My Most Anticipated Releases of the Second Half of 2019

Although over 90 books from the second half of the year are already on my radar, I’ve managed to narrow it down to the 15 July to November releases that I’m most excited about. I have access to a few of these already, and most of the rest I will try requesting as soon as I’m back from Milan. (These are given in release date order within thematic sections; the quoted descriptions are from the publisher blurbs on Goodreads.)

[By the way, here’s how I did with my most anticipated releases of the first half of the year:

- 16 out of 30 read; of those 9 were somewhat disappointing (i.e., 3 stars or below) – This is such a poor showing! Is it a matter of my expectations being too high?

- 10 I still haven’t managed to find

- 1 print review copy arrived recently

- 1 I have on my Kindle to read

- 1 I skimmed

- 1 I lost interest in]

Fiction

The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal [July 23, Pamela Dorman Books] Stradal’s Kitchens of the Great Midwest (2015) is one of my recent favorites. This one has a foodie theme again, and sounds a lot like Louise Miller’s latest – two sisters: a baker of pies and a founder of a small brewery. “Here we meet a cast of lovable, funny, quintessentially American characters eager to make their mark in a world that’s often stacked against them.”

The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal [July 23, Pamela Dorman Books] Stradal’s Kitchens of the Great Midwest (2015) is one of my recent favorites. This one has a foodie theme again, and sounds a lot like Louise Miller’s latest – two sisters: a baker of pies and a founder of a small brewery. “Here we meet a cast of lovable, funny, quintessentially American characters eager to make their mark in a world that’s often stacked against them.”

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton [August 6, Grand Central Publishing / Headline Review] As soon as I heard that this was narrated by a crow, I knew I was going to have to read it. (And the Seattle setting also ties in with Lyanda Lynn Haupt’s book.) “Humanity’s extinction has seemingly arrived, and the only one determined to save it is a foul-mouthed crow whose knowledge of the world around him comes from his TV-watching education.”

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton [August 6, Grand Central Publishing / Headline Review] As soon as I heard that this was narrated by a crow, I knew I was going to have to read it. (And the Seattle setting also ties in with Lyanda Lynn Haupt’s book.) “Humanity’s extinction has seemingly arrived, and the only one determined to save it is a foul-mouthed crow whose knowledge of the world around him comes from his TV-watching education.”

Inland by Téa Obreht [August 13, Random House / Weidenfeld & Nicolson] However has it been eight years since her terrific debut novel?! “In the lawless, drought-ridden lands of the Arizona Territory in 1893, two extraordinary lives collide. … [L]yrical, and sweeping in scope, Inland subverts and reimagines the myths of the American West.” The synopsis reminds me of Eowyn Ivey’s latest.

Inland by Téa Obreht [August 13, Random House / Weidenfeld & Nicolson] However has it been eight years since her terrific debut novel?! “In the lawless, drought-ridden lands of the Arizona Territory in 1893, two extraordinary lives collide. … [L]yrical, and sweeping in scope, Inland subverts and reimagines the myths of the American West.” The synopsis reminds me of Eowyn Ivey’s latest.

A Door in the Earth by Amy Waldman [August 27, Little, Brown and Company] I loved The Submission, Waldman’s 2011 novel about a controversial (imagined) 9/11 memorial. “Parveen Shamsa, a college senior in search of a calling, feels pulled between her charismatic and mercurial anthropology professor and the comfortable but predictable Afghan-American community in her Northern California hometown [and] travels to a remote village in the land of her birth to join the work of his charitable foundation.” (NetGalley download)

A Door in the Earth by Amy Waldman [August 27, Little, Brown and Company] I loved The Submission, Waldman’s 2011 novel about a controversial (imagined) 9/11 memorial. “Parveen Shamsa, a college senior in search of a calling, feels pulled between her charismatic and mercurial anthropology professor and the comfortable but predictable Afghan-American community in her Northern California hometown [and] travels to a remote village in the land of her birth to join the work of his charitable foundation.” (NetGalley download)

Bloomland by John Englehardt [September 10, Dzanc Books] “Bloomland opens during finals week at a fictional southern university, when a student walks into the library with his roommate’s semi-automatic rifle and opens fire. In this richly textured debut, Englehardt explores how the origin and aftermath of the shooting impacts the lives of three characters.” (print review copy from publisher)

Bloomland by John Englehardt [September 10, Dzanc Books] “Bloomland opens during finals week at a fictional southern university, when a student walks into the library with his roommate’s semi-automatic rifle and opens fire. In this richly textured debut, Englehardt explores how the origin and aftermath of the shooting impacts the lives of three characters.” (print review copy from publisher)

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett [September 25, Harper / Bloomsbury UK] I’m more a fan of Patchett’s nonfiction, but will keep reading her novels thanks to Commonwealth. “At the end of the Second World War, Cyril Conroy combines luck and a single canny investment to begin an enormous [Philadelphia] real estate empire … Set over … five decades, The Dutch House is a dark fairy tale about two smart people who cannot overcome their past.”

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett [September 25, Harper / Bloomsbury UK] I’m more a fan of Patchett’s nonfiction, but will keep reading her novels thanks to Commonwealth. “At the end of the Second World War, Cyril Conroy combines luck and a single canny investment to begin an enormous [Philadelphia] real estate empire … Set over … five decades, The Dutch House is a dark fairy tale about two smart people who cannot overcome their past.”

Medical themes

Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions from Tiny Mortals about Death by Caitlin Doughty [September 10, W.W. Norton / September 19, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] I’ve read Doughty’s previous books about our modern attitude towards mortality and death customs around the world. She’s wonderfully funny and iconoclastic. Plus, how can you resist this title?! Although it sounds like it’s geared towards children, I’ll still read the book. “Doughty blends her mortician’s knowledge of the body and the intriguing history behind common misconceptions … to offer factual, hilarious, and candid answers to thirty-five … questions.”

Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions from Tiny Mortals about Death by Caitlin Doughty [September 10, W.W. Norton / September 19, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] I’ve read Doughty’s previous books about our modern attitude towards mortality and death customs around the world. She’s wonderfully funny and iconoclastic. Plus, how can you resist this title?! Although it sounds like it’s geared towards children, I’ll still read the book. “Doughty blends her mortician’s knowledge of the body and the intriguing history behind common misconceptions … to offer factual, hilarious, and candid answers to thirty-five … questions.”

The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care by Anne Boyer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux] “A week after her forty-first birthday, the acclaimed poet Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. … A genre-bending memoir in the tradition of The Argonauts, The Undying will … show you contemporary America as a thing both desperately ill and occasionally, perversely glorious.” (print review copy from publisher)

The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care by Anne Boyer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux] “A week after her forty-first birthday, the acclaimed poet Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. … A genre-bending memoir in the tradition of The Argonauts, The Undying will … show you contemporary America as a thing both desperately ill and occasionally, perversely glorious.” (print review copy from publisher)

From the author’s Twitter page.

Breaking and Mending: A doctor’s story of burnout and recovery by Joanna Cannon [September 26, Wellcome Collection] I haven’t gotten on with Cannon’s fiction, but a memoir should hit the spot. “A frank account of mental health from both sides of the doctor-patient divide, from the bestselling author of The Trouble with Goats and Sheep and Three Things About Elsie, based on her own experience as a doctor working on a psychiatric ward.”

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson [October 3, Doubleday / Transworld] His last few books have been somewhat underwhelming, but I’d read Bryson on any topic. He’s earned a reputation for making history, science and medicine understandable to laymen. “Full of extraordinary facts and astonishing stories, The Body: A Guide for Occupants is a brilliant, often very funny attempt to understand the miracle of our physical and neurological makeup.”

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson [October 3, Doubleday / Transworld] His last few books have been somewhat underwhelming, but I’d read Bryson on any topic. He’s earned a reputation for making history, science and medicine understandable to laymen. “Full of extraordinary facts and astonishing stories, The Body: A Guide for Occupants is a brilliant, often very funny attempt to understand the miracle of our physical and neurological makeup.”

The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be by Thomas Lynch [November 26, W.W. Norton] Lynch is such an underrated writer. A Michigan undertaker, he crafts essays and short stories about small-town life, the Irish-American experience and working with the dead. I discovered him through Greenbelt Festival some years back and have read three of his books. Some of what I’ve already read will likely be repeated here, but will be worth a second look anyway.

The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be by Thomas Lynch [November 26, W.W. Norton] Lynch is such an underrated writer. A Michigan undertaker, he crafts essays and short stories about small-town life, the Irish-American experience and working with the dead. I discovered him through Greenbelt Festival some years back and have read three of his books. Some of what I’ve already read will likely be repeated here, but will be worth a second look anyway.

Other Nonfiction

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [August 29, Profile Books] The Diary of a Bookseller was a treat in 2017. I’ve read the first two-thirds of this already while in Milan, and I wish I was in Wigtown instead! This sequel picks up in 2015 and is very much more of the same – the daily routines of buying and selling books and being out and about in a small town – so it’s up to you whether that sounds boring or comforting. I’m finding it strangely addictive. (NetGalley download)

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [August 29, Profile Books] The Diary of a Bookseller was a treat in 2017. I’ve read the first two-thirds of this already while in Milan, and I wish I was in Wigtown instead! This sequel picks up in 2015 and is very much more of the same – the daily routines of buying and selling books and being out and about in a small town – so it’s up to you whether that sounds boring or comforting. I’m finding it strangely addictive. (NetGalley download)

We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / October 10, Hamish Hamilton] Foer’s Eating Animals (2009) was a hard-hitting argument against eating meat. In this follow-up he posits that meat-eating is the single greatest contributor to climate change. “With his distinctive wit, insight and humanity, Jonathan Safran Foer presents this essential debate as no one else could, bringing it to vivid and urgent life, and offering us all a much-needed way out.”

We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / October 10, Hamish Hamilton] Foer’s Eating Animals (2009) was a hard-hitting argument against eating meat. In this follow-up he posits that meat-eating is the single greatest contributor to climate change. “With his distinctive wit, insight and humanity, Jonathan Safran Foer presents this essential debate as no one else could, bringing it to vivid and urgent life, and offering us all a much-needed way out.”

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie [September 19, Sort of Books] Jamie is a Scottish poet who writes exquisite essays about the natural world. I’ve read her two previous essay collections, Findings and Sightlines, as well as a couple of volumes of her poetry. “From the thawing tundra linking a Yup’ik village in Alaska to its hunter-gatherer past to the shifting sand dunes revealing the impressively preserved homes of neolithic farmers in Scotland, Jamie explores how the changing natural world can alter our sense of time.”

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie [September 19, Sort of Books] Jamie is a Scottish poet who writes exquisite essays about the natural world. I’ve read her two previous essay collections, Findings and Sightlines, as well as a couple of volumes of her poetry. “From the thawing tundra linking a Yup’ik village in Alaska to its hunter-gatherer past to the shifting sand dunes revealing the impressively preserved homes of neolithic farmers in Scotland, Jamie explores how the changing natural world can alter our sense of time.”

Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper [October 8, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / riverrun] Ties in with my special interest in women’s religious memoirs. “In November 2012, at the age of twenty-six, [Phelps-Roper] left [Westboro Baptist Church], her family, and her life behind. Unfollow is a story about the rarest thing of all: a person changing their mind. It is a fascinating insight into a closed world of extreme belief, a biography of a complex family, and a hope-inspiring memoir of a young woman finding the courage to find compassion.”

Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper [October 8, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / riverrun] Ties in with my special interest in women’s religious memoirs. “In November 2012, at the age of twenty-six, [Phelps-Roper] left [Westboro Baptist Church], her family, and her life behind. Unfollow is a story about the rarest thing of all: a person changing their mind. It is a fascinating insight into a closed world of extreme belief, a biography of a complex family, and a hope-inspiring memoir of a young woman finding the courage to find compassion.”

Which of these do you want to read, too?

What other upcoming 2019 titles are you looking forward to?

Three Recommended July Releases: Starling Days, Hungry, Supper Club

While very different, these three books tie together nicely with their themes of the hunger for food, adventure and/or love.

Starling Days by Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

(Coming on July 11th from Sceptre [UK])

Buchanan’s second novel reprises many of the themes from her first, Harmless Like You, including art, mental illness, and having one’s loyalties split across countries and cultures. Oscar and Mina have been together for over a decade, but their marriage got off to a bad start six months ago: on their wedding night Mina took an overdose, and Oscar was lucky to find her in time. The novel begins and ends with her contemplating suicide again; in between, Oscar takes her from New York City to England, where he grew up, for a change of scenery and to work on getting his father’s London flats ready to sell. For Mina, an adjunct professor and Classics tutor, it will be labeled a period of research on her monograph about the rare women who survive in Greek and Roman myth. But when work for his father’s Japanese import company takes Oscar back to New York, Mina is free to pursue her fascination with Phoebe, the sister of Oscar’s childhood friend.

Buchanan’s second novel reprises many of the themes from her first, Harmless Like You, including art, mental illness, and having one’s loyalties split across countries and cultures. Oscar and Mina have been together for over a decade, but their marriage got off to a bad start six months ago: on their wedding night Mina took an overdose, and Oscar was lucky to find her in time. The novel begins and ends with her contemplating suicide again; in between, Oscar takes her from New York City to England, where he grew up, for a change of scenery and to work on getting his father’s London flats ready to sell. For Mina, an adjunct professor and Classics tutor, it will be labeled a period of research on her monograph about the rare women who survive in Greek and Roman myth. But when work for his father’s Japanese import company takes Oscar back to New York, Mina is free to pursue her fascination with Phoebe, the sister of Oscar’s childhood friend.

Both Oscar and Mina have Asian ancestry and complicated, dysfunctional family histories. For Oscar, his father’s health scare is a wake-up call, reminding him that everything he has taken for granted is fleeting, and Mina’s uncertain mental and reproductive health force him to face the fact that they might never have children. Although I found this less original and compelling than Buchanan’s debut, I felt true sympathy for the central couple. It’s a realistic picture of marriage: you have to keep readjusting your expectations for a relationship the longer you’re together, and your family situation is inevitably going to have an impact on how you envision your future. I also admired the metaphors and the use of color.

The title is, I think, meant to refer to a sort of time outside of time when wishes can come true; in Mina’s case that’s these few months in London. Bisexuality is something you don’t encounter too often in fiction, so I guess that’s reason enough for it to be included here as a part of Mina’s story, though I wouldn’t say it adds much to the narrative. If it had been up to me, instead of birds I would have picked up on the repeated peony images (Mina has them tattooed up her arms, for instance) for the title and cover.

Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World by Jeff Gordinier

(Coming on July 9th from Tim Duggan Books [USA] and on October 3rd from Icon Books [UK])

Noma, René Redzepi’s restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has widely been considered the best in the world. In 2013, though, it suffered a fall from grace when some bad mussels led to a norovirus outbreak that affected dozens of customers. Redzepi wanted to shake things up and rebuild Noma’s reputation for culinary innovation, so in the four years that followed he also opened pop-up restaurants in Tulum, Mexico and Sydney, Australia. Journalist Jeff Gordinier, food and drinks editor at Esquire magazine, went along for the ride and reports on the Noma team’s adventures, painting a portrait of a charismatic, driven chef. For foodies and newbies alike, it’s a brisk, delightful tour through world cuisine as well as a shrewd character study. (Full review coming soon to BookBrowse.)

Noma, René Redzepi’s restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has widely been considered the best in the world. In 2013, though, it suffered a fall from grace when some bad mussels led to a norovirus outbreak that affected dozens of customers. Redzepi wanted to shake things up and rebuild Noma’s reputation for culinary innovation, so in the four years that followed he also opened pop-up restaurants in Tulum, Mexico and Sydney, Australia. Journalist Jeff Gordinier, food and drinks editor at Esquire magazine, went along for the ride and reports on the Noma team’s adventures, painting a portrait of a charismatic, driven chef. For foodies and newbies alike, it’s a brisk, delightful tour through world cuisine as well as a shrewd character study. (Full review coming soon to BookBrowse.)

Supper Club by Lara Williams

(Coming on July 9th from G.P. Putnam’s Sons [USA] and July 4th from Hamish Hamilton [UK])

“What could violate social convention more than women coming together to indulge their hunger and take up space?” Roberta and Stevie become instant besties when Stevie is hired as an intern at the fashion website where Roberta has been a writer for four years. Stevie is a would-be artist and Roberta loves to cook; they decide to combine their talents and host Supper Clubs that allow emotionally damaged women to indulge their appetites. The pop-ups take place at down-at-heel or not-strictly-legal locations, the food is foraged from dumpsters, and there are sometimes elaborate themes and costumes. These bacchanalian events tend to devolve into drunkenness, drug-taking, partial nudity and food fights.

The central two-thirds of the book alternates chapters between the present day, when Roberta is 28–30, and her uni days. I don’t think it can be coincidental that Roberta and Stevie are both feminized male names; rather, we are meant to ask to what extent all the characters have defined themselves in terms of the men in their lives. For Roberta, this includes the father who left when she was seven and now thinks he can send her chatty e-mails whenever he wants; the fellow student who raped her at uni; and the philosophy professor she dated for ages even though he treated her like an inconvenient child. Supper Club is performance art, but it’s also about creating personal meaning when family and romance have failed you.

The central two-thirds of the book alternates chapters between the present day, when Roberta is 28–30, and her uni days. I don’t think it can be coincidental that Roberta and Stevie are both feminized male names; rather, we are meant to ask to what extent all the characters have defined themselves in terms of the men in their lives. For Roberta, this includes the father who left when she was seven and now thinks he can send her chatty e-mails whenever he wants; the fellow student who raped her at uni; and the philosophy professor she dated for ages even though he treated her like an inconvenient child. Supper Club is performance art, but it’s also about creating personal meaning when family and romance have failed you.

I was slightly disappointed that Supper Club itself becomes less important as time goes on, and that we never get closure about Roberta’s father. I also found it difficult to keep the secondary characters’ backstories straight. But overall this is a great debut novel with strong themes of female friendship and food. Roberta opens most chapters with cooking lore and tips, and there are some terrific scenes set in cafés. I suspect this will mean a lot to a lot of young women. Particularly if you’ve liked Sweetbitter (Stephanie Danler) and Friendship (Emily Gould), give it a taste.

With thanks to Sapphire Rees of Penguin for the proof copy for review.

Have you read any other July releases you would recommend?

Wellcome Book Prize Longlist: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning

“all these ideas are swirling around inside your head at once, hurling through your mind, it is on fire, so when you speak it all comes out muddled and confused and no one can understand you.”

Like the other Wellcome-longlisted title I’ve highlighted so far, Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi, Mind on Fire explores mental health. Its subtitle is “A Memoir of Madness and Recovery,” and Irish playwright Fanning focuses on the ten years or so in his twenties and thirties when he struggled to get on top of his bipolar disorder and was in and out of mental hospitals – and even homeless on the streets of London for a short time.

Fanning had suffered from periods of depression ever since his mother’s death from cancer when he was 20, but things got much worse when he was 28 and living in Dublin. It was the summer of 1997 and he’d quit a full-time job to write stories and film scripts. What with the wild swings in his moods and energy levels, though, he found it increasingly difficult to get along with his father, with whom he was living. He also got kicked out of an artists’ residency, and on the way home his car ran out of petrol – such that when he called the police for help, it was for a breakdown in more than one sense. This was the first time he was taken to a psychiatric unit, at the Tyrone and Fermanagh Hospital, where he stayed for 10 days.

Fanning had suffered from periods of depression ever since his mother’s death from cancer when he was 20, but things got much worse when he was 28 and living in Dublin. It was the summer of 1997 and he’d quit a full-time job to write stories and film scripts. What with the wild swings in his moods and energy levels, though, he found it increasingly difficult to get along with his father, with whom he was living. He also got kicked out of an artists’ residency, and on the way home his car ran out of petrol – such that when he called the police for help, it was for a breakdown in more than one sense. This was the first time he was taken to a psychiatric unit, at the Tyrone and Fermanagh Hospital, where he stayed for 10 days.

In the years to come there would be many more hospital stays, delusions, medication regimes and odd behavior. There would also be time spent in America – an artists’ residency in Virginia, where he met Jennifer, and a fairly long-term relationship with her in New York City – and ups and downs in his writing career. For instance, he remembers that after reading Ulysses he was so despairingly convinced that he would never be a “real writer” like James Joyce that he burned hundreds of pages of work-in-progress.

This was a very hard book for me to rate. The prologue is a brilliant 6.5-page run-on sentence in the second person and present tense (I’ve quoted a fragment above) that puts you right into the author’s experience. It is a superb piece of writing. But nothing that comes after (a more standard first-person narrative, though still in the present tense for most of it) is nearly as good. As I’ve found in some other mental health memoirs, the cycle of hospitalizations and medications gets repetitive. It’s a whole lot of telling: this happened, then that happened. That’s also true of the flashbacks to his childhood and university years.

Due to his unreliable memory of his years lost to bipolar, Fanning has had to recreate his experiences from medical records, interviews with people who knew him, and so on. This insistence on documentary realism distances the reader from what should be intimate, terrifying events. I almost wondered if this would have worked better as a novel, allowing the author to invent more and thus better capture what it actually felt like to flirt with madness. There’s no denying the extremity of this period of his life, but I found myself unable to fully engage with the retelling. (Also, this is doomed to be mistaken for the superior Brain on Fire.)

My rating:

A favorite passage:

St John of God’s carries associations for me. I attended primary school not far from here, and used to see denizens of the hospital on their day outings, conspicuous in the way they walked: hunched over, balled up, constricted, eyes down to the ground, visibly disturbed. We cruelly referred to these people as ‘mentallers’, though never to their faces or within earshot, as we were frightened of them.

Now I, too, am a mentaller.

My gut feeling: There are several stronger memoirs on the longlist, so I don’t see this one making it through.

Longlist strategy:

- I’m about halfway through both The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

- I finally got hold of a library copy of Murmur by Will Eaves.

- The only two books I haven’t read and don’t have access to are Astroturf and Polio. I’ll only read these if they are on the shortlist. (Fingers crossed Astroturf doesn’t make it: it sounds awful!)

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

The Three Best Books I’ve Read So Far This Year

I’m very stingy with my 5-star ratings, so when I give one out you can be assured that a book is truly special. These three are all backlist reads – look out for my Classic of the Month post next week for a fourth that merits 5 stars – that are well worth seeking out. Out of the 50 books I’ve read so far this year, these are far and away the best.

This Sunrise of Wonder: Letters for the Journey by Michael Mayne (1995)

The cover image is Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow (1956).

I plucked this Wigtown purchase at random from my shelves and it ended up being just what I needed to lift me out of January’s funk. Mayne’s thesis is that experiencing wonder, “rare, life-changing moments of seeing or hearing things with heightened perception,” is what makes us human. Call it an epiphany (as Joyce did), call it a moment of vision (as Woolf did), call it a feeling of communion with the universe; whatever you call it, you know what he is talking about. It’s that fleeting sense that you are right where you should be, that you have tapped into some universal secret of how to be in the world.

Mayne believes poets, musicians and painters, in particular, reawaken us to wonder by encouraging us to pay close attention. His frame of reference is wide, with lots of quotations and poetry extracts; he has a special love for Turner, Monet and Van Gogh and for Rilke, Blake and Hopkins. Mayne was an Anglican priest and Dean of Westminster, so he comes at things from a Christian perspective, but most of his advice is generically spiritual and not limited to a particular religion. There are about 50 pages towards the end that are specifically about Jesus; one could skip those if desired.

The book is a series of letters written to his grandchildren from a chalet in the Swiss Alps one May to June. Especially with the frequent quotations and epigraphs, the effect is of a rich compendium of wisdom from the ages. I don’t often feel awake to life’s wonder – I get lost in its tedium and unfairness instead – but this book gave me something to aspire to.

A few of the many wonderful quotes:

“The mystery is that the created world exists. It is: I am. The mystery is life itself, together with the fact that however much we seek to explore and to penetrate them, the impenetrable shadows remain.”

“Once wonder goes; once mystery is dismissed; once the holy and the numinous count for nothing; then human life becomes cheap and it is possible with a single bullet to shatter that most miraculous thing, a human skull, with scarcely a second thought. Wonder and compassion go hand-in-hand.”

“this recognition of my true worth is something entirely different from selfishness, that turned-in-upon-myselfness of the egocentric. … It is a kind of blasphemy to view ourselves with so little compassion when God views us with so much.”

Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab by Christine Montross (2007)

When she was training to become a doctor in Rhode Island, Montross and her anatomy lab classmates were assigned an older female cadaver they named Eve. Eve taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a published poet, as evident in her lyrical exploration of the attraction and strangeness of working with the remnants of someone who was once alive. She sees the contrasts, the danger, the theatre, the wonder of it all:

When she was training to become a doctor in Rhode Island, Montross and her anatomy lab classmates were assigned an older female cadaver they named Eve. Eve taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a published poet, as evident in her lyrical exploration of the attraction and strangeness of working with the remnants of someone who was once alive. She sees the contrasts, the danger, the theatre, the wonder of it all:

“Stacked beside me on my sage green couch: this spinal column that wraps into a coil without muscle to hold it upright, hands and feet tied together with floss, this skull hinged and empty. A man’s teeth.”

“When I look at the tissues and organs responsible for keeping me alive, I am not reassured. The wall of the atrium is the thickness of an old T-shirt, and yet a tear in it means instant death. The aorta is something I have never thought about before, but if mine were punctured, I would exsanguinate, a deceptively beautiful word”

All through her training, Montross has to remind herself to preserve her empathy despite a junior doctor’s fatigue and the brutality of the work (“The force necessary in the dissections feels barbarous”), especially as the personal intrudes on her career through her grandparents’ decline and her plans to start a family with her wife – which I gather is more of a theme in her next book, Falling into the Fire, about her work as a psychiatrist. I get through a whole lot of medical reads, as any of my regular readers will know, but this one is an absolute stand-out for its lyrical language, clarity of vision, honesty and compassion.

There There by Tommy Orange (2018)

Had I finished this late last year instead of in the second week of January, it would have been vying with Lauren Groff’s Florida for the #1 spot on my Best Fiction of 2018 list.

The title – presumably inspired by both Gertrude Stein’s remark about Oakland, California (“There is no there there”) and the Radiohead song – is no soft pat of reassurance. It’s falsely lulling; if anything, it’s a warning that there is no consolation to be found here. Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least, with alcoholism, teen pregnancy, and gang violence as recurring sources of trauma. They have ongoing struggles with grief, mental illness and the far-reaching effects of fetal alcohol syndrome.

The title – presumably inspired by both Gertrude Stein’s remark about Oakland, California (“There is no there there”) and the Radiohead song – is no soft pat of reassurance. It’s falsely lulling; if anything, it’s a warning that there is no consolation to be found here. Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least, with alcoholism, teen pregnancy, and gang violence as recurring sources of trauma. They have ongoing struggles with grief, mental illness and the far-reaching effects of fetal alcohol syndrome.

The novel cycles through most of the characters multiple times, alternating between the first and third person (plus one second person chapter). As we see them preparing for the powwow, whether to dance and drum, meet estranged relatives, or get up to no good, we start to work out the links between everyone. I especially liked how Orange unobtrusively weaves in examples of modern technology like 3D printing and drones.

The writing in the action sequences is noticeably weaker, and I wasn’t fully convinced by the sentimentality-within-tragedy of the ending, but I was awfully impressed with this novel overall. I’d recommend it to readers of David Chariandy’s Brother and especially Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist. It was my vote for the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize (for the best first book, of any genre, published in 2018), and I was pleased that it went on to win.

Wellcome Book Prize Longlist: Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

“This is all, ultimately, a litany of madness—the colors of it, the sounds it makes in heavy nights, the chirping of it across the shoulder of the morning.”

Magic realism and mental illness fuel a swirl of disorienting but lyrical prose in this debut novel by a Nigerian–Tamil writer. Much of the story is told by the ọgbanje (an Igbo term for evil spirits) inhabiting Ada’s head: initially we have the first person plural voice of “Smoke” and “Shadow,” who deem “the Ada” a daughter of the python goddess Ala and narrate her growing-up years in Nigeria; later we get a first-person account from Asụghara, who calls herself “a child of trauma” and leads Ada into promiscuity and drinking when she is attending college in Virginia.

Magic realism and mental illness fuel a swirl of disorienting but lyrical prose in this debut novel by a Nigerian–Tamil writer. Much of the story is told by the ọgbanje (an Igbo term for evil spirits) inhabiting Ada’s head: initially we have the first person plural voice of “Smoke” and “Shadow,” who deem “the Ada” a daughter of the python goddess Ala and narrate her growing-up years in Nigeria; later we get a first-person account from Asụghara, who calls herself “a child of trauma” and leads Ada into promiscuity and drinking when she is attending college in Virginia.

The unusual choice of narrators links Freshwater to other notable works of Nigerian literature: a spirit child relates Ben Okri’s Booker Prize-winning 1991 novel, The Famished Road, while Chigozie Obioma’s brand-new novel, An Orchestra of Minorities, is from the perspective of the main character’s chi, or life force. Emezi also contrasts indigenous belief with Christianity through Ada’s troubled relationship with “Yshwa” or “the christ.”

These spirits are parasitic and have their own agenda, yet express fondness for their hostess. “The Ada should have been nothing more than a pawn, a construct of bone and blood and muscle … But we had a loyalty to her, our little container.” So it’s with genuine pity that they document Ada’s many troubles, starting with her mother’s departure for a mental hospital and then for a job in Saudi Arabia, and continuing on through Ada’s cutting, anorexia and sexual abuse by a boyfriend. Late on in the book, Emezi also introduces gender dysphoria that causes Ada to get breast reduction surgery; to me, this felt like one complication too many.

The U.S. cover

From what I can glean from the Acknowledgments, it seems Ada’s life story might mirror Emezi’s own – at the very least, a feeling of being occupied by multiple personalities. It’s a striking book with vivid scenes and imagery, but I wanted more of Ada’s own voice, which only appears in a few brief sections totalling about six pages. The conflation of the abstract and the concrete didn’t quite work for me, and the whole is pretty melodramatic. Although I didn’t enjoy this as much as some other inside-madness tales I’ve read (such as Die, My Love and Everything Here Is Beautiful), I can admire the attempt to convey the reality of mental illness in a creative way.

My rating:

My gut feeling: I’ve only gotten to two of the five novels longlisted for the Prize, so it’s difficult to say what from the fiction is strong enough to make it through to the shortlist. Of the two, though, I think Sight would be more likely to advance than Freshwater.

Do you think this is a novel that you’d like to read?

Longlist strategy:

- I’m about one-fifth of the way through Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning, which I plan to review in early March.

- I’ve also been sent review copies of The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh and look forward to reading them, though I might not manage to before the shortlist announcement.

- I’ve placed a library hold on Murmur by Will Eaves; if it arrives in time, I’ll try to read it before the shortlist announcement, since it’s fairly short.

- Barring these, there are only two remaining books that I haven’t read and don’t have access to: Astroturf and Polio. I’ll only read these if they make the shortlist.

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

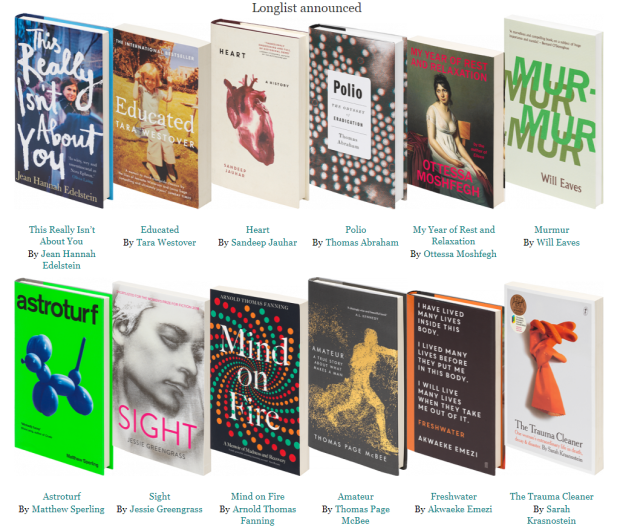

The Wellcome Book Prize 2019 Longlist: Reactions & Shadow Panel Reading Strategy

The 2019 Wellcome Book Prize longlist was announced on Tuesday. From the prize’s website, you can click on any of these 12 books’ covers, titles or authors to get more information about them.

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the prize. As always, it’s a strong and varied set of nominees, with an overall focus on gender and mental health. Here are some initial thoughts (see also Laura’s thorough rundown of the 12 nominees):

- I correctly predicted just two, Sight by Jessie Greengrass and Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar, but had read another three: This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein, Amateur by Thomas Page McBee, and Educated by Tara Westover (reviewed for BookBrowse).

- I’m particularly delighted to see Edelstein on the longlist as her book was one of my runners-up from last year and deserves more attention.

- I’m not personally a huge fan of the Greengrass or McBee books, but can certainly see why the judges thought them worthy of inclusion.

- Though it’s a brilliant memoir, I never would have thought to put Educated on my potential Wellcome list. However, the more I think about it, the more health elements it has: her father’s possible bipolar disorder, her brother’s brain damage, her survivalist family’s rejection of modern medicine, her mother’s career in midwifery and herbalism, and her own mental breakdown at Cambridge.

- Books I knew about and was keen to read but hadn’t thought of in conjunction with the prize: The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

- Novels I had heard of but wasn’t necessarily interested in beforehand: Murmur by Will Eaves and Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi. I went to get Freshwater from the library the afternoon of the longlist announcement and am now 60 pages in. I’d be tempted to call it this year’s Stay with Me except that the magic realist elements are much stronger here, reminding me of what I know about work by Chigozie Obioma and Ben Okri. The novel is narrated in the first person plural by a pair of (gods? demons? spirits?) inhabiting Ada’s head.

- And lastly, there are a few books I had never even heard of: Polio: The Odyssey of Eradication by Thomas Abraham, Mind on Fire: A Memoir of Madness and Recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning, and Astroturf by Matthew Sperling. I’m keen on the Fanning but not so much on the other two. Polio will likely make it to the shortlist as this year’s answer to The Vaccine Race; if it does, I’ll read it then.

Some statistics on this year’s longlist, courtesy of a press release sent by Midas PR:

- Five novels (two more than last year – I think we can see the influence of novelist Elif Shafak), five memoirs, one biography, and one further nonfiction title

- Six debut authors

- Six titles from independent publishers (Canongate, CB Editions, Faber & Faber, Oneworld, Hurst Publishers, and The Text Publishing Company)

- Most of the authors are British or American, while Fanning is Irish (Emezi is Nigerian-American, Jauhar is Indian-American, and Krasnostein is Australian-American).

Chair of judges Elif Shafak writes: “In a world that remains sadly divided into echo chambers and mental ghettoes, this prize is unique in its ability to connect various disciplines: medicine, health, literature, art and science. Reading and discussing at length all the books on our list has been fascinating from the very start. We now have a wonderful longlist, of which we are all very proud. Although it sure won’t be easy to choose the shortlist, and then, finally, the winner, I am thrilled about and truly grateful for this fascinating journey through stories, ideas, ground-breaking research and revolutionary knowledge.”

We of the shadow panel have divided up the longlist titles between us as follows (though we may well each get hold of and read more of the books, simply out of personal interest) and will post reviews on our blogs within the next five weeks.

Amateur: A true story about what makes a man by Thomas Page McBee – LAURA

Astroturf by Matthew Sperling – PAUL

Educated by Tara Westover – CLARE

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi – REBECCA

Heart: A history by Sandeep Jauhar – LAURA

Mind on Fire: A memoir of madness and recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning – REBECCA

Murmur by Will Eaves – PAUL

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh – CLARE

Polio: The odyssey of eradication by Thomas Abraham – ANNABEL

[Sight by Jessie Greengrass – 4 of us have read this; I’ll post a composite of our thoughts]

The Trauma Cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay and disaster by Sarah Krasnostein – ANNABEL

This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein – LAURA

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

Are there any books on here that you’d like to read?

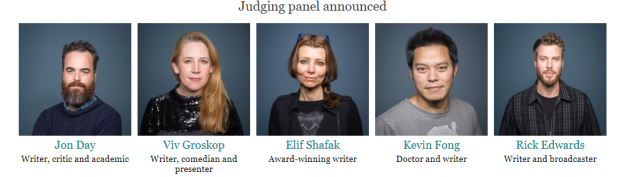

Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz

This intense Argentinian novella, originally published in 2012 and nominated for this year’s Republic of Consciousness and Man Booker International Prizes, is an inside look at postpartum depression as it shades into what looks like full-blown psychosis. We never learn the name of our narrator, just that she’s a foreigner living in France (like Harwicz herself) and has a husband and young son. The stream-of-consciousness chapters are each composed of a single paragraph that stretches over two or more pages. From the first page onwards, we get the sense that this character is on the edge: as she’s hanging laundry outside, she imagines a sun shaft as a knife in her hand. But for now she’s still in control. “I wasn’t going to kill them. I dropped the knife and went to hang out the washing like nothing had happened.”

Not a lot happens over the course of the book; what’s more important is to be immersed in this character’s bitter and perhaps suicidal or sadistic outlook. But there are a handful of concrete events. Her father-in-law has recently died, so she tells of his funeral and what she perceives as his sad little life. Her husband brings home a stray dog that comes to a bad end. Their son attends a children’s party and they take along a box of pastries that melt in the heat.

Not a lot happens over the course of the book; what’s more important is to be immersed in this character’s bitter and perhaps suicidal or sadistic outlook. But there are a handful of concrete events. Her father-in-law has recently died, so she tells of his funeral and what she perceives as his sad little life. Her husband brings home a stray dog that comes to a bad end. Their son attends a children’s party and they take along a box of pastries that melt in the heat.

The only escape from this woman’s mind is a chapter from the point of view of a neighbor, a married radiologist with a disabled daughter who passes her each day on his motorcycle and desires her. With such an unreliable narrator, though, it’s hard to know whether the relationship they strike up is real. This woman is racked by sexual fantasies, but doesn’t seem to be having much sex; when she does, it’s described in disturbing terms: “He opened my legs. He poked around with his calloused hands. Desire is the last thing there is in my cries.”

The language is jolting and in-your-face, but often very imaginative as well. Harwicz has achieved the remarkable feat of showing a mind in the process of cracking up. It’s all very strange and unnerving, and I found that the reading experience required steady concentration. But if you find the passages below intriguing, you’ll want to seek out this top-class translation from new Edinburgh-based publisher Charco Press. It’s the first book in what Harwicz calls “an involuntary trilogy” and has earned her comparisons to Virginia Woolf.

“My mind is somewhere else, like I’ve been startled awake by a nightmare. I want to drive down the road and not stop when I reach the irrigation ditch.”

“I take off my sleep costume, my poisonous skin. I recover my sense of smell and my eyelashes, go back to pronouncing words and swallowing. I look at myself in the mirror and see a different person to yesterday. I’m not a mother.”

“The look I’m going for is Zelda Fitzgerald en route to Switzerland, and not for the chocolate or watches, either.”

My rating:

Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses and Carolina Orloff. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker 12. The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantú: Francisco Cantú was a U.S. Border Patrol agent for four years in Arizona and Texas. Impressionistic rather than journalistic, his book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that, in giving faces to an abstract struggle, argues passionately that people should not be divided by walls but united in common humanity.

12. The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantú: Francisco Cantú was a U.S. Border Patrol agent for four years in Arizona and Texas. Impressionistic rather than journalistic, his book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that, in giving faces to an abstract struggle, argues passionately that people should not be divided by walls but united in common humanity. 11. Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later.

11. Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. 10. Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by the idea that you can claim God’s blessings, financial and otherwise, as a reward for righteous behavior and generosity to the church (“the prosperity gospel”), but if she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future.

10. Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by the idea that you can claim God’s blessings, financial and otherwise, as a reward for righteous behavior and generosity to the church (“the prosperity gospel”), but if she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future. 9. Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman: Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, Altman exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read.

9. Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman: Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, Altman exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. 8. The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014; he approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. This is some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read.

8. The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014; he approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. This is some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. 7. Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine: For Rebecca Loncraine, after treatment for breast cancer in her early thirties, taking flying lessons in an unpowered glider (everywhere from Wales to Nepal) was a way of rediscovering joy and experiencing freedom by facing her fears in the sky. Each year seems to bring one exquisite posthumous memoir about facing death with dignity; this is a worthwhile successor to When Breath Becomes Air et al.

7. Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine: For Rebecca Loncraine, after treatment for breast cancer in her early thirties, taking flying lessons in an unpowered glider (everywhere from Wales to Nepal) was a way of rediscovering joy and experiencing freedom by facing her fears in the sky. Each year seems to bring one exquisite posthumous memoir about facing death with dignity; this is a worthwhile successor to When Breath Becomes Air et al. 6. Face to Face by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more; McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.

6. Face to Face by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more; McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve. 5. That Was When People Started to Worry by Nancy Tucker: Tucker interviewed 70 women aged 16 to 25 for a total of more than 100 hours and chose to anonymize their stories by creating seven composite characters who represent various mental illnesses: depression, bipolar disorder, self-harm, anxiety, eating disorders, PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Reading this has helped me to understand friends’ and acquaintances’ behavior; I’ll keep it on the shelf as an invaluable reference book in the years to come.

5. That Was When People Started to Worry by Nancy Tucker: Tucker interviewed 70 women aged 16 to 25 for a total of more than 100 hours and chose to anonymize their stories by creating seven composite characters who represent various mental illnesses: depression, bipolar disorder, self-harm, anxiety, eating disorders, PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Reading this has helped me to understand friends’ and acquaintances’ behavior; I’ll keep it on the shelf as an invaluable reference book in the years to come. 4. Free Woman by Lara Feigel: A familiarity with the works of Doris Lessing is not a prerequisite to enjoying this richly satisfying hybrid of biography, literary criticism and memoir. Lessing’s The Golden Notebook is about the ways in which women compartmentalize their lives and the struggle to bring various strands into harmony; that’s what Free Woman is all about as well.

4. Free Woman by Lara Feigel: A familiarity with the works of Doris Lessing is not a prerequisite to enjoying this richly satisfying hybrid of biography, literary criticism and memoir. Lessing’s The Golden Notebook is about the ways in which women compartmentalize their lives and the struggle to bring various strands into harmony; that’s what Free Woman is all about as well. 3. Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author endured sexual and psychological abuse while growing up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber – a fascinating, flawed figure – outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 1970s. This is definitely not a boring tome just for architecture buffs; it’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

3. Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author endured sexual and psychological abuse while growing up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber – a fascinating, flawed figure – outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 1970s. This is definitely not a boring tome just for architecture buffs; it’s a masterful memoir for everyone. 2. Educated by Tara Westover: Westover writes with calm authority, channeling the style of the scriptures and history books that were formative in her upbringing and education as she tells of a young woman’s off-grid upbringing in Idaho and the hard work that took her from almost complete ignorance to a Cambridge PhD. This is one of the most powerful and well-written memoirs I’ve ever read.

2. Educated by Tara Westover: Westover writes with calm authority, channeling the style of the scriptures and history books that were formative in her upbringing and education as she tells of a young woman’s off-grid upbringing in Idaho and the hard work that took her from almost complete ignorance to a Cambridge PhD. This is one of the most powerful and well-written memoirs I’ve ever read. 1. Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: A spell-bindingly lyrical book that ranges from literature and geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein. Its every sentence is well-crafted and memorable; this isn’t old-style nature writing in search of unspoiled places, but part of a growing interest in the ‘edgelands’ where human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in.

1. Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: A spell-bindingly lyrical book that ranges from literature and geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein. Its every sentence is well-crafted and memorable; this isn’t old-style nature writing in search of unspoiled places, but part of a growing interest in the ‘edgelands’ where human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in.

These stories overlap with each other – anxiety and depression commonly co-occur with other mental illness, for instance. Yasmine’s bipolar means that sometimes she feels like she could run a marathon or write a novel in a few days, while other times she’s plunged into the depths of depression. Neither Abby (depression) nor Freya (anxiety) can face going to work; Maya (BPD, also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder) exhibits many of the symptoms from other chapters, including self-harm and feelings of emptiness.

These stories overlap with each other – anxiety and depression commonly co-occur with other mental illness, for instance. Yasmine’s bipolar means that sometimes she feels like she could run a marathon or write a novel in a few days, while other times she’s plunged into the depths of depression. Neither Abby (depression) nor Freya (anxiety) can face going to work; Maya (BPD, also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder) exhibits many of the symptoms from other chapters, including self-harm and feelings of emptiness.