Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Hardy’s Wives, Rituals, and Romcoms

Liz is hosting this week of Nonfiction November. For this prompt, the idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with three based on my recent reading:

Thomas Hardy’s Wives

On my pile for Novellas in November was a tiny book I’ve owned for nearly two decades but not read until now. It contains some of the backstory for an excellent historical novel I reviewed earlier in the year.

Some Recollections by Emma Hardy

&

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry

The manuscript of Some Recollections is one of the documents Thomas Hardy found among his first wife’s things after her death in 1912. It is a brief (15,000-word) memoir of her early life from childhood up to her marriage – “My life’s romance now began.” Her middle-class family lived in Plymouth and moved to Cornwall when finances were tight. (Like the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice, you look at the house they lived in, and read about the servants they still employed, and think, “impoverished,” seriously?!) “Though trifling as they may seem to others all these memories are dear to me,” she writes. It’s true that most of these details seem inconsequential, of folk historical value but not particularly illuminating about the individual.

An exception is her account of her dealings with fortune tellers, who often went out of their way to give her good – and accurate – predictions, such as that she would marry a writer. It’s interesting to set this occult belief against the traditional Christian faith she espouses in her concluding paragraph, in which she insists an “Unseen Power of great benevolence directs my ways.” The other point of interest is her description of her first meeting with Hardy, who was sent to St. Juliot, where she was living with her parson brother-in-law and sister, as an architect’s assistant to begin repairs on the church. “I thought him much older than he was,” she wrote. As editor Robert Gittings notes, Hardy made corrections to the manuscript and in some places also changed the sense. Here Hardy gave proof of an old man’s continued vanity by adding “he being tired” after that line … but then partially rubbing it out. (Secondhand, Books for Amnesty, Reading, 2004) [64 pages]

The Chosen contrasts Emma’s idyllic mini memoir with her bitterly honest journals – Hardy read but then burned these, so Lowry had to recreate their entries based on letters and tone. But Some Recollections went on to influence his own autobiography, and to be published in a stand-alone volume by Oxford University Press. Gittings introduces the manuscript (complete with Emma’s misspellings and missing punctuation) and appends a selection of Hardy’s late poems based on his first marriage – this verse, too, is central to The Chosen.

Another recent nonfiction release on this subject matter that I learned about from a Shiny New Books review is Woman Much Missed: Thomas Hardy, Emma Hardy and Poetry by Mark Ford. I’d also like to read the forthcoming Hardy Women: Mother, Sisters, Wives, Muses by Paula Byrne (1 February 2024, William Collins).

Rituals

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton

&

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts

Last month I reviewed this lovely Welsh novel about a woman who is an independent celebrant, helping people celebrate landmark events in their lives or cope with devastating losses by commemorating them through secular rituals.

Coming out in April 2024, The Ritual Effect is a Harvard Business School behavioral scientist’s wide-ranging study of how rituals differ from habits in that they are emotionally charged and lift everyday life into something special. Some of his topics are rites of passage in different cultures; musicians’ and sportspeople’s pre-performance routines; and the rituals we develop around food and drink, especially at the holidays. I’m just over halfway through this for an early Shelf Awareness review and I have been finding it fascinating.

Romantic Comedy

(As also featured in my August Six Degrees post)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman

&

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Romantic Comedy is probably still the most fun reading experience I’ve had this year. Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding is a lighthearted record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. (Newman even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s “Danny Horst Rule”: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”) Unfortunately, it got repetitive and raunchy. It was one of my 20 Books of Summer but I DNFed it halfway.

Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

This Austrian novella, originally published in German in 2020, also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal. It is Helfer’s fourth book but first to become available in English translation. I picked it up on a whim from a charity shop.

“Memory has to be seen as utter chaos. Only when a drama is made out of it is some kind of order established.”

A family saga in miniature, this has the feel of a family memoir, with the author frequently interjecting to say what happened later or who a certain character would become, yet the focus on climactic scenes – reimagined through interviews with her Aunt Kathe – gives it the shape of autofiction.

Josef and Maria Moosbrugger live on the outskirts of an alpine village with their four children. The book’s German title, Die Bagage, literally means baggage or bearers (Josef’s ancestors were itinerant labourers), but with the connotation of riff-raff, it is applied as an unkind nickname to the impoverished family. When Josef is called up to fight in the First World War, life turns perilous for the beautiful Maria. Rumours spread about her entertaining men up at their remote cottage, such that Josef doubts the parentage of the next child (Grete, Helfer’s mother) conceived during one of his short periods of leave. Son Lorenz resorts to stealing food, and has to defend his mother against the mayor’s advances with a shotgun.

If you look closely at the cover, you’ll see it’s peopled with figures from Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games. Helfer was captivated by the thought of her mother and aunts and uncles as carefree children at play. And despite the challenges and deprivations of the war years, you do get the sense that this was a joyful family. But I wondered if the threats were too easily defused. They were never going to starve because others brought them food; the fending-off-the-mayor scenes are played for laughs even though he very well could have raped Maria.

Helfer’s asides (“But I am getting ahead of myself”) draw attention to how she took this trove of family stories and turned them into a narrative. I found that the meta moments interrupted the flow and made me less involved in the plot because I was unconvinced that the characters really did and said what she posits. In short, I would probably have preferred either a straightforward novella inspired by wartime family history, or a short family memoir with photographs, rather than this betwixt-and-between document.

(Bloomsbury, 2023. Translated from the German by Gillian Davidson. Secondhand purchase from Bas Books and Home, Newbury.) [175 pages]

20 Books of Summer, 5: Crudo by Olivia Laing (2018)

Behind on the challenge, as ever, I picked up a novella. It vaguely fits with a food theme as crudo, “raw” in Italian, can refer to fish or meat platters (depicted on the original hardback cover). In this context, though, it connotes the raw material of a life: a messy matrix of choices and random happenings, rooted in a particular moment in time.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

For as hyper-real as the contents are, Laing is doing something experimental, even fantastical – blending biography with autofiction and cultural commentary by making her main character, apparently, Kathy Acker. Never mind that Acker died of breast cancer in 1997.

I knew nothing of Acker but – while this is clearly born of deep admiration, as well as familiarity with her every written word – that didn’t matter. Acker quotes and Trump tweets are inserted verbatim, with the sources given in a “Something Borrowed” section at the end.

Like Jenny Offill’s Weather, this is a wry and all too relatable take on current events and the average person’s hypocrisy and sense of helplessness, with the lack of speech marks and shortage of punctuation I’ve come to expect from ultramodern novels:

she might as well continue with her small and cultivated life, pick the dahlias, stake the ones that had fallen down, she’d always known whatever it was wasn’t going to last for long.

40, not a bad run in the history of human existence but she’d really rather it all kept going, water in the taps, whales in the oceans, fruits and duvets, the whole sumptuous parade

This is how it is then, walking backwards into disaster, braying all the way.

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

Literary Wives Club: The Harpy by Megan Hunter

(My fifth read with the Literary Wives online book club; see also Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews.)

Megan Hunter’s second novella, The Harpy (2020), treads familiar ground – a wife discovers evidence of her husband’s affair and questions everything about their life together – but somehow manages to feel fresh because of the mythological allusions and the hint of how female rage might reverse familial patterns of abuse.

Lucy Stevenson is a mother of two whose husband Jake works at a university. One day she opens a voicemail message on her phone from a David Holmes, saying that he thinks Jake is having an affair with his wife, Vanessa. Lucy vaguely remembers meeting the fiftysomething couple, colleagues of Jake’s, at the Christmas party she hosted the year before.

As further confirmation arrives and Lucy tries to carry on with everyday life (another Christmas party, a pirate-themed birthday party for their younger son), she feels herself transforming into a wrathful, ravenous creature – much like the harpies she was obsessed with as a child and as a Classics student before she gave up on her PhD.

Like the mythical harpy, Lucy administers punishment. At first, it’s something of a joke between her and Jake: he offers that she can ritually harm him three times. Twice it takes physical form; once it’s more about reputational damage. The third time, it goes farther than either of them expected. It’s clever how Hunter presents this formalized violence as an inversion of the domestic abuse of which Lucy’s mother was a victim.

Lucy also expresses anger at how women are objectified, and compares three female generations of her family in terms of how housewifely duties were embraced or rejected. She likens the grief she feels over her crumbling marriage to contractions or menstrual cramps. It’s overall a very female text, in the vein of A Ghost in the Throat. You feel that there’s a solidarity across time and space of wronged women getting their own back. I enjoyed this so much more than Hunter’s debut, The End We Start From. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

“Marriage and motherhood are like death … no one comes back unchanged.”

So much in life can remain unspoken, even in a relationship as intimate as a marriage. What becomes routine can cover over any number of secrets; hurts can be harboured until they fuel revenge. Lucy has lost her separate identity outside of her family relationships and needs to claw back a sense of self.

I don’t know that this book said much that is original about infidelity, but I sympathized with Lucy’s predicament. The literary and magical touches obscure the facts of the ending, so it’s unclear whether she’ll stay with Jake or not. Because we’re mired in her perspective, it’s hard to see Jake or Vanessa clearly. Our only choice is to side with Lucy.

Next book: Sea Wife by Amity Gaige in September

From the Dylan Thomas Prize Shortlist: Seven Steeples & I’m a Fan

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so the shortlist contains a poetry collection as well as novels and short stories.

I’ve read half of the shortlist (also including Warsan Shire’s poems) and would be interested in trying the rest if I can source the two short story collections; Limberlost is at my library. The winner will be announced at 8 p.m. BST on Thursday 11 May.

Seven Steeples by Sara Baume

Isabel and Simon arrive one January at a shabby rental house in coastal Ireland overlooked by a mountain, in the middle of nowhere. They’d been menial workers in Dublin and met climbing a mountain, but somehow never seem to get around to climbing their new local peak. In moving here, these “two solitary misanthropes” are essentially rejecting society and kin; Baume describes them as “post-family.” It appears that they’re post-employment as well – there is never a single reference to how they pay the rent and buy the hipster foods they favour. Could young people’s savings really fund eight years’ rural living?

It’s an appealingly anti-consumerist vision, anyway: They arrive with one van-load of stuff and their adopted dogs, Pip and Voss, and otherwise make do with a haphazard collection of secondhand belongings left by previous tenants or donated by their estranged families. The house starts to fall apart around them, but for the most part they adjust to the decay rather than do anything to reverse it. “They had become poor and shabby without noticing … accustomed to disrepair”; theirs is a “personalized squalor.”

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

I recognized from Spill Simmer Falter Wither and handiwork several elements that reflect Baume’s interests: nature imagery, dogs, and daily routines. She gives a clear sense of time’s passage and the seasons’ turning, of repetition and attrition and ageing. I wearied of the descriptive passages and hoped that at some point there would be some action and dialogue to counterbalance them, but that is not what this novel is about. Occasional flashes from the point-of-view of a mouse in the house, or a spider in the van, tell you that Baume’s scope is wider. This is in fact an allegory about impermanence, from a mountain’s-eye view.

Although I was frustrated with the central characters’ jolly incompetence (“Just buy leashes and a tick twister, you idiots!” I felt like shouting at them after yet another mention of the dogs killing cats and rabbits; and of the difficulty of removing ticks from their coats), I recognized how easy it is to get stuck in lazy habits; how easy it is to live provisionally, as if all is temporary and not your real existence.

Baume spaces lines and paragraphs almost like hybrid poetry and indulges in overwriting in places. Because of the dearth of action, this was a slog of a months-long read for me, but I admired it in the end and enjoyed it more than the other two books of hers that I’ve read.

If you admire lyrical prose and are okay with little to no plot in a novel, you should get on fine with this one. Or it might be that it requires the right time or reading mood, when you’re after something quiet.

Having read more by Dylan Thomas now, I think this is exactly the sort of place-specific and playful, stylized prose that the prize named after him is looking for. So, I’ll predict Baume as the winner.

With thanks to Tramp Press for the free e-copy for review.

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

This was one of my correct predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist; I’d heard a lot about it from Best of 2022 roundups and it seemed like the kind of edgy title they might recognise. It’s also perfect for the Dylan Thomas Prize list because of how voice-driven it is. The unnamed narrator, a woman of colour in her early thirties, muses on art, entitlement, obsession, social media and sex in short titled sections ranging from one paragraph to a few pages long. The twin objects of her fanaticism are “the man I want to be with,” who is married and generally keeps her at arm’s length, and “the woman I am obsessed with,” a lifestyle influencer who, like herself, is one of this man’s girlfriends on the side. She stalks the woman via her impeccably curated Instagram images.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

She reminded me a bit of Bell and Sigh for her haplessness, but whereas the matter of having children literally never arises for them, the question of motherhood is a background niggle for her (“I thought I had the rest of my life to make this decision but I realise I am on a clock and it runs differently for me. I am female. There was never much time and I’ve wasted so much already”; “I want to gain immortality because of my brain and not because of the potential of my womb”). As the novella goes on, she even considers weaponising her fertility as a way of entrapping her crush.

I was reasonably engaged with the narrator’s deliberations about taste and autobiographical influences, but overall found this rather indulgent, slight and repetitive. Books about social media – this reminded me most of Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth – are in danger of becoming irrelevant all too quickly. The sexual frankness fell on the wrong side of unpleasant for me, and the format for referring to other characters leads to inelegant phrasing like “The man I want to be with’s work centres around conflict”. Something like Luster has that little bit more individuality and energy. (Secondhand – charity shop purchase)

February Releases by Nick Acheson, Charlotte Eichler and Nona Fernández (#ReadIndies)

Three final selections for Read Indies. I’m pleased to have featured 16 books from independent publishers this month. And how’s this for neat symmetry? I started the month with Chase of the Wild Goose and finish with a literal wild goose chase as Nick Acheson tracks down Norfolk’s flocks in the lockdown winter of 2020–21. Also appearing today are nature- and travel-filled poems and a hybrid memoir about Chilean and family history.

The Meaning of Geese: A thousand miles in search of home by Nick Acheson

I saw Nick Acheson speak at New Networks for Nature 2021 as the ‘anti-’ voice in a debate on ecotourism. He was a wildlife guide in South America and Africa for more than a decade before, waking up to the enormity of the climate crisis, he vowed never to fly again. Now he mostly stays close to home in North Norfolk, where he grew up and where generations of his family have lived and farmed, working for Norfolk Wildlife Trust and appreciating the flora and fauna on his doorstep.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

The Covid-19 lockdowns spawned a number of nature books in the UK – for instance, I’ve also read Goshawk Summer by James Aldred, Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt, The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, and Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss – and although the pandemic is not a major element here, one does get a sense of how Acheson struggled with isolation as well as the normal winter blues and found comfort and purpose in birdwatching.

Tundra bean, taiga bean, brent … I don’t think I’ve seen any of these species – not even pinkfeet, to my recollection – so wished for black-and-white drawings or colour photographs in the book. That’s not to say that Acheson is not successful at painting word pictures of geese; his rich descriptions, full of food-related and sartorial metaphors, are proof of how much he revels in the company of birds. But I suspect this is a book more for birders than for casual nature-watchers like myself. I would have welcomed more autobiographical material, and Wintering by Stephen Rutt seems the more suitable geese book for laymen. Still, I admire Acheson’s fervour: “I watch birds not to add them to a list of species seen; nor to sneer at birds which are not truly wild. I watch them because they are magnificent”.

With thanks to Chelsea Green Publishing for the free copy for review.

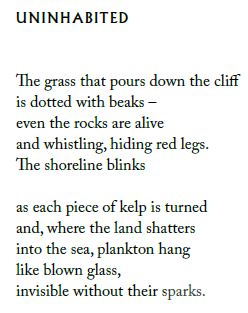

Swimming Between Islands by Charlotte Eichler

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Voyager: Constellations of Memory—A Memoir by Nona Fernández (2019; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer]

Our archive of memories is the closest thing we have to a record of identity. … Disjointed fragments, a pile of mirror shards, a heap of the past. The accumulation is what we’re made of.

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

With thanks to Daunt Books for the free copy for review.

Body Kintsugi by Senka Marić: A Peirene Press Novella (#NovNov22)

This is my eleventh translated novella from Peirene Press* and, in my opinion, their best yet. It’s an intense work of autofiction about two years of hellish treatment for breast cancer, all the more powerful due to the second-person narration that displaces the pain from the protagonist and onto the reader.

This is a story about the body. Its struggle to feel whole while reality shatters it into fragments. The gash goes from the right nipple towards your back, and after five centimetres makes a gentle curve up and continues to your armpit. It’s still fresh and red.

How does the story crumbling under your tongue and refusing to take on a firm shape begin to be told?

You knew on that day, sixteen years ago, when your mother’s diagnosis was confirmed, that you’d get cancer?

Or

Ever since that day, sixteen years ago, when your mother’s diagnosis was confirmed, that you’d never get cancer?

Both are equally true.

In 2014, just a couple of months after her husband leaves her – making her, in her early forties, a single mother to a son and a daughter – she discovers a lump in her right breast.

In 2014, just a couple of months after her husband leaves her – making her, in her early forties, a single mother to a son and a daughter – she discovers a lump in her right breast.

As she endures five operations, chemotherapy and adjuvant therapies, as well as endless testing and hospital stays, her mind keeps going back to her girlhood and adolescence, especially the moments when she felt afraid or ashamed. Her father, alcoholic and perpetually ill, made her feel like she was an annoyance to him.

Coming of age in a female body was traumatic in itself; now that same body threatens to kill her. Even as she loses the physical signs of femininity, she remains resilient. Her body will document what she’s been through: “Perfectly sculpted through all your defeats, and your victories. The scars scrawled on it are the map of your journey. The truest story about you, which words cannot grasp.”

As forthright as it is about the brutality of cancer treatment, the novella can also be creative, playful and even darkly comic.

Things you don’t want to think about:

Your children

Your boobs

Your cancer

Your bald head

Your death

Almost unbearable nausea delivers her into a new space: “Here, the only colours are black and red. You’re lost in a vast hotel. However hard you try, you can’t count the floors.” One snowy morning, she imagines she’s being visited by a host of Medusa-like women in long black dresses who minister to her. Whether it’s a dream or a medication-induced hallucination, it feels mystical, like she’s part of a timeless lineage of wise women. The themes, tone and style all came together here for me, though I can see how this book might not be for everyone. I have a college friend who’s going through breast cancer treatment right now. She’s only 40. She was diagnosed in the summer and has already had surgery and a few rounds of chemo. I wonder if this book is just what she would want to read right now … or the last thing she would want to think about. All I can do is ask.

(Translated from the Bosnian by Celia Hawkesworth) [165 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

*Other Peirene Press novellas I’ve reviewed:

Mr. Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson

The Looking-Glass Sisters by Gøhril Gabrielsen

Ankomst by Gøhril Gabrielsen

Dance by the Canal by Kerstin Hensel

The Last Summer by Ricarda Huch

Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini

Her Father’s Daughter by Marie Sizun

The Orange Grove by Larry Tremblay

The Man I Became by Peter Verhelst

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession.

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession. Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)  The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress.

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress.

Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of

Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of  The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.

The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.  A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.

A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.  Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.

Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.  The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.

The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.  Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.

Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.  Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.

Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.  Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.

Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.  The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.  The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a