Book Serendipity, January to February

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! Feel free to join in with your own.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An old woman with purple feet (due to illness or injury) in one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Someone is pushed backward and dies of the head injury in Zofia Nowak’s Book of Superior Detecting by Piotr Cieplak and one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff.

- The Hindenburg disaster is mentioned in A Long Game by Elizabeth McCracken and Evensong by Stewart O’Nan.

- Reluctance to cut into a corpse during medical school and the dictum ‘see one, do one, teach one’ in the graphic novel See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor by Grace Farris and Separate by C. Boyhan Irvine.

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

- A mention of genuine Harris tweed in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- The Katharine Hepburn film The Philadelphia Story is mentioned in The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank and Woman House by Lauren W. Westerfield.

- A mention of Icelandic poppies in Nighthawks by Lisa Martin and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Vita Sackville-West is mentioned in the Orlando graphic novel adaptation by Susanne Kuhlendahl and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Fear of bear attacks in Black Bear by Trina Moyles and Boundless by Kathleen Winter. Bears also feature in A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston and No Paradise with Wolves by Katie Stacey. [Looking through children’s picture books at the library the other week, I was struck by how many have bears in the title. Dozens!]

- I was reading books called Memory House (by Elaine Kraf) and Woman House (by Lauren W. Westerfield) at the same time, both of them pre-release books for Shelf Awareness reviews.

- An adolescent girl is completely ignorant of the facts of menstruation in I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman and Carrie by Stephen King.

- Camembert is eaten in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin.

- A herbal tonic is sought to induce a miscarriage in The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley and Bog Queen by Anna North.

- Vicks VapoRub is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson.

- An adolescent girl only admits to her distant mother that she’s gotten her first period because she needs help dealing with a stain (on her bedding / school uniform) in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel, and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin. (I had to laugh at the mother asking the narrator of the Mantel: “Have you got jam on your underskirt?”) Basically, first periods occurred a lot in this set! They are also mentioned in A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman. [I also had three abortion scenes in this cycle, but I think it would constitute spoilers to say which novels they appeared in.)

- A casual job cleaning pub/bar toilets in Kin by Tayari Jones and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Kansas City is a location mentioned in Strangers by Belle Burden, Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, and Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer. (Not actually sure if that refers to Kansas or Missouri in two of them.)

- The notion of “flirting with God” is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht.

- A signature New Orleans cocktail, the Sazerac (a variation on the whisky old-fashioned containing absinthe), appears in Kin by Tayari Jones and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- An older person’s smell brings back childhood memories in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The fact that complaining of chest pain will get you seen right away in an emergency room is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- Thickly buttered toast is a favoured snack in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

- Lime and soda is drunk in Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A husband 17 years older than his wife in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The protagonist seems to hold a special attraction for old men in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A tattoo of a pottery shard (her ex-husband’s) in Strangers by Belle Burden and one of an arrowhead (her own) in Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer.

- A relationship with an older editor at a publishing house: The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank (romantic) and Whistler by Ann Patchett (stepfather–stepdaughter).

- Repeated vomiting and a fever of 103–104°F leads to a diagnosis of appendicitis in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

- Palm crosses are mentioned in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- A Miss Jemison in Kin by Tayari Jones and a Miss Jamieson in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- Pasley as a surname in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael and a place name (Pasley Bay) in Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- A remark on a character’s unwashed hair in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A mention of a monkey’s paw in Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A character gets 26 (22) stitches in her face (head) after a car accident, a young person who’s vehemently anti-smoking, and a mention of being dusted orange from eating Cheetos, in Whistler by Ann Patchett and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Pre-eclampsia occurs in Strangers by Belle Burden and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- There’s a chapter on searching for corncrakes on the Isle of Coll (the Inner Hebrides of Scotland) in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell, which I read last year; this year I reread the essay on the same topic in Findings by Kathleen Jamie.

- Worry over women with long hair being accidentally scalped – if a horse steps on her ponytail in Mare by Emily Haworth-Booth; if trapped in a London Underground escalator in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

- A dodgy doctor who molests a young female patient in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A high school girl’s inappropriate relationship with her English teacher is the basis for Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, and then Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy, which I started soon after.

- College roommates who become same-sex lovers, one of whom goes on to have a heterosexual marriage, in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A mention of Sephora (the cosmetics shop) in Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A discussion of the Greek mythology character Leda in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Whistler by Ann Patchett (where it’s also a character name).

- A workaholic husband who rarely sees his children and leaves their care to his wife in Strangers by Belle Burden and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell.

- An apparently wealthy man who yet steals food in Strangers by Belle Burden and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Characters named Lulubelle in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Lulabelle in Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Characters named Ruth in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Doing laundry at a whorehouse in Kin by Tayari Jones and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A male character nicknamed Doll in John of John by Douglas Stuart and then Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A mention of tuberculosis of the stomach in Findings by Kathleen Jamie and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper. I was also reading a whole book on tuberculosis, Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green, at the same time.

- Mention of Doberman dogs in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman.

- Extreme fear of flying in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

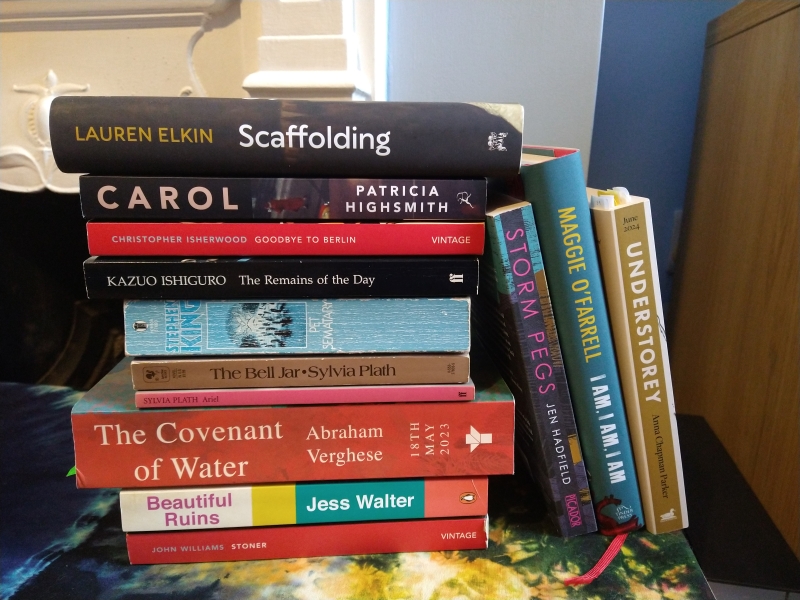

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence and Find Him! (links to my Shelf Awareness reviews) are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-June through August

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A description of the Y-shaped autopsy scar on a corpse in Pet Sematary by Stephen King and A Truce that Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews.

- Charlie Chaplin’s real-life persona/behaviour is mentioned in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus and Greyhound by Joanna Pocock.

- The manipulative/performative nature of worship leading is discussed in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and Jarred Johnson’s essay in the anthology Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia. I read one scene right after the other!

- A discussion of the religious impulse to celibacy in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- Hanif Kureishi has a dog named Cairo in Shattered; Amelia Thomas has a son by the same name in What Sheep Think About the Weather.

- A pilgrimage to Virginia Woolf’s home in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd.

- Water – Air – Earth divisions in the Nature Matters (ed. Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf) and Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthologies.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- Inappropriate sexual comments made to female bar staff in The Most by Jessica Anthony and Isobel Anderson’s essay in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology.

- Charlie Parker is mentioned in The Most by Jessica Anthony and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The metaphor of an ark for all the elements that connect one to a language and culture was used in Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis, which I read earlier in the year, and then again in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- A scene of first meeting their African American wife (one of the partners being a poet) and burning a list of false beliefs in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The Kafka quote “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us” appears in Shattered by Hanif Kureishi and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd. They also both quote Dorothea Brande on writing.

- The simmer dim (long summer light) in Shetland is mentioned in Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield and Sally Huband’s piece in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology (not surprising as they both live in Shetland!).

- A restaurant applauds a proposal or the news of an engagement in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Likeness by Samsun Knight.

- Noticing that someone ‘isn’t there’ (i.e., their attention is elsewhere) in Woodworking by Emily St. James and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and Leaving Church by Barbara Brown Taylor – which involves her literally leaving Atlanta to be the pastor of a country church – at the same time. (I was also reading Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam.)

- A mention of an adolescent girl wearing a two-piece swimsuit for the first time in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han, and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A discussion of John Keats’s concept of negative capability in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A mention of JonBenét Ramsey in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and the new introduction to Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A character drowns in a ditch full of water in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A woman who’s dying of stomach cancer in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A woman’s genitals are referred to as the “mons” in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- A girl doesn’t like her mother asking her to share her writing with grown-ups in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A girl is not allowed to walk home alone from school because of a serial killer at work in the area, and is unprepared for her period so lines her underwear with toilet paper instead in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A character named Stefan in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- A father who is a bad painter in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce.

- The goddess Minerva is mentioned in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A woman finds lots of shed hair on her pillow in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević and The Dig by John Preston.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- The narrator ponders whether she would make a good corpse in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano. The former concludes that she would, while the latter struggles to lie still during savasana (“Corpse Pose”) in yoga – ironic because she has terminal ALS.

- Harry the cat in The Wedding People by Alison Espach; Henry the cat in Calls May Be Recorded by Katharina Volckmer.

- The protagonist has a blood test after rapid weight gain and tiredness indicate thyroid problems in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- It’s said of an island that nobody dies there in Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave by Mariana Enríquez and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- A woman whose mother died when she was young and whose father was so depressed as a result that he was emotionally detached from her in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

- There’s a ghost in the cellar in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević, The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- Mention of harps / a harpist in The Wedding People by Alison Espach, The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce, and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- “You use people” is an accusation spoken aloud in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- Let’s not beat around the bush: “I want to f*ck you” is spoken aloud in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins; “Want to/Wanna f*ck?” is also in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller.

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

- A shawl is given as a parting gift in How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell and one story of What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- The author has Long Covid in Alec Finlay’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and Pluck by Adam Hughes.

- An old woman applies suncream in Kate Davis’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell.

- There’s a leper colony in What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- There’s a missionary kid in South America in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- A teen brother and sister wander the woods while on vacation with their parents in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- Using a famous fake name as an alias for checking into a hotel in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Seascraper by Benjamin Wood.

- A woman punches someone in the chest in the title story of Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Announcing Novellas in November!

Lots of us make a habit of prioritizing novellas in our November reading. (Who can resist that alliteration?) Perhaps you’ve been finding it hard to focus on books with all the bad news around, and your reading target for the year is looking out of reach. If you’re beset by distractions or only have brief bits of free time in your day, short books can be a boon.

In 2018 Laura Frey surveyed the history of Novellas in November, which has had various incarnations but no particular host. This year Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting it as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts. We’ll both put up an opening post on 1 November where you can leave your links throughout the month, to be rounded up on the 30th, and we’ll take turns introducing a theme each Monday.

The definition of a novella is loose – it’s based on word count rather than number of pages – but we suggest aiming for 150 pages or under, with a firm upper limit of 200 pages. Any genre is valid. As author Joe Hill (the son of Stephen King) has said, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” With distinctive characters, intense scenes and sharp storytelling, the best novellas can draw you in for a memorable reading experience – maybe even in one sitting.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Australia Reading Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that count towards multiple challenges? See Cathy’s recent post for ideas of how books can overlap on a few categories. Or you might choose a short Atwood novel, like Surfacing (186 pages) or The Penelopiad (199 pages).

2–8 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas (Rebecca)

16–22 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

23–29 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

We’re looking forward to having you join us! Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and the hashtag #NovNov.

My stacks of possibilities for the four weeks (with a library haul of mostly lit in translation to follow).

Bonus points for three of the below being November review books!

This was among my

This was among my  All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!) This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues. I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (

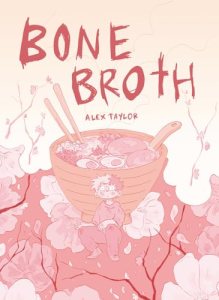

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults ( Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

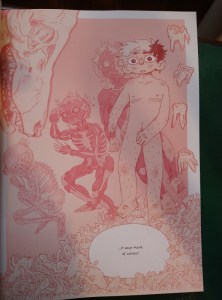

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it. This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent  I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.

The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.  West was a contemporary of F. Scott Fitzgerald; in fact, the story goes that when he died in a car accident at age 37, he had been rushing to Fitzgerald’s wake, and the friends were given adjoining rooms in a Los Angeles funeral home. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” (never given any other name) is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden, the unloved. Not surprisingly, the secondhand woes start to get him down (“his heart remained a congealed lump of icy fat”), and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. Indeed, I was startled by how explicit the language and sexual situations are; this doesn’t feel like a book from 1933. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference really struck me, and the last few chapters, in which a drastic change of life is proffered but then cruelly denied, are masterfully plotted. The 2014 Daunt Books reissue has been given a cartoon cover and a puff from Jonathan Lethem to emphasize how contemporary it feels.