20 Books of Summer, #18–19: The Other’s Gold and Black Dogs

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a novel about a quartet of college friends and the mistakes that mar their lives and a novella about the enduring impact of war set just after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

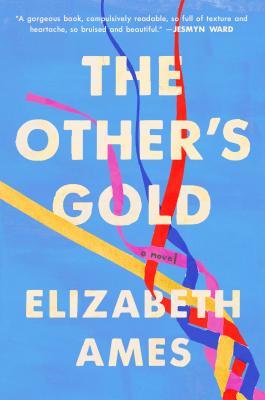

The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames (2019)

Make new friends but keep the old,

One is silver and the other’s gold.

Do you know that little tune? We would sing it as a round at summer camp. It provides a clever title for this story of four college roommates whose lives are marked by the threat of sexual violence and ambivalent feelings about motherhood. Alice, Ji Sun, Lainey and Margaret first meet as freshmen in 2002 when they’re assigned to the same suite (with a window seat! how envious am I?) at Quincy-Hawthorn College.

They live together for the whole four years – a highly unusual situation – and see each other through crises at college and in the years to come as they find partners and meander into motherhood. Iraq War protests and the Occupy movement form a turbulent background, but the friends’ overriding concerns are more personal. One girl was molested by her brother as a child and has kept secret her act of revenge; one has a crush on a professor until she learns he has sexual harassment charges being filed against him by multiple female students. Infertility later provokes jealousy between the young women, and mental health issues come to the fore.

They live together for the whole four years – a highly unusual situation – and see each other through crises at college and in the years to come as they find partners and meander into motherhood. Iraq War protests and the Occupy movement form a turbulent background, but the friends’ overriding concerns are more personal. One girl was molested by her brother as a child and has kept secret her act of revenge; one has a crush on a professor until she learns he has sexual harassment charges being filed against him by multiple female students. Infertility later provokes jealousy between the young women, and mental health issues come to the fore.

As in Expectation by Anna Hope, the book starts to be all about babies at a certain point. That’s not a problem if you’re prepared for and interested in this theme, but I love campus novels so much that my engagement waned as the characters left university behind. Also, the characters seemed too artificially manufactured to inject diversity (Ji Sun is a wealthy Korean; adopted Lainey is of mixed Latina heritage, and bisexual; Margaret has Native American blood) and embody certain experiences. And, unfortunately, any #MeToo-themed read encountered in the wake of My Dark Vanessa is going to pale by comparison.

Part One held my interest, but after that I skimmed to the end. Ideally, I would have chosen replacements and not included skims like this and Green Mansions, but it’s not the first summer that I’ve had to count DNFs and skimmed books – my time and attention are always being diverted by paid review work, review copies and library books with imminent deadlines. I’ve read lots of fiction about groups of female friends this summer, partly by accident and partly by design, and will likely do a feature on it in an upcoming month. For now, I’d recommend Lara Feigel’s The Group instead of this.

With thanks to Pushkin Press (ONE imprint) for the free e-copy for review.

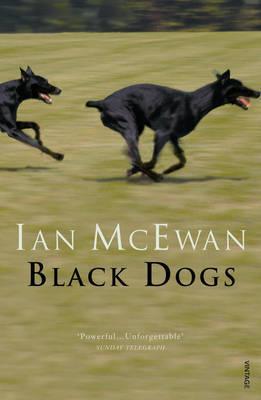

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan (1992)

When I read the blurb, I worried I’d read this before and forgotten it: all it mentions is a young couple setting off on honeymoon and having an encounter with evil. Isn’t that the plot of The Comfort of Strangers? I thought. In fact, this only happens to have the vacation detail in common, and has a very different setup and theme overall.

When I read the blurb, I worried I’d read this before and forgotten it: all it mentions is a young couple setting off on honeymoon and having an encounter with evil. Isn’t that the plot of The Comfort of Strangers? I thought. In fact, this only happens to have the vacation detail in common, and has a very different setup and theme overall.

Jeremy lost his parents in a car accident (my least favourite fictional trope – far too convenient a way of setting a character off on their own!) when he was eight years old, and is self-aware enough to realize that he has been seeking for parental figures ever after. He becomes deeply immersed in the story of his wife’s parents, Bernard and June, even embarking on writing a memoir based on what June, from her nursing home bed, tells him of their early life (Part One).

After June’s death, Jeremy takes Bernard to Berlin (Part Two) to soak up the atmosphere just after the Wall comes down, but the elderly man is kicked by a skinhead. The other key thing that happens on this trip is that he refutes June’s account of their honeymoon. At June’s old house in France (Part Three), Jeremy feels her presence and seems to hear the couple’s voices. Only in Part Four do we learn what happened on their 1946 honeymoon trip to France: an encounter with literal black dogs that also has a metaphorical dimension, bringing back the horrors of World War II.

I think the novel is also meant to contrast Communist ideals – Bernard and June were members of the Party in their youth – with how Communism has played out in history. It was shortlisted for the Booker, which made me feel that I must be missing something. A fairly interesting read, most similar in his oeuvre (at least of the 15 I’ve read so far) to The Child in Time. (Secondhand purchase from a now-defunct Newbury charity shop)

Coming up next: The latest book by John Green – it’s due back at the library on the 31st so I’ll aim to review it before then, possibly with a rainbow-covered novel as a bonus read.

Three May Graphic Novel Releases: Orwell, In, and Coma

These three terrific graphic novels all have one-word titles and were published on the 13th of May. Outwardly, they are very different: a biography of a famous English writer, the story of an artist looking for authentic connections, and a memoir of a medical crisis that had permanent consequences. The drawing styles are varied as well. But if the books share one thing, it’s an engagement with loneliness: It’s tempting to see the self as being pitted against the world, with illness an additional isolating force, but family, friends and compatriots are there to help us feel less alone and like we are a part of something constructive.

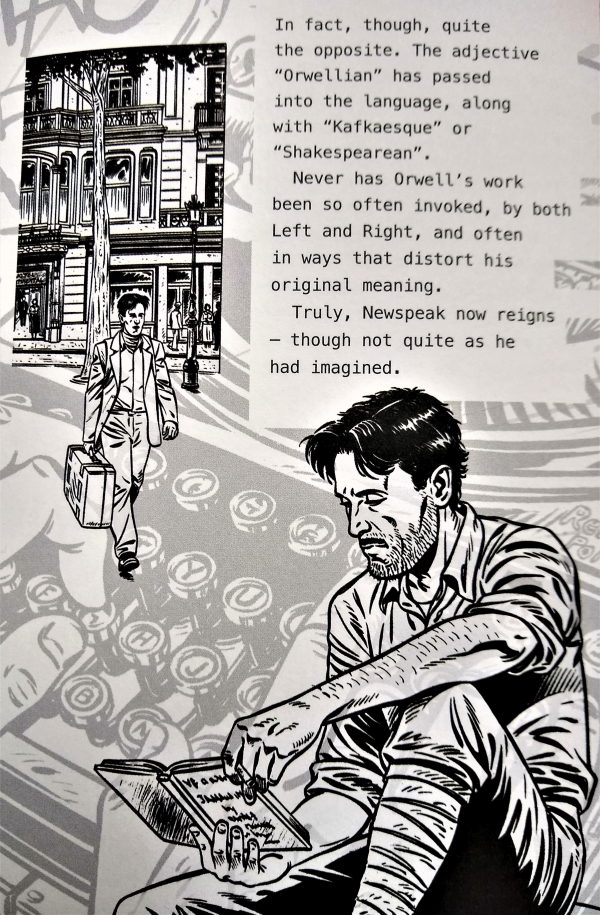

Orwell by Pierre Christin; illustrated by Sébastien Verdier

[Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin]

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

The book’s settings range from Spain, where Orwell went to fight in the Civil War, via a bomb shelter in London’s Underground, to the island of Jura, where he retired after the war. I particularly loved the Scottish scenery. I also appreciated the notes on where his life story entered into his fiction (especially in A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying). During World War II he joined the Home Guard and contributed to BBC broadcasting alongside T.S. Eliot. He had married Eileen, adopted a baby boy, and set up a smallholding. Even when hospitalized for tuberculosis, he wouldn’t stop typing (or smoking).

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

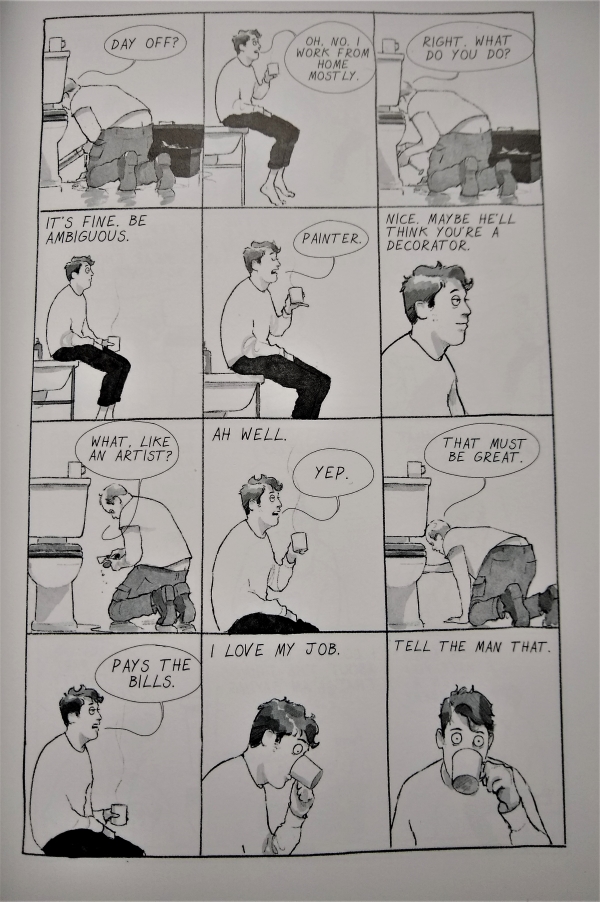

In by Will McPhail

Nick never knows the right thing to say. The bachelor artist’s well-intentioned thoughts remain unvoiced, such that all he can manage is small talk. Whether he’s on a subway train, interacting with his mom and sister, or sitting in a bar with a tongue-in-cheek name (like “Your Friends Have Kids” or “Gentrificchiato”), he’s conscious of being the clichéd guy who’s too clueless or pathetic to make a real connection with another human being. That starts to change when he meets Wren, a Black doctor who instantly sees past all his pretence.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Alternately laugh-out-loud funny and tender, McPhail’s debut novel is as hip as it is genuine. It’s a spot-on picture of modern life in a generic city. I especially loved the few pages when Nick is on a Zoom call with carefully ironed shirt but no trousers and the potential employers on the other end get so lost in their own jargon that they forget he’s there. His banter with Wren or with his sister reveals a lot about these characters, but there’s also an amazing 12-page wordless sequence late on that conveys so much. While I’d recommend this to readers of Alison Bechdel, Craig Thompson, and Chris Ware (and expect it to have a lot in common with Kristen Radtke’s forthcoming Seek You: A Journey through American Loneliness), it’s perfect for those brand new to graphic novels, too – a good old-fashioned story, with all the emotional range of Writers & Lovers. I hope it’ll be a wildcard entry on the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Coma by Zara Slattery

In May 2013, Zara Slattery’s life changed forever. What started as a nagging sore throat developed into a potentially deadly infection called necrotising fascitis. She spent 15 days in a medically induced coma and woke up to find that one of her legs had been amputated. As in Orwell and In, colour is used to differentiate different realms. Monochrome sketches in thick crayon illustrate her husband Dan’s diary of the everyday life that kept going while she was in hospital, yet it’s the coma/fantasy pages in vibrant blues, reds and gold that feel more real.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Meanwhile, Dan was holding down the fort, completing domestic tasks and reassuring their three children. Relatives came to stay; neighbours brought food, ran errands, and gave him lifts to the hospital. He addresses the diary directly to Zara as a record of the time she spent away from home and acknowledges that he doesn’t know if she’ll come back to them. A final letter from Zara’s nurse reveals how bad off she was, maybe more so than Dan was aware.

This must have been such a distressing time to revisit. In this interview, Slattery talks about the courage it took to read Dan’s diary even years after the fact. I admired how the book’s contrasting drawing styles recreate her locked-in mental state and her family’s weeks of waiting – both parties in limbo, wondering what will come next.

Brighton, where Slattery is based, is a hotspot of the Graphic Medicine movement spearheaded by Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor). Regular readers know how much I love health narratives, and with my keenness for graphic novels this series couldn’t be better suited to my interests.

With thanks to Myriad Editions for the free copy for review.

Read any graphic novels recently?

We Are the Weather by Jonathan Safran Foer

I’ve read all of Jonathan Safran Foer’s major releases, from Everything Is Illuminated onwards, and his 2009 work Eating Animals had a major impact on me. (I included it on a 2017 list of “Books that (Should Have) Literally Changed My Life.”) It’s an exposé of factory farming that concludes meat-eating is unconscionable, and while I haven’t gone all the way back to vegetarianism in the years since I read it, I eat meat extremely rarely, usually only when a guest at others’ houses, and my husband and I often eat vegan meals at home.

When I heard that Foer’s new book, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast, would revisit the ethics of eating meat, I worried it might feel redundant, but still wanted to give it a try. Here he examines the issue through the lens of climate change, arguing that slashing meat consumption by two-thirds or more (by eating vegan until dinner, i.e., for two meals a day) is the easiest way for individuals to decrease their carbon footprint. I don’t disagree with this proposal. It would be churlish to fault a reasonable suggestion that gives ordinary folk something concrete to do while waiting (in vain?) for governments to act.

When I heard that Foer’s new book, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast, would revisit the ethics of eating meat, I worried it might feel redundant, but still wanted to give it a try. Here he examines the issue through the lens of climate change, arguing that slashing meat consumption by two-thirds or more (by eating vegan until dinner, i.e., for two meals a day) is the easiest way for individuals to decrease their carbon footprint. I don’t disagree with this proposal. It would be churlish to fault a reasonable suggestion that gives ordinary folk something concrete to do while waiting (in vain?) for governments to act.

My issues, then, are not with the book’s message but with its methods and structure. Initially, Foer successfully makes use of historical parallels like World War II and the civil rights movement. He rightly observes that we are at a crucial turning point and it will take self-denial and joining in with a radical social movement to protect a whole way of life. Don’t think of living a greener lifestyle as a sacrifice or a superhuman feat, Foer advises; think of it as an opportunity for bravery and for living out the convictions you confess to hold.

As the book goes on, however, the same reference points come up again and again. It’s an attempt to build on what’s already been discussed, but just ends up sounding repetitive. Meanwhile, the central topic is brought in as a Trojan horse: not until page 64 (of 224 in the main text) does Foer lay his cards on the table and admit “This is a book about the impacts of animal agriculture on the environment.” Why be so coy when the book has been marketed as being about food choices? The subtitle and blurb make the topic clear. “Our planet is a farm,” Foer declares, with animal agriculture the top source of deforestation and methane emissions.

Fair enough, but as I heard a UK climate expert explain the other week at a local green fair, you can’t boil down our response to the climate crisis to ONE strategy. Every adjustment has to work in tandem. So while Foer has chosen meat-eating as the most practical thing to change right now, the other main sources of emissions barely get a mention. He admits that car use, number of children, and flights are additional areas where personal choices make a difference, but makes no attempt to influence attitudes in these areas. So diet is up for discussion, but not family planning, commuting or vacations? This struck me as a lack of imagination, or of courage. Separating Americans from their vehicles may be even tougher than getting them to put down the burgers. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying.

Part II is a bullet-pointed set of facts and statistics reminiscent of the “Tell the Truth” section in the Extinction Rebellion handbook. It’s an effective strategy for setting things out briefly, yet sits oddly between narrative sections of analogies and anecdotes. My favorite bits of the book were about visits to his dying grandmother back at the family home in Washington, D.C. It took him many years to realize that his grandfather, who lost everything in Poland and began again with a new wife in America, committed suicide. This family history,* nestled within the canon of Jewish stories like Noah’s Ark, Masada and the Holocaust, dramatizes the conflict between resistance and self-destruction – the very battle we face now.

Part II is a bullet-pointed set of facts and statistics reminiscent of the “Tell the Truth” section in the Extinction Rebellion handbook. It’s an effective strategy for setting things out briefly, yet sits oddly between narrative sections of analogies and anecdotes. My favorite bits of the book were about visits to his dying grandmother back at the family home in Washington, D.C. It took him many years to realize that his grandfather, who lost everything in Poland and began again with a new wife in America, committed suicide. This family history,* nestled within the canon of Jewish stories like Noah’s Ark, Masada and the Holocaust, dramatizes the conflict between resistance and self-destruction – the very battle we face now.

Part IV, Foer’s “Dispute with the Soul,” is a philosophical dialogue in the tradition of Talmudic study, while the book closes with a letter to his sons. Individually, many of these segments are powerful in the way they confront hypocrisy and hopelessness with honesty. But together in the same book they feel like a jumble. Although it was noble of Foer to tackle the subject of climate change, I’m not convinced he was the right person to write this book, especially when we’ve already had recent works like The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells. Arriving at a rating has been very difficult for me because I support the book’s aims but often found it a frustrating reading experience. Still, if it wakes up even a handful of readers to the emergency we face, it will have been worthwhile.

Part IV, Foer’s “Dispute with the Soul,” is a philosophical dialogue in the tradition of Talmudic study, while the book closes with a letter to his sons. Individually, many of these segments are powerful in the way they confront hypocrisy and hopelessness with honesty. But together in the same book they feel like a jumble. Although it was noble of Foer to tackle the subject of climate change, I’m not convinced he was the right person to write this book, especially when we’ve already had recent works like The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells. Arriving at a rating has been very difficult for me because I support the book’s aims but often found it a frustrating reading experience. Still, if it wakes up even a handful of readers to the emergency we face, it will have been worthwhile.

My rating:

A favorite passage: “Climate change is not a jigsaw puzzle on the coffee table, which can be returned to when the schedule allows and the feeling inspires. It is a house on fire.”

*I’m looking forward to his mother Esther Safran Foer’s family memoir, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here: A Post-Holocaust Memoir, which is coming out from Tim Duggan Books on March 31, 2020.

*I’m looking forward to his mother Esther Safran Foer’s family memoir, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here: A Post-Holocaust Memoir, which is coming out from Tim Duggan Books on March 31, 2020.

We Are the Weather is published today, 10th October, in the UK by Hamish Hamilton (my thanks for the proof copy for review). It came out in the States from Farrar, Straus and Giroux last month.

Doorstopper of the Month: The Flight Portfolio by Julie Orringer

Julie Orringer’s The Invisible Bridge was the highlight of my 20 Books of Summer last year. I was thus delighted to hear that her second novel, The Flight Portfolio, nearly a decade in the making, was coming out this year, and even more thrilled to receive the review copy I requested while staying at my mother’s in America.

The Invisible Bridge was the saga of a Hungarian Jewish family’s experiences in the Second World War; while The Flight Portfolio again charts the rise of Nazism and a growing awareness of Jewish extermination, it’s a very different though equally affecting narrative. Its protagonist is a historical figure, Varian Fry, a Harvard-educated journalist who founded the Emergency Rescue Committee to help at-risk artists and writers escape to the United States from France, and many of the supporting characters are also drawn from real life.

The Invisible Bridge was the saga of a Hungarian Jewish family’s experiences in the Second World War; while The Flight Portfolio again charts the rise of Nazism and a growing awareness of Jewish extermination, it’s a very different though equally affecting narrative. Its protagonist is a historical figure, Varian Fry, a Harvard-educated journalist who founded the Emergency Rescue Committee to help at-risk artists and writers escape to the United States from France, and many of the supporting characters are also drawn from real life.

In 1940, when Varian is 32, he travels to Marseille to coordinate the ERC’s operations on the ground. Every day his office interviews 60 refugees and chooses 10 to recommend to the command center in New York City. Varian and his staff arrange bribes, fake passports, and exit visas to get Jewish artists out of the country via the Pyrenees or various sea routes. Their famous clients include Hannah Arendt, André Breton, Marc Chagall, André Gide and members of Thomas Mann’s family, all of whom make cameo appearances.

Police raids and deportation are constant threats, but there is still joy – and absurdity – to be found in daily life, especially thanks to Breton and the other Surrealists who soon share Varian’s new headquarters at Villa Air-Bel (which you can tour virtually here). They host dinner parties – one in the nude – based around games and spectacles, even when wartime food shortages mean there’s little besides foraged snails or the goldfish from the pond to eat.Like The Invisible Bridge, The Flight Portfolio is a love story, if not in the way you might expect. Soon after he arrives in Marseille, Varian is contacted by a Harvard friend – and ex-lover – he hasn’t heard from in 12 years, Elliott Grant. Grant begs Varian to help him find his Columbia University teaching colleague’s son and get him out of Europe. Even though Varian doesn’t understand why Grant is so invested in Tobias Katznelson, he absorbs the sense of urgency. As Varian and Grant renew their clandestine affair, Tobias’s case becomes a kind of microcosm of the ERC’s work. Amid layers of deception, it stands as a symbol of the value of one human life. Varian gradually comes to accept that he can’t save everyone, but maybe if he can save Tobias he’ll win Grant back.

Nearly eighty years on, this plot strand still feels perfectly timely. Varian is married to Eileen and has been passing for straight, yet he doesn’t fit the stereotype of a homosexual hiding behind marriage to a woman. In fact, the novel makes it plain that Varian was bisexual; he truly loved Eileen, but Grant was the love of his life. Can he face the truth and find courage to live as he truly is? The same goes for Grant, who has an additional secret. Orringer’s Author’s Note, at the end of the book, explains how much of this is historical and how much is made up, and what happened next for Varian. I’ll let you discover it for yourself.

The Flight Portfolio didn’t sweep me away quite as fully as The Invisible Bridge did, perhaps because the litany of refugee cases and setbacks over the course of the novel’s one-year chronology verges on overwhelming. I also had only a vague impression of most of Varian’s colleagues, and there are a few too many Mantel-esque “he, Varian”-type constructions to clarify which male character is acting.On the whole, though, this is historical fiction at its best. It conveys how places smell and sound with such rich detail. The sorts of descriptive passages one skims over in other books are so gorgeous and evocative here that they warrant reading two or even three times. The story of an accidental hero torn between impossible choices is utterly compelling. I’m convinced, if I wasn’t already, that Julie Orringer is among our finest living writers, and this is my top novel of 2019 so far.

Two favorite passages:

“If we could pin down the moments when our lives bifurcate into before and after—if we could pause the progression of millisecond, catch ourselves at the point before we slip over the precipice—if we could choose to remain suspended in time-amber, our lives intact, our hearts unbroken, our foreheads unlined, our nights full of undisturbed sleep—would we slip, or would we choose the amber?”

“Evening was falling, descending along the Val d’Huveaune like a shadow cloak, like a tissue-thin eyelid hazed with veins. Varian stood at the open window, dressing for dinner; Grant, at the harpsichord downstairs, conjured a Handel suite for the arriving guests. … From outside came the scent of sage and wet earth; a rainstorm had tamped down the afternoon’s dust, and the mistral blew across the valley. A nightingale lit in the medlar tree beneath the window and launched into variegated song. It occurred to Varian that the combination of voices below … made a music soon to be lost forever.”

Page count: 562

My rating:

With thanks to Knopf for the free copy for review.

Next month: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

#16–17: The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt & The Invisible Bridge

I’m coming towards the close of my 20 Books of Summer challenge. Now, I’ve done plenty of substituting – some of my choices from early in the summer will have to spill over into the autumn (for instance, I’m reading the May Sarton biography slowly and carefully so am unlikely to finish it before early September) or simply wait for another time – but in the end I will have read 20+ books I own in print by women authors. (Ongoing/still to come are a few buddy reads: Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie with Anna Caig; Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay with Naomi of Consumed by Ink and Penny of Literary Hoarders; and West with the Night by Beryl Markham with Laila of Big Reading Life.)

The two #20Booksof Summer I finished most recently have been the best so far. I’d heard great things about these debut novels but let years go by before getting hold of them, and then months more before picking them up. Though one is more than twice the length of the other, they are both examples of large-scale storytelling at its best: we as readers are privy to the sweep of a whole life, and get to know the protagonists so well that we ache for their sorrow. What might have helped the authors tap into the emotional power of their stories is that both drew on family history, to different extents, when creating the characters and incidents.

The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr (2013)

Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. When we meet our 81-year-old narrator, she’s just performed at the 1991 Transformer Festival and has caught the attention of a younger acolyte who wants to come interview her at home near Perth, Australia for a documentary film – a setup that reminded me a bit of May Sarton’s Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing. It’s pretty jolting the first time we see Lena smoke, but as her life story unfolds it becomes clear that it’s been full of major losses, some nearly unbearable in their cruelty, so it’s no surprise that she would wish to forget.

Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. When we meet our 81-year-old narrator, she’s just performed at the 1991 Transformer Festival and has caught the attention of a younger acolyte who wants to come interview her at home near Perth, Australia for a documentary film – a setup that reminded me a bit of May Sarton’s Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing. It’s pretty jolting the first time we see Lena smoke, but as her life story unfolds it becomes clear that it’s been full of major losses, some nearly unbearable in their cruelty, so it’s no surprise that she would wish to forget.

Though Lena bridles at Mo’s many probing questions, she realizes this may be her last chance to have her say and starts typing up a record of her later years to add to a sheaf of autobiographical stories she wrote earlier in life. These are interspersed with the present action to create a vivid collage of Lena’s life: growing up with a pet monkey in Singapore, moving to New Zealand with her lover, frequenting jazz clubs in Paris, and splitting her time between teaching music in England and performing in New York City.

With perfect pitch and recall, young Lena moved easily from the piano to the cello to the theremin. I loved how Farr evokes the strangeness and energy of theremin music, and how sound waves find a metaphorical echo in the ocean’s waves – swimming is Lena’s other great passion. Life has been an overwhelming force from which she’s only wrested fleeting happiness, and there’s a quiet, melancholic dignity to her voice. This was nominated for several prizes in Australia, where Farr is from, but has been unfairly overlooked elsewhere.

Favorite lines:

“I once again wring magic from the wires by simply plucking and stroking my fingers in the aether.”

“I felt the rush of the electrical field through my body. I felt like a god. I felt like a queen. I felt like a conqueror. And I wanted to play it forever.”

“All of the stories of my life have begun and ended with the ocean.”

My rating:

The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt was published in the UK by Aardvark Bureau in 2016. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2010)

It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read. It bears similarities to other war sagas such as Birdsong and All the Light We Cannot See, but the focus on the Hungarian Jewish experience was new for me. Although there are brief glimpses backwards and forwards, most of the 750-page book is set during the years 1937–45, as Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe.

It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read. It bears similarities to other war sagas such as Birdsong and All the Light We Cannot See, but the focus on the Hungarian Jewish experience was new for me. Although there are brief glimpses backwards and forwards, most of the 750-page book is set during the years 1937–45, as Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe.

A story of survival against all the odds, this doesn’t get especially dark until the last sixth or so, and doesn’t stay really dark for long. So if you think you can’t handle another Holocaust story, I’d encourage you to make an exception for Orringer’s impeccably researched and plotted novel. Even in labor camps, there are flashes of levity, like the satirical newspapers that Andras and a friend distribute among their fellow conscripts, while the knowledge that the family line continues into the present day provides a hopeful ending.

This is a flawless blend of family legend, wider history, and a good old-fashioned love story. I read the first 70 pages on the plane back from America but would have liked to find more excuses to read great big chunks of it at once. Sinking deep into an armchair with a doorstopper is a perfect summer activity (though also winter … any time, really). [First recommended to me by Andrea Borod (aka the Book Dumpling) over five years ago.]

Favorite lines:

“He felt the stirring of a new ache, something like homesickness but located deeper in his mind; it was an ache for the time when his heart had been a simple and satisfied thing, small as the green apples that grew in his father’s orchard.”

“[It] seemed to be one of the central truths of his life: that in any moment of happiness there was a reminder of bitterness or tragedy, like the ten plague drops spilled from the Passover cup, or the taste of wormwood in absinthe that no amount of sugar could disguise.”

“For years now, he understood at last, he’d had to cultivate the habit of blind hope. It had become as natural to him as breathing.”

My rating:

This year I’ve been joining in Liz’s

This year I’ve been joining in Liz’s

Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes.

Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes.

My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog.

My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog. Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent.

Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent. This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to

This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to  Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection. Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

I started another April 5th release on my Kindle a couple of weeks ago, Things Bright and Beautiful by Anbara Salam. It’s about a missionary couple whose lives are disrupted by the return of an older missionary. I was thinking of abandoning it until I got to the last line of the prologue, which threw in a pretty great twist. So maybe I’ll go back to it.

I started another April 5th release on my Kindle a couple of weeks ago, Things Bright and Beautiful by Anbara Salam. It’s about a missionary couple whose lives are disrupted by the return of an older missionary. I was thinking of abandoning it until I got to the last line of the prologue, which threw in a pretty great twist. So maybe I’ll go back to it. If you loved The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, I have just the book for you: another feel-good World War II-set novel with characters you’ll cheer for. December 1940, London: Twenty-two-year-old Emmeline Lake dreams of being a Lady War Correspondent, but for now she’ll start by typing up the letters submitted to Henrietta Bird’s advice column in Woman’s Friend. All too quickly, though, the job feels too small for Emmy. Mrs. Bird refuses to print letters on Unpleasant subjects, which could include anything from an inappropriate crush to anxiety. She thinks cowardly readers bring their troubles on themselves and need to buck up instead of looking to others for help. But Emmy can’t bear to throw hurting people’s missives away. Perhaps she could send some advice of her own?

If you loved The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, I have just the book for you: another feel-good World War II-set novel with characters you’ll cheer for. December 1940, London: Twenty-two-year-old Emmeline Lake dreams of being a Lady War Correspondent, but for now she’ll start by typing up the letters submitted to Henrietta Bird’s advice column in Woman’s Friend. All too quickly, though, the job feels too small for Emmy. Mrs. Bird refuses to print letters on Unpleasant subjects, which could include anything from an inappropriate crush to anxiety. She thinks cowardly readers bring their troubles on themselves and need to buck up instead of looking to others for help. But Emmy can’t bear to throw hurting people’s missives away. Perhaps she could send some advice of her own?

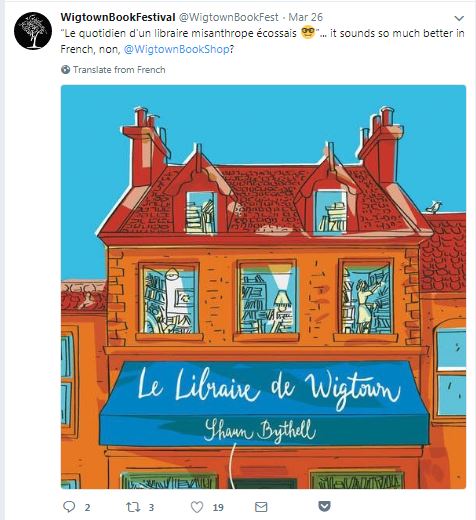

On Monday we’re off to Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town, for five days. Though we’ve been to Hay-on-Wye, Wales six times, we’ve never been to Wigtown despite meaning to for years. When I read Shaun Bythell’s Wigtown bookselling memoir last autumn, it felt like a sign that it was time. Did you see his

On Monday we’re off to Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town, for five days. Though we’ve been to Hay-on-Wye, Wales six times, we’ve never been to Wigtown despite meaning to for years. When I read Shaun Bythell’s Wigtown bookselling memoir last autumn, it felt like a sign that it was time. Did you see his

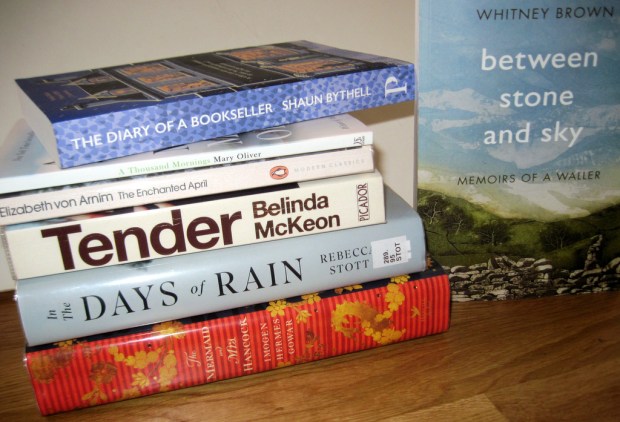

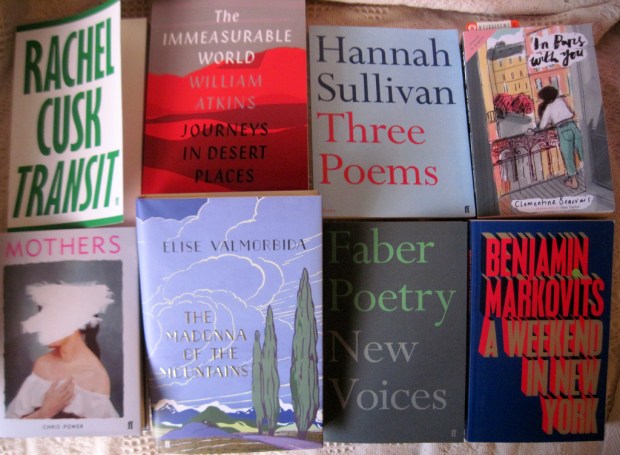

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.