Love Your Library, October 2022

Naomi has been reading an interesting selection of books from the library. I’ve recently returned a couple of giant piles of library books unread or part-read so that I can focus on novellas next month; I can always borrow those particular books again another time, or maybe the fact that none ever made it onto one of my reading stacks tells me I wasn’t excited enough about them.

A lot of other reading challenges are coming up in November: Australia Reading Month, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month, and Nonfiction November. If you don’t already have plans, your local library is a great source of options. And of course we would be delighted to have you join us in reading one or more short books for Novellas in November (#NovNov22), which launches tomorrow. I’ve been reading ahead for it, as you can see.

Since last month (links where I haven’t already reviewed a book or plan to soon):

READ

- The Improbable Cat by Allan Ahlberg

- Treacle Walker by Alan Garner

- Jungle Nama by Amitav Ghosh

- The Fear Index by Robert Harris

- Hare House by Sally Hinchcliffe

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

- Undoctored by Adam Kay

- Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham

- Metronome by Tom Watson

- Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

CURRENTLY READING

- Strangers on a Pier: Portrait of a Family by Tash Aw

- Heat and Dust by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay

- Leap Year by Helen Russell

Then I have various new releases on hold for me, including the new Maggie O’Farrell novel (which I’m on the fence about actually reading) and this pleasingly colourful pair.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Planning My Reading Stacks for Novellas in November (#NovNov22)

Just a couple of weeks until Novellas in November (#NovNov22) begins! I gathered up all of my potential reads for a photo shoot, including review copies, library loans, recent birthday gifts and books that have been languishing on my shelves for ages.

Week One: Short Classics (= pre-1980)

Week Two: Novellas in Translation

I always struggle with this prompt the most. (The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang Goethe would also be a token contribution to German Literature Month.)

I always struggle with this prompt the most. (The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang Goethe would also be a token contribution to German Literature Month.)

Week Three: Short Nonfiction

This is probably (not so secretly) my favourite week of the month. Others may find it strange to consider nonfiction during a novellas month, but this challenge is really about celebrating the art of the short book in all its forms, and I love a work that can contribute something significant on a topic, or illuminate a portion of an author’s life, in under 200 pages.

This is probably (not so secretly) my favourite week of the month. Others may find it strange to consider nonfiction during a novellas month, but this challenge is really about celebrating the art of the short book in all its forms, and I love a work that can contribute something significant on a topic, or illuminate a portion of an author’s life, in under 200 pages.

Week Four: Contemporary Novellas (= post-1980)

I have a few other options on my e-readers as well, such as Marigold and Rose by Louise Glück, Foster by Claire Keegan (our buddy read for the month), and The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken.

I read 29 novellas last November; why not aim for one a day this time?! November is also Margaret Atwood Reading Month, so I’ve lined up one of her fairly recent poetry collections that I picked up from a Little Free Library. Apart from that, I do have a few review books I need to get to for Shelf Awareness, so it’ll be a jam-packed month.

Kate has already come up with her list of possible titles. Look out for Cathy’s today, too. If you’re struggling for ideas, here’s a long list of suitable authors and publishers I put together last year, or you might like to browse through the reviews from 2021.

Now to get reading!!

Do you have any novellas in mind to read next month?

Which options from my stacks should I prioritize?

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler” (said Joe Hill). For the third year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long challenge, with four weekly prompts we’ll take it in turns to focus on. We’re announcing early to give you plenty of time to get your stacks ready.

Here’s the schedule:

1–7 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

8–14 November: Novellas in translation (Cathy)

15–21 November: Short nonfiction (Rebecca)

22–28 November: Contemporary novellas (Cathy)

29–30 November: You might like to post a “New to my TBR” or “My NovNov Month” roundup.

(As a reminder, we suggest 150–200 pages as the upper limit for a novella, and post-1980 as a definition of “contemporary.”)

This year we have one overall buddy read. Claire Keegan has experienced a resurgence of attention thanks to the Booker Prize shortlisting of Small Things Like These – one of our most-reviewed novellas from last year. Foster is a modern Irish classic that comes in at under 90 pages, and, in an abridged version, is free to read on the New Yorker website. You can find that here. (Or whet your appetite with Cathy’s review.)

Keegan describes Foster as a “long short story” rather than a novella, but it was published as a standalone volume by Faber in 2010. A new edition will be released by Grove Press in the USA on November 1st, and the book is widely available for Kindle. It is also the source material for the recent record-breaking Irish-language film The Quiet Girl, so there are several ways for you to encounter this story.

We’re looking forward to having you join us! We will each put up a pinned post where you can leave links starting on 1 November. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made and our new hashtag, #NovNov22.

Novellas in November Wrap-Up

Last year, our first of hosting Novellas in November as an official blogger challenge, we had 89 posts by 30 bloggers. This year, Cathy and I have been simply blown away by the level of participation: as of this afternoon, our count is that 49 bloggers have taken part, publishing just over 200 posts and covering over 270 books. We’ve done our best to keep up with the posts, which we’ve each been collecting as links on the opening master post. (Here’s mine.)

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov, including with the buddy reads we tried out for the first time this year. We’re already thinking about changes we might implement for next year.

A special mention goes to Simon of Stuck in a Book for being such a star supporter and managing to review a novella on most days of the month.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Some authors who were reviewed more than once (highlighting different works) were Margaret Atwood, Henry James, Elizabeth Jolley, Amos Oz, George Simenon, and Muriel Spark.

Of course, novellas are great to read the whole year round and not just in November, but we hope this has been a good excuse to pick up some short books and appreciate how much can be achieved with such a limited number of pages. If we missed any of your coverage, let us know and we will gladly add it in to the master list.

See you next year!

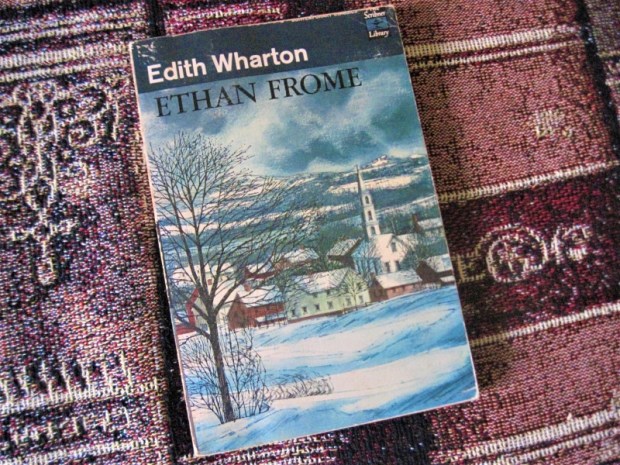

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (#NovNov Classics Week Buddy Read)

For the short classics week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (1911). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Did you have to read Ethan Frome in school? For American readers, it’s likely that it was an assigned text in high school English. I didn’t happen to read it during my school days, but caught up in 2006 or 2008, I think, and was impressed with this condensed tragedy and the ambiance of a harsh New England winter. It struck me even more on a reread as a flawless parable of a man imprisoned by circumstance and punished for wanting more.

I had forgotten that the novella is presented as a part-imagined reconstruction of the sad events of Ethan Frome’s earlier life. A quarter-century later, the unnamed narrator is in Wharton’s fictional Starkfield, Massachusetts on business, and hears the bare bones of Ethan’s story from various villagers before meeting the man himself. Ethan, who owns a struggling sawmill, picks up extra money from odd jobs. He agrees to chauffeur the narrator to engineering projects in his sleigh, and can’t conceal his jealousy at a technical career full of travel – a reminder of what could have been had he been able to continue his own scientific studies. A blizzard forces the narrator to stay overnight in Ethan’s home, and the step over the threshold sends readers back in time to when Ethan was a young man of 28.

*There are SPOILERS in the following.*

Ethan’s household contains two very different women: his invalid wife, Zeena, eight years his elder; and her cousin, Mattie Silver, who serves as her companion and housekeeper. Mattie is dreamy and scatter-brained – not the practical sort you’d want in a carer role, but she had nowhere else to go after her parents’ death. She has become the light of Ethan’s life. By contrast, Zeena is shrewish, selfish, lazy and gluttonous. Wharton portrays her as either pretending or exaggerating about her chronic illness. Zeena has noticed that Ethan has taken extra pains with his appearance in the year since Mattie came to live with them, and conspires to get rid of Mattie by getting a new doctor to ‘prescribe’ her a full-time servant.

The plot turns on an amusing prop, “Aunt Philura Maple’s pickle-dish.” While Zeena is away for her consultation with Dr. Buck, Ethan and Mattie get one evening alone together. Mattie lays the table nicely with Zeena’s best dishes from the china cabinet, but at the end of their meal the naughty cat gets onto the table and knocks the red glass pickle dish to the floor, where it smashes. Before Ethan can obtain glue to repair it in secret, Zeena notices and acts as if this never-used dish was her most prized possession. She and Ethan are both to have what they most love taken away from them – but at least Ethan’s is a human being.

I had remembered that Ethan fell in love with a cousin (though I thought it was his cousin) and that there is a dramatic sledding accident. What I did not remember, however, was that the crash is deliberate: knowing they can never act on their love for each other, Mattie begs Ethan to steer them straight into the elm tree mentioned twice earlier. He dutifully does so. I thought I recalled that Mattie dies, while he has to live out his grief ever more. I was gearing myself up to rail against the lingering Victorian mores of the time that required the would-be sexually transgressing female to face the greatest penalty. Instead, in the last handful of pages, Wharton delivers a surprise. When the narrator enters the Frome household, he meets two women. One is chair-bound and sour; the other, tall and capable, bustles about getting dinner ready. The big reveal, and horrible irony, is that the disabled woman is Mattie, made bitter by suffering, while Zeena rose to the challenges of caregiving.

Ethan is a Job-like figure who lost everything that mattered most to him, including his hopes for the future. Unlike the biblical character, though, he finds no later reward. “Sickness and trouble: that’s what Ethan’s had his plate full up with, ever since the very first helping,” as one of the villagers tells the narrator. “He looks as if he was dead and in hell now!” the narrator observes. This man of sorrow is somehow still admirable: he and Zeena did the right thing in taking Mattie in again, and even when at his most desperate Ethan refused to swindle his customers to fund an escape with Mattie. In the end, Mattie’s situation is almost the hardest to bear: she only ever represented sweetness and love, and has the toughest lot. In some world literature, e.g. the Russian masters, suicide might be rendered noble, but here its attempt warrants punishment.

{END OF SPOILERS.}

I can see why some readers, especially if encountering this in a classroom setting, would be turned off by the bleak picture of how the universe works. But I love me a good classical tragedy, and admired this one for its neat construction, its clever use of foreshadowing and dread, its exploration of ironies, and its use of a rustic New England setting – so much more accessible than Wharton’s usual New York City high society. The cozy wintry atmosphere of Little Women cedes to something darker and more oppressive; “Guess he’s been in Starkfield too many winters,” a neighbor observes of Ethan. I could see a straight line from Jude the Obscure through Ethan Frome to The Great Gatsby: three stories of an ordinary, poor man who pays the price for grasping for more. I reread this in two sittings yesterday morning and it felt to me like a perfect example of how literature can encapsulate the human condition.

(Secondhand purchase) [181 pages]

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), using the hashtag #NovNov. We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts.

#NovNov Translated Week: In the Company of Men and Winter Flowers

I’m sneaking in under the wire here with a couple more reviews for the literature in translation week of Novellas in November. These both happen to be translated from the French, and attracted me for their medical themes: the one ponders the Ebola crisis in Africa, and the other presents a soldier who returns from war with disfiguring facial injuries.

In the Company of Men: The Ebola Tales by Véronique Tadjo (2017; 2021)

[Translated from the French by the author and John Cullen; Small Axes Press; 133 pages]

This creative and compassionate work takes on various personae to plot the course of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–16: a doctor, a nurse, a morgue worker, bereaved family members and browbeaten survivors. The suffering is immense, and there are ironic situations that only compound the tragedy: the funeral of a traditional medicine woman became a super-spreader event; those who survive are shunned by their family members. Tadjo flows freely between all the first-person voices, even including non-human narrators such as baobab trees and the fruit bat in which the virus likely originated (then spreading to humans via the consumption of the so-called bush meat). Local legends and songs, along with a few of her own poems, also enter into the text.

This creative and compassionate work takes on various personae to plot the course of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–16: a doctor, a nurse, a morgue worker, bereaved family members and browbeaten survivors. The suffering is immense, and there are ironic situations that only compound the tragedy: the funeral of a traditional medicine woman became a super-spreader event; those who survive are shunned by their family members. Tadjo flows freely between all the first-person voices, even including non-human narrators such as baobab trees and the fruit bat in which the virus likely originated (then spreading to humans via the consumption of the so-called bush meat). Local legends and songs, along with a few of her own poems, also enter into the text.

Like I said about The Appointment, this would make a really interesting play because it is so voice-driven and each character epitomizes a different facet of a collective experience. Of course, I couldn’t help but think of the parallels with Covid – “you have to keep your distance from other people, stay at home, and wash your hands with disinfectant before entering a public space” – none of which could have been in the author’s mind when this was first composed. Let’s hope we’ll soon be able to join in cries similar to “It’s over! It’s over! … Death has brushed past us, but we have survived! Bye-bye, Ebola!” (Secondhand purchase)

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve (2014; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Adriana Hunter; 172 pages]

With Remembrance Day not long past, it’s been the perfect time to read this story of a family reunited at the close of the First World War. Jeanne Caillet makes paper flowers to adorn ladies’ hats – pinpricks of colour to brighten up harsh winters. Since her husband Toussaint left for the war, it’s been her and their daughter Léonie in their little Paris room. Luckily, Jeanne’s best friend Sidonie, an older seamstress, lives just across the hall. When Toussaint returns in October 1918, it isn’t the rapturous homecoming they expected. He’s been in the facial injuries department at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital, and wrote to Jeanne, “I want you not to come.” He wears a white mask over his face, hasn’t regained the power of speech, and isn’t ready for his wife to see his new appearance. Their journey back to each other is at the heart of the novella, the first of Villeneuve’s works to appear in English.

With Remembrance Day not long past, it’s been the perfect time to read this story of a family reunited at the close of the First World War. Jeanne Caillet makes paper flowers to adorn ladies’ hats – pinpricks of colour to brighten up harsh winters. Since her husband Toussaint left for the war, it’s been her and their daughter Léonie in their little Paris room. Luckily, Jeanne’s best friend Sidonie, an older seamstress, lives just across the hall. When Toussaint returns in October 1918, it isn’t the rapturous homecoming they expected. He’s been in the facial injuries department at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital, and wrote to Jeanne, “I want you not to come.” He wears a white mask over his face, hasn’t regained the power of speech, and isn’t ready for his wife to see his new appearance. Their journey back to each other is at the heart of the novella, the first of Villeneuve’s works to appear in English.

I loved the chapters that zero in on Jeanne’s handiwork and on Toussaint’s injury and recovery (Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Butchering Art, is currently writing a book on early plastic surgery; I’ve heard it also plays a major role in Louisa Young’s My Dear, I Wanted to Tell You – both nominated for the Wellcome Book Prize), and the two gorgeous “Word is…” litanies – one pictured below – but found the book as a whole somewhat meandering and quiet. If you’re keen on the time period and have enjoyed novels like Birdsong and The Winter Soldier, it would be a safe bet. (Cathy’s reviewed this one, too.)

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

(In a nice connection with a previous week’s buddy read, Villeneuve’s most recent novel is about Helen Keller’s mother and is called La Belle Lumière (“The Beautiful Light”). I hope it will also be made available in English translation.)

#NovNov and #GermanLitMonth: The Pigeon and The Appointment

As literature in translation week of Novellas in November continues, I’m making a token contribution to German Literature Month as well. I’m aware that my second title doesn’t technically count towards the challenge because it was originally written in English, but the author is German, so I’m adding it in as a bonus. Both novellas feature an insular perspective and an unusual protagonist whose actions may be slightly difficult to sympathize with.

The Pigeon by Patrick Süskind (1987; 1988)

[Translated from the German by John E. Woods; 77 pages]

At the time the pigeon affair overtook him, unhinging his life from one day to the next, Jonathan Noel, already past fifty, could look back over a good twenty-year period of total uneventfulness and would never have expected anything of importance could ever overtake him again – other than death some day. And that was perfectly all right with him. For he was not fond of events, and hated outright those that rattled his inner equilibrium and made a muddle of the external arrangements of life.

What a perfect opening paragraph! Taking place over about 24 hours in August 1984, this is the odd little tale of a man in Paris who’s happily set in his ways until an unexpected encounter upends his routines. Every day he goes to work as a bank security guard and then returns to his rented room, which he’s planning to buy from his landlady. But on this particular morning he finds a pigeon not a foot from his door, and droppings all over the corridor. Now, I love birds, so this was somewhat difficult for me to understand, but I know that bird phobia is a real thing. Jonathan is so freaked out that he immediately decamps to a hotel, and his day just keeps getting worse from there, in comical ways, until it seems he might do something drastic. The pigeon is both real and a symbol of irrational fears. The conclusion is fairly open-ended, leaving me feeling like this was a short story or unfinished novella. It was intriguing but also frustrating in that sense. There’s an amazing description of a meal, though! (University library)

What a perfect opening paragraph! Taking place over about 24 hours in August 1984, this is the odd little tale of a man in Paris who’s happily set in his ways until an unexpected encounter upends his routines. Every day he goes to work as a bank security guard and then returns to his rented room, which he’s planning to buy from his landlady. But on this particular morning he finds a pigeon not a foot from his door, and droppings all over the corridor. Now, I love birds, so this was somewhat difficult for me to understand, but I know that bird phobia is a real thing. Jonathan is so freaked out that he immediately decamps to a hotel, and his day just keeps getting worse from there, in comical ways, until it seems he might do something drastic. The pigeon is both real and a symbol of irrational fears. The conclusion is fairly open-ended, leaving me feeling like this was a short story or unfinished novella. It was intriguing but also frustrating in that sense. There’s an amazing description of a meal, though! (University library)

(Also reviewed by Cathy and Naomi.)

The Appointment by Katharina Volckmer (2020)

[96 pages]

This debut novella was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize – a mark of experimental style that would often scare me off, so I’m glad I gave it a try anyway. It’s an extended monologue given by a young German woman during her consultation with a Dr Seligman in London. As she unburdens herself about her childhood, her relationships, and her gender dysphoria, you initially assume Seligman is her Freudian therapist, but Volckmer has a delicious trick up her sleeve. A glance at the titles and covers of foreign editions, or even the subtitle of this Fitzcarraldo Editions paperback, would give the game away, so I recommend reading as little as possible about the book before opening it up. The narrator has some awfully peculiar opinions, especially in relation to Nazism (the good doctor being a Jew), but the deeper we get into her past the more we see where her determination to change her life comes from. This was outrageous and hilarious in equal measure, and great fun to read. I’d love to see someone turn it into a one-act play. (New purchase)

This debut novella was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize – a mark of experimental style that would often scare me off, so I’m glad I gave it a try anyway. It’s an extended monologue given by a young German woman during her consultation with a Dr Seligman in London. As she unburdens herself about her childhood, her relationships, and her gender dysphoria, you initially assume Seligman is her Freudian therapist, but Volckmer has a delicious trick up her sleeve. A glance at the titles and covers of foreign editions, or even the subtitle of this Fitzcarraldo Editions paperback, would give the game away, so I recommend reading as little as possible about the book before opening it up. The narrator has some awfully peculiar opinions, especially in relation to Nazism (the good doctor being a Jew), but the deeper we get into her past the more we see where her determination to change her life comes from. This was outrageous and hilarious in equal measure, and great fun to read. I’d love to see someone turn it into a one-act play. (New purchase)

A favourite passage:

But then we are most passionate when we worship the things that don’t exist, like race, or money, or God, or, quite simply, our fathers. God, of course, was a man too. A father who could see everything, from whom you couldn’t even hide in the toilet, and who was always angry. He probably had a penis the size of a cigarette.

I reviewed

I reviewed  A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)  This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s  After reviewing Josipovici’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s  Otsuka’s

Otsuka’s  I could have included this in a translated literature post, but decided to go by theme instead; I also considered reviewing it during nonfiction week as I thought it was a brief memoir. As it turns out, it’s a whimsical tale I’d be more likely to classify under fiction. Barbery has four Chartreux cats – two pairs of siblings: Ocha and Mizu, and Kirin and Petrus. Kirin, one of the younger pair, narrates the book, giving the cats’ view of the writer (and the musician she lives with). They diagnose her as being afflicted with restlessness, doubt and denial, and decide to learn to read so that they can act as literary advisors and comment on her work in progress. Naturally, they’d like to receive royalties for this service. “Yes, we are – in all modesty – decorative, protective deities watching over her rigid little aesthetic world”. Barbery is a Japanophile, so Guitart’s illustrations mix Japanese minimalism with Parisian chic and use as a palette the grey and orange colouring of the cats themselves. This was cute! (Also reviewed by

I could have included this in a translated literature post, but decided to go by theme instead; I also considered reviewing it during nonfiction week as I thought it was a brief memoir. As it turns out, it’s a whimsical tale I’d be more likely to classify under fiction. Barbery has four Chartreux cats – two pairs of siblings: Ocha and Mizu, and Kirin and Petrus. Kirin, one of the younger pair, narrates the book, giving the cats’ view of the writer (and the musician she lives with). They diagnose her as being afflicted with restlessness, doubt and denial, and decide to learn to read so that they can act as literary advisors and comment on her work in progress. Naturally, they’d like to receive royalties for this service. “Yes, we are – in all modesty – decorative, protective deities watching over her rigid little aesthetic world”. Barbery is a Japanophile, so Guitart’s illustrations mix Japanese minimalism with Parisian chic and use as a palette the grey and orange colouring of the cats themselves. This was cute! (Also reviewed by

A tongue-in-cheek book mostly composed of black-and-white cartoons. The “calculating cat” is a bit like Terry Pratchett’s “real cat” from

A tongue-in-cheek book mostly composed of black-and-white cartoons. The “calculating cat” is a bit like Terry Pratchett’s “real cat” from

I’d heard about this via its recent Daunt Books reissue and was attracted to the plague theme. The spark for the story was a real-life event in France in 1951, but Comyns takes imaginative liberties. In 1911, a Warwickshire village is overtaken by calamity: first a flood and then a mysterious sickness. The first line – “The ducks swam through the drawing-room window” – sets up a jolly, fable-like atmosphere as the Willoweed family go rowing through their garden. And yet there’s death all over the place. The multitude of drowned animals soon cedes to a roll call of human casualties. Some deaths are self-inflicted and others result from rapid illness, but all are gruesome. The general pattern of the sickness seems to be stomach pains, fits, bleeding and death, all within a few days. At first, we don’t know if what we’re looking at is a medical phenomenon or a case of mass hysteria. Either is rich fodder for fiction.

I’d heard about this via its recent Daunt Books reissue and was attracted to the plague theme. The spark for the story was a real-life event in France in 1951, but Comyns takes imaginative liberties. In 1911, a Warwickshire village is overtaken by calamity: first a flood and then a mysterious sickness. The first line – “The ducks swam through the drawing-room window” – sets up a jolly, fable-like atmosphere as the Willoweed family go rowing through their garden. And yet there’s death all over the place. The multitude of drowned animals soon cedes to a roll call of human casualties. Some deaths are self-inflicted and others result from rapid illness, but all are gruesome. The general pattern of the sickness seems to be stomach pains, fits, bleeding and death, all within a few days. At first, we don’t know if what we’re looking at is a medical phenomenon or a case of mass hysteria. Either is rich fodder for fiction.