20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

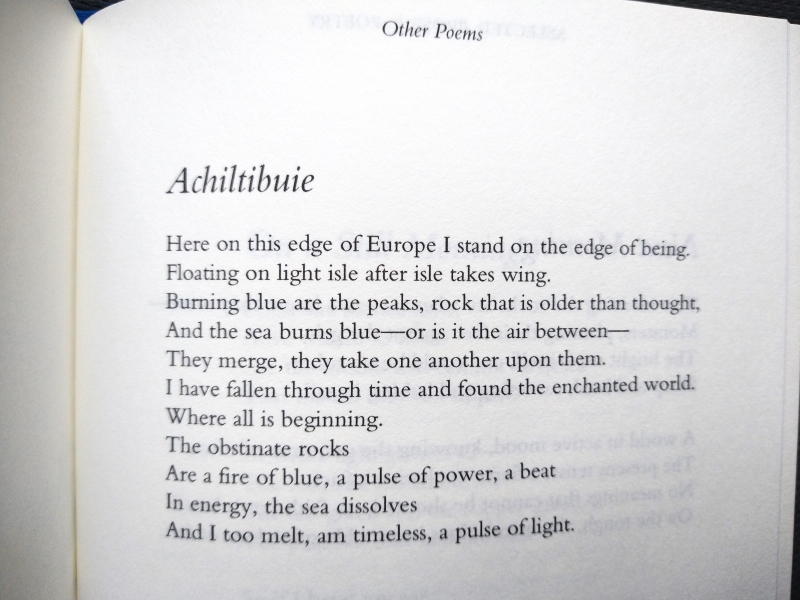

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Edinburgh Book Festival 2024 (Online): Richard Holloway’s On Reflection

Thanks to Kate for making me aware that the Edinburgh Book Festival was running in hybrid format this year, allowing people hundreds or thousands of miles away to participate. It felt like a return to the good old days of coronavirus lockdown – yes, I know it was very bad for very many people, but one consolation, especially for a thrifty introvert like me, was the chance to attend a plethora of literary and musical events online without leaving my sofa. I donated to live-stream two talks, one by Olivia Laing last week (more on that in an upcoming post on three recent gardening-themed reads) and this one by Richard Holloway on Sunday.

Alfie was rapt, too, of course.

I’ve reviewed several of his books here before (The Way of the Cross, Waiting for the Last Bus and The Heart of Things) and it would be fair to call him one of my most-admired spiritual gurus. At age ninety, he is not just lucid but quick-witted and naughty (I wasn’t expecting two F-bombs from a former bishop). While I have not read his latest book, On Reflection, it sounds like it’s quite similar to The Heart of Things: composed of memories and philosophical musings, with lashings of 20th-century poetry and Scottish history.

Interviewer Alan Little, a broadcaster who is stepping down as Festival chair after a decade, drew Holloway out on topics including faith, poetry, the Scottish reformation, and mortality. Little joked, “as you get older, you’re supposed to get more set in your ways!” while Holloway appears to become ever more liberal. He referred to himself as a “non-believing Christian” who is still steeped in religious culture and language but has adopted a “serene, gracious agnosticism,” which is “as much as the universe affords us.”

Holloway recently reread his first book and, while he admired that young man’s enthusiasm, he disliked the hectoring tone. The opposite of faith isn’t doubt, he remarked, but certainty. Two things prompted him to leave the ministry: the Church’s hatred of gay people and its subordination of women. His guiding principle is simple (reminiscent of Jan Morris’s): let’s be kind to each other and look after one another while we’re here. More existentially, he frames it as: let’s live as if life has meaning, even though he’s not sure that it does. In fact, he theorizes that religion arose from death, because we are the only species that is aware of our mortality and we can’t bear the thought of nothingness.

Holloway seems to live and breathe poetry. He expressed his love for W. H. Auden, whom he described as almost “priestly” in his brokenness, struggles, mysticism, and doing of good by stealth (he cared for war orphans and left them money at his death). Although I sometimes feel that Holloway is overly reliant on quotation in his recent books, I appreciate his fervour for poetry. His summation of what it does for him rang true for me as well: “poetry feeds me because it notices things in a particular way.” He added, “at its best, religion is a kind of realized poetry,” exclaiming, if only we could value it as such and not turn it into doctrine.

I wasn’t as interested in the discussion of John Knox and Scottish Presbyterianism, but obviously it was appropriate for the Edinburgh setting. Holloway said that it saddens him that Scotland is losing “the kirk” – as a tradition and in the form of buildings, many of which stand derelict. He read a long passage about Knox’s unfortunate hatred of images (his movement removed or concealed all sacred paintings) and how that rejection comes from the desert religions, which associate emptiness with otherness and the Transcendent.

During the Q&A time, one audience member said that he was heading to a Handel performance next, and hoped for a transcendent experience – but, he asked, being agnostic like Holloway, “what will I transcend to?” The two men seemed to agree that the experience itself is enough. Culture as transmitted by learning is the most distinctive thing about humans, Holloway observed, and Little also spoke passionately about the arts’ role in reconciliation. Several times, Holloway expressed his enduring wonder at the fact that there is something instead of nothing. It still staggers him not just that we’re here, but that we are capable of pondering the meaning of our own existence through events such as this one. That humility, even after his many decades as a respected public thinker, was beautiful to see.

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

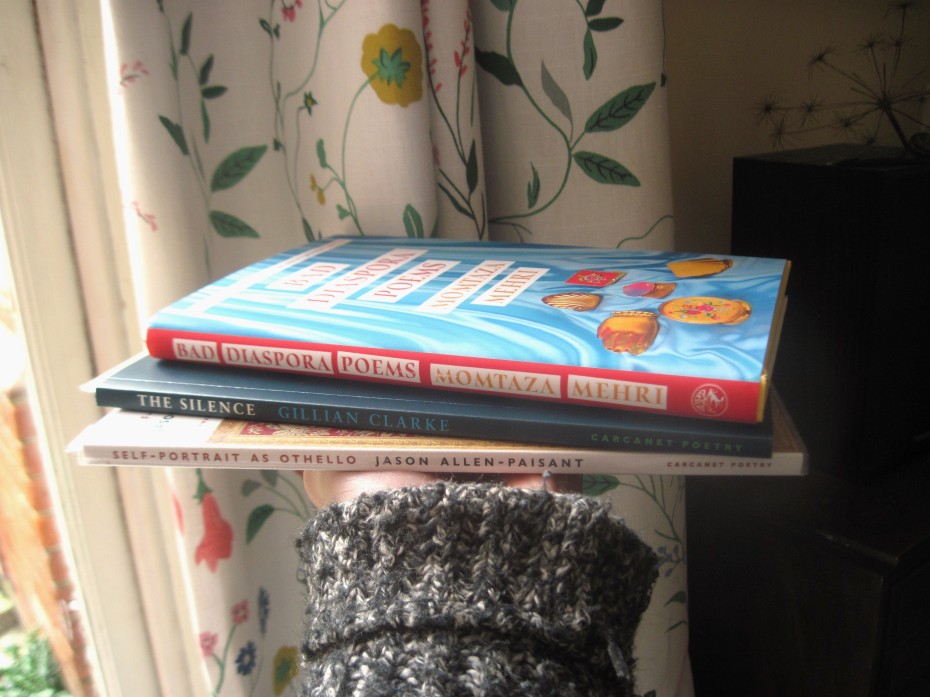

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

August Releases: Bright Fear, Uprooting, The Farmer’s Wife, Windswept

This month I have three memoirs by women, all based on a connection to land – whether gardening, farming or crofting – and a sophomore poetry collection that engages with themes of pandemic anxiety as well as crossing cultural and gender boundaries.

My August highlight:

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan

Chan’s Flèche was my favourite poetry collection of 2019. Their follow-up returns to many of the same foundational subjects: race, family, language and sexuality. But this time, the pandemic is a lens through which all is filtered. This is particularly evident in Part I, “Grief Lessons.” “London, 2020” and “Hong Kong, 2003,” on facing pages, contrast Covid-19 with SARS, the major threat when they were a teenager. People have always made assumptions about them based on their appearance or speech. At a time when Asian heritage merited extra suspicion, English was both a means of frank expression and a source of ambivalence:

“At times, English feels like the best kind of evening light. On other days, English becomes something harder, like a white shield.” (from “In the Beginning Was the Word”)

“my Chinese / face struck like the glow of a torch on a white question: / why is your English so good, the compliment uncertain / of itself.” (from “Sestina”)

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

The poems’ structure varies, with paragraphs and stanzas of different lengths and placement on the page (including, in one instance, a goblet shape). The enjambment, as you can see in lines I’ve quoted above and below, is noteworthy. Part III, “Field Notes on a Family,” reflects on the pressures of being an only child whose mother would prefer to pretend lives alone rather than with a female partner. The book ends with hope that Chan might be able to be open about their identity. The title references the paradoxical nature of the sublime, beautifully captured via the alliteration that closes “Circles”: “a commotion of coots convincing / me to withstand the quotidian tug-/of-war between terror and love.”

Although Flèche still has the edge for me, this is another excellent work I would recommend even to those wary of poetry.

Some more favourite lines, from “Ars Poetica”:

“What my mother taught me was how

to revere the light language emitted.”

“Home, my therapist suggests, is where

you don’t have to explain yourself.”

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Three land-based memoirs:

(All:  )

)

Uprooting: From the Caribbean to the Countryside – Finding Home in an English Country Garden by Marchelle Farrell

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days by Helen Rebanks

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

Growing up, Rebanks started cooking for her family early on, and got a job in a café as a teenager; her mother ran their farm home as a B&B but was forgetful to the point of being neglectful. She met James at 17 and accompanied him to Oxford, where they must have been the only student couple cooking and eating proper food. This period, when she was working an office job, baking cakes for a café, and mourning the devastating foot-and-mouth disease epidemic from a distance, is most memorable. Stories from travels, her wedding, and the births of her four children are pleasant enough, yet there’s nothing to make these experiences, or the telling of them, stand out. I wouldn’t make any of the dishes; most you could find a recipe for anywhere. Eleanor Crow’s black-and-white illustrations are lovely, though.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands by Annie Worsley

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

Would you read one or more of these?

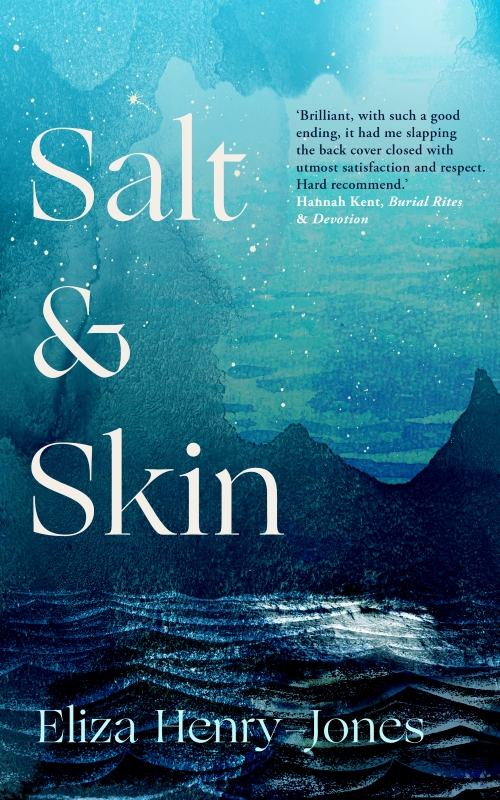

Salt & Skin by Eliza Henry-Jones (Blog Tour)

I was drawn to Eliza Henry-Jones’s fifth novel, Salt & Skin (2022), by the setting: the remote (fictional) island of Seannay in the Orkneys. It tells the dark, intriguing story of an Australian family lured in by magic and motivated by environmentalism. History overshadows the present as they come to realize that witch hunts are not just a thing of the past. This was exactly the right evocative reading for me to take on my trip to some other Scottish islands late last month. The setup reminded me of The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel, while the novel as a whole is reminiscent of The Night Ship by Jess Kidd and Night Waking by Sarah Moss.

Only a week after the Managans – photographer Luda, son Darcy, 16, and daughter Min, 14 – arrive on the island, they witness a hideous accident. A sudden rockfall crushes a little girl, and Luda happens to have captured it all. The photos fulfill her task of documenting how climate change is affecting the islands, but she earns the locals’ opprobrium for allowing them to be published. It’s not the family’s first brush with disaster. The kids’ father died recently; whether in an accident or by suicide is unclear. Nor is it the first time Luda’s camera has gotten her into trouble. Darcy is still angry at her for selling a photograph she took of him in a dry dam years before, even though it raised a lot of money and awareness about drought.

The family live in what has long been known as “the ghost house,” and hints of magic soon seep in. Luda’s archaeologist colleague wants to study the “witch marks” at the house, and Darcy is among the traumatized individuals who can see others’ invisible scars. Their fate becomes tied to that of Theo, a young man who washed up on the shore ten years ago as a web-fingered foundling rumoured to be a selkie. Luda becomes obsessed with studying the history of the island’s witches, who were said to lure in whales. Min collects marine rubbish on her deep dives, learning to hold her breath for improbable periods. And Darcy fixates on Theo, who also attracts the interest of a researcher seeking to write a book about his origins.

It’s striking how Henry-Jones juxtaposes the current and realistic with the timeless and mystical. While the climate crisis is important to the framework, it fades into the background as the novel continues, with the focus shifting to the insularity of communities and outlooks. All of the characters are memorable, including the Managans’ elderly relative, Cassandra (calling to mind a prophetic figure from Greek mythology), though I found Father Lee, the meddlesome priest, aligned too readily with clichés. While the plot starts to become overwrought in later chapters, I appreciated the bold exploration of grief and discrimination, the sensitive attention to issues such as addiction and domestic violence, and the frank depictions of a gay relationship and an ace character. I wouldn’t call this a cheerful read by any means, but its brooding atmosphere will stick with me. I’d be keen to read more from Henry-Jones.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and September Publishing for the free copy for review.

Buy Salt & Skin from the Bookshop UK site. [affiliate link]

or

Pre-order Salt & Skin (U.S. release: September 5) from Bookshop.org. [affiliate link]

I was delighted to help kick off the blog tour for Salt & Skin on its UK publication day. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Scottish Travels & Book Haul: Wigtown, Arran, Islay and Glasgow

When I was a kid, one-week vacations were rare and precious – Orlando or Raleigh for my dad’s church conferences, summer camp in Amish-country Pennsylvania, spring break with my sister in California – and I mourned them when they were over. As an adult, I find that after a week I’m ready to be home … and yet just days after we got back from Scotland, I’m already wondering why I thought everyday life was so great. Oh well. I like to write up my holidays because otherwise it’s all too easy to forget them. This one had fixed start and end points – several days of beetle recording in Galloway for my husband; meeting up with my sister and nephew in Glasgow one evening the next week – and we filled in the intervening time with excursions to two new-to-us Scottish islands; we’re slowly collecting them all.

First Stop, Wigtown

Hard to believe it had been over five years since our first trip to Wigtown. The sleepy little town had barely changed; a couple of bookshops had closed, but there were a few new ones I didn’t remember from last time. The weather was improbably good, sunny and warm enough that I bought a pair of cutoffs at the Community Shop. Each morning my husband set off for bog or beach or wood for his fieldwork and I divided the time until he got back between bits of paid reviewing, reading and book shopping. Our (rather spartan) Airbnb apartment was literally a minute’s walk into town and so was a perfect base.

I paced myself and parcelled out the eight bookshops and several other stores that happen to sell books across the three and a bit days that I had. It felt almost like living there – except I would have to ration my Reading Lasses visits, as a thrice-weekly coffee-and-cake habit would soon get expensive as well as unhealthy. (I spent more on books than on drinks and cakes over the week, though only ~25% more: £44 vs. £32.)

I also had the novelty of seeing my husband interact with his students when we were invited to a barbecue at one’s family home on the Mull of Galloway – and realizing that we’re almost certainly closer in age to the mum than to the student. Getting there required two rural bus journeys to the middle of nowhere, an experience all in itself.

‘Pro’ tips: New Chapter Books was best for bargains, with sections for 50p and £1 paperbacks and free National Geographics. Well-Read Books was good for harder-to-find fiction: among my haul were two Jane Urquhart novels, and the owner was knowledgeable and pleasant. Byre Books carries niche subjects and has scant opening hours, but I procured two poetry collections and a volume of Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals. The Old Bank Bookshop and The Bookshop are the two biggest shops; wander for an hour or more if you can. The Open Book tends to get castoffs from other shops and withdrawn library stock, but I still made two purchases and ended up being the first customer for the week’s hosts: Debbie and Jenny, children’s book authors and long-distance friends from opposite coasts of the USA. Overall, I was pleased with my novella, short story and childhood memoir acquisitions. A better haul than last time.

‘Celebrity’ sightings: On our walk down to the bird hide on the first evening, we passed Jessica Fox, an American expat who’s been influential in setting up the literary festival and The Open Book. She gave us a cheery “hello.” I also spotted Ben of The Bookshop Band twice, once in Reading Lasses and another time on his way to the afternoon school run. Both times he had the baby in tow and I decided not to bother him, not even to introduce myself as one of their Patreon supporters.

On our last morning in town, we lucked out and found Shaun Bythell behind the counter at The Bookshop. He’d just taken delivery of a book-print kilt his staff surprised him by ordering with his credit card, and Nicky (not as eccentric as she’s portrayed in Diary of a Bookseller; she’s downright genteel, in fact) had him model it. He posted a video to Facebook that includes The Open Book hosts on the 23rd, if you wish to see it, and his new cover photo shows him and his staff members wearing the jackets that match the kilt. I bought a few works of paperback fiction and then got him to sign my own copies of two of his books.

As last time, he was chatty and polite, taking an interest in our travels and exhorting us to come back sooner than five years next time. I congratulated him on his success and asked if we could expect more books. He said that depends on his publisher, who worry the market is saturated at the moment, though he has another SIX YEARS of diaries in draft form and the Remainders of the Day epilogue would be quite different if he wrote it now. Tantalizing!

Note to self: Next time, plan to be in town through a Friday evening – we left at noon, so I was sad to miss out on a Beth Porter (the other half of The Bookshop Band) children’s songs concert at Foggie Toddle Books at 3:00, followed by a low-key cocktail party at The Open Book at 5:30 – but not until a Monday, as pretty much everything shuts that day. How I hope someone buys Reading Lasses (the owner is retiring) and maintains the café’s high standard!

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Arran

Our short jaunt to Arran started off poorly with a cancelled ferry sailing, leaving us stranded in Ardrossan (which Bythell had almost prophetically dubbed a “sh*thole” that morning!) for several hours until the next one, and we struggled with a leaky rear tyre and showery weather for much of the time, but we were still enamoured with this island that calls itself “Scotland in miniature.” That was particularly delightful for me because I come from the state nicknamed “America in miniature,” Maryland. This Airbnb was plush by comparison, we obtained excellent food from the Blackwater Bakehouse and a posh French takeaway, and we enjoyed walks at the Machrie stone circles and Brodick Castle as well as at the various bays (one with a fossilized dinosaur footprint) that we stopped off at on our driving tour.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Islay

Islay is a tourist mecca largely because of its nine distilleries – what a pity we don’t care for whiskey! – but we sought it out for its wildlife and scenery, which were reminiscent of what we saw in the Outer Hebrides last year. Our B&B was a bit fusty (there was a rotary phone in the hall!), but we had an unbeatable view from our window and enjoyed visiting two RSPB reserves. The highlight for me was the walk to the Mull of Oa peninsula and the cow-guarded American Monument, which pays tribute to the troops who died in two 1918 naval disasters – a torpedoed boat and a shipwreck – and the heroism of locals who rescued survivors.

We spent a very rainy Tuesday mooching from one distillery shop to another. There are two gin-makers whose products we were eager to taste, but we also relished our mission to buy presents for two landmark birthdays, one of an American friend who’s a whiskey aficionado. Even having to get the tyre replaced didn’t ruin the day. There’s drink aplenty on Islay, but quality food was harder to acquire, so if we went back we’d plump for self-catering.

Incidental additional hauls: I found this 50th anniversary Virago tote bag under a bench at Bowmore harbour after our meal at Peatzeria. I waited a while to see if anyone would come back for it, but it was so sodden and sandy that it must have been there overnight. I cleaned it up and brought home additional purchases in it: two secondhand finds at a thrift store in Tarbert, the first town back on the mainland, and a Knausgaard book I got free with my card points from a Waterstones in Glasgow.

Glasgow

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

With our one day in Glasgow, we decided to prioritize the Burrell Collection, due to the enthusiastic recommendations from Susan, our Arran hosts, and Bill Bryson in Notes on a Small Island (“Among the city’s many treasures, none shines brighter, in my view”). It’s a museum with a difference, housed in a custom-built edifice that showcases the wooded surroundings as much as the stunning objects. We were especially partial to the stained glass.

Our whistle-stop city tour also included a walk past the cathedral, a ramble through the Necropolis (where, pleasingly, I saw a grave for one Elizabeth Pringle), and the Tenement Museum, a very different sort of National Trust house that showed how one woman, a spinster and hoarder, lived in the first half of the 20th century. Then on to an exceptional seafood-heavy meal at Kelp, also recommended by Susan, and an all-too-brief couple of hours with my family at their hotel and a lively pub.

We keep returning to Scotland. Where next in a few years? Possibly the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides, which we didn’t have time for last year, or the more obscure of the Inner Hebrides, before planning return visits to some favourites. All the short ferry rides were smooth this time around, so I can cope with the thought of more.

We got home to find our mullein plants attempting to take over the world.

Love Your Library, June 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation, and to Laura and Naomi for their reviews of books borrowed from libraries. Ever since she was our Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner, I’ve followed Julianne Pachico’s blog. A recent post lists books she currently has from the library. I like her comment that borrowing books “is definitely scratching that dopamine itch for me”! On Instagram I spotted this post celebrating both libraries and Pride Month.

And so to my reading and borrowing since last time.

Most of my reservations seemed to come in all at once, right before we left for Scotland, so I’m taking a giant pile along with me (luckily, we’re traveling by car so I don’t have space or weight restrictions) and will see which I can get to, while also fitting in Scotland-themed reads, June review copies, e-books for paid review, and a few of my 20 Books of Summer!

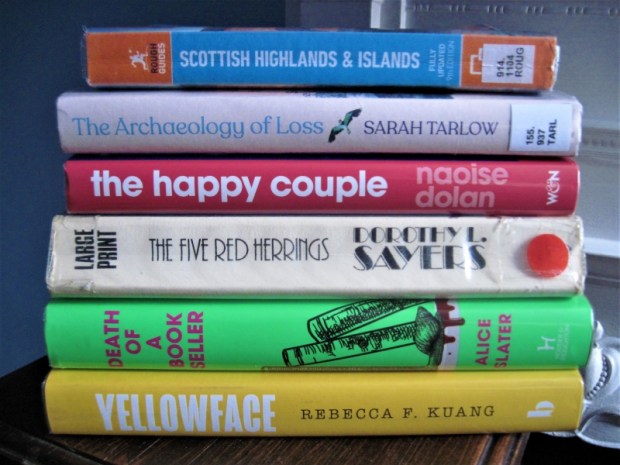

READ

- Rainbow Rainbow: Stories by Lydia Conklin

- The Greengage Summer by Rumer Godden

- Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey

- Scattered Showers: Stories by Rainbow Rowell

- A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye

- Cats in Concord by Doreen Tovey

CURRENTLY READING

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson

- Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

RETURNED UNREAD

- Pod by Laline Paull – I wanted to give this a try because it made the Women’s Prize shortlist, but I looked at the first few pages and skimmed through the rest and knew I just couldn’t take it seriously. I mean, look at lines like these: “The Rorqual wanted to laugh, but it was serious. The dolphin had been in some physical horror and had lost his mind. Google could not bear his mistake. The sound he raced toward was not Base, but this thing, this creature, he had never before encountered.”

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]  If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]