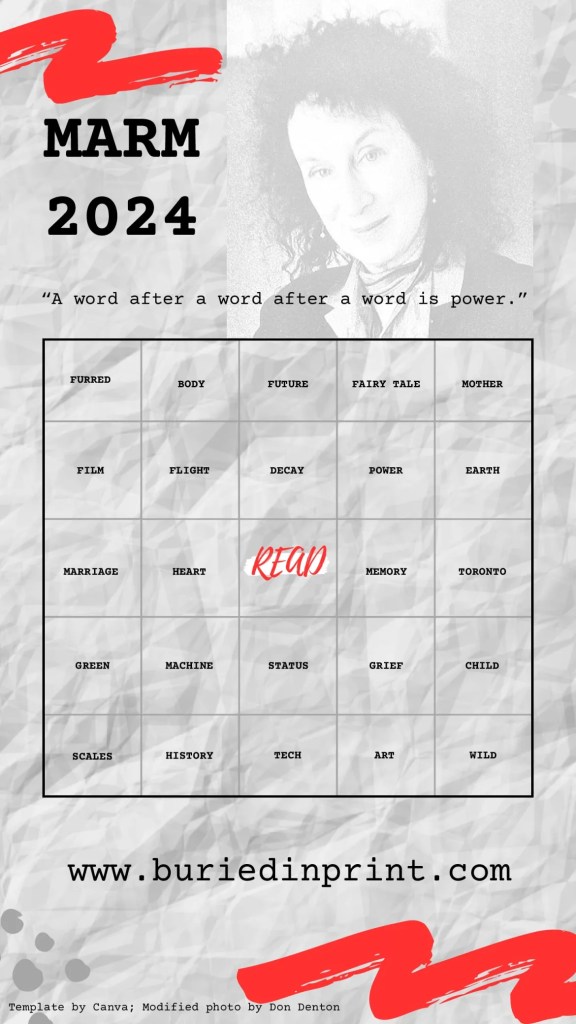

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

Eve Smith Event & Absurd Person Singular

Two literary events I attended recently…

On Friday afternoon I volunteered on stewarding and refreshments for an author chat held at my local public library. It was our first such event since before Covid! I’d not heard of Eve Smith, who is based outside Oxford and writes speculative – not exactly dystopian, despite the related display below – novels inspired by scientific and medical advancements encountered in the headlines. Genetics, in particular, has been a recurring topic in The Waiting Rooms (about antibiotic resistance), Off Target (gene editing of embryos), One (a one-child policy introduced in climate-ravaged future Britain) and The Cure (forthcoming in April 2025; transhumanism or extreme anti-ageing measures).

Smith used to work for an environmental organization and said that she likes to write about what scares her – which tends not to be outlandish horror but tweaked real-life situations. Margaret Atwood has been a big influence on her, and she often includes mother–daughter relationships. In the middle of the interview, she read from the opening of her latest novel, One. I reckon I’ll give her debut, The Waiting Rooms, a try. (I was interested to note that the library has classed it under Science Fiction but her other two novels with General Fiction.)

Then last night we went to see my husband’s oldest friend (since age four!) in his community theatre group’s production of Absurd Person Singular, a 1972 play by Alan Ayckbourn. I’ve seen and read The Norman Conquests trilogy plus another Ayckbourn play and was prepared for a suburban British farce, but perhaps not for how dated it would feel.

The small cast consists of three married couples. Ronald Brewster-Wright is a banker with an alcoholic wife, Marion. Sidney Hopcroft (wife: Jane) is a construction contractor and rising property tycoon and Geoffrey Jackson is a philandering architect with a mentally ill wife, Eva. Weaving all through is the prospect of a business connection between the three men: “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours,” as Sidney puts it to Ronald several times. After one of Geoffrey’s buildings suffers a disastrous collapse, he has to consider humbling himself enough to ask Sidney for work.

The small cast consists of three married couples. Ronald Brewster-Wright is a banker with an alcoholic wife, Marion. Sidney Hopcroft (wife: Jane) is a construction contractor and rising property tycoon and Geoffrey Jackson is a philandering architect with a mentally ill wife, Eva. Weaving all through is the prospect of a business connection between the three men: “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours,” as Sidney puts it to Ronald several times. After one of Geoffrey’s buildings suffers a disastrous collapse, he has to consider humbling himself enough to ask Sidney for work.

The three acts take place in each of their kitchens on subsequent Christmas Eves; the period kitchen fittings and festive decorations were a definite highlight. First, the Hopcrofts stress out over hosting the perfect cocktail party – which takes place off stage, with characters retreating in twos and threes to debrief in the kitchen. The next year, the jilted Eva makes multiple unsuccessful suicide attempts while her oblivious friends engage in cleaning and DIY. Finally, we’re at the Brewster-Wrights’ and the annoyingly cheerful Hopcrofts cajole the others, who aren’t in the Christmas spirit at all, into playing a silly musical chairs-like game.

With failure, adultery, alcoholism and suicidal ideation as strong themes, this was certainly a black comedy. Our friend Dave decided not to let his kids (10 and 7) come see it. He was brilliant as Sidney, not least because he genuinely is a DIY genius and has history of engaging people in dancing. But the mansplaining, criticism of his poor wife, and “Oh dear, oh dear” exclamations were pure Sidney. The other star of the show was Marion. Although the actress was probably several decades older than Ayckbourn’s intended thirtysomething characters, she brought Norma Desmond-style gravitas to the role. But it did mean that a pregnancy joke in relation to her and the reference to their young sons – the Brewster-Wrights are the only couple with children – felt off.

The director chose to give a mild content warning, printed in the program and spoken before the start: “Please be aware that this play was written in the 1970s and reflects the language and social attitudes of its time and includes themes of unsuccessful suicide attempts.” So the play was produced as is, complete with Marion’s quip about the cycles on Jane’s new washing machine: “Whites and Coloreds? It’s like apartheid!” The depiction of mental illness felt insensitive, although I like morbid comedy as much as the next person.

The director chose to give a mild content warning, printed in the program and spoken before the start: “Please be aware that this play was written in the 1970s and reflects the language and social attitudes of its time and includes themes of unsuccessful suicide attempts.” So the play was produced as is, complete with Marion’s quip about the cycles on Jane’s new washing machine: “Whites and Coloreds? It’s like apartheid!” The depiction of mental illness felt insensitive, although I like morbid comedy as much as the next person.

I can see why the small cast, silliness, and pre-Christmas domestic setting were tempting for amateur dramatics. There was good use of sound effects and the off-stage space, and a fun running gag about people getting soaked. I certainly grasped the message about not ignoring problems in hopes they’ll go away. But with so many plays out there, maybe this one could be retired?

The Bookshop Band in Abingdon & 20 Books of Summer, 6: Orphans of the Carnival by Carol Birch

The Bookshop Band have been among my favourite musical acts since I first saw play live at the Hungerford Literary Festival in 2014. Initially formed of three local musicians for hire, they got their start in 2010 as the house band at Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, England. For their first four years, they wrote a pair of original songs about a new book, often the very day of an author’s event in the shop, and performed them on guitar, cello, and ukulele as an interlude to the evening’s reading and discussion.

Notable songs from their first 13 albums are based on Glow by Ned Beauman (“We Are the Foxes”), Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller (“Bobo and the Cattle”), The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Rachel Joyce (“How Not to Woo a Woman”), and Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel (“You Make the Best Plans, Thomas”). They have also written responses to classic literature, with songs inspired by Alice in Wonderland, various Shakespeare plays, and a compilation of first lines called “Once Upon a Time.”

I got to see the band live five times pre-pandemic, even after husband-and-wife-duo Ben Please and Beth Porter moved nearly 400 miles away to Wigtown, the Book Town of Scotland. During the first six months of Covid-19 lockdown, the livestream concerts from their attic were weekly treats to look forward to. They also interviewed authors for a breakfast chat show as part of the Wigtown Book Festival, which went online that year.

In the years since, the band has kept busy with other projects (not to mention two children). Porter sings and performs on the two Spell Songs albums based on Robert Macfarlane’s The Lost Words and its sequel. Together they composed the soundtrack to Aardman Animations’ short film, Robin Robin (2021) – winning Best Music at the British Animation Awards, and wrote an album of songs based on Scottish children’s literature. And they have continued writing one-off book songs, such as for the launch of Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton. (I’m disappointed their songs about All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and The Spinning Heart by Donal Ryan still haven’t made it onto record.)

I’ve been enthusing about them for nearly a decade, but they’ve remained mostly under the radar in that time. Not so any longer; their recent album Emerge, Return was produced by Pete Townshend of The Who; the production value has notably advanced while retaining their indie spirit. Foreword Reviews kindly agreed to pay me to fangirl – er, write a blog – about Emerge, Return and the tour supporting it, so I’ll leave it there for the music criticism (their complete discography is now available on Bandcamp and Spotify). I’ll just add that a number of these ‘new’ songs have been kicking around for six to ten years but went unrecorded until now. For that reason, I worried that it might feel like a collection of cast-offs, but in fact they’ve managed to produce something sonically and thematically cohesive. It’s darker than some of their previous work, with moody minor chords and slightly sinister subjects.

I’ve been enthusing about them for nearly a decade, but they’ve remained mostly under the radar in that time. Not so any longer; their recent album Emerge, Return was produced by Pete Townshend of The Who; the production value has notably advanced while retaining their indie spirit. Foreword Reviews kindly agreed to pay me to fangirl – er, write a blog – about Emerge, Return and the tour supporting it, so I’ll leave it there for the music criticism (their complete discography is now available on Bandcamp and Spotify). I’ll just add that a number of these ‘new’ songs have been kicking around for six to ten years but went unrecorded until now. For that reason, I worried that it might feel like a collection of cast-offs, but in fact they’ve managed to produce something sonically and thematically cohesive. It’s darker than some of their previous work, with moody minor chords and slightly sinister subjects.

I’ve often found that the band will zero in on a detail, scene, or idea that never would have stood out to me while reading a book but, in retrospect, evokes the whole with great success. I decided to test this out by reading Carol Birch’s Orphans of the Carnival in the weeks leading up to seeing them on their months-long UK summer/autumn tour. It’s a historical novel about real-life 1850s Mexican circus “freak” Julia Pastrana, who had congenital conditions that caused her face and body to be covered in thick hair and her jaw and lips to protrude. Cruel contemporaries called her the world’s ugliest woman and warned that pregnant women should not be allowed to see her on tour lest the shock cause them to miscarry. Medical doctors posited, in all seriousness, that she was a link between humans and orangutans.

My copy of Birch’s novel was a remainder, and it is certainly a minor work compared to the Booker Prize-shortlisted Jamrach’s Menagerie. Facts about Julia’s travel itinerary and fellow oddballs quickly grow tedious, and while one of course sympathizes when children throw rocks at her, she never becomes a fully realized character rather than a curiosity.

There is also a bizarre secondary storyline set in 1983, in which Rose fills her London apartment with hoarded objects, including a doll she rescues from a skip and names Tattoo. She becomes obsessed with the idea of visiting a doll museum in Mexico. I thought that Tattoo would turn out to be Julia’s childhood doll Yatzi (similar to in A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power, where dolls have sentimental and magical power across the centuries), but the connection, though literal, was not as I expected. It’s more grotesque than that. And stranger than fiction, frankly.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

Birch sticks to the known details of Julia’s life. She had various agents, the final one being Theo Lent, who married her. (In the novel, he can’t bring himself to kiss her, but he can, you know, impregnate her.) She died of a fever soon after childbirth. Her son, Theo Junior, who inherited her hypertrichosis, also died within days. Both bodies were embalmed, sold, and exhibited. Theo then married another hairy woman, Marie Bartel of Germany, who took the name “Zenora” and posed as Julia’s sister. Theo died, syphilitic (or so Birch implies) and insane, in a Russian asylum. Julia and Theo Junior’s remains were displayed and mislaid at various points over the years, with Julia’s finally repatriated to Mexico for a proper burial in 2013. In the novel, Tattoo is, in fact, Theo Junior’s mummy.

Birch sticks to the known details of Julia’s life. She had various agents, the final one being Theo Lent, who married her. (In the novel, he can’t bring himself to kiss her, but he can, you know, impregnate her.) She died of a fever soon after childbirth. Her son, Theo Junior, who inherited her hypertrichosis, also died within days. Both bodies were embalmed, sold, and exhibited. Theo then married another hairy woman, Marie Bartel of Germany, who took the name “Zenora” and posed as Julia’s sister. Theo died, syphilitic (or so Birch implies) and insane, in a Russian asylum. Julia and Theo Junior’s remains were displayed and mislaid at various points over the years, with Julia’s finally repatriated to Mexico for a proper burial in 2013. In the novel, Tattoo is, in fact, Theo Junior’s mummy.

Two Bookshop Band songs from the new album are about the novel: “Doll” and “Waggons and Wheels.” “Doll” is one of the few more lighthearted numbers on the album. It ended up being a surprise favourite track for me (along with the creepy “Eve in Your Garden,” about Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments, and “Room for Three,” a sombre yet resolute epic written for the launch of Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage) because of its jaunty music-hall tempo; the pattern of repeating most nouns three times; and the hand claps, “deedily” vocal fills, unhinged recorder playing, and springy sound effects. The lyrics are almost a riddle: “When’s a doll (doll doll) not a doll (doll doll)?” They somehow avoid all spoilers while conveying something of the mental instability of a couple of characters.

The gorgeous “Waggons and Wheels” picks up on the melancholy tone and parental worries of earlier tracks from the album. The chorus has a wistful air as Julia ponders the passage of time and her constant isolation: “old friends, new deals / Winter or spring, I am hiding … Winter or spring, I’ll be travelling.” Porter’s mellow soprano tempers Julia’s outrage at mistreatment: “who are you to shout / Indecency and shame? / Shocking, I shock, so lock me out / I’m locked into this face.” She fears, too, what will happen to her child, “a beast or a boy, a monster or joy”. Listening to the song, I feel that the band saw past the specifics to plumb the universal feelings that get readers empathizing with Julia as a protagonist. They’ve gotten to the essence of the story in a way that Birch perhaps never did. Mediocre book; lovely songs. (New (bargain) purchase – Dollar Tree, Bowie, Maryland) ![]()

I caught the Emerge, Return tour at St Nicolas’ Church in Abingdon (an event hosted by Mostly Books) last night. It was my sixth time seeing the Bookshop Band in concert – see also my write-ups of two 2016 events plus one in 2018 and another in 2019 – but the first time in person since the pandemic. I got to show off my limited-edition T-shirt. How nice it was to meet up again with blogger friend Annabel, too! Fun fact for you: Ben was born in Abingdon but hadn’t been back since he was two. Beth’s cousin turned up to the show as well. Although they have their daughters, 2 and 7, on the tour with them, they were being looked after elsewhere for the evening so the parents could relax a bit. Across the two sets, they played seven tracks from the new album, six old favourites, and two curios: one Spell Song, and an untitled song they wrote for the audiobook of Jackie Morris’s The Unwinding. It was a brilliant evening!

Some 2023 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Shortest book read this year: Pitch Black by Youme Landowne and Anthony Horton (40 pages)

Authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood, Deborah Levy and Brian Turner (3 books each); Amy Bloom, Simone de Beauvoir, Tove Jansson, John Lewis-Stempel, W. Somerset Maugham, L.M. Montgomery and Maggie O’Farrell (2 books each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Setting aside the ubiquitous Penguin and its many imprints) Carcanet (11 books) and Picador/Pan Macmillan (also 11), followed by Canongate (7).

My top author discoveries of the year: Michelle Huneven and Julie Marie Wade

My proudest bookish accomplishment: Helping to launch the Little Free Library in my neighbourhood in May, and curating it through the rest of the year (nearly daily tidying; occasional culling; requesting book donations)

Most pinching-myself bookish moments: Attending the Booker Prize ceremony; interviewing Lydia Davis and Anne Enright over e-mail; singing carols after-hours at Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Books that made me laugh: Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson, The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt, two by Katherine Heiny, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Books that made me cry: A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney, Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout, Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Best book club selections: By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah and The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

Shortest book title encountered: Lo (the poetry collection by Melissa Crowe), followed by Bear, Dirt, Milk and They

Best 2023 book titles: These Envoys of Beauty and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore (shame the contents didn’t live up to it!)

Biggest disappointment: Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

A 2023 book that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

The worst books I read this year: Monica by Daniel Clowes, They by Kay Dick, Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy and Self-Portrait in Green by Marie Ndiaye (1-star ratings are extremely rare for me; these were this year’s four)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age. In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment.

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment.

Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.

Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.