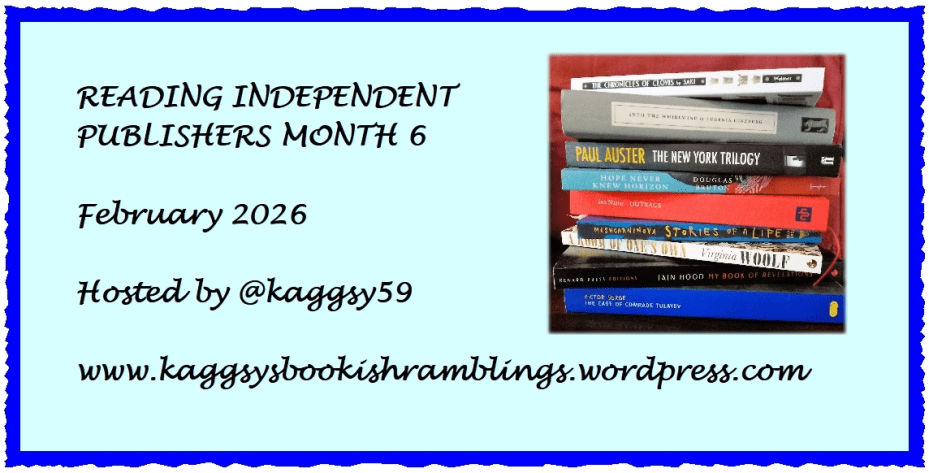

Final Reading Statistics for 2025 & Goals for 2026

Happy New Year! We went to a neighbours’ party again this year and played silly games and chased their kittens until 1:30 a.m. It was a fun, low-key way to see in 2026.

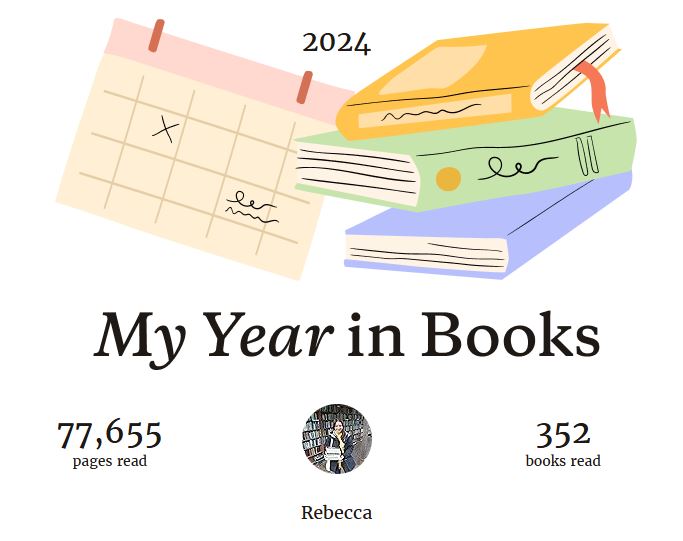

I read 313 books last year. (2024’s total of 352 will never be topped!) Initially, I set a goal of 350, but by midyear I downgraded it to 300 and it was easy to reach. I can’t pinpoint a particular reason for the decline. In general, I felt like I was chasing my tail all year, despite having less work on than ever (but increased volunteering commitments). Often, I struggled with fatigue or being on the verge of illness. What a fun guessing game: is it long Covid or perimenopause?

Goodreads was glitchy for me all year, randomly counting books two or three times and falsely inflating my total by a whole extra 33 books at one point. It also has a lot of annoying, automatically generated book records that duplicate ISBNs or add the publisher to the title field. So I’m thinking about moving over to StoryGraph this year – I just imported my Goodreads library – though I always quail at learning new online systems. It would also be the next logical step in divesting from Am*zon.

The year that was…

2025’s notable happenings:

- Twice assessing the ‘proper’ (published) books as a McKitterick Prize judge

- Adopting crazy Benny (though that was after losing our precious Alfie)

- Acquiring a secondhand electric car for the household

- Holidays in Hay-on-Wye; the Outer Hebrides; Suffolk; Berlin and Lübeck, Germany

- A summer visit from my sister and brother-in-law

- Having the windows and door replaced in the back of our house; and the hall and stairwell/landing redecorated

- I got ever more into gin and cocktails, with tastings in Abingdon and Wantage (and in December I led two informal tastings for friends). I also acquired the taste for rum!

The reading statistics, as compared to 2024:

Fiction: 54.7% (↑3.3%)

Nonfiction: 31.6% (↓0.2%)

Poetry: 13.7% (↓3.1%)

Female author: 67.7% (↓0.2%)

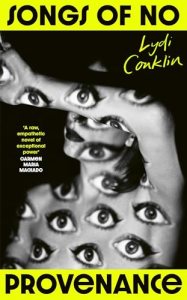

Lydi Conklin was one of 10 nonbinary authors I read from this year. Had I read their novel earlier, this would have made it into my Cover Love post!

Nonbinary author: 3.2% (↑2.1%)

BIPOC author: 18.5% (↑0.1%)

How to get it to 25% or more??

LGBTQ: 20.4% (↓1.1%)

(Author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) It’s the first time this has decreased since 2021, but I’m still pleased with the figure overall.

Work in translation: 9.6% (↑3.6%)

Going the right way with this trend! 10% seems like a good minimum to aim for. I find I have to make a conscious effort by accepting translated review copies or picking them off my shelves to tie in with particular reading challenges.

German (6) – mainly because of our trip in September

French (5)

Swedish (4)

Korean (3)

Italian (2)

Italian (2)

Japanese (2)

Spanish (2)

Chinese (1)

Dutch (1)

Norwegian (1)

Polish (1)

Portuguese (1)

Russian (1)

2025 (or pre-release 2026) books: 55.6% (↑3.2%)

Backlist: 44.4%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read eight pre-1950 books, the oldest being Diary of a Nobody from 1892.

E-books: 35.5% (↑3.4%)

Print books: 64.5%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews. The number of overall Shelf Awareness reviews will be decreasing because of changes to their publishing model, so this figure may well change by next year.

Rereads: 11, vs. last year’s 18

I managed nearly one a month. Like last year, three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences of the year, so I should really reread more often.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

- 69,616 pages read

- Average book length: 221 pages (just one off of last year’s 220; in previous years it has always been 217–225, driven downward by poetry collections and novellas)

- Average rating for 2025: 6 (identical to the last three years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2024:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 33.9% (↓10.9%)

- Public library: 18.8% (↑0.4%)

- Free (gifts, giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 15.3% (↑2.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss or BookSirens: 15% (↑7.2%)

- Secondhand purchase: 12.8% (↑1.3%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.6% (↓0.5%)

- University library: 1.3% (↓0.7%)

- Other (church theological library): 0.3% (↑0.3%)

I’m pleased that 30.3% of my reading was from my own shelves, versus last year’s 24%. It looks like I mainly achieved this through a reduction in review copies. In 2026, I’d like to read even more backlist material from my own shelves (including rereads). This will be a particular focus in January, and then I’ll plan how to incorporate it for the rest of the year.

I have an absurd number of review books to catch up on (42), some stretching back to 2022 – the year of my mother’s death, which put me off my stride in many ways – as well as part-read books (116) to get real about and either finish or call DNFs and clear from my shelves. Dealing with these can be part of the reading-from-my-shelves initiative.

What trends did you see in your year’s reading? What is your plan for 2026?

Final Reading Statistics for 2024

Happy New Year! Even though we were out at neighbours’ until 2:45 a.m. (who are these party animals?!), I’m feeling bright-eyed and bushy-tailed today and looking forward to a special brunch at our favourite Newbury establishment. Despite all evidence to the contrary in the news – politically, environmentally, internationally – I’m choosing to be optimistic about what 2025 will hold. What hope I have comes from community and grassroots efforts.

In other good news, 2024 saw my highest reading total yet! (My usual average, as in 2019–21 and 2023, is 340.) Last year I challenged myself to read 350 books and I managed it easily, even though at one point in the middle of the year I was far behind and it didn’t look possible.

Reading a novella a day in November was certainly a major factor in meeting my goal. I also tend to prioritize poetry collections and novellas for my Shelf Awareness reviewing, and in general I consider it a bonus if a book is closer to 200 pages than 300+.

The statistics

Fiction: 51.4%

Nonfiction: 31.8% (similar to last year’s 31.2%)

Poetry: 16.8% (identical to last year!)

Female author: 67.9% (close to last year’s 69.7%)

Male author: 29.6%

Nonbinary author: 1.1%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 1.4%

BIPOC author: 18.4%

This has dropped a bit compared to previous years’ 22.4% (2023), 20.7% (2022), and 18.5% (2021). My aim will be to make it 25% or more.

LGBTQ: 21.6%

(Based on the author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) This has been increasing from 11.8% (2021), 8.8% (2022), and 18.2% (2023). I’m pleased!

Work in translation: 6%

I read only 21 books in translation last year, alas. This is an unfortunate drop from the previous year’s 10.6%. I do prefer to be closer to 10%, so I will need to make a conscious effort to borrow translated books and incorporate them in my challenges.

French (7)

German (4)

Norwegian (3)

Spanish (3)

Italian (1)

Latvian (1) – a new language for me to have read from

Swedish (1)

+ Misc. in a story anthology

2024 (or pre-release 2025) books: 52.3% (up from 44.7% last year)

Backlist: 47.7%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read five pre-1950 books, the oldest being Howards End and Kilmeny of the Orchard, both from 1910. I should definitely pick up something from the 19th century or earlier next year!

E-books: 32.1% (up from 27.4% last year)

Print books: 67.9%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews.

Rereads: 18

I doubled last year’s 9! I’m really happy with this 1.5/month average. Three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences for the year.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

Average book length: 220 pages (in previous years it has been 217 and 225)

Average rating for 2024: 3.6 (identical to the last two years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2023:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 44.8% (↑1.3%)

- Public library: 18.4% (↓5.7%)

- Secondhand purchase: 11.5% (↑1.7%)

- Free (giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 9.8% (↑3.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss, BookSirens or Project Gutenberg: 8.8% (↑2%)

- Gifts: 2.6% (↓1.5%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.1% (↓2.6%)

- University library: 2% (↓1.2%)

So, like last year, nearly a quarter of my reading (24%) was from my own shelves. I’d like to make that more like a third to half, which would be better achieved by a reduction in the number of review copies rather than a drop in my library borrowing. It would also ensure that I read more backlist books.

What trends and changes did you see in your year’s reading?

Three on a Theme: Trans Poetry for National Poetry Day

Today is National Poetry Day here in the UK. Alfie and I spent part of the chilly early morning reading from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s super Poetry Unbound, an anthology of 50 poems to which he’s devoted personal introductions and exploratory essays. He describes poetry as “like a flame: helping us find our way, keeping us warm.”

Poetry Unbound is also the name of his popular podcast; both were recommended to me by Sara Beth West, my fellow Shelf Awareness reviewer, in this interview we collaborated on back in April (National Poetry Month in the USA) about reading and reviewing poetry. I’ve been a keen reader of contemporary poetry for 15 years or so, but in the 3.5 years that I’ve been writing for Shelf I’ve really ramped up. Most months, I review a couple poetry collections for that site, and another one or more on here.

Two of my Shelf poetry reviews from the past 10 months highlight the trans experience; when I recently happened to read another collection by a trans woman, I decided to gather them together as a trio. All three pair the personal – a wrestling over identity – with the political, voicing protest at mistreatment.

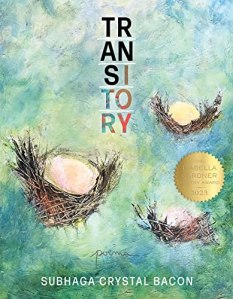

Transitory by Subhaga Crystal Bacon (2023)

In her Isabella Gardner Award-winning fourth collection, queer poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon commemorates the 46 trans and gender-nonconforming people murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020—an “epidemic of violence” that coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The statistics Bacon conveys are heartbreaking: “The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years of age”; “Half of Black trans women spend time in jail”; “Trans people are anywhere/ between eleven and forty percent/ of the homeless population.” She also draws on her own experience of gender nonconformity: “A little butch./ A little femme.” She recalls of visiting drag bars in the 1980s: “We were all/ trying on gender.” And she vows: “No one can say a life is not right./ I have room for you in me.” Her poetic memorial is a valuable exercise in empathy.

Published by BOA Editions. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I was interested to note that the below poets initially published under both female and male, new and dead names, as shown on the book covers. However, a look at social media makes it clear that the trans women are now going exclusively by female names.

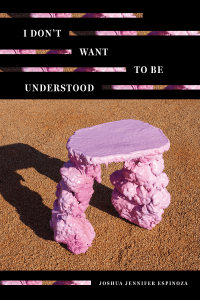

I Don’t Want to Be Understood by Jennifer Espinoza (2024)

In Espinoza’s undaunted fourth poetry collection, transgender identity allows for reinvention but also entails fear of physical and legislative violence.

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Words build into stanzas, prose paragraphs, a zigzag line, or cross-hatching. Espinoza likens the body to a vessel for traumatic memories: “time is a body full of damage// that is constantly trying to forget.” Alliteration and repetition construct litanies of rejection but, ultimately, of hope: “When I call myself a woman I am praying.”

Published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

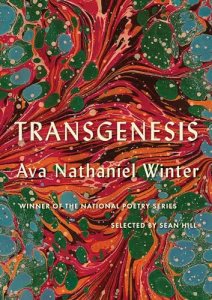

Transgenesis by Ava Winter (2024)

“The body is holy / and is made holy in its changing.”

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Let me greet now,

with warm embrace,

the small blue tablets

I place beneath my tongue each morning.

Oh estradiol,

daily reminder

of what our bodies

have always known:

the many forms of beauty that might be made

flesh by desire, by chance, by animal action.

(from “Transgenesis”)

The first time I wore a dress in public without a hint of irony—a Max Mara wrap adorned with Japanese lilies that framed my shoulders perfectly—I was still thin but also thickly bearded and men on the train whispered to me in a conspiratorial tone, as if they hoped the dress were a joke I might let them in on.

(from “WWII SS Wiking Division Badge, $55”)

– and faith grants affirmation that “there is beauty in such queer and fruitless bodies,” as the title poem insists, with reference to the saris (nonbinary person) acknowledged by the Talmudic rabbis. “Lament with Cello Accompaniment” provides an achingly gorgeous end to the collection:

I do not choose the sound of the song

In my mouth, the fading taste of what I still live through, but I choose this future, as I bury a name defined by grief, as I enter the silence where my voice will take shape.

Winter teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I’ll look out for more of her work.

Published by Milkweed Editions. (Read via Edelweiss)

More trans poetry I have read:

A Kingdom of Love & Eleanor Among the Saints by Rachel Mann

By nonbinary/gender-nonconforming poets, I have also read:

Surge by Jay Bernard

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest

Binded by H Warren

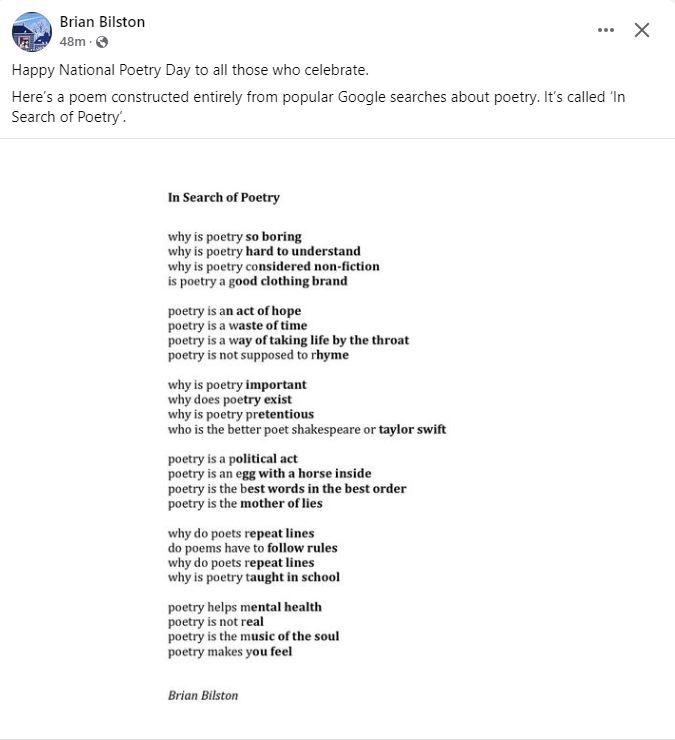

Extra goodies for National Poetry Day:

Follow Brian Bilston to add a bit of joy to your feed.

Editor Rosie Storey Hilton announces a poetry anthology Saraband are going to be releasing later this month, Green Verse: Poems for our Planet. I’ll hope to review it soon.

Two poems that have been taking the top of my head off recently (in Emily Dickinson’s phrasing), from Poetry Unbound (left) and Seamus Heaney’s Field Work:

Summer Reading, Part II: Beanland, Watters; O’Farrell, Oseman Rereads

Apparently the UK summer officially extends to the 22nd – though you’d never believe it from the autumnal cold snap we’re having just now – so that’s my excuse for not posting about the rest of my summery reading until today. I have a tender ancestry-inspired story of a Jewish family’s response to grief, a bizarre YA fantasy comic, and two rereads, one a family story from one of my favourite contemporary authors and the other the middle instalment in a super-cute graphic novel series.

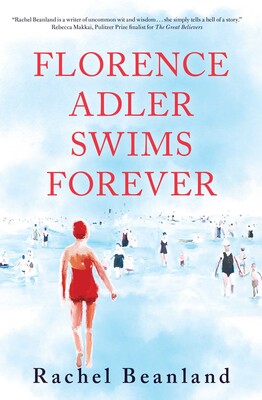

Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland (2020)

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

The particulars can be chalked up to family history: this really happened; the Gussie character was Beanland’s grandmother, and the author believes her great-great-aunt Florence died of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It’s intriguing to get glimpses of Jewish ritual, U.S. anti-Semitism and early concern over Nazism, but I was less engaged with other subplots such as Fannie’s husband Isaac’s land speculation in Florida. There’s a satisfying queer soupcon, and Beanland capably inhabits all of the perspectives and the bereaved mindset. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Lumberjanes: Campfire Songs by Shannon Watters et al. (2020)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library) ![]()

And the rereads:

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell (2013)

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I had forgotten the two major reveals, but this time they didn’t seem as important as the overall sense of decisions with unforeseen consequences. O’Farrell was using extreme weather as a metaphor for risk and cause-and-effect (“a heatwave will act upon people. It lays them bare, it wears down their guard. They start behaving not unusually but unguardedly”), and it mostly works. But this wasn’t a top-tier O’Farrell on a reread. (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Average: ![]()

Heartstopper: Volume 3 by Alice Oseman (2020)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library) ![]()

Any final “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research. The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint.

The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint. Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride.

Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride. As I found when I

As I found when I  I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to  Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis.

Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis. I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

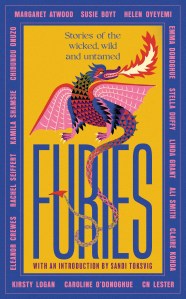

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library) As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,  Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after