The 2024 McKitterick Prize Shortlist and Winner

For the third year in a row, I was a first-round judge for the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel, published or unpublished, by a writer over 40), helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts. The McKitterick Prize is in memory of Tom McKitterick and sponsored by the Hawthornden Foundation. Thus far an unpublished manuscript has not advanced to the shortlist, but maybe one year it will!

On the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist (synopses adapted from Goodreads):

Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Jonathan Cape, Vintage, Penguin Random House) – “Set amid the Jamaican diaspora in London at the dawn of 1980s, a mesmerizing story of love, loss, and self-discovery that vibrates with the liberating power of music. When Yamaye meets Moose, a soulful carpenter who shares her Jamaican heritage, a path toward a different kind of future seems to open. But then, Babylon rushes in.”

Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Jonathan Cape, Vintage, Penguin Random House) – “Set amid the Jamaican diaspora in London at the dawn of 1980s, a mesmerizing story of love, loss, and self-discovery that vibrates with the liberating power of music. When Yamaye meets Moose, a soulful carpenter who shares her Jamaican heritage, a path toward a different kind of future seems to open. But then, Babylon rushes in.”

Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here (Pan Macmillan, Picador) – “We begin at the end. The armies of the National Defence Movement have been crushed and our unnamed narrator and his unit are surrounded. As he recounts the events leading to his disastrous finale, we learn how this gentle man is gradually transformed into a war criminal, committing acts he wouldn’t have thought himself capable.”

Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here (Pan Macmillan, Picador) – “We begin at the end. The armies of the National Defence Movement have been crushed and our unnamed narrator and his unit are surrounded. As he recounts the events leading to his disastrous finale, we learn how this gentle man is gradually transformed into a war criminal, committing acts he wouldn’t have thought himself capable.”

Aoife Fitzpatrick for The Red Bird Sings (Virago) – “West Virginia, 1897. When young Zona Heaster Shue dies only a few months after her wedding, her mother, Mary Jane, becomes convinced Zona was murdered by her husband, Trout, the town blacksmith. As the trial rises to fever pitch, with the men of Greenbrier County aligned against them, Mary Jane and Zona’s best friend Lucy must decide whether to reveal Zona’s greatest secret in the service of justice.”

Aoife Fitzpatrick for The Red Bird Sings (Virago) – “West Virginia, 1897. When young Zona Heaster Shue dies only a few months after her wedding, her mother, Mary Jane, becomes convinced Zona was murdered by her husband, Trout, the town blacksmith. As the trial rises to fever pitch, with the men of Greenbrier County aligned against them, Mary Jane and Zona’s best friend Lucy must decide whether to reveal Zona’s greatest secret in the service of justice.”

Greg Jackson for The Dimensions of a Cave (Granta) – “When investigative reporter Quentin Jones’s story about covert military interrogation practices in the Desert War is buried, he is spurred to dig deeper, and he unravels a trail that leads to VIRTUE: cutting-edge technology that simulates reality during interrogation. As the shadowy labyrinths of governmental corruption unfurl and tighten around him, unnerving links to his protégé – who, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, disappeared in the war several years earlier – keep emerging.”

Greg Jackson for The Dimensions of a Cave (Granta) – “When investigative reporter Quentin Jones’s story about covert military interrogation practices in the Desert War is buried, he is spurred to dig deeper, and he unravels a trail that leads to VIRTUE: cutting-edge technology that simulates reality during interrogation. As the shadowy labyrinths of governmental corruption unfurl and tighten around him, unnerving links to his protégé – who, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, disappeared in the war several years earlier – keep emerging.”

Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer (Atlantic Books, Allen & Unwin) – “The Funeral Cryer long ago accepted the mundane realities of her life: avoided by fellow villagers because of the stigma attached to her job and under-appreciated by her husband, whose fecklessness has pushed the couple close to the brink of break-up. But just when things couldn’t be bleaker, she takes a leap of faith – and in so doing things start to take a surprising turn for the better.”

Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer (Atlantic Books, Allen & Unwin) – “The Funeral Cryer long ago accepted the mundane realities of her life: avoided by fellow villagers because of the stigma attached to her job and under-appreciated by her husband, whose fecklessness has pushed the couple close to the brink of break-up. But just when things couldn’t be bleaker, she takes a leap of faith – and in so doing things start to take a surprising turn for the better.”

Allan Radcliffe for The Old Haunts (Fairlight Books) – “Recently bereaved Jamie is staying at a rural steading in the heart of Scotland with his actor boyfriend Alex. The sudden loss of both of Jamie’s parents hangs like a shadow over the trip. In his grief, Jamie finds himself sifting through bittersweet memories, from his working-class upbringing in Edinburgh to his bohemian twenties in London, with a growing awareness of his sexuality threaded through.”

Allan Radcliffe for The Old Haunts (Fairlight Books) – “Recently bereaved Jamie is staying at a rural steading in the heart of Scotland with his actor boyfriend Alex. The sudden loss of both of Jamie’s parents hangs like a shadow over the trip. In his grief, Jamie finds himself sifting through bittersweet memories, from his working-class upbringing in Edinburgh to his bohemian twenties in London, with a growing awareness of his sexuality threaded through.”

The Society of Authors kindly sent me free copies of the six shortlisted novels. I already had The Red Bird Sings and The Funeral Cryer on my TBR, so I’m particularly looking forward to reading them as part of my 20 Books of Summer – which I’ve decided might as well contain, as well as all hardbacks, only books by women.

I was familiar with Fire Rush from its shortlisting for last year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. The other three titles are new to me but sound interesting, especially The Old Haunts – at 150 pages, it will be perfect for Novellas in November.

My fellow judge Rónán Hession, whom I got to meet very briefly on a Zoom call, wrote: “It is exciting to judge a prize and encounter such a depth of talent. Though [the books] hugely varied in subject matter and style, the writers on the shortlist all impressed me with the clarity of their creative vision and their narrative authority on the page.”

The winner and runner-up were announced in advance of the SoA Awards ceremony in London yesterday evening. As in other years, I watched the livestream, which this year included captivating speeches by the Very Revd Dr Mark Oakley, Dean of Southwark Cathedral (where the ceremony took place) and Kate Mosse. And what a thrill it was to see and hear my name on the livestream!

Winner: Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer

Runner-up: Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here

In the press release announcing the winners, Hession said, “Wenyan Lu has created an unforgettable debut, brimming with personality and written with a sense of consummate ease. The Funeral Cryer is such a funny, warm and original book. An absolute gem of a novel.” I can’t wait to get started!

Other notable winners announced yesterday included:

- Tom Crewe for The New Life (Betty Trask Prize for a first novel by a writer under 35)

- Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Paul Torday Memorial Prize for a first novel by a writer over 60 – how perfect for her to win this in place of the McKitterick!)

- Soula Emmanuel for Wild Geese (Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on travel)

- Cecile Pin for Wandering Souls (Runner-up for the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize; and a Somerset Maugham Award travel bursary)

Carol Shields Prize Longlist: A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power

my doll is a collector of tragedy … the device I use to hide from something I already know

Mona Susan Power’s fourth novel, A Council of Dolls, is an Indigenous saga that draws on her own family history. Through first-person narratives by three generations of Dakhóta and Lakhóta women, she explores the ongoing effects of trauma resulting from colonialist oppression. The journey into the past begins with Sissy, a little girl in racist 1960s Chicago with an angry, physically abusive mother, Lillian. This section sets up the book’s pattern of ascribing voice and agency to characters’ dolls. Specifically, Sissy dissociates from her own emotions and upsetting experiences by putting them onto Ethel, her Black doll. Power relies on the dramatic irony between Sissy’s childhood perspective and readers’ understanding.

Moving backward: In 1930s North Dakota, we see Lillian coping with her father’s alcohol-fuelled violence by pretending she is being directed in a play. She loses her Shirley Temple doll, Mae, in an act of charity towards a sickly girl in the community. Lillian and her sister, Blanche, attend an Indian school in Bismarck. Run by nuns, it’s even crueller than the institution their parents, Cora and Jack, attended: the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (also a setting in Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange). Cora’s beautifully introspective journal from the 1910s reveals the systematic cultural annihilation that took place there. Her doll, Winona, rescued from a massacre in the time of Sitting Bull, was on the pyre of precious belongings – tribal costumes, instruments, medals, sacred feathers – burned on students’ arrival. But her stone heart survives as a totem of resilience.

This is a powerful but harrowing story. The characterization and narration are strong, and the nesting-dolls structure means we get glimpses into the future for all three protagonists. However, I was disappointed by a number of Power’s decisions. It appeared that a fourth and final narrator close to the present day would introduce another aspect, but in fact Jesse is a new name that Sissy chose for herself. Now a 50-year-old academic and writer, she becomes a medium for the dolls’ accounts – but this ends up repeating material we’d already encountered. The personification of familial tragedy in the figure of “the injured woman” who appears to Cora verges on mawkish, and the touches of magic realism to do with the dolls sit uneasily beside clinical discussions of trauma. In Jesse’s section, there is something unsubtle about how this forms the basis of a conversation between her and her friend Izzy:

(Jesse thinks) “I wanted that chance to break the chain of passing on harmful inner scripts, the self-loathing that comes from brutally effective colonization.”

(Izzy says) “whoo, that’s a big fat pipe full of misery … Our people have been pathologized from the very beginning. Still are.”

It’s possible I would have responded to this with more enthusiasm had it been packaged as a family memoir. As it is, I was unsure about the hybridization of autofiction and magic realism and wondered what white readers coming to the novel should conclude. I kept in mind Elaine Castillo’s essay “How to Read Now,” about her sense of BIPOC writers’ job: “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. Perhaps Power’s novel was not primarily intended to serve in that way.

I’ll let her have the last word, via the Author’s Note: “outrageously prejudiced depictions of my ancestors and our people are one reason I became a writer. From childhood I felt an urgent need to speak my truth, which was long suppressed. Writing this book was a healing endeavor. May it support the healing of others.”

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Mariner Books for the free e-copy for review.

This was a buddy read with Laura; see her review here.

Before the shortlist is announced on 9 April, I plan to review my two current reads, Cocktail by Lisa Alward and Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang, and concoct a personal wish list.

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

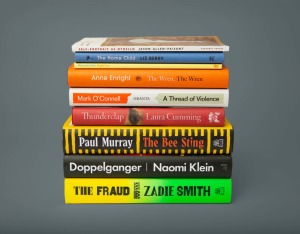

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

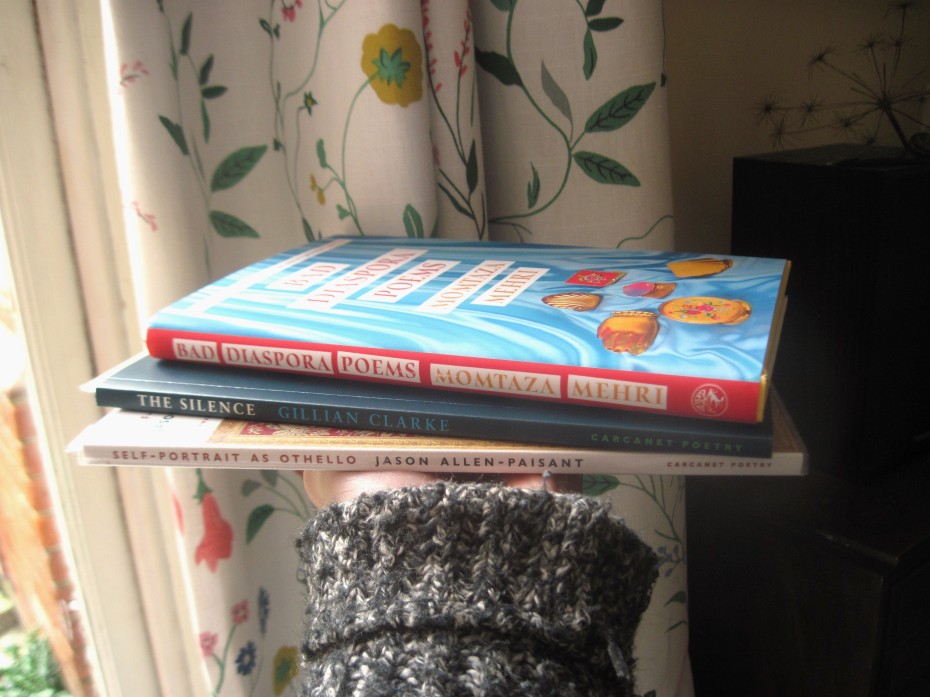

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest: Dylan Thomas Prize Blog Tour

Divisible by Itself and One is Kae Tempest’s 14th book, its title referring to the definition of prime numbers. I’d read one of their previous collections, Let Them Eat Chaos, and enjoyed the performance poetry rhythms. There is a similar feel here – urban settings; internal and end rhymes – but more experimentation with theme, style and tone. Often the poet crosses casual speech with a formal approach: “Body” is composed of two nontraditional sonnets, while “The loop” is a villanelle. I also noted a repeated phrase as a fulcrum between the two stanzas of “Do it for the joy.”

The prose piece “Swear” features a heartbroken nonbinary god in the wreckage of the Garden of Eden: “Groaning in the empty garden in a moment that lasted till now, the almighty swore they’d never love again. And the words of the oath were famine, pestilence, genocide, flood.” It’s not the only biblical allusion; “Flood” references Noah and one epigraph is from Isaiah. Climate breakdown is a source of background dread, with “Even the youths shall faint and be weary” a sarcastic response to people’s relief at young people’s engagement with the environment – “Manaic adults peddling hope. Surely / the kids will sort it.”

“Wind in the tall trees” takes on a rough tree shape on the page. There are a couple of apparent break-up scenes, but a tentative new relationship fuels tender, mildly erotic love poems (“Flight” and “Fig”). The alliteration in “Pride” evokes a gradual coming to grips with gender identity: “Pride by degrees. It’s relative / I’ve carried my shame / like a drunk friend dragged / through the days of my life. / Damn dysphoria.” “Cocoon” envisions a transformation, which comes to fruition in the final poem, the LGBTQ manifesto “Love song for queens, studs, butches, daddies, fags and all the other angels.” Here the poet hymns queer heroes, then joins them. “You are the strongest ones among us. Daring as you do to live. Wholly as you are. While the rest of us go straight // to pieces for what we can’t bear to admit we carry.” What a fantastic tease that enjambment is.

I found more variety than cohesion here, but Tempest is likely to attract readers who wouldn’t usually turn to poetry. This is one I’d recommend to fans of Surge by Jay Bernard and Some Integrity by Padraig Regan.

More favourite lines:

“Why not stick it out with this insane human being, rather than dig it all up just to replant yourself in a parallel hole.” (from “Absurd”)

“life’s a chance to do.

It’s all been done before. We make it new” (from “Morning”)

With thanks to Picador and Midas PR for the free copy for review.

I’ve reviewed Dylan Thomas Prize-longlisted poetry in several previous years as well:

- Eye Level by Jenny Xie

- If All the World and Love Were Young by Stephen Sexton

- Auguries of a Minor God by Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe

- Phantom Gang by Ciarán O’Rourke

I’ve now read three books from the longlist (the others are Bright Fear and Penance). The shortlist will be announced on 21 March, and the winner on 16 May. Look out for other bloggers’ posts between now and the 20th.

Women’s Prize 2024: Longlist Predictions vs. Wishes

This is the fourth year in a row that I’ve made predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist (the real thing comes out on Tuesday, 6 p.m. GMT). It shows how invested I’ve become in this prize in recent years. Like I did last year, I’ll give predictions, then wishes (no overlap this time!). My wishes are based on what I have already read and want to read. Although I kept tabs on publishers and ‘free entries’ for previous winners and shortlistees, I didn’t let quotas determine my selections. And while I kept in mind that there are two novelists on the judging panel, I don’t know enough about any of these judges’ taste to be able to tailor my predictions. My only thought was that they will probably appreciate good old-fashioned storytelling … but also innovative storytelling.

(There are two books – The List of Suspicious Things by Jennie Godfrey (= Joanna Cannon?) and Jaded by Ela Lee (this year’s Queenie) – that I only heard about as I was preparing this post and seem pretty likely, but I felt that it would be cheating for me to include them.)

Predictions

The Three of Us, Ore Agbaje-Williams

The Future, Naomi Alderman

The Storm We Made, Vanessa Chan

Penance, Eliza Clark

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

A House for Alice, Diana Evans

Piglet, Lottie Hazell

Pineapple Street, Jenny Jackson

Yellowface, R. F. Kuang

Biography of X, Catherine Lacey

Julia, Sandra Newman

The Vulnerables, Sigrid Nunez

Tom Lake, Ann Patchett

In Memory of Us, Jacqueline Roy

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C. Pam Zhang

Wish List

Family Lore, Elizabeth Acevedo

The Sleep Watcher, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

The Unfortunates, J. K. Chukwu

The Three Graces, Amanda Craig

Learned by Heart, Emma Donoghue

Service, Sarah Gilmartin

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Reproduction, Louisa Hall

Happiness Falls, Angie Kim

Bright Young Women, Jessica Knoll

A Sign of Her Own, Sarah Marsh

The Fetishist, Katherine Min

Hello Beautiful, Ann Napolitano

Mrs S, K Patrick

Romantic Comedy, Curtis Sittenfeld

Absolutely and Forever, Rose Tremain

If I’m lucky, I’ll get a few right from across these two lists; no doubt I’ll be kicking myself over the ones I considered but didn’t include, and marvelling at the ones I’ve never heard of…

What would you like to see on the longlist?

Appendix

(A further 50 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut. Like last year, I made things easy for myself by keeping an ongoing list of eligible novels in a file on my desktop.)

Everything Is Not Enough, Lola Akinmade Akerstrom

The Wind Knows My Name, Isabel Allende

Swanna in Love, Jennifer Belle

The Sisterhood, Katherine Bradley

The Fox Wife, Yangsze Choo

The Guest, Emma Cline

Speak to Me, Paula Cocozza

Talking at Night, Claire Daverley

Clear, Carys Davies

Bellies, Nicola Dinan

The Happy Couple, Naoise Dolan

In Such Tremendous Heat, Kehinde Fadipe

The Memory of Animals, Claire Fuller

Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Xochitl Gonzalez

Normal Women, Ainslie Hogarth

Sunburn, Chloe Michelle Howarth

Loot, Tania James

The Half Moon, Mary Beth Keane

Morgan Is My Name, Sophie Keetch

Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy

8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster, Mirinae Lee

August Blue, Deborah Levy

Winter Animals, Ashani Lewis

Rosewater, Liv Little

The Couples, Lauren Mackenzie

Tell Me What I Am, Una Mannion

She’s a Killer, Kirsten McDougall

The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, Claire McGlasson

Nightbloom, Peace Adzo Medie

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie Moore

The Lost Wife, Susanna Moore

Okay Days, Jenny Mustard

Parasol against the Axe, Helen Oyeyemi

The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, Soraya Palmer

The Lodgers, Holly Pester

Night Wherever We Go, Tracey Rose Peyton

The Mars House, Natasha Pulley

Playing Games, Huma Qureshi

Come and Get It, Kiley Reid

High Time, Hannah Rothschild

Commitment, Mona Simpson

Death of a Bookseller, Alice Slater

Bird Life, Anna Smail

Stealing, Margaret Verble

Help Wanted, Adelle Waldman

Temper, Phoebe Walker

Hang the Moon, Jeannette Walls

Moral Injuries, Christie Watson

Ghost Girl, Banana, Wiz Wharton

Speak of the Devil, Rose Wilding

This and That (The January Blahs)

The January blahs have well and truly arrived. The last few months of 2023 (December in particular) were too full: I had so much going on that I was always rushing from one thing to the next and worrying I didn’t have the time to adequately appreciate any of it. Now my problem is the opposite: very little to do, work or otherwise; not much on the calendar to look forward to; and the weather and house so cold I struggle to get up each morning and push past the brain fog to settle to any task. As I kept thinking to myself all autumn, there has to be a middle ground between manic busyness and boredom. That’s the head space where I’d like to be living, instead of having to choose between hibernation and having no time to myself.

At least these frigid January days are good for being buried in books. Unusually for me, I’m in the middle of seven doorstoppers, including King by Jonathan Eig (perfect timing as Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day), Wellness by Nathan Hill, and Babel by R.F. Kuang (a nominal buddy read with my husband).

Another is Carol Shields’s Collected Short Stories for a buddy rereading project with Marcie of Buried in Print. We’re partway through the first volume, Various Miracles, after a hiccup when we realized my UK edition had a different story order and, in fact, different contents – it must have been released as a best-of. We’ll read one volume per month in January–March. I also plan to join Heaven Ali in reading at least one Margaret Drabble book this year. I have The Waterfall lined up, and her Arnold Bennett biography lurking. Meanwhile, the Read Indies challenge, hosted by Karen and Lizzy in February, will be a great excuse to catch up on some review books from independent publishers.

Literary prize season will be heating up soon. I put all of the Women’s Prize (fiction and nonfiction!) dates on my calendar and I have a running list, in a file on my desktop, of all the novels I’ve come across that would be eligible for this year’s race. I’m currently reading two memoirs from the Nero Book Awards nonfiction shortlist. Last year it looked like the Folio Prize was set to replace the Costa Awards, giving category prizes and choosing an overall winner. But then another coffee chain, Caffè Nero, came along and picked up the mantle.

This year the Folio has been rebranded as The Writers’ Prize, again with three categories, which don’t quite overlap with the Costa/Nero ones. The Writers’ Prize shortlists just came out on Tuesday. I happen to have read one of the poetry nominees (Chan) and one of the fiction (Enright). I’m going to have a go at reading the others that I can source via the library. I’ll even try The Bee Sting given it’s on both the Nero and Writers’ shortlists (ditto the Booker) and I have a newfound tolerance of doorstoppers.

As for my own literary prize involvement, my McKitterick Prize manuscript longlist is due on the 31st. I think I have it finalized. Out of 80 manuscripts, I’ve chosen 5. The first 3 stood out by a mile, but deciding on the other 2 was really tricky. We judges are meeting up online next week.

I’m listening to my second-ever audiobook, an Audible book I was sent as a birthday gift: There Plant Eyes by M. Leona Godin. My routine is to find a relatively mindless data entry task to do and put on a chapter at a time.

There are a handful of authors I follow on Substack to keep up with what they’re doing in between books: Susan Cain, Jean Hannah Edelstein, Catherine Newman, Anne Boyd Rioux, Nell Stevens (who seems to have gone dormant?), Emma Straub and Molly Wizenberg. So far I haven’t gone for the paid option on any of the subscriptions, so sometimes I don’t get to read the whole post, or can only see selected posts. But it’s still so nice to ‘hear’ these women’s voices occasionally, right in my inbox.

My current earworms are from Belle and Sebastian’s Late Developers album, which I was given for Christmas. These lyrics from the title track – saved, refreshingly, for last; it’s a great strategy to end on a peppy song (an uplifting anthem with gospel choir and horn section!) instead of tailing off – feel particularly apt:

Live inside your head

Get out of your bed

Brush the cobwebs off

I feel most awake and alive when I’m on my daily walk by the canal. It’s such a joy to hear the birdsong and see whatever is out there to be seen. The other day there was a red kite zooming up from a field and over the houses, the sun turning his tail into a burnished chestnut. And on the opposite bank, a cuboid rump that turned out to belong to a muntjac deer. Poetry fragments from two of my bedside books resonated with me.

This is the earnest work. Each of us is given

only so many mornings to do it—

to look around and love

the oily fur of our lives,

the hoof and the grass-stained muzzle.

Days I don’t do this

I feel the terror of idleness

like a red thirst.

That is from “The Deer,” from Mary Oliver’s House of Light, and reminds me that it’s always worthwhile to get outside and just look. Even if what you’re looking at doesn’t seem to be extraordinary in any way…

Importance leaves me cold,

as does all the information that is classed as ‘news’.

I like those events that the centre ignores:

small branches falling, the slow decay

of wood into humus, how a puddle’s eye

silts up slowly, till, eventually,

the birds can’t bathe there. I admire the edge;

the sides of roads where the ragwort blooms

low but exotic in the traffic fumes;

the scruffy ponies in a scrubland field

like bits of a jigsaw you can’t complete;

the colour of rubbish in a stagnant leat.

There are rarest enjoyments, for connoisseurs

of blankness, an acquired taste,

once recognised, it’s impossible to shake,

this thirst for the lovely commonplace.

(from “Six Poems on Nothing,” III by Gwyneth Lewis, in Parables & Faxes)

This was basically a placeholder post because who knows when I’ll next finish any books and write about them … probably not until later in the month. But I hope you’ve found at least one interesting nugget!

What ‘lovely commonplace’ things are keeping you going this month?

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss) Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot. A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age. In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).