20 Books of Summer, 13–16: Tony Chan, Jen Hadfield, Kenward Anthology, Catherine Taylor

Three from my initial list (all nonfiction) and one substitute picked up at random (poetry). These are strongly place-based selections, ranging from Sheffield to Shetland and drawing on travels while also commenting on how gender and dis/ability affect daily life as well as the experience of nature.

Four Points Fourteen Lines by Tony Chan (2016)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library) ![]()

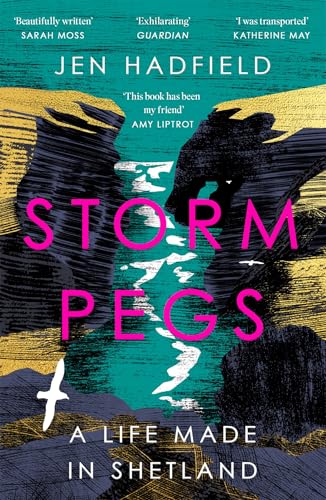

Storm Pegs: A Life Made in Shetland by Jen Hadfield (2024)

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place.

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free paperback copy for review.

From Shetland authors, I have also reviewed:

Orchid Summer by Jon Dunn (Hadfield mentions him)

Sea Bean by Sally Huband (Hadfield meets her)

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, ed. Louise Kenward (2023)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list) ![]()

The Stirrings: Coming of Age in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor (2023)

“A typical family and an ordinary story, although neither the family nor the story seems commonplace when it is your family and your story.”

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token)

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token) ![]()

The Bookshop Band in Abingdon & 20 Books of Summer, 6: Orphans of the Carnival by Carol Birch

The Bookshop Band have been among my favourite musical acts since I first saw play live at the Hungerford Literary Festival in 2014. Initially formed of three local musicians for hire, they got their start in 2010 as the house band at Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, England. For their first four years, they wrote a pair of original songs about a new book, often the very day of an author’s event in the shop, and performed them on guitar, cello, and ukulele as an interlude to the evening’s reading and discussion.

Notable songs from their first 13 albums are based on Glow by Ned Beauman (“We Are the Foxes”), Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller (“Bobo and the Cattle”), The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Rachel Joyce (“How Not to Woo a Woman”), and Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel (“You Make the Best Plans, Thomas”). They have also written responses to classic literature, with songs inspired by Alice in Wonderland, various Shakespeare plays, and a compilation of first lines called “Once Upon a Time.”

I got to see the band live five times pre-pandemic, even after husband-and-wife-duo Ben Please and Beth Porter moved nearly 400 miles away to Wigtown, the Book Town of Scotland. During the first six months of Covid-19 lockdown, the livestream concerts from their attic were weekly treats to look forward to. They also interviewed authors for a breakfast chat show as part of the Wigtown Book Festival, which went online that year.

In the years since, the band has kept busy with other projects (not to mention two children). Porter sings and performs on the two Spell Songs albums based on Robert Macfarlane’s The Lost Words and its sequel. Together they composed the soundtrack to Aardman Animations’ short film, Robin Robin (2021) – winning Best Music at the British Animation Awards, and wrote an album of songs based on Scottish children’s literature. And they have continued writing one-off book songs, such as for the launch of Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton. (I’m disappointed their songs about All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and The Spinning Heart by Donal Ryan still haven’t made it onto record.)

I’ve been enthusing about them for nearly a decade, but they’ve remained mostly under the radar in that time. Not so any longer; their recent album Emerge, Return was produced by Pete Townshend of The Who; the production value has notably advanced while retaining their indie spirit. Foreword Reviews kindly agreed to pay me to fangirl – er, write a blog – about Emerge, Return and the tour supporting it, so I’ll leave it there for the music criticism (their complete discography is now available on Bandcamp and Spotify). I’ll just add that a number of these ‘new’ songs have been kicking around for six to ten years but went unrecorded until now. For that reason, I worried that it might feel like a collection of cast-offs, but in fact they’ve managed to produce something sonically and thematically cohesive. It’s darker than some of their previous work, with moody minor chords and slightly sinister subjects.

I’ve been enthusing about them for nearly a decade, but they’ve remained mostly under the radar in that time. Not so any longer; their recent album Emerge, Return was produced by Pete Townshend of The Who; the production value has notably advanced while retaining their indie spirit. Foreword Reviews kindly agreed to pay me to fangirl – er, write a blog – about Emerge, Return and the tour supporting it, so I’ll leave it there for the music criticism (their complete discography is now available on Bandcamp and Spotify). I’ll just add that a number of these ‘new’ songs have been kicking around for six to ten years but went unrecorded until now. For that reason, I worried that it might feel like a collection of cast-offs, but in fact they’ve managed to produce something sonically and thematically cohesive. It’s darker than some of their previous work, with moody minor chords and slightly sinister subjects.

I’ve often found that the band will zero in on a detail, scene, or idea that never would have stood out to me while reading a book but, in retrospect, evokes the whole with great success. I decided to test this out by reading Carol Birch’s Orphans of the Carnival in the weeks leading up to seeing them on their months-long UK summer/autumn tour. It’s a historical novel about real-life 1850s Mexican circus “freak” Julia Pastrana, who had congenital conditions that caused her face and body to be covered in thick hair and her jaw and lips to protrude. Cruel contemporaries called her the world’s ugliest woman and warned that pregnant women should not be allowed to see her on tour lest the shock cause them to miscarry. Medical doctors posited, in all seriousness, that she was a link between humans and orangutans.

My copy of Birch’s novel was a remainder, and it is certainly a minor work compared to the Booker Prize-shortlisted Jamrach’s Menagerie. Facts about Julia’s travel itinerary and fellow oddballs quickly grow tedious, and while one of course sympathizes when children throw rocks at her, she never becomes a fully realized character rather than a curiosity.

There is also a bizarre secondary storyline set in 1983, in which Rose fills her London apartment with hoarded objects, including a doll she rescues from a skip and names Tattoo. She becomes obsessed with the idea of visiting a doll museum in Mexico. I thought that Tattoo would turn out to be Julia’s childhood doll Yatzi (similar to in A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power, where dolls have sentimental and magical power across the centuries), but the connection, though literal, was not as I expected. It’s more grotesque than that. And stranger than fiction, frankly.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

Birch sticks to the known details of Julia’s life. She had various agents, the final one being Theo Lent, who married her. (In the novel, he can’t bring himself to kiss her, but he can, you know, impregnate her.) She died of a fever soon after childbirth. Her son, Theo Junior, who inherited her hypertrichosis, also died within days. Both bodies were embalmed, sold, and exhibited. Theo then married another hairy woman, Marie Bartel of Germany, who took the name “Zenora” and posed as Julia’s sister. Theo died, syphilitic (or so Birch implies) and insane, in a Russian asylum. Julia and Theo Junior’s remains were displayed and mislaid at various points over the years, with Julia’s finally repatriated to Mexico for a proper burial in 2013. In the novel, Tattoo is, in fact, Theo Junior’s mummy.

Birch sticks to the known details of Julia’s life. She had various agents, the final one being Theo Lent, who married her. (In the novel, he can’t bring himself to kiss her, but he can, you know, impregnate her.) She died of a fever soon after childbirth. Her son, Theo Junior, who inherited her hypertrichosis, also died within days. Both bodies were embalmed, sold, and exhibited. Theo then married another hairy woman, Marie Bartel of Germany, who took the name “Zenora” and posed as Julia’s sister. Theo died, syphilitic (or so Birch implies) and insane, in a Russian asylum. Julia and Theo Junior’s remains were displayed and mislaid at various points over the years, with Julia’s finally repatriated to Mexico for a proper burial in 2013. In the novel, Tattoo is, in fact, Theo Junior’s mummy.

Two Bookshop Band songs from the new album are about the novel: “Doll” and “Waggons and Wheels.” “Doll” is one of the few more lighthearted numbers on the album. It ended up being a surprise favourite track for me (along with the creepy “Eve in Your Garden,” about Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments, and “Room for Three,” a sombre yet resolute epic written for the launch of Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage) because of its jaunty music-hall tempo; the pattern of repeating most nouns three times; and the hand claps, “deedily” vocal fills, unhinged recorder playing, and springy sound effects. The lyrics are almost a riddle: “When’s a doll (doll doll) not a doll (doll doll)?” They somehow avoid all spoilers while conveying something of the mental instability of a couple of characters.

The gorgeous “Waggons and Wheels” picks up on the melancholy tone and parental worries of earlier tracks from the album. The chorus has a wistful air as Julia ponders the passage of time and her constant isolation: “old friends, new deals / Winter or spring, I am hiding … Winter or spring, I’ll be travelling.” Porter’s mellow soprano tempers Julia’s outrage at mistreatment: “who are you to shout / Indecency and shame? / Shocking, I shock, so lock me out / I’m locked into this face.” She fears, too, what will happen to her child, “a beast or a boy, a monster or joy”. Listening to the song, I feel that the band saw past the specifics to plumb the universal feelings that get readers empathizing with Julia as a protagonist. They’ve gotten to the essence of the story in a way that Birch perhaps never did. Mediocre book; lovely songs. (New (bargain) purchase – Dollar Tree, Bowie, Maryland) ![]()

I caught the Emerge, Return tour at St Nicolas’ Church in Abingdon (an event hosted by Mostly Books) last night. It was my sixth time seeing the Bookshop Band in concert – see also my write-ups of two 2016 events plus one in 2018 and another in 2019 – but the first time in person since the pandemic. I got to show off my limited-edition T-shirt. How nice it was to meet up again with blogger friend Annabel, too! Fun fact for you: Ben was born in Abingdon but hadn’t been back since he was two. Beth’s cousin turned up to the show as well. Although they have their daughters, 2 and 7, on the tour with them, they were being looked after elsewhere for the evening so the parents could relax a bit. Across the two sets, they played seven tracks from the new album, six old favourites, and two curios: one Spell Song, and an untitled song they wrote for the audiobook of Jackie Morris’s The Unwinding. It was a brilliant evening!

Dylan Thomas & Folio Prize Lists and a Book Launch

Literary prize season is upon us! I sometimes find it overwhelming, but mostly I love it. Last month I submitted a longlist of my top five manuscripts to be considered for the McKitterick Prize. In the past week the Dylan Thomas Prize longlist and Folio Prize shortlists have been announced. The press release for the former notes “an even split of debut and established names, with African diaspora and female voices dominating.”

- Limberlost by Robbie Arnott (Atlantic Books) – novel (Australia)

- Seven Steeples by Sara Baume (Tramp Press) – novel (Ireland)

- God’s Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu (Orion, Weidenfeld & Nicolson) – short story collection (Nigeria)

- Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer (Picador, Pan Macmillan) – novel (UK)

- Phantom Gang by Ciarán O’Rourke (The Irish Pages Press) – poetry collection (Ireland)

- Things They Lost by Okwiri Oduor (Oneworld) – novel (Kenya)

- Losing the Plot by Derek Owusu (Canongate Books) – novel (UK)

- I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel (Rough Trade Books) – novel (UK)

- Send Nudes by Saba Sams (Bloomsbury Publishing) – short story collection (UK)

- Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire (Chatto & Windus) – poetry collection (Somalia-UK)

- Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (Picador, Pan Macmillan) – novel (UK)

- No Land to Light On by Yara Zgheib (Atlantic Books, Allen & Unwin) – novel (Lebanon)

I happen to have already read Warsan Shire’s poetry collection and Nell Stevens’ debut novel (my review), which I loved and am delighted to see get more attention. I had Seven Steeples as an unsolicited review copy on my e-reader so have started reading that, and Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies is one of the books I treated myself to with Christmas money. There’s a possibility of a longlist blog tour, so for that I’ve requested the poetry book Phantom Gang. The shortlist will be announced on 23 March and the winner on 11 May.

This is the first year of the new Rathbones Folio Prize format: as in the defunct Costa Awards, the judges will choose a winner in each of three categories and then the category winners will go on to compete for an overall prize.

Nonfiction:

- The Passengers by Will Ashon

- In Love by Amy Bloom

- The Escape Artist by Jonathan Freedland

- Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

- The Social Distance Between Us by Darren McGarvey

Poetry:

- Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley

- Ephemeron by Fiona Benson

- Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa

- England’s Green by Zaffar Kunial

- Manorism by Yomi Ṣode

Fiction:

- Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo

- Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

- Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

- Emergency by Daisy Hildyard

- Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

Amy Bloom’s memoir In Love was one of my favourites last year, but I’m unfamiliar with the rest of the nonfiction shortlist and all the poetry collections are new to me (though I’ve read Zaffar Kunial’s Us). From the fiction list, I’m currently reading Elizabeth Strout’s Lucy by the Sea and I’ve read part of Sheila Heti’s bizarre Pure Colour and will try to get back into it on my Kindle at some point. In 2021 I was sent the entire Folio Prize shortlist to feature on my blog, but last year there was no contact from the publicists. I’ve expressed interest in receiving the poetry nominees, if nothing else.

The Women’s Prize longlist is always announced on International Women’s Day (8 March). Very unusually for me, I have already put together a list of novels we might see on that. I actually started compiling the list in 2022, and then last month spent some bookish procrastination time scouring the web for what I might have missed. There are 124 books on my list. Before cutting that down by 90% I have to decide if I want to be really thorough and check the publisher for each one (bar some exceptions, each publisher can only submit two books). I’ll work on that a bit more and post it in the next couple of weeks.

Last night I attended an online book launch (throwback to 2020!) via Sam Read Bookseller in Grasmere, for All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett. Vik saw me express interest in her book on Twitter and had her publisher, Two Roads, send me a copy. I knew I had to attend the launch event because the Bookshop Band wrote a song about the book and premiered it as a music video partway through the evening. I’ve read the first 50 pages so far and it’s a lovely book I’ll review in full later in the month.

The brief autobiographical essays, each titled after a wildflower and headed by a woodcut of it, sit somewhere between creative nonfiction and nature writing, with Bennett reflecting on her sister’s sudden accidental death, her years caring for elderly parents and an ill son, and the process of creating an “apothecary garden” from scratch on a social housing estate in Cumbria. Interviewed by Catherine Simpson (author of When I Had a Little Sister), she said that the book is about “what grows not in spite of brokenness, but because of it.” The format is such in part because it was written over the course of 10 years and Bennett could only steal moments at a time from full-time caregiving. She has also previously published poetry, but this is her prose debut.

The brief autobiographical essays, each titled after a wildflower and headed by a woodcut of it, sit somewhere between creative nonfiction and nature writing, with Bennett reflecting on her sister’s sudden accidental death, her years caring for elderly parents and an ill son, and the process of creating an “apothecary garden” from scratch on a social housing estate in Cumbria. Interviewed by Catherine Simpson (author of When I Had a Little Sister), she said that the book is about “what grows not in spite of brokenness, but because of it.” The format is such in part because it was written over the course of 10 years and Bennett could only steal moments at a time from full-time caregiving. She has also previously published poetry, but this is her prose debut.

Simpson asked if she found the writing of All My Wild Mothers cathartic and Bennett replied that she went to therapy for that purpose, but that time and words have indeed helped to mellow anger and self-pity. She found that she was close enough in time to the events she writes about to remember them, but not so close as to get lost in grief. The Bookshop Band’s song “Keeping the Magic,” mostly on cello and guitar, has imagery of wildflowers and trees and dwells on the maternal and muddling through. (You can watch a performance of it here.)

Yesterday was a day of bad family news for me, both a diagnosis and another sudden death, so this was a message I needed, of beauty and hope alongside the grief. It’s why I’m so earnestly seeking warmth and spring flowers this season. I found snowdrops in the park the other day, and crocuses in a neighbour’s garden today.

Which literary prize races will you follow this year?

What’s bringing joy into your life these days?

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.