Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

Nonfiction November: Two Memoirs of Biblical Living by Evans and Jacobs

I love a good year-challenge narrative and couldn’t resist considering these together because of the shared theme. Sure, there’s something gimmicky about a rigorously documented attempt to obey the Bible’s literal commandments as closely as possible in the modern day. But these memoirs arise from sincere motives, take cultural and theological matters seriously, and are a lot of fun to read.

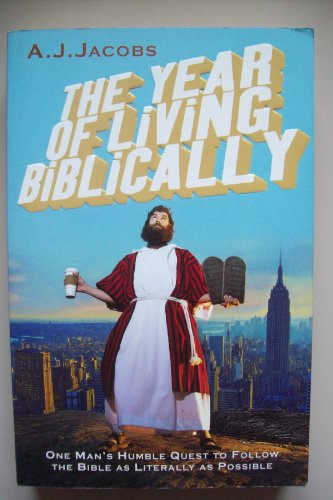

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs (2007)

Jacobs came up with the idea, so I’ll start with him. His first book, The Know-It-All, was about absorbing as much knowledge as possible by reading the encyclopaedia. This starts in similarly intellectual fashion with a giant stack of Bible translations and commentaries. From one September to the next, Jacobs vows, he’ll do his best to understand and implement commandments from both the Old and New Testaments. It’s not a completely random choice of project in that he’s a secular Jew (“I’m Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”). Firstly, and most obviously, he stops shaving and getting haircuts. “As I write this, I have a beard that makes me resemble Moses. Or Abe Lincoln. Or [Unabomber] Ted Kaczynski. I’ve been called all three.” When he also takes to wearing all white, he really stands out on the New York subway system. Loving one’s neighbour isn’t easy in such an antisocial city, but he decides to try his best.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

The book is a near-daily journal, with a new rule or three grappled with each day. There are hundreds of strange and culturally specific guidelines, but the heart issues – covetousness, lust – pose more of a challenge. Alongside his work as a journalist for Esquire and this project, Jacobs has family stuff going on: IVF results in his wife’s pregnancy with twin boys. Before they become a family of five, he manages to meet some Amish people, visit the Creation Museum, take a trip to the Holy Land to see a long-lost uncle, and engage in conversation with Evangelicals across the political spectrum, from Jerry Falwell’s megachurch to Tony Campolo (who died just last week). Jacobs ends up a “reverent agnostic.” We needn’t go to such extremes to develop the gratitude he feels by the end, but it sure is a hoot to watch him. This has just the sort of amusing, breezy yet substantial writing that should engage readers of Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Jon Ronson. (Free mall bookshop) ![]()

A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master” by Rachel Held Evans (2012)

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

It’s a sweet, self-deprecating book. You can definitely tell that she was only 29 at the time she started her project. It’s okay with me that Evans turned all her literal intentions into more metaphorical applications by the end of the year. She concludes that the Church has misused Proverbs 31: “We abandoned the meaning of the poem by focusing on the specifics, and it became just another impossible standard by which to measure our failures. We turned an anthem into an assignment, a poem into a job description.” Her determination is not to obsess over rules but to continue with the habits that benefited her spiritual life, and to champion women whenever she can. I suspect this is a lesser entry from Evans’s oeuvre. She died too soon – suddenly in 2019, of brain swelling after a severe allergic reaction to an antibiotic – but remains a valued voice, and I’ll catch up on the rest of her books. Searching for Sunday, for instance, was great, and I’m keen to read Evolving in Monkey Town (about living in Dayton, Tennessee, where the famous Scopes Monkey Trial took place). (Birthday gift from my wish list, 2023) ![]()

My Year in Novellas (#NovNov24)

Here at the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about the novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a special shelf of short books that I add to throughout the year. When at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, a Little Free Library, or the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about my piles for November. But I do read novellas at other times of year, too. Forty-four of them between December 2023 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year it was 46, so it seems like that’s par for the course). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My favourites of the ones I’ve already covered on the blog would probably be (nonfiction) Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti and (fiction) Aimez-vous Brahms by Françoise Sagan. My proudest achievements are: reading the short graphic novel Broderies by Marjane Satrapi in the original French at our Parisian Airbnb in December; and managing two rereads: Heartburn by Nora Ephron and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Of the short books I haven’t already reviewed here, I’ve chosen two gems, one fiction and one nonfiction, to spotlight in this post:

Fiction

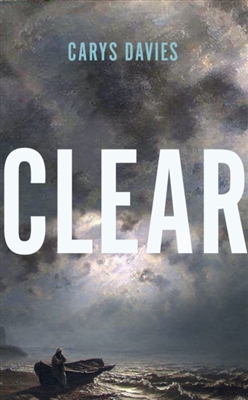

Clear by Carys Davies

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

In my book club, opinions differed slightly as to the central relationship and the conclusion, but we agreed that it was beautifully done, with so much conveyed in the concise length. This received our highest rating ever, in fact. I’d read Davies’ West and not appreciated it as much, although looking back I can see that it was very similar: one or a few character(s) embarked on unusual and intense journey(s); a plucky female character; a heavy sense of threat; and an improbably happy ending. It was the ending that seemed to come out of nowhere and wasn’t in keeping with the tone of the rest of the novella that made me mark West down. Here I found the writing cinematic and particularly enjoyed Mary as a strong character who escaped spinsterhood but even in marriage blazes her own trail and is clever and creative enough to imagine a new living situation. And although the ending is sudden and surprising, it nevertheless seems to arise naturally from what we know of the characters’ emotional development – but also sent me scurrying back to check whether there had been hints. One of my books of the year for sure. ![]()

Nonfiction

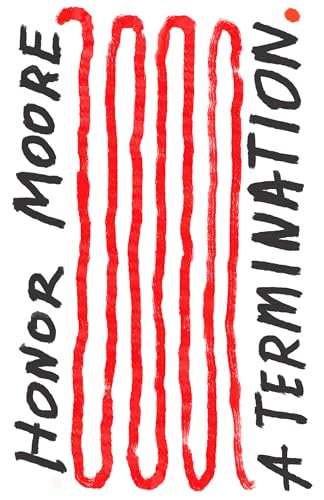

A Termination by Honor Moore

Poet and memoirist Honor Moore’s A Termination is a fascinatingly discursive memoir that circles her 1969 abortion and contrasts societal mores across her lifetime.

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

Family and social factors put Moore’s experiences into perspective. The first doctor she saw refused Moore’s contraception request because she was unmarried. Her mother, however, bore nine children and declined to abort a pregnancy when advised to do so for medical reasons. Moore observes that she made her own decision almost 10 years before “the word choice replaced pro abortion.”

This concise work is composed of crystalline fragments. The stream of consciousness moves back and forth in time, incorporating occasional second- and third-person narration as well as highbrow art and literature references. Moore writes one scene as if it’s in a play and imagines alternative scenarios in which she has a son; though she is curious, she is not remorseful. The granular attention to women’s lives recalls Annie Ernaux, while the kaleidoscopic yet fluid approach is reminiscent of Sigrid Nunez’s work. It’s a stunning rendering of steps on her childfree path. ![]()

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I currently have four novellas underway and plan to start some more this weekend. I have plenty to choose from!

Everyone’s getting in on the act: there’s an article on ‘short and sweet books’ in the November/December issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I’m an associate editor; Goodreads sent around their usual e-mail linking to a list of 100 books under 250 or 200 pages to help readers meet their 2024 goal. Or maybe you’d like to join in with Wafer Thin Books’ November buddy read, the Ugandan novella Waiting by Goretti Kyomuhendo (2007).

Why not share some recent favourite novellas with us in a post of your own?

A Review for PKD Awareness Day: The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall

Today is PKD Awareness Day. Because the author and I both have polycystic kidney disease, I’m doing something I rarely do and reprinting an early review of mine that has already appeared on Shelf Awareness. I could hardly believe it when I was trawling through the list of review book offers and saw that Eiren Caffall also has PKD, then even more astonished to learn that it is a major theme in her memoir, which also weaves in marine biology and environmental concerns. An altogether intriguing book that, of course, held personal interest for me.

The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall

Eiren Caffall’s debut is an ardent elegy for her illness-haunted family and for the ailing marine environments that inspire her.

For centuries, the author’s family has been subject to “the Caffall Curse.” Polycystic kidney disease, a degenerative genetic condition, causes fluid-filled cysts to proliferate in a person’s enlarged kidneys. PKD can involve pain, fatigue, high blood pressure, kidney failure, and a heightened risk of brain aneurysm. Given Caffall’s paternal family history, she expected to die before age 50.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

In 2014, Caffall, then a single mother, took her nine-year-old son, Dex, on vacation to the Gulf of Maine. During the trip, she had a fall that prompted a seizure, and she and Dex were evacuated from Monhegan Island by Coast Guard ship. Although no further seizures ensued and no clear cause emerged, the crisis served as a wake-up call, reminding her of how serious PKD is and that it might afflict her son as well.

The book draws fascinating connections between personal experiences and ecological threats. Caffall structures her story as a gallery of endangered marine animals such as the Longfin Inshore Squid and Humpback Whale, tracing their history and exposing the dangers they face in degraded environments. Red tides (massive algal blooms) and floods are apt metaphors for physical trials: “the Sound was dying, hypoxic … from an overwhelm of nutrients flooding an ecosystem—nitrogen, phosphorus, imbalanced saline—the same things that overwhelm a body when kidneys can no longer filter blood properly.”

Re-created scenes enliven accounts of family illness and therapeutic developments. The lyrical hybrid narrative, informed by scientific journals and government publications, is as impassioned about restoring the environment as it is about ensuring equality of access to health care. Personal and species extinction are just cause for “permanent mourning,” Caffall writes, but adapting to change keeps hope alive.

(Coming out in the USA from Row House Publishing on October 15th)

Posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

[I couldn’t help but compare family members’ trajectories. Like her father, my mother was on dialysis for a time before getting a transplant, from her cousin. Like her aunt, my uncle died of a brain aneurysm, which is an associated risk. It sounds like Caffall has been much more severely affected than I have thus far. She is 53 and on Tolvaptan, a cutting-edge drug that slows the growth of cysts and thus the decline in kidney function. But even within families, the disease course is so varied. A cousin of mine was in her thirties when she had a transplant, whereas I am still very much in the early stages.]

A shout-out to the PKD Foundation in the States and the PKD Charity here in the UK.

A related post: In 2017 I reviewed four books for World Kidney Day.

From the supermarket last week: a plum that wanted to be a kidney.

August Releases: Sarah Manguso (Fiction), Sarah Moss (Memoir), and Carl Phillips (Poetry)

Today I feature a new-to-me poet and two women writers whose careers I’ve followed devotedly but whose latest books – forthright yet slippery; their genre categories could easily be reversed – I found very emotionally difficult to read. Gruelling, almost, but admirable. Many rambling thoughts ensue. Then enjoy a nice poem.

Liars by Sarah Manguso

As part of a profile of Manguso and her oeuvre for Bookmarks magazine, I wrote a synopsis and surveyed critical opinion; what follow are additional subjective musings. I’ve read six of her nine books (all but the poetry and an obscure flash fiction collection) and I esteem her fragmentary, aphoristic prose, but on balance I’m fonder of her nonfiction. Had Liars been marketed as a diary of her marriage and divorce, Manguso might have been eviscerated for the indulgence and one-sided presentation. With the thinnest of autofiction layers, is it art?

Jane recounts her doomed marriage, from the early days of her relationship with John Bridges to the aftermath of his affair and their split. She is a writer and academic who sacrifices her career for his financially risky artistic pursuits. Especially once she has a baby, every domestic duty falls to her, while he keeps living like a selfish stag and gaslights her if she tries to complain, bringing up her history of mental illness. The concise vignettes condense 14+ years into 250 pages, which is a relief because beneath the sluggish progression is such repetition of type of experiences that it could feel endless. John’s last name might as well be Doe: The novel presents him – and thus all men – as despicable and useless, while women are effortlessly capable and, by exhausting themselves, achieve superhuman feats. This is what heterosexual marriage does to anyone, Manguso is arguing. Indeed, in a Guardian interview she characterized this as a “domestic abuse novel,” and elsewhere she has said that motherhood can be unlinked from patriarchy, but not marriage.

Let’s say I were to list my every grievance against my husband from the last 17+ years: every time he left dirty clothes on the bedroom floor (which is every day); every time he loaded the dishwasher inefficiently (which is every time, so he leaves it to me); every time he failed to seal a packet or jar or Tupperware properly (which – yeah, you get the picture) – and he’s one of the good guys, bumbling rather than egotistical! And he’d have his own list for me, too. This is just what we put up with to live with other people, right? John is definitely worse (“The difference between John and a fascist despot is one of degree, not type”). But it’s not edifying, for author or reader. There may be catharsis to airing every single complaint, but how does it help to stew in bitterness? Look at everything I went through and validate my anger.

There are bright spots: Jane’s unexpected transformation into a doting mother (but why must their son only ever be called “the child”?), her dedication to her cat, and the occasional dark humour:

So at his worst, my husband was an arrogant, insecure, workaholic, narcissistic bully with middlebrow taste, who maintained power over me by making major decisions without my input or consent. It could still be worse, I thought.

Manguso’s aphoristic style makes for many quotably mordant sentences. My feelings vacillated wildly, from repulsion to gung-ho support; my rating likewise swung between extremes and settled in the middle. I felt that, as a feminist, I should wholeheartedly support a project of exposing wrongs. It’s easy to understand how helplessness leads to rage, and how, considering sunk costs, a partner would irrationally hope for a situation to improve. So I wasn’t as frustrated with Jane as some readers have been. But I didn’t like the crass sexual language, and on the whole I agreed with Parul Sehgal’s brilliant New Yorker review that the novel is so partial and the tone so astringent that it is impossible to love. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

And a quote from the Moss memoir (below) to link the two books: “Homes are places where vulnerable people are subject to bullying, violence and humiliation behind closed doors. Homes are places where a woman’s work is never done and she is always guilty.”

20 Books of Summer, #19:

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I’ve reviewed this memoir for Shelf Awareness (it’s coming out in the USA from Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 22nd) so will only give impressions, in rough chronological order:

Sarah Moss returns to nonfiction – YES!!!

Oh no, it’s in the second person. I’ve read too much of that recently. Fine for one story in a collection. A whole book? Not so sure. (Kirsty Logan got away with it, but only because The Unfamiliar is so short and meant to emphasize how matrescence makes you other.)

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

Once she starts discussing her childhood reading – what it did for her then and how she views it now – the book really came to life for me. And she very effectively contrasts the would-be happily ever after of generally getting better after eight years of disordered eating with her anorexia returning with a vengeance at age 46 – landing her in A&E in Dublin. (Oh! when she reads War and Peace over and over on a hospital bed and defiantly uses the clean toilets on another floor.) This crisis is narrated in the third person before a return to second person.

The tone shifts throughout the book, so that what threatens to be slightly cloying in the childhood section turns academically curious and then, somehow, despite the distancing pronouns, intimate. So much so that I found myself weeping through the last chapters over this lovely, intelligent woman’s ongoing struggles. As an overly cerebral person who often thinks it’s pesky to have to live in a body, I appreciated her probing of the body/mind divide; and as she tracks where her food issues came from, I couldn’t help but think about my sister’s years of eating disorders and my mother’s fear that it was all her fault.

Beyond Moss’s usual readers, I’d also recommend this to fans of Laura Freeman’s The Reading Cure and Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place.

Overall: shape-shifting, devastating, staunchly pragmatic. I’m not convinced it all hangs together (and I probably would have ended it at p. 255), but it’s still a unique model for transmuting life into art. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Will I remember individual poems? Unlikely. But the sense of chilly, clear-eyed reflection, yes. (Sample poem below) ![]()

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

Record of Where a Wind Was

Wave-side, snow-side,

little stutter-skein of plovers

lifting, like a mind

of winter—

We’d been walking

the beach, its unevenness

made our bodies touch,

now and then, at

the shoulders mostly,

with that familiarity

that, because it sometimes

includes love, can

become confused with it,

though they remain

different animals. In my

head I played a game with

the waves called Weapon

of Choice, they kept choosing

forgiveness, like the only

answer, as to them

it was, maybe. It’s a violent

world. These, I said, I choose

these, putting my bare hands

through the air in front of me.

Any other August releases you’d recommend?

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

20 Books of Summer, 11–13: Campbell, Julavits, Lu

Two solid servings of women’s life writing plus a novel about a Chinese woman stuck in roles she’s not sure she wants anymore.

Thunderstone: A true story of losing one home and discovering another by Nancy Campbell (2022)

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

The title refers to a fossil that has been considered a talisman in various cultures, and she needed the good luck during a period that involved accidental carbon monoxide poisoning and surgery for an ovarian abnormality (but it didn’t protect her books, which were all destroyed in a leaking shipping container – the horror!). I most enjoyed the longer entries where she muses on “All the potential lives I moved on from” during 20 years in Oxford and elsewhere, which makes me think that I would have preferred a more traditional memoir by her. Covid narratives feel really dated now, unfortunately. (New (bargain) purchase from Hungerford Bookshop with birthday voucher)

Directions to Myself: A Memoir by Heidi Julavits (2023)

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Mostly the memoir takes readers through everyday conversations the author has with friends and family about situations of inequality or harassment. Through her words she tries to gently steer her son towards more open-minded ideas about gender roles. She also entrances him and his sleepover friends with a real-life horror story about being chased through the French countryside by a man in a car. The tenor of her musings appealed to me, but already the details are fading. I suspect this will mean much more to a parent.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu (2023)

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy.

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy  Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages] After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]