Recent Bylines: Glamour, Shiny New Books, Etc.

Following up on my post from June, here are excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for places that aren’t my blog.

Review essay of Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman for Glamour UK

The female body has been a source of deep embarrassment for Altman, but here she swaps shame for self-deprecating silliness and cringing for chuckling. Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, she exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. While 11 of her 15 topics aren’t exclusive to women’s anatomy—birthmarks, hemorrhoids, warts and more apply to men, too—she always presents an honest account of the female experience. This is one of my favorite books of the year and one I’d recommend to women of any age. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. (My full review is complete with embarrassing personal revelations!)

The female body has been a source of deep embarrassment for Altman, but here she swaps shame for self-deprecating silliness and cringing for chuckling. Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, she exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. While 11 of her 15 topics aren’t exclusive to women’s anatomy—birthmarks, hemorrhoids, warts and more apply to men, too—she always presents an honest account of the female experience. This is one of my favorite books of the year and one I’d recommend to women of any age. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. (My full review is complete with embarrassing personal revelations!)

Essay on two books about “wasting time” for the Los Angeles Review of Books

In Praise of Wasting Time by Alan Lightman  &

&

The Art of the Wasted Day by Patricia Hampl: A poet’s delight in lyricism and free association is in evidence here. The book blends memoir with travel and biographical information about some of Hampl’s exemplars of solitary, introspective living, and it begins, quite literally, with daydreaming.

The Art of the Wasted Day by Patricia Hampl: A poet’s delight in lyricism and free association is in evidence here. The book blends memoir with travel and biographical information about some of Hampl’s exemplars of solitary, introspective living, and it begins, quite literally, with daydreaming.

Hampl and Lightman start from the same point of frazzled frustration and arrive at many of the same conclusions about the necessity of “wasted” time but go about it in entirely different ways. Lightman makes a carefully constructed argument and amasses a sufficient weight of scientific and anecdotal evidence; Hampl drifts and dreams through seemingly irrelevant back alleys of memory and experience. The latter is a case of form following function: her book wanders along with her mind, in keeping with her definition of memoir as “lyrical quest literature,” where meaning always hovers above the basics of plot.

Hampl and Lightman start from the same point of frazzled frustration and arrive at many of the same conclusions about the necessity of “wasted” time but go about it in entirely different ways. Lightman makes a carefully constructed argument and amasses a sufficient weight of scientific and anecdotal evidence; Hampl drifts and dreams through seemingly irrelevant back alleys of memory and experience. The latter is a case of form following function: her book wanders along with her mind, in keeping with her definition of memoir as “lyrical quest literature,” where meaning always hovers above the basics of plot.

Book list for OZY on the refugee crisis & another coming up on compassion in medicine.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reviews

(Their website is not available outside the USA, so the links may not work for you).

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau

Chamoiseau is a social worker and author from the Caribbean island of Martinique. Translator Linda Coverdale has chosen to leave snippets of Martinican Creole in this text, creating a symphony of languages. The novel has an opening that might suit a gloomy fairytale: “In slavery times in the sugar isles, once there was an old black man.” The novel’s language is full of delightfully unexpected verbs and metaphors. At not much more than 100 pages, it is a nightmarish novella that alternates between feeling like a nebulous allegory and a realistic escaped slave narrative. It can be a disorienting experience: like the slave, readers are trapped in a menacing forest and prone to hallucinations. The lyricism of the writing and the brief glimpse back from the present day, in which an anthropologist discovers the slave’s remains and imagines the runaway back into life, give this book enduring power.

Chamoiseau is a social worker and author from the Caribbean island of Martinique. Translator Linda Coverdale has chosen to leave snippets of Martinican Creole in this text, creating a symphony of languages. The novel has an opening that might suit a gloomy fairytale: “In slavery times in the sugar isles, once there was an old black man.” The novel’s language is full of delightfully unexpected verbs and metaphors. At not much more than 100 pages, it is a nightmarish novella that alternates between feeling like a nebulous allegory and a realistic escaped slave narrative. It can be a disorienting experience: like the slave, readers are trapped in a menacing forest and prone to hallucinations. The lyricism of the writing and the brief glimpse back from the present day, in which an anthropologist discovers the slave’s remains and imagines the runaway back into life, give this book enduring power.

Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart

Barry Cohen, a conceited hedge fund manager under SEC investigation for insider trading, sets out on a several-month picaresque road trip in the second half of 2016. The ostensible aim is to find his college girlfriend, but he forms fleeting connections with lots of ordinary folks along the way. Barry may be a figure of fun, but it’s unpleasant to spend so much time with his chauvinism (“he never remembered women’s names” but gets plenty of them to sleep with him), which isn’t fully tempered by alternating chapters from his wife’s perspective. Pitched somewhere between the low point of “Make America Great Again” and the loftiness of the Great American novel, Lake Success may not achieve the profundity it’s aiming for, but it’s still a biting portrait of an all-too-recognizable America where money is God and villains gets off easy.

Barry Cohen, a conceited hedge fund manager under SEC investigation for insider trading, sets out on a several-month picaresque road trip in the second half of 2016. The ostensible aim is to find his college girlfriend, but he forms fleeting connections with lots of ordinary folks along the way. Barry may be a figure of fun, but it’s unpleasant to spend so much time with his chauvinism (“he never remembered women’s names” but gets plenty of them to sleep with him), which isn’t fully tempered by alternating chapters from his wife’s perspective. Pitched somewhere between the low point of “Make America Great Again” and the loftiness of the Great American novel, Lake Success may not achieve the profundity it’s aiming for, but it’s still a biting portrait of an all-too-recognizable America where money is God and villains gets off easy.

Shiny New Books reviews

(Upcoming: Nine Pints by Rose George and Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers.) Latest:

The Immeasurable World: Journeys in Desert Places by William Atkins

Atkins has produced an appealing blend of vivid travel anecdotes, historical background and philosophical musings. He is always conscious that he is treading in the footsteps of earlier adventurers. He has no illusions about being a pioneer here; rather, he eagerly picks up the thematic threads others have spun out of desert experience and runs with them – things like solitude, asceticism, punishment for wrongdoing and environmental degradation. The book is composed of seven long chapters, each set in a different desert. In my favorite segment, the author rents a cabin in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona for $100 a week. My interest waxed and waned from chapter to chapter, but readers of travelogues should find plenty to enjoy. Few of us would have the physical or emotional fortitude to repeat Atkins’s journeys, but we get the joy of being armchair travelers instead.

Atkins has produced an appealing blend of vivid travel anecdotes, historical background and philosophical musings. He is always conscious that he is treading in the footsteps of earlier adventurers. He has no illusions about being a pioneer here; rather, he eagerly picks up the thematic threads others have spun out of desert experience and runs with them – things like solitude, asceticism, punishment for wrongdoing and environmental degradation. The book is composed of seven long chapters, each set in a different desert. In my favorite segment, the author rents a cabin in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona for $100 a week. My interest waxed and waned from chapter to chapter, but readers of travelogues should find plenty to enjoy. Few of us would have the physical or emotional fortitude to repeat Atkins’s journeys, but we get the joy of being armchair travelers instead.

Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens

I was ambivalent about the author’s first book (Bleaker House), but for a student of the Victorian period this was unmissable, and the meta aspect was fun and not off-putting this time. Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. One strand covers the last decade of Gaskell’s life, but what makes it so lively and unusual is that Stevens almost always speaks of Gaskell as “you.” The intimacy of that address ensures her life story is anything but dry. The other chapters are set between 2013 and 2017 and narrated in the present tense, which makes Stevens’s dilemmas feel pressing. For much of the first two years her PhD takes a backseat to her love life. She’s obsessed with Max, a friend and unrequited crush from her Boston University days who is now living in Paris. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

I was ambivalent about the author’s first book (Bleaker House), but for a student of the Victorian period this was unmissable, and the meta aspect was fun and not off-putting this time. Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. One strand covers the last decade of Gaskell’s life, but what makes it so lively and unusual is that Stevens almost always speaks of Gaskell as “you.” The intimacy of that address ensures her life story is anything but dry. The other chapters are set between 2013 and 2017 and narrated in the present tense, which makes Stevens’s dilemmas feel pressing. For much of the first two years her PhD takes a backseat to her love life. She’s obsessed with Max, a friend and unrequited crush from her Boston University days who is now living in Paris. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

Times Literary Supplement reviews

I’ve recently submitted my sixth and seventh for publication. All of them have been behind a paywall so far, alas. (Upcoming: Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul; On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén.) Latest:

How To Build A Boat: A Father, his Daughter, and the Unsailed Sea by Jonathan Gornall

Gornall’s genial memoir is the story of a transformation and an adventure, as a fifty-something freelance journalist gets an unexpected second chance at fatherhood and decides to build his daughter, Phoebe, a boat. It was an uncharacteristic resolution for “a man who [had] never knowingly wielded a plane or a chisel,” yet in a more metaphorical way it made sense: the sea was in his family’s blood. Gornall nimbly conveys the precarious financial situation of the freelancer, as well as the challenges of adjusting to new parenthood late in life. This is a refreshingly down-to-earth account. The nitty-gritty details of the construction will appeal to some readers more than to others, but one can’t help admiring the combination of craftsmanship and ambition. (Full review in September 7th issue.)

Gornall’s genial memoir is the story of a transformation and an adventure, as a fifty-something freelance journalist gets an unexpected second chance at fatherhood and decides to build his daughter, Phoebe, a boat. It was an uncharacteristic resolution for “a man who [had] never knowingly wielded a plane or a chisel,” yet in a more metaphorical way it made sense: the sea was in his family’s blood. Gornall nimbly conveys the precarious financial situation of the freelancer, as well as the challenges of adjusting to new parenthood late in life. This is a refreshingly down-to-earth account. The nitty-gritty details of the construction will appeal to some readers more than to others, but one can’t help admiring the combination of craftsmanship and ambition. (Full review in September 7th issue.)

Heart and Mind: New Nonfiction by Sandeep Jauhar and Jan Morris

Heart: A History, by Sandeep Jauhar

There could hardly be an author better qualified to deliver this thorough history of the heart and the treatment of its problems. Sandeep Jauhar is the director of the Heart Failure Program at Long Island Medical Center. His family history – both grandfathers died of sudden cardiac events in India, one after being bitten by a snake – prompted an obsession with the heart, and he and his brother both became cardiologists. As the book opens, Jauhar was shocked to learn he had up to a 50% blockage of his own coronary vessels. Things had really gotten personal.

Cardiovascular disease has been the #1 killer in the West since 1910 and, thanks to steady smoking rates and a continuing rise in obesity and sedentary lifestyles, will still affect 60% of Americans. However, the key is that fewer people will now die of heart disease thanks to the developments of the last six decades in particular. These include the heart–lung machine, cardiac catheterization, heart transplantation, and artificial hearts.

Along the timeline, Jauhar peppers in bits of his own professional and academic experience, like experimenting on frogs during high school in California and meeting his first cadaver at medical school. My favorite chapter was the twelfth, “Vulnerable Heart,” which is about how trauma can cause heart arrhythmias; it opens with an account of the author’s days cataloguing body parts in a makeshift morgue as a 9/11 first responder. I also particularly liked his account of being called out of bed to perform an echocardiogram, which required catching a taxi at 3 a.m. and avoiding New York City’s rats.

Along the timeline, Jauhar peppers in bits of his own professional and academic experience, like experimenting on frogs during high school in California and meeting his first cadaver at medical school. My favorite chapter was the twelfth, “Vulnerable Heart,” which is about how trauma can cause heart arrhythmias; it opens with an account of the author’s days cataloguing body parts in a makeshift morgue as a 9/11 first responder. I also particularly liked his account of being called out of bed to perform an echocardiogram, which required catching a taxi at 3 a.m. and avoiding New York City’s rats.

Maybe I’ve read too much surgical history this year (The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris and Face to Face by Jim McCaul), though, because I found myself growing fairly impatient with the medical details in the long Part II, which centers on the heart as a machine, and was drawn more to the autobiographical material in the first and final sections. Perhaps I would prefer Jauhar’s first book, Intern: A Doctor’s Initiation.

In terms of readalikes, I’d mention Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene, in which the personal story also takes something of a backseat to the science, and Gavin Francis’s Shapeshifters, which exhibits a similar interest in the metaphors applied to the body. While I didn’t enjoy this quite as much as two other heart-themed memoirs I’ve read, The Sanctuary of Illness by Thomas Larson and Echoes of Heartsounds by Martha Weinman Lear, I still think it’s a strong contender for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize (the judging panel is announced tomorrow!).

Some favorite lines:

“it is increasingly clear that the biological heart is extraordinarily sensitive to our emotional system—to the metaphorical heart, if you will.”

“Who but the owner can say what lies inside a human heart?”“As a heart-failure specialist, I’d experienced enough death to fill up a lifetime. At one time, it was difficult to witness the grief of loved ones. But my heart had been hardened, and this was no longer that time.”

My rating:

Heart is published in the UK today, September 27th, by Oneworld. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

In My Mind’s Eye: A Thought Diary, by Jan Morris

I’ve been an admirer of Jan Morris’s autobiographical and travel writing for 15 years or more. In this diary covering 2017 into early 2018, parts of which were originally published in the Financial Times and the Welsh-language literary newspaper O’r Pedwar Gwynt, we get a glimpse into her life in her early nineties. It was a momentous time in the world at large but a fairly quiet and reflective span for her personally. Though each day’s headlines seem to herald chaos and despair, she’s a blithe spirit – good-natured about the ravages of old age and taking delight in the routines of daily one-mile walks down the lane and errands in local Welsh towns with her beloved partner Elizabeth, who’s in the early stages of dementia.

There are thrilling little moments, though, when a placid domestic life (a different kind of marmalade with breakfast each day of the week!) collides with exotic past experiences, and suddenly we’re plunged into memories of travels in Swaziland and India. Back when she was still James, Morris served in World War II, was the Times journalist reporting from the first ascent of Everest, and wrote a monolithic three-volume history of the British Empire. She took her first airplane flight 70 years ago, and is nostalgic for the small-town America she first encountered in the 1950s. Hold all that up against her current languid existence among the books and treasures of Trefan Morys and it seems she’s lived enough for many lifetimes.

There are thrilling little moments, though, when a placid domestic life (a different kind of marmalade with breakfast each day of the week!) collides with exotic past experiences, and suddenly we’re plunged into memories of travels in Swaziland and India. Back when she was still James, Morris served in World War II, was the Times journalist reporting from the first ascent of Everest, and wrote a monolithic three-volume history of the British Empire. She took her first airplane flight 70 years ago, and is nostalgic for the small-town America she first encountered in the 1950s. Hold all that up against her current languid existence among the books and treasures of Trefan Morys and it seems she’s lived enough for many lifetimes.

There’s a good variety of topics here, ranging from current events to Morris’s love of cats; I particularly liked the fragments of doggerel. However, as is often the case with diaries, read too many entries in one go and you may start to find the sequence of (non-)events tedious. Each piece is only a page or two, so I tried never to read many more than 10 pages at a time. Even so, I noticed that the plight of zoo animals, clearly a hobby-horse, gets mentioned several times. It seemed to me a strange issue to get worked up about, especially as enthusiastic meat-eating and killing mice with traps suggest that she’s not applying a compassionate outlook consistently.

In the end, though, kindness is Morris’s cardinal virtue, and despite minor illness, telephone scams and a country that looks to be headed to the dogs, she’s encouraged by the small acts of kindness she meets with from friends and strangers alike. Like Diana Athill (whose Alive, Alive Oh! this resembles), I think of Morris as a national treasure, and I was pleased to spend some time seeing things from her perspective.

Some favorite lines:

“If I set out in the morning for my statutory thousand daily paces up the lane, … I enjoy the fun of me, the harmless conceit, the guileless complexity and the merriment. When I go walking in the evening, on the other hand, … I shall recognize what I don’t like about myself – selfishness, self-satisfaction, foolish self-deceit and irritability. Morning pride, then, and evening shame.” (from Day 99)

“Good or bad, virile or senile, there’s no life like the writer’s life.” (from Day 153)

My rating:

In My Mind’s Eye was published by Faber & Faber on September 6th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

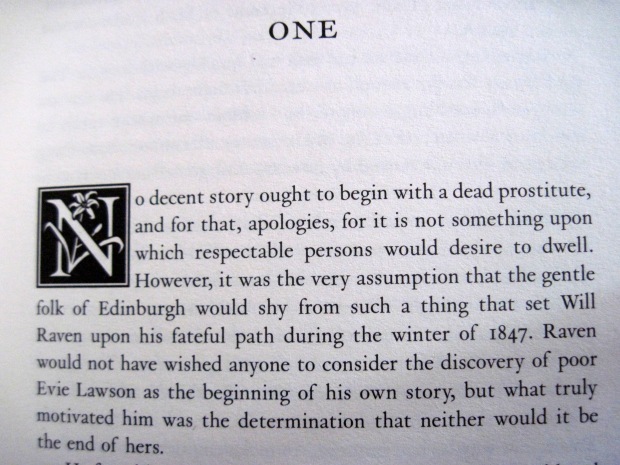

The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry

This historical novel set in Edinburgh in 1847 has one of the best opening paragraphs I’ve come across in a while:

That immediately sets the tone: realistic, sly, and somewhat seedy. If the title sounds familiar, it’s because it’s borrowed from Samuel Butler’s gloomy 1903 meditation on sin and salvation in several generations of a Victorian family. I remember trudging through it on a weekend break to Strasbourg during my year abroad.

Parry (a pseudonym for husband–wife duo Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) uses the allusion to highlight the hidden sins of the Victorian period and hint at the fleshy concerns of their book, which contains somewhat gruesome scenes of childbirth and surgery. Ether and chloroform were recent introductions and many were still apprehensive about them or even opposed to their use on religious grounds, as Haetzman, a consultant anesthetist, learned while researching for her Master’s degree in the History of Medicine.

Parry (a pseudonym for husband–wife duo Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) uses the allusion to highlight the hidden sins of the Victorian period and hint at the fleshy concerns of their book, which contains somewhat gruesome scenes of childbirth and surgery. Ether and chloroform were recent introductions and many were still apprehensive about them or even opposed to their use on religious grounds, as Haetzman, a consultant anesthetist, learned while researching for her Master’s degree in the History of Medicine.

Into this milieu enters Will Raven, the new apprentice to Dr. Simpson, a professor of midwifery. Will is troubled by the recent loss of his friend Evie Lawson, the dead prostitute of the first paragraph, and wonders if she could have been poisoned by some bad moonshine. Only as he hears rumors about a local abortionist – no better than a serial killer – who’s been giving women quack pills and potions, followed by rudimentary operations that leave them to die of peritonitis, does he begin to wonder if Evie could have been pregnant when she died.

The novel peppers in lots of period slang and details about homeopathy, phrenology and early photography. Best of all, it has a surprise heroine: the Simpsons’ maid, Sarah Fisher, who keeps shaming Will with her practical medical know-how and ends up being something of a sidekick in his investigations. She wants to work as a druggist’s assistant, but the druggist insists that only a man can do the job. Dr. Simpson recognizes that the housemaid’s role is rather a waste of Sarah’s talents and expresses his hope that she’ll seek to be part of a widespread change for women.

The Way of All Flesh is sure to appeal to readers of Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White and Steven Price’s By Gaslight. It’s not quite as rewarding as the former, but the length and style make it significantly more engaging than the latter. It also serves as a good fictional companion to Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art; for that reason, I wouldn’t be surprised to see it appear on next year’s Wellcome Book Prize longlist.

Victorian Edinburgh on the endpapers.

Favorite lines:

“That was Edinburgh for you: public decorum and private sin, city of a thousand secret selves.”

“‘Simpson likes to think of medicine as more than pure science,’ [Raven] countered. ‘There must also be empathy, concern, a human connection.’ ‘I suggest that both elements are required,’ offered Henry. ‘Scientific principles married to creativity. Science and art.’ If it is an art, it is at times a dark one, Raven thought, though he chose to keep this observation to himself.”

My rating:

The Way of All Flesh comes out today, August 30th, in the UK. It was published in the States by HarperCollins on the 28th. My thanks to Canongate for sending a free copy for review.

Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist Event

Five of the six shortlisted authors (barring Dublin-based Mark O’Connell) were at the Wellcome Collection in London yesterday to share more about their books in mini-interviews with Lisa O’Kelly, the associate editor of the Observer. She called each author up onto the stage in turn for a five-minute chat about her work, and then brought them all up for a general conversation and audience questions. Clare and I found it a very interesting afternoon. Here’s some context that I gleaned about the five books and their writers.

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Sigrid Rausing started writing her book soon after her sister-in-law Eva’s body was found: just random paragraphs to make sense of what had happened. From there it became an investigation, a quest to find the nature of addiction. She thinks that as a society we still don’t quite understand what addiction is, and the medical research and public perception are very separate. In addition to nature and nurture, she thinks we should consider the influence of culture – as an anthropologist by training, she’s very interested in drug culture and how that drew in her brother, Hans. Although there have been many memoirs by ex-addicts, she can’t think of another one by a family member. Perhaps, she suggested, this is because the addict is seen as the ultimate victim. She referred to her book as a “collage,” a very apt description.

Kathryn Mannix spoke of how her grandmother, born in 1900, saw so much more death than we do nowadays: siblings, a child, and so on. Today, though, Mannix has encountered people in their sixties who are facing, with their parents, their very first deaths. Death is fairly “gentle” and “dull” if you’re not directly involved, she insists; she blames Hollywood and Eastenders for showing unusually dramatic deaths. She said once you understand what exactly people are afraid of about dying (e.g. hell, oblivion, pain, leaving their families behind) you can address their specific concerns and thereby “beat out the demon of terror and fear.” Mannix never intended to write a book, but someone heard her on the radio and invited her to do so. Luckily, from her medical school days onward, she’d been writing an A4 page about each of her most mind-boggling cases to get them out of her head and move on. That’s why, as O’Kelly put it, the characters in her 30 stories “leap off the page.”

Mannix, Adebayo, O’Kelly, Rausing, Wadman & Fitzharris

Lindsey Fitzharris called The Butchering Art “a love story between science and medicine” – it was the first time that the former (antisepsis) was applied to the latter. She initially thought Robert Liston was her man – he was so colorful, larger than life – but eventually found that the real story was with Joseph Lister, the quiet, persistent Quaker. (However, the book does open with Liston performing the first surgery under ether.) Fitzharris is also involved in the Order of the Good Death, author Caitlin Doughty’s initiative, and affirmed Mannix’s efforts to remove the taboo from talking about death. I think I heard correctly that she said there is a film of The Butchering Art in the works?! I’ll need to look into that some more.

Meredith Wadman started with a brief explanation of how immunization works and why the 1960s were ripe for vaccine research. This segment went really science-y, which I thought was a little unfortunate as it may have made listeners tune out and be less interested in her work than the others’. It was perhaps inevitable given her subject matter, but also a matter of the questions O’Kelly asked – with the others she focused more on stories and themes than on scientific facts. It was interesting to hear what Wadman has been working on recently: for the past 6–8 months, she’s been reporting for Science on sexual harassment in science. For her next book, though, she’s pondering the conflict between a congressman and a Centers for Disease Control scientist over funding into research that might lead to gun control.

The question time brought up the issues of medical misinformation online, the distrust people with chronic illnesses have of medical professionals, and euthanasia – Mannix rather dodged that one, stating that her book is about the natural dying process so that’s not really her area. (Though it does come up in a chapter of her book.) We also heard a bit about the projects up next for each author. Rausing’s next book will be a travel memoir about the Capetown drought, taking in apartheid and her husband’s family’s immigration. Adebayo is at work on a very nebulous novel “about people,” and possibly how privilege affects access to healthcare.

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel Decision

Addiction, death, infertility, surgery, transhumanism and vaccines: It’s been quite the varied reading list for the five of us this spring! Lots of science, lots of medicine, but also a lot of stories and imagination.

After some conferring and voting, we have arrived at our shadow panel winner for the Wellcome Book Prize 2018: To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell.

Rarely have I been so surprised to love a book. It’s a delight to read, and no matter what your background or beliefs are, it will give you plenty to think about. It goes deep down, beneath our health and ultimately our mortality, to ask what the essence of being human is.

Here’s what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about our pick:

Annabel: “O’Connell, as a journalist and outsider in the surprisingly diverse field of transhumanism, treats everyone with respect: asking the questions, but not judging, to get to the heart of the transhumanists’ beliefs. For a subject based in technology, To Be a Machine is a profoundly human story.”

Clare: “The concept of transhumanism may not be widely known or understood yet, but O’Connell’s engaging and fascinating book explains the significance of the movement and its possible implications both in the distant future and how we live now.”

Laura: “My brain feels like it’s been wired slightly differently since reading To Be a Machine. It’s not just about weird science and weird scientists, but how we come to terms with the fact that even the luckiest of us live lives that are so brief.”

Paul: “An interesting book that hopefully will provoke further discussion as we embrace technology and it envelops us.”

On Monday we’ll find out which book the official judges have chosen. I could see three or four of these as potential winners, so it’s very hard to say who will take home the £30,000.

Who are you rooting for?

One More Wellcome Longlist Review & Shortlist Predictions

Tomorrow the six titles on the Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be revealed. I’ve managed to read one more from the longlist since my last batch.

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine by Lindsey Fitzharris

Surgery was a gory business with a notably high fatality rate well into the nineteenth century. Surgeons had the fastest hands in the West, but their victims were still guaranteed at least a few minutes of utter agony as they had a limb amputated or a tumor removed, and the danger wasn’t over after they were sewn up either: most patients soon died from hospital infections. The development of anesthetics and antiseptic techniques helped to change all that.

Surgery was a gory business with a notably high fatality rate well into the nineteenth century. Surgeons had the fastest hands in the West, but their victims were still guaranteed at least a few minutes of utter agony as they had a limb amputated or a tumor removed, and the danger wasn’t over after they were sewn up either: most patients soon died from hospital infections. The development of anesthetics and antiseptic techniques helped to change all that.

Fitzharris opens with the vivid and rather gruesome scene of a mid-thigh amputation performed by Robert Liston at University College Hospital in London in 1846. This surgery was different, though: it only took 28 seconds, but the patient felt nothing thanks to the ether he had been administered. He woke up a few minutes later asking when the procedure would begin. In the audience that day was Joseph Lister, who would become one of Britain’s most admired surgeons.

Lister came from a Quaker family and, after being educated at University College London, started his career in Edinburgh. Different to many medical professionals of the time, he was fascinated by microscopy and determined to find out what caused deadly infections. Carbolic acid and catgut ligatures were two of Lister’s main innovations that helped to fight infection. In fact, whether we realize it or not, his legacy is forever associated with antiseptics: Listerine mouthwash (invented in 1879) is named after him, and the Johnson brothers of Johnson & Johnson fame started their business mass-producing sterile surgical dressings after attending one of Lister’s lectures.

My interest tailed off a bit after the first third, as the book starts going into more depth about Lister’s work and personal life: he married his boss’s daughter and moved from Edinburgh to Glasgow and then back to London. However, the best is yet to come: the accounts of the surgeries he performed on his sister (a mastectomy that bought her three more years of life) and Queen Victoria (removing an orange-sized abscess from under her arm) are terrific. The chapter on treating the queen in secret at Balmoral Castle in 1871 was my overall favorite.

It probably wasn’t the best idea to start this book over my lunch one day!

I was that kid who loved going to Civil War battlefields and medical museums and looking at all the different surgical saws and bullet fragments in museum cases, so I reveled in the gory details here but was not as interested in the biographical material. Do be sure you have a strong stomach before you try reading the prologue over a meal. This is a comparable read to The Remedy, about the search for a cure to tuberculosis.

My rating:

Shortlist Predictions

Now, I’ve still only read half of the longlisted titles so far, so it’s hard to make any solid guesses. However, the below fall somewhere between wishes and informed predictions:

- In Pursuit of Memory by Joseph Jebelli: A definitive treatment of an epidemic of our time, Alzheimer’s disease. The neuroscientist author achieves the right balance between history and research on the one hand and personal stories readers can relate to on the other.

- The White Book by Han Kang: The only fiction title from the longlist that I haven’t read at least part of. This is also on this year’s Man Booker International Prize longlist and has been well received. From what I can tell, the health theme seems stronger than that of Stay with Me or Midwinter Break, and it would also be nice for one title in translation to make the shortlist.

- With the End in Mind by Kathryn Mannix: As I said in my review last week, this is an excellent all-round guide to preparation for death, based around touching patient stories plus the author’s experience in palliative care and CBT. Practical, compassionate and helpful.

- I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell: For me, this book stands out as the one that most clearly illuminates the effects of illness, medical treatment, and other threats to life and limb in the course of an ordinary existence. I’d be very happy to see it win the whole thing.

- EITHER The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris OR The Vaccine Race by Meredith Wadman: I reckon one history of science title deserves to be on there; I think Wadman might have the slight edge.

- EITHER To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell OR Behave by Robert Sapolsky: The Wellcome Prize loves big books investigating human tendencies and possibilities. I find the thought of either of these daunting, but I know they would also be illuminating. I’d prefer to read the O’Connell, but I’d give the edge to Sapolsky.

Any predictions of your own to make?

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel & Two Longlist Reviews

I’m delighted to announce the other book bloggers on my Wellcome Book Prize 2018 shadow panel: Paul Cheney of Halfman, Halfbook, Annabel Gaskell of Annabookbel, Clare Rowland of A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall. Once the shortlist is announced on Tuesday the 20th, we’ll be reading through the six nominees and sharing our thoughts. Before the official winner is announced at the end of April we will choose our own shadow winner.

I’ve been working my way through some of the longlisted titles I was able to access via the public library and NetGalley. Here’s my latest two (both  ):

):

Plot 29: A Memoir by Allan Jenkins

This is an unusual hybrid memoir: it’s a meditative tour through the gardening year, on a plot in London and at his second home in his wife’s native Denmark. But it’s also the story of how Jenkins, editor of the Observer Food Monthly, investigated his early life. Handed over to a Barnardo’s home at a few months of age, he was passed between various family members and a stepfather (with some degree of neglect: his notes show scabies, rickets and TB) and then raised by strict foster parents in Devon with his beloved older half-brother, Christopher. It’s interesting to read that initially Jenkins intended to write a simple gardening diary, with a bit of personal stuff thrown in. But as he got further into the project, it started to morph.

This cover image is so sweet. It’s a photograph from Summer 1959 of Christopher and Allan (on the right, aged five), just after they were taken in by their foster parents in Devon.

The book has a complicated chronology: though arranged by month, within chapters its fragments jump around in time, a year or a date at the start helping the reader to orient herself between flashbacks and the contemporary story line. Sections are often just a paragraph long; sometimes up to a page or two. I suspect some will find the structure difficult and distancing. It certainly made me read the book slowly, which I think was the right way. You take your time adjusting to the gradual personal unveiling just as you do to the slow turn of the seasons. When major things do happen – meeting his mother in his 30s; learning who his father was in his 60s – they’re almost anticlimactic, perhaps because of the rather flat style. It’s the process that has mattered, and gardening has granted solace along the way.

I’m grateful to the longlist for making me aware of a book I otherwise might never have heard about. I don’t think the book’s mental health theme is strong enough for it to make the shortlist, but I enjoyed reading it and I’ll also take a look at Jenkins’s upcoming book, Morning, about the joys of being an early riser. (Ironic after my recent revelations about my own sleep patterns!)

Favorite lines:

“Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment”

“The last element to be released from Pandora’s box, they say, was hope. So I will mourn the children we once were and I will sow chicory for bitterness. I will plant spring beans and alliums. I’ll look after them.”

“As a journalist, I have learned the five Ws – who, what, where, when, why. They are all needed to tell a story, we are taught, but too many are missing in my tale.”

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial by Kathryn Mannix

This is an excellent all-round guide to preparation for death. It’s based around relatable stories of the patients Mannix met in her decades working in the fields of cancer treatment and hospice care. She has a particular interest in combining CBT with palliative care to help the dying approach their remaining time with realism rather than pessimism. In many cases this involves talking patients and their loved ones through the steps of dying and explaining the patterns – decreased energy, increased time spent asleep, a change in breathing just before the end – as well as being clear about how suffering can be eased.

I read the first 20% on my Kindle and then skimmed the rest in a library copy. This was not because I wasn’t enjoying it, but because it was a two-week loan and I was conscious of needing to move on to other longlist books. It may also be because I have read quite a number of books with similar themes and scope – including Caitlin Doughty’s two books on death, Caring for the Dying by Henry Fersko-Weiss, Being Mortal by Atul Gawande, and Waiting for the Last Bus by Richard Holloway. Really this is the kind of book I would like to own a copy of and read steadily, just a chapter a week. Mannix’s introductions to each section and chapter, and the Pause for Thought pages at the end of each chapter, mean the book lends itself to being read as a handbook, perhaps in tandem with an ill relative.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

Mannix believes there’s something special about people who are approaching the end of their life. There’s wisdom, dignity, even holiness surrounding them. It’s clear she feels she’s been honored to work with the dying, and she’s helped to propagate a healthy approach to death. As her children told her when they visited her dying godmother, “you and Dad [a pathologist] have spent a lifetime preparing us for this. No one else at school ever talked about death. It was just a Thing in our house. And now look – it’s OK. We know what to expect. We don’t feel frightened. We can do it. This is what you wanted for us, not to be afraid.”

I would be happy to see this advance to the shortlist.

Favorite lines:

“‘So, how long has she got?’ I hate this question. It’s almost impossible to answer, yet people ask as though it’s a calculation of change from a pound. It’s not a number – it’s a direction of travel, a movement over time, a tiptoe journey towards a tipping point. I give my most honest, most direct answer: I don’t know exactly. But I can tell you how I estimate, and then we can guesstimate together.”

“we are privileged to accompany people through moments of enormous meaning and power; moments to be remembered and retold as family legends and, if we get the care right, to reassure and encourage future generations as they face these great events themselves.”

Longlist strategy:

Currently reading: The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris: a history of early surgery and the fight against hospital infection, with a focus on the life and work of Joseph Lister.

Up next: I’ve requested review copies of The White Book by Han Kang and Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, but if they don’t make it to the shortlist they’ll slip down the list of priorities.

Brain vs. Heart Surgery: Admissions and Fragile Lives

It’s never too early to start thinking about which books might make it onto next year’s Wellcome Book Prize nominees list, open to any medical-themed books published in the UK in calendar year 2017. I’ve already read some cracking contenders, including these two memoirs from British surgeons.

Brain surgeon Henry Marsh’s first book, Do No Harm, was one of my favorite reads of 2015. In short, enthrallingly detailed chapters named after conditions he had treated or observed, he reflected on life as a surgeon, expressing sorrow over botched operations and marveling at the God-like power he wields over people’s quality of life. That first memoir saw him approaching retirement age and nearing the end of his tether with NHS bureaucracy.

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery serves as a sort of sequel, recording Marsh’s last few weeks at his London hospital and the projects that have driven him during his first years of retirement: woodworking, renovating a derelict lock-keeper’s cottage by the canal in Oxford, and yet more neurosurgery on medical missions to Nepal and the Ukraine. But he also ranges widely over his past, recalling cases from his early years in medicine as well as from recent memory, and describing his schooling and his parents. If I were being unkind, I might say that this feels like a collection of leftover incidents from the previous book project.

However, the life of a brain surgeon is so undeniably exciting that, even if these stories are the scraps, they are delicious ones. The title has a double meaning, of course, referring not only to the patients who are admitted to the hospital but also to a surgeon’s confessions. And there are certainly many cases Marsh regrets, including operating on the wrong side in a trapped nerve patient, failing to spot that a patient was on the verge of a diabetic coma before surgery, and a young woman going blind after an operation in the Ukraine. Often there is no clear right decision, though; operating or not operating could lead to equal damage.

Once again I was struck by Marsh’s trenchant humor: he recognizes the absurdities as well as the injustices of life. In Houston he taught on a neurosurgery workshop in which students created and then treated aneurysms in live pigs. When asked “Professor, can you give us some surgical pearls?” he “thought a little apologetically of the swine in the nearby bay undergoing surgery.” A year or so later, discussing the case of a twenty-two-year-old with a fractured spine, he bitterly says, “Christopher Reeve was a millionaire and lived in America and he eventually died from complications, so what chance a poor peasant in Nepal?”

Although some slightly odd structural decisions have gone into this book – the narrative keeps jumping back to Nepal and the Ukraine, and a late chapter called “Memory” is particularly scattered in focus – I still thoroughly enjoyed reading more of Marsh’s anecdotes. The final chapter is suitably melancholy, with its sense of winding down capturing not just the somewhat slower pace of his retired life but also his awareness of the inevitable approach of death. Recalling two particularly hideous deaths he observed in his first years as a doctor, he lends theoretical approval for euthanasia as a way of maintaining dignity until the end.

What I most admire about Marsh’s writing is how he blends realism and wonder. “When my brain dies, ‘I’ will die. ‘I’ am a transient electrochemical dance, made of myriad bits of information,” he recognizes. But that doesn’t deter him from producing lyrical passages like this one: “The white corpus callosum came into view at the floor of the chasm, like a white beach between two cliffs. Running along it, like two rivers, were the anterior cerebral arteries, one on other side, bright red, pulsing gently with the heartbeat.” I highly recommend his work to readers of Atul Gawande and Paul Kalanithi.

My rating:

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery was published in the UK by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on May 4th. My thanks to the publisher for sending a free copy for review. It will be published in the USA by Thomas Dunne Books on October 3rd.

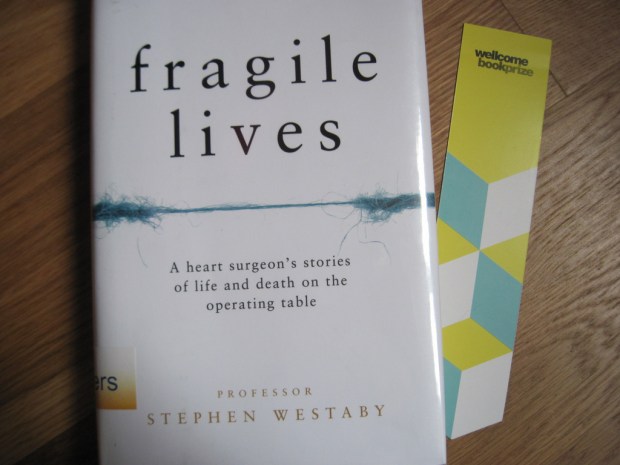

What Marsh does for brain surgery in his pair of memoirs, Professor Stephen Westaby does for heart surgery in Fragile Lives, a vivid, compassionate set of stories culled from his long career. A working class lad from Scunthorpe who watched his grandfather die of heart failure, he made his way up from hospital porter to world-leading surgeon after training at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School.

Each of these case studies, from a young African mother and her sick child whom he met while working in Saudi Arabia in the 1980s to a university student who collapses not far from his hospital in Oxford, is told in impressive depth. Although the surgery details are not for the squeamish, I found them riveting. Westaby conveys a keen sense of the adrenaline rush a surgeon gets while operating with the Grim Reaper looking on. I am not a little envious of all that he has achieved: not just saving the occasional life despite his high-mortality field – as if that weren’t enough – but also pioneering various artificial heart solutions and a tracheal bypass tube that’s named after him.

Like Marsh, he tries not to get emotionally attached to his patients, but often fails in this respect. “Surgeons are meant to be objective, not human,” he shrugs. But, also like Marsh, at his retirement he feels that NHS bureaucracy has tied his hands, denying necessary funds and equipment. Both authors come across as mavericks who don’t play by the rules, but save lives anyway. This is a fascinating read for anyone who enjoys books on a medical theme.

A few favorite lines:

“We stop life and start it again, making things better, taking calculated risks.”

“We were adrenaline junkies living on a continuous high, craving action. From bleeding patients to cardiac arrests. From theatre to intensive care. From pub to party.”

My rating:

Fragile Lives: A Heart Surgeon’s Stories of Life and Death on the Operating Table was published in the UK by HarperCollins on February 9th. I read a public library copy. It will be published in the USA, by Basic Books, under the title Open Heart on June 20th.

It’s not a place for the squeamish as there are mummified skeletons, details about Burke and Hare’s grave-robbing, surgical tools, and tumors and other anatomical deformities in jars everywhere. I found it all fascinating and spent a good two hours poking around. My favorite bits were the case full of foreign bodies removed from noses, stomachs and intestines and the temporary exhibition, “A Quest for Healing” by Zhang Yanzi, who had a residency at the museums in the summer of 2017. Her pieces included a 2D mountain made of pill packets, a cotton and gauze sculpture bristling with acupuncture needles, a matching hanging sculpture of capillaries, two surgical beds, and various silk screen panels.

It’s not a place for the squeamish as there are mummified skeletons, details about Burke and Hare’s grave-robbing, surgical tools, and tumors and other anatomical deformities in jars everywhere. I found it all fascinating and spent a good two hours poking around. My favorite bits were the case full of foreign bodies removed from noses, stomachs and intestines and the temporary exhibition, “A Quest for Healing” by Zhang Yanzi, who had a residency at the museums in the summer of 2017. Her pieces included a 2D mountain made of pill packets, a cotton and gauze sculpture bristling with acupuncture needles, a matching hanging sculpture of capillaries, two surgical beds, and various silk screen panels.

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne is a delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view – first Erich Ackerman, whose Nazi-era history provides the basis for Maurice’s first novel; then Gore Vidal, to whose Italian home Maurice pays a visit with his new mentor; and finally Maurice’s wife Edith, a celebrated author in her own right – before getting Maurice’s own perspective. By this point we know enough about him to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. My one criticism is that I would have binned the whole subplot about Edith’s sister and brother-in-law. (A nice touch: at one point Maurice buys a reprint copy of Maude Avery’s Like to the Lark, which should ring a bell from

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne is a delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view – first Erich Ackerman, whose Nazi-era history provides the basis for Maurice’s first novel; then Gore Vidal, to whose Italian home Maurice pays a visit with his new mentor; and finally Maurice’s wife Edith, a celebrated author in her own right – before getting Maurice’s own perspective. By this point we know enough about him to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. My one criticism is that I would have binned the whole subplot about Edith’s sister and brother-in-law. (A nice touch: at one point Maurice buys a reprint copy of Maude Avery’s Like to the Lark, which should ring a bell from  I also read over half of Jenny Diski’s Stranger on a Train, a memoir about two long train journeys she took across America in the late 1990s that also incorporates memories from a troubled adolescence – she started smoking at 14 and was in and out of mental hospitals at 15 – in which she loved nothing more than to read while riding the Circle line all day long. I’m a quarter of the way through both Nancy Horan’s Under the Wide and Starry Sky, about Stevenson and his wife, and Peter Hill’s Stargazing, a memoir about dropping out of art school to become a Scottish lighthouse keeper in 1973; he started on Pladda, a tiny island off of Arran. And on my Nook I read a good bit of All You Can Ever Know, Nicole Chung’s forthcoming memoir about being raised by adoptive white parents in Oregon and meeting members of her Korean family in her mid-twenties, just as she became a mother herself.

I also read over half of Jenny Diski’s Stranger on a Train, a memoir about two long train journeys she took across America in the late 1990s that also incorporates memories from a troubled adolescence – she started smoking at 14 and was in and out of mental hospitals at 15 – in which she loved nothing more than to read while riding the Circle line all day long. I’m a quarter of the way through both Nancy Horan’s Under the Wide and Starry Sky, about Stevenson and his wife, and Peter Hill’s Stargazing, a memoir about dropping out of art school to become a Scottish lighthouse keeper in 1973; he started on Pladda, a tiny island off of Arran. And on my Nook I read a good bit of All You Can Ever Know, Nicole Chung’s forthcoming memoir about being raised by adoptive white parents in Oregon and meeting members of her Korean family in her mid-twenties, just as she became a mother herself.