Richard Rohr at Greenbelt Festival (Online) & The Naked Now Review

Back in late August, I attended another online talk that really chimed with the one by Richard Holloway, this time as part of Greenbelt Festival, a progressive Christian event we used to attend annually but haven’t been to in many years now.

Not just as a Covid holdover but also in a conscious sustainability effort, Greenbelt hosted a “fly-free zone” where overseas speakers appeared on a large screen instead of travelling thousands of miles. So Richard Rohr, who appeared old and frail to me – no wonder, as he is now 81 and has survived five unrelated cancers (doctors literally want to do a genetic study on him) – appeared from the communal lounge of his Center for Action and Contemplation in New Mexico to introduce his upcoming book The Tears of Things, due in March 2025. The title is from the same Virgil quote as Holloway’s The Heart of Things. It’s about the Old Testament prophets’ shift from rage to lamentation to doxology (“the great nevertheless,” he called it): a psychological journey we all must make as part of becoming spiritually mature.

From reading his Falling Upward, I was familiar with Rohr’s central teaching of life being in two halves: the first, ego-led, is about identity and argumentation; the second is about transcending the self to tap into a universal consciousness. “It’s a terrible burden to carry your own judgementalism,” he declared. A God encounter provokes the transformation, and generally it comes through suffering, he said; you can’t take a shortcut. Anger is a mark of “incomplete” prophets such as John the Baptist, he explained. Rage might seem to empower, but it’s unrefined and only gives people permission to be nasty to others, he said. We can’t preach about a wrathful God or we will just produce wrathful people, he insisted; instead, we have to teach mercy.

When Rohr used to run rites of passage for young men, he would tell them that they weren’t actually angry, they were sad. There are tears that come from God, he said: for Gaza, for Ukraine. We know that Jesus wept at least twice, as recorded in scripture: once for Jerusalem (the collective) and once for his dead friend Lazarus (the individual). Doing the “grief work” is essential, he said. A parallel to that anger to sadness to praise trajectory is order to disorder to reorder, a paradigm he takes from the Bible’s wisdom literature. Brian McLaren’s recent work is heavily influenced by these ideas, too.

During the question time, Rohr was drawn out on the difference between Buddhism and Christianity (the latter gives reality a personal and benevolent face, he said) and how he understands hope – it is participation in the life of God, he said, and it certainly doesn’t come from looking at the data. He lauded Buddhism for its insistence on non-dualism or unitive consciousness, which he also interprets as the “mind of Christ.” The love of God is the Absolute, he said, and although he has experienced it throughout his life, he has known it especially when (as now) he was weak and poor.

Non-dualism is the theme that led me to go back to a book that had been on my bedside table, partly read, for months.

The Naked Now: Learning to See as the Mystics See (2009)

This was my fourth book by Rohr, and as with The Universal Christ, I feel at a loss trying to express how wise and earth-shaking it is. The kernel of the argument is simple. Dualistic thinking is all or nothing, us and them. The mystical view of life involves nonduality; not knowing the right things but “knowing better” through contemplation. It’s an opening of the heart that then allows for a change of mind. And yes, as he said at Greenbelt, it mostly comes about through great suffering – or great love. Jesus embodies nonduality by being not human or divine, but both, as does God through the multiplicity of the Trinity.

This was my fourth book by Rohr, and as with The Universal Christ, I feel at a loss trying to express how wise and earth-shaking it is. The kernel of the argument is simple. Dualistic thinking is all or nothing, us and them. The mystical view of life involves nonduality; not knowing the right things but “knowing better” through contemplation. It’s an opening of the heart that then allows for a change of mind. And yes, as he said at Greenbelt, it mostly comes about through great suffering – or great love. Jesus embodies nonduality by being not human or divine, but both, as does God through the multiplicity of the Trinity.

The book completely upends the fundamentalist Christianity I grew up with. Its every precept is based on Bible quotes or Christian tradition. It’s only 160 pages long, very logical and readable; I only went through it so slowly because I had to mark out and reread brilliant passages every few pages.

You can tell adult and authentic faith by people’s ability to deal with darkness, failure, and nonvalidation of the ego—and by their quiet but confident joy!

[I’ve met people who are like this.]

If your religious practice is nothing more than to remain sincerely open to the ongoing challenges of life and love, you will find God — and also yourself.

[This reminded me of “God is change,” the doctrine in Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler.]

If you can handle/ignore a bit of religion, I would recommend Rohr to readers of Brené Brown, Susan Cain (thinking of Bittersweet in particular) and Anne Lamott, among other self-help and spirituality authors – e.g., he references Eckhart Tolle. Rohr is also known for being one of the popularizers of the Enneagram, a personality tool similar to the Myers-Briggs test but which in its earliest form dates back to the Desert Father Evagrius Ponticus. ![]()

Edinburgh Book Festival 2024 (Online): Richard Holloway’s On Reflection

Thanks to Kate for making me aware that the Edinburgh Book Festival was running in hybrid format this year, allowing people hundreds or thousands of miles away to participate. It felt like a return to the good old days of coronavirus lockdown – yes, I know it was very bad for very many people, but one consolation, especially for a thrifty introvert like me, was the chance to attend a plethora of literary and musical events online without leaving my sofa. I donated to live-stream two talks, one by Olivia Laing last week (more on that in an upcoming post on three recent gardening-themed reads) and this one by Richard Holloway on Sunday.

Alfie was rapt, too, of course.

I’ve reviewed several of his books here before (The Way of the Cross, Waiting for the Last Bus and The Heart of Things) and it would be fair to call him one of my most-admired spiritual gurus. At age ninety, he is not just lucid but quick-witted and naughty (I wasn’t expecting two F-bombs from a former bishop). While I have not read his latest book, On Reflection, it sounds like it’s quite similar to The Heart of Things: composed of memories and philosophical musings, with lashings of 20th-century poetry and Scottish history.

Interviewer Alan Little, a broadcaster who is stepping down as Festival chair after a decade, drew Holloway out on topics including faith, poetry, the Scottish reformation, and mortality. Little joked, “as you get older, you’re supposed to get more set in your ways!” while Holloway appears to become ever more liberal. He referred to himself as a “non-believing Christian” who is still steeped in religious culture and language but has adopted a “serene, gracious agnosticism,” which is “as much as the universe affords us.”

Holloway recently reread his first book and, while he admired that young man’s enthusiasm, he disliked the hectoring tone. The opposite of faith isn’t doubt, he remarked, but certainty. Two things prompted him to leave the ministry: the Church’s hatred of gay people and its subordination of women. His guiding principle is simple (reminiscent of Jan Morris’s): let’s be kind to each other and look after one another while we’re here. More existentially, he frames it as: let’s live as if life has meaning, even though he’s not sure that it does. In fact, he theorizes that religion arose from death, because we are the only species that is aware of our mortality and we can’t bear the thought of nothingness.

Holloway seems to live and breathe poetry. He expressed his love for W. H. Auden, whom he described as almost “priestly” in his brokenness, struggles, mysticism, and doing of good by stealth (he cared for war orphans and left them money at his death). Although I sometimes feel that Holloway is overly reliant on quotation in his recent books, I appreciate his fervour for poetry. His summation of what it does for him rang true for me as well: “poetry feeds me because it notices things in a particular way.” He added, “at its best, religion is a kind of realized poetry,” exclaiming, if only we could value it as such and not turn it into doctrine.

I wasn’t as interested in the discussion of John Knox and Scottish Presbyterianism, but obviously it was appropriate for the Edinburgh setting. Holloway said that it saddens him that Scotland is losing “the kirk” – as a tradition and in the form of buildings, many of which stand derelict. He read a long passage about Knox’s unfortunate hatred of images (his movement removed or concealed all sacred paintings) and how that rejection comes from the desert religions, which associate emptiness with otherness and the Transcendent.

During the Q&A time, one audience member said that he was heading to a Handel performance next, and hoped for a transcendent experience – but, he asked, being agnostic like Holloway, “what will I transcend to?” The two men seemed to agree that the experience itself is enough. Culture as transmitted by learning is the most distinctive thing about humans, Holloway observed, and Little also spoke passionately about the arts’ role in reconciliation. Several times, Holloway expressed his enduring wonder at the fact that there is something instead of nothing. It still staggers him not just that we’re here, but that we are capable of pondering the meaning of our own existence through events such as this one. That humility, even after his many decades as a respected public thinker, was beautiful to see.

Learning How to Be Sad via Books by Susan Cain and Helen Russell

There’s been a lot of sadness in my life over the past few months. If there’s a key lesson I learned from the latest work by these authors, who are among the best self-help writers out there, it’s that denying sadness is the worst thing we could do. Accepting sadness helps us to be compassionate towards others and to acknowledge but ultimately let go of generational pain. There are measures we can take to mitigate sadness – a focus of the second half of Russell’s book – but it can’t be avoided altogether. Alongside the classics of bereavement literature I have been rereading, I found these two books to be valuable companions in grief.

Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole by Susan Cain (2022)

Cain’s Quiet must be one of the best-known nonfiction books of the millennium. It felt like vindication for introverts everywhere. Bittersweet is a little more nebulous in strategy but, boiled down, is a defence of the melancholic personality, one of the types identified by Aristotle (also explored in Richard Holloway’s The Heart of Things). Sadness is not the same as clinical depression, Cain rushes to clarify, though the two might coexist. Melancholy is often associated with creativity and sensitivity, and can lead us into empathy for others. Suffering and death seem like things to flee, but if we sit with them, we will truly be part of the human race and, per the “wounded healer” archetype, may also work toward restoration.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

Through interviews and attendance at conferences and other events, she draws in various side topics, like the longing that prompts mysticism (Kabbalah and Sufism), loving-kindness meditation, an American culture of positivity that demands “effortless perfection,” ways the business world could cultivate empathy, and how knowledge of death makes life precious. (The only chapter I found less than essential was one about transhumance – the hope of escaping death altogether. Mark O’Connell has that topic covered.) Cain weaves together her research with autobiographical material naturally. As a shy introvert with melancholy tendencies, I found both Quiet and Bittersweet comforting.

With thanks to Viking (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

How to Be Sad: The Key to a Happier Life by Helen Russell (2021)

A reread, though I only skimmed the first time around – my tiny points of criticism would be that the book is a tad long – the print in the paperback is really rather small – and retreads some of the same ground as Leap Year (e.g., how exercise and culture can contribute to a sense of wellbeing). I read that just last year, after enjoying The Year of Living Danishly with my book club. She’s a reliable nonfiction author; I’d liken her to a funnier Gretchen Rubin.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

As in her other self-help work, she interviews lots of experts and people who have gone through similar things to understand why we’re sad and what to do about it. I particularly appreciated chapters on “arrival fallacy” and “summit syndrome,” both of which refer to a feeling of letdown after we achieve what we think will make us happy, whether that be parenthood or the South Pole. Better to have intrinsic goals than external ones, Russell learns.

She also considers cultural differences in how we approach sadness: for instance, Russians relish sadness and teach their children to do the same, whereas the English, especially men, are expected to bury their feelings. Russell notes a waning of the rituals that could help us cope with loss, and a rise in unhealthy coping mechanisms. Like Cain, she also covers sad music (vs. one of her interviewees prescribing Jack Johnson as a mood equalizer). There are lots of laughs to be had, but the epilogue can’t fail to bring a tear to the eye. (Public library)

Both:

I found this quote from the Russell a handy summary of both authors’ premise. Dr Lucy Johnstone says:

“The key question when encountering someone with mental or emotional distress shouldn’t be, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ but rather, ‘What’s happened to you?’”

Suffering is coming for all of us, so why not arm yourself to deal with it and help others through? That’s always been one of my motivations for reading widely: to understand other people’s situations and prepare myself for what the future holds.

Could you see yourself reading a book about sadness?

Book Serendipity, Mid-October to Mid-December 2022

The last entry in this series for the year. Those of you who join me for Love Your Library, note that I’ll host it on the 19th this month to avoid the holidays. Other than that, I don’t know how many more posts I’ll fit in before my year-end coverage (about six posts of best-of lists and statistics). Maybe I’ll manage a few more backlog reviews and a thematic roundup.

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Tom Swifties (a punning joke involving the way a quotation is attributed) in Savage Tales by Tara Bergin (“We get a lot of writers in here, said the rollercoaster operator lowering the bar”) and one of the stories in Birds of America by Lorrie Moore (“Would you like a soda? he asked spritely”).

- Prince’s androgynous symbol was on the cover of Dickens and Prince by Nick Hornby and is mentioned in the opening pages of Shameless by Nadia Bolz-Weber.

- Clarence Thomas is mentioned in one story of Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Encore by May Sarton. (A function of them both dating to the early 1990s!)

- A kerfuffle over a ring belonging to the dead in one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- Excellent historical fiction with a 2023 release date in which the amputation of a woman’s leg is a threat or a reality: one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland.

- More of a real-life coincidence, this one: I was looking into Paradise, Piece by Piece by Molly Peacock, a memoir I already had on my TBR, because of an Instagram post I’d read about books that were influential on a childfree woman. Then, later the same day, my inbox showed that Molly Peacock herself had contacted me through my blog’s contact form, offering a review copy of her latest book!

- Reading nonfiction books titled The Heart of Things (by Richard Holloway) and The Small Heart of Things (by Julian Hoffman) at the same time.

- A woman investigates her husband’s past breakdown for clues to his current mental health in The Fear Index by Robert Harris and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” is a repeated phrase in Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson, as it was in Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin.

- Massive, much-anticipated novel by respected author who doesn’t publish very often, and that changed names along the way: John Irving’s The Last Chairlift (2022) was originally “Darkness as a Bride” (a better title!); Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (2023) started off as “The Maramon Convention.” I plan to read the Verghese but have decided against the Irving.

- Looting and white flight in New York City in Feral City by Jeremiah Moss and Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson.

- Two bereavement memoirs about a loved one’s death from pancreatic cancer: Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik and Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner.

- The Owl and the Pussycat of Edward Lear’s poem turn up in an update poem by Margaret Atwood in her collection The Door and in Anna James’s fifth Pages & Co. book, The Treehouse Library.

- Two books in which the author draws security attention for close observation of living things on the ground: Where the Wildflowers Grow by Leif Bersweden and The Lichen Museum by A. Laurie Palmer.

- Seal and human motherhood are compared in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer, two 2023 memoirs I’m enjoying a lot.

- Mystical lights appear in Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (the Northern Lights, there) and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer.

- St Vitus Dance is mentioned in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and Robin by Helen F. Wilson.

- The history of white supremacy as a deliberate project in Oregon was a major element in Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk, which I read earlier in the year, and has now recurred in The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

The Heart of Things by Richard Holloway (#NovNov22 Nonfiction Week)

This was my sixth book by Holloway, a retired Bishop of Edinburgh whose perspective is maybe not what you would expect from a churchman – he focuses on this life and on practical and emotional needs rather than on the supernatural or abstruse points of theology. His recent work, such as Waiting for the Last Bus, also embraces melancholy in a way that many on the more evangelical end of Christianity might deem shamefully negative.

Being a pessimist myself, though, I find that his outlook resonates. The title of this 2021 release, originally subtitled “An Anthology of Memory and Regret,” comes from Virgil’s Aeneid (“there are tears at the heart of things [sunt lacrimae rerum]”), and that context makes it clearer where he’s coming from. In the same paragraph in which he reveals that source, he defines melancholia as “sorrowing empathy for the constant defeats of the human condition.”

Being a pessimist myself, though, I find that his outlook resonates. The title of this 2021 release, originally subtitled “An Anthology of Memory and Regret,” comes from Virgil’s Aeneid (“there are tears at the heart of things [sunt lacrimae rerum]”), and that context makes it clearer where he’s coming from. In the same paragraph in which he reveals that source, he defines melancholia as “sorrowing empathy for the constant defeats of the human condition.”

The book is in six thematic essays that plait Holloway’s own thoughts with lengthy quotations, especially from 19th- and 20th-century poetry: Passing – Mourning – Warring – Ruining – Regretting – Forgiving. The war chapter, though appropriate for it having just been Remembrance Day, engaged me the least, while the section on ruin sticks closely to the author’s Glasgow childhood and so seems to offer less universal value than the rest. I most appreciated the first two chapters and the one on regret, which features musings on Nietzsche’s “amor fati” and extended quotes from Borges, Housman and MacNeice.

We melancholics are prone to looking backwards, even when we know it’s not good for us; to dwelling on our losses and failures. The final chapter, then, is key, insisting on self-forgiveness because of the forgiveness modelled by Christ (in whatever way you understand that). Holloway believes in the edifying wisdom of poetry, which he calls “greater than the intention of its makers and [continuing] to reveal new meanings long after they are gone.” He’s created an unusual and pensive collection that will perform the same role.

[147 pages]

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Easter Reading from Richard Holloway and Richard Yates

I found a lesser-known Yates novel on my last trip to our local charity warehouse and saved it up for the titular holiday. I also remembered about a half-read theology book I’d packed away with the decorative wooden Easter egg and tin with a rabbit on in the holiday stash behind the spare room bed. And speaking of rabbits…

(I also gave suggestions of potential Easter reading, theological or not, in 2015, 2017, and 2018.)

(I also gave suggestions of potential Easter reading, theological or not, in 2015, 2017, and 2018.)

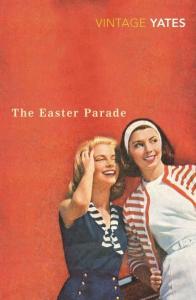

The Easter Parade by Richard Yates (1976)

Yates sets out his stall with the first line: “Neither of the Grimes sisters would have a happy life, and looking back, it always seemed that the trouble began with their parents’ divorce.” I’d seen the film of Revolutionary Road, and my impression of Yates’s work was confirmed by this first taste of his fiction: an atmosphere of mid-century (sub)urban ennui, with the twin ills of alcoholism and adultery causing the characters to drift inexorably towards tragedy.

The novel follows Sarah and Emily Grimes from the 1930s to the 1970s. Emily, four years younger, has always known that her sister is the pretty one. Twenty-year-old Sarah is tapped to model traditional Chinese dress during an Easter parade and be photographed by the public relations office of United China Relief, for whom she works in fundraising. Sarah had plans with her fiancé, Tony Wilson, and is unenthusiastic about taking part in the photo shoot, while Emily thinks what she wouldn’t give to appear in the New York Times.

The mild rivalry resurfaces in the years to come, though the sisters take different paths: Sarah marries Tony, has three sons, and moves to the Wilson family home out on Long Island; in New York City, Emily keeps up an unending stream of lovers and English-major jobs: bookstore clerk, librarian, journal editor, and ad agency copywriter. Sarah envies Emily’s ability to live as a free spirit, while Emily wishes she could have Sarah’s loving family home – until she learns that it’s not as idyllic as it appears.

The mild rivalry resurfaces in the years to come, though the sisters take different paths: Sarah marries Tony, has three sons, and moves to the Wilson family home out on Long Island; in New York City, Emily keeps up an unending stream of lovers and English-major jobs: bookstore clerk, librarian, journal editor, and ad agency copywriter. Sarah envies Emily’s ability to live as a free spirit, while Emily wishes she could have Sarah’s loving family home – until she learns that it’s not as idyllic as it appears.

What I found most tragic wasn’t the whiskey-soused poor decisions so much as the fact that both sisters have unrealized ambitions as writers. They long to follow in their headline-writing father’s footsteps: Emily starts composing a personal exposé on abortion, and later a witty travel guide to the Midwest when she accompanies a poet boyfriend to Iowa so he can teach in the Writers’ Workshop; Sarah makes a capable start on a book about the Wilson family history. But both allow their projects to wither, and their promise is unfulfilled.

Yates’s authentic characterization, forthright prose, and incisive observations on the futility of modern life and the ways we choose to numb ourselves kept this from getting too depressing – though I don’t mind bleak books. Much of the novel sticks close to Emily, who can, infuriatingly, be her own worst enemy. Yet the ending offers her the hand of grace in the form of her nephew Peter, a minister. I read the beautiful final paragraphs again and again.

A readalike I’ve reviewed (sisters, one named Sarah!): A Summer Bird-Cage by Margaret Drabble

My rating: ![]()

The Way of the Cross by Richard Holloway (1986)

Each year the Archbishop of Canterbury commissions a short book for the Anglican Communion to use as Lenten reading. This study of the crucifixion focuses on seven of the Stations of the Cross, which are depicted in paintings or sculptures in most Anglo-Catholic churches, and emphasizes Jesus’s humble submission and the irony that the expected Son of God came as an executed criminal rather than an exalted king. Holloway weaves scripture passages and literary quotations through each chapter, and via discussion questions encourages readers to apply the themes of power, envy, sin, and the treatment of women to everyday life – not always entirely naturally, and the book does feel dated. Not a stand-out from a prolific author I’ve enjoyed in the past (e.g., Waiting for the Last Bus).

Each year the Archbishop of Canterbury commissions a short book for the Anglican Communion to use as Lenten reading. This study of the crucifixion focuses on seven of the Stations of the Cross, which are depicted in paintings or sculptures in most Anglo-Catholic churches, and emphasizes Jesus’s humble submission and the irony that the expected Son of God came as an executed criminal rather than an exalted king. Holloway weaves scripture passages and literary quotations through each chapter, and via discussion questions encourages readers to apply the themes of power, envy, sin, and the treatment of women to everyday life – not always entirely naturally, and the book does feel dated. Not a stand-out from a prolific author I’ve enjoyed in the past (e.g., Waiting for the Last Bus).

Favorite lines:

“the yearly remembrance of the life of Christ is a way of actualizing and making that life present now, in the universal mode of sacramental reality.”

“Powerlessness is the message of the cross”

My rating: ![]()

Recently read for book club; I’ll throw it in here for its dubious thematic significance (the protagonist starts off as an innocently blasphemous child and, disappointed with God as she’s encountered him thus far, gives that name to her pet rabbit):

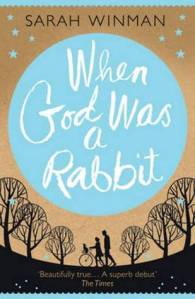

When God Was a Rabbit by Sarah Winman (2011)

I’d enjoyed Winman’s 2017 Tin Man so was very disappointed with this one. You can tell it was a debut novel because she really threw the kitchen sink in when it comes to quirkiness and magic realism. Secondary characters manage to be more engaging than the primary ones though they are little more than a thumbnail description: the lesbian actress aunt, the camp old lodger, etc. I also hate the use of 9/11 as a plot device, something I have encountered several times in the last couple of years, and stupid names like Jenny Penny. Really, the second part of this novel just feels like a rehearsal for Tin Man in that it sets up a close relationship between two gay men and a woman.

I’d enjoyed Winman’s 2017 Tin Man so was very disappointed with this one. You can tell it was a debut novel because she really threw the kitchen sink in when it comes to quirkiness and magic realism. Secondary characters manage to be more engaging than the primary ones though they are little more than a thumbnail description: the lesbian actress aunt, the camp old lodger, etc. I also hate the use of 9/11 as a plot device, something I have encountered several times in the last couple of years, and stupid names like Jenny Penny. Really, the second part of this novel just feels like a rehearsal for Tin Man in that it sets up a close relationship between two gay men and a woman.

Two major themes, generally speaking, are intuition and trauma: characters predict things that they couldn’t know by ordinary means, and have had some awful things happen to them. Some bottle it all up, only for it to explode later in life; others decide not to let childhood trauma define them. This is a worthy topic, certainly, but feels at odds with the carefully cultivated lighthearted tone. Winman repeatedly introduces something sweet or hopeful only to undercut it with a tragic turn of events.

The title phrase comes from a moment of pure nostalgia for childhood, and I think the novel may have been better if it had limited itself to that rather than trying to follow all the characters into later life and sprawling over nearly 40 years. Ultimately, I didn’t feel that I knew much about Elly, the narrator, or what makes her tick, and Joe and Jenny Penny almost detract from each other. Pick one or the other, brother or best friend, to be the protagonist’s mainstay; both was unnecessary.

My rating: ![]()

Book Serendipity Incidents of 2019 (So Far)

I’ve continued to post my occasional reading coincidences on Twitter and/or Instagram. This is when two or more books that I’m reading at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once – usually between 10 and 20 – I guess I’m more prone to such serendipitous incidents. (The following are in rough chronological order.)

What’s the weirdest coincidence you’ve had lately?

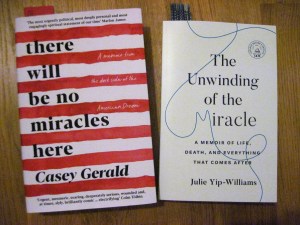

- Two titles that sound dubious about miracles: There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and The Unwinding of the Miracle: A Memoir of Life, Death, and Everything that Comes After by Julie Yip-Williams

- Two titles featuring light: A Light Song of Light by Kei Miller and The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer

- Grey Poupon mustard (and its snooty associations, as captured in the TV commercials) mentioned in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody” (the Whitney Houston song) referenced in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody” (the Whitney Houston song) referenced in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

- Two books have an on/off boyfriend named Julian: Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp and Extinctions by Josephine Wilson

- There’s an Aunt Marjorie in When I Had a Little Sister by Catherine Simpson and Extinctions by Josephine Wilson

- Set (at least partially) in a Swiss chalet: This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer

- A character named Kiki in The Sacred and Profane Love Machine by Iris Murdoch, The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer, AND Improvement by Joan Silber

Two books set (at least partially) in mental hospitals: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning and Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

Two books set (at least partially) in mental hospitals: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning and Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

- Two books in which a character thinks the saying is “It’s a doggy dog world” (rather than “dog-eat-dog”): The Friend by Sigrid Nunez and The Octopus Museum by Brenda Shaughnessy

- Reading a novel about Lee Miller (The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer), I find a metaphor involving her in My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh: (the narrator describes her mother) “I think she got away with so much because she was beautiful. She looked like Lee Miller if Lee Miller had been a bedroom drunk.” THEN I come across a poem in Clive James’s Injury Time entitled “Lee Miller in Hitler’s Bathtub”

- On the same night that I started Siri Hustvedt’s new novel, Memories of the Future, I also started a novel that had a Siri Hustvedt quote (from The Blindfold) as the epigraph: Besotted by Melissa Duclos

- In two books “elicit” was printed where the author meant “illicit” – I’m not going to name and shame, but one of these instances was in a finished copy! (the other in a proof, which is understandable)

- Three books in which the bibliography is in alphabetical order BY BOOK TITLE! Tell me this is not a thing; it will not do! (Vagina: A Re-education by Lynn Enright; Let’s Talk about Death (over Dinner) by Michael Hebb; Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie)

References to Gerard Manley Hopkins in Another King, Another Country by Richard Holloway, This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt (these last two also discuss his concept of the “inscape”)

References to Gerard Manley Hopkins in Another King, Another Country by Richard Holloway, This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt (these last two also discuss his concept of the “inscape”)

- Creative placement of words on the page (different fonts; different type sizes, capitals, bold, etc.; looping around the page or at least not in traditional paragraphs) in When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt [not pictured below], How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain de Botton, Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Alice Iris Red Horse: Selected Poems of Yoshimasu Gozo and Lanny by Max Porter

- Twin brothers fall out over a girl in Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese and one story from the upcoming book Meteorites by Julie Paul

- Characters are described as being “away with the fairies” in Lanny by Max Porter and Away by Jane Urquhart

Schindler’s Ark/List is mentioned in In the Beginning: A New Reading of the Book of Genesis by Karen Armstrong and Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie … makes me think that I should finally pick up my copy!

Schindler’s Ark/List is mentioned in In the Beginning: A New Reading of the Book of Genesis by Karen Armstrong and Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie … makes me think that I should finally pick up my copy!

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

Gordon and Jean Hay stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home starting in 2009. Elizabeth Hay is one of four children, but caregiving fell to her for one reason and another, and it was a fraught task because of her parents’ prickly personalities: Jean was critical and thrifty to the point of absurdity, spooning thick mold off apple sauce before serving it and needling Elizabeth for dumping perfectly good chicken juice a year before; Gordon had a terrible temper and a history of corporal punishment of his children and of his students when he was a school principal. Jean’s knee surgery and subsequent infection finally put paid to their independence; her mind was never the same and she could no longer paint.

Gordon and Jean Hay stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home starting in 2009. Elizabeth Hay is one of four children, but caregiving fell to her for one reason and another, and it was a fraught task because of her parents’ prickly personalities: Jean was critical and thrifty to the point of absurdity, spooning thick mold off apple sauce before serving it and needling Elizabeth for dumping perfectly good chicken juice a year before; Gordon had a terrible temper and a history of corporal punishment of his children and of his students when he was a school principal. Jean’s knee surgery and subsequent infection finally put paid to their independence; her mind was never the same and she could no longer paint. Culture Declares Emergency launched in April to bring the arts into the conversation about the climate emergency. Letters to the Earth compiles 100 short pieces by known and unknown names alike. Alongside published authors, songwriters, professors and politicians are lots of ordinary folk, including children as young as seven. The brief was broad: to write a letter in response to environmental crisis, whether to or from the Earth, to future generations (there are wrenching pieces written to children: “What can I say, now that it’s too late? … that I’m sorry, that I tried,” writes Stuart Capstick), to the government or to other species.

Culture Declares Emergency launched in April to bring the arts into the conversation about the climate emergency. Letters to the Earth compiles 100 short pieces by known and unknown names alike. Alongside published authors, songwriters, professors and politicians are lots of ordinary folk, including children as young as seven. The brief was broad: to write a letter in response to environmental crisis, whether to or from the Earth, to future generations (there are wrenching pieces written to children: “What can I say, now that it’s too late? … that I’m sorry, that I tried,” writes Stuart Capstick), to the government or to other species. I loved

I loved  [Trans. from the Norwegian by Barbara J. Haveland]

[Trans. from the Norwegian by Barbara J. Haveland] The answer to that rhetorical question is nothing much, at least not inherently, so this ends up becoming a book of two parts, with the bereavement strand (printed in green and in a different font – green is for grief? I suppose) engaging me much more than the mushroom-hunting one, which takes her to Central Park and the annual Telluride, Colorado mushroom festival as well as to Norway’s woods again and again – “In Norway, outdoor life is tantamount to a religion.” But the quest for wonder and for meaning is a universal one. In addition, if you’re a mushroom fan you’ll find gathering advice, tasting notes, and even recipes. I fancy trying the “mushroom bacon” made out of oven-dried shiitakes.

The answer to that rhetorical question is nothing much, at least not inherently, so this ends up becoming a book of two parts, with the bereavement strand (printed in green and in a different font – green is for grief? I suppose) engaging me much more than the mushroom-hunting one, which takes her to Central Park and the annual Telluride, Colorado mushroom festival as well as to Norway’s woods again and again – “In Norway, outdoor life is tantamount to a religion.” But the quest for wonder and for meaning is a universal one. In addition, if you’re a mushroom fan you’ll find gathering advice, tasting notes, and even recipes. I fancy trying the “mushroom bacon” made out of oven-dried shiitakes. McLaren was commissioned to launch a series that was part travel guide, part spiritual memoir and part theological reflection. Specifically, he was asked to write about the Galápagos Islands because he’d been before and they were important to him. He joins a six-day eco-cruise that tours around the island chain off Ecuador, with little to do except observe the birds, tortoises and iguanas, and swim with fish and sea turtles. For him this is a peaceful, even sacred place that reminds him of the beauty that still exists in the world despite so much human desecration. Although he avoids using his phone except to quickly check in with his wife, modernity encroaches unhelpfully through a potential disaster with his laptop.

McLaren was commissioned to launch a series that was part travel guide, part spiritual memoir and part theological reflection. Specifically, he was asked to write about the Galápagos Islands because he’d been before and they were important to him. He joins a six-day eco-cruise that tours around the island chain off Ecuador, with little to do except observe the birds, tortoises and iguanas, and swim with fish and sea turtles. For him this is a peaceful, even sacred place that reminds him of the beauty that still exists in the world despite so much human desecration. Although he avoids using his phone except to quickly check in with his wife, modernity encroaches unhelpfully through a potential disaster with his laptop. From one end of the spectrum (progressive Christianity) to the other (atheism). Here’s a different perspective from a sociology professor at California’s Pitzer College. Zuckerman’s central argument is that humanism and free choice can fuel ethical behavior; since there’s no proof of God’s existence and theists have such a wide range of beliefs, it’s absurd to slap a “because God says so” label on our subjective judgments. Morals maintain the small communities our primate ancestors evolved into, with specific views (such as on homosexuality) a result of our socialization. Alas, the in-group/out-group thinking from our evolutionary heritage is what can lead to genocide. Instead of thinking in terms of ‘evil’, though, Zuckerman prefers Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen’s term, “empathy erosion.”

From one end of the spectrum (progressive Christianity) to the other (atheism). Here’s a different perspective from a sociology professor at California’s Pitzer College. Zuckerman’s central argument is that humanism and free choice can fuel ethical behavior; since there’s no proof of God’s existence and theists have such a wide range of beliefs, it’s absurd to slap a “because God says so” label on our subjective judgments. Morals maintain the small communities our primate ancestors evolved into, with specific views (such as on homosexuality) a result of our socialization. Alas, the in-group/out-group thinking from our evolutionary heritage is what can lead to genocide. Instead of thinking in terms of ‘evil’, though, Zuckerman prefers Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen’s term, “empathy erosion.”