Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

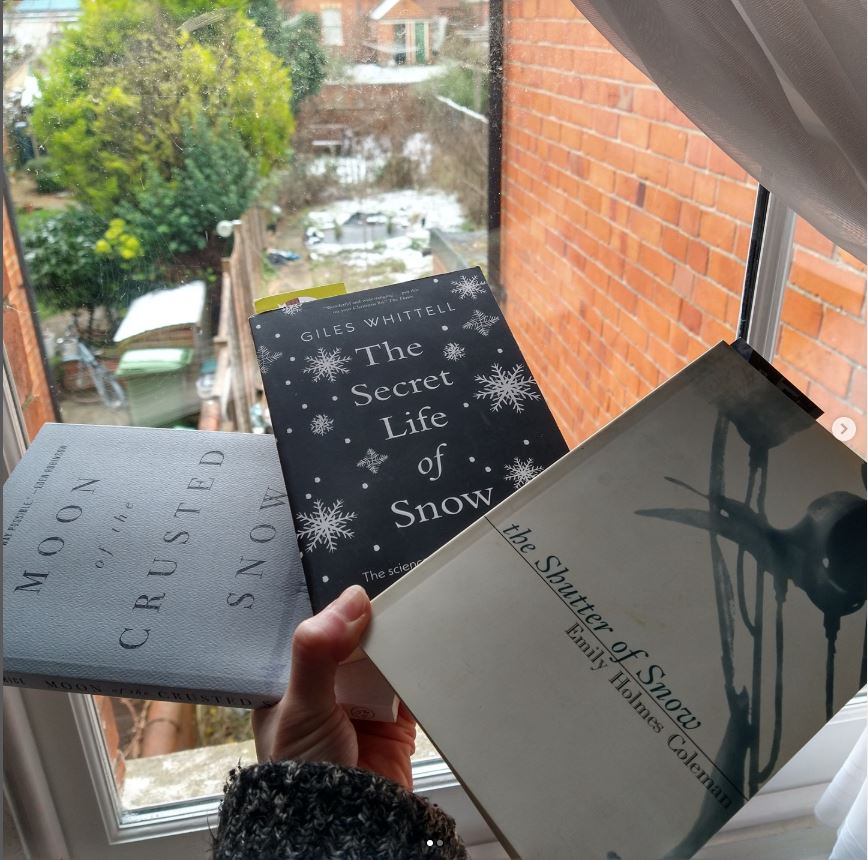

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

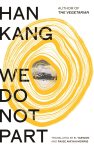

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

Reading Ireland Month, I: Donoghue, Longley, Tóibín

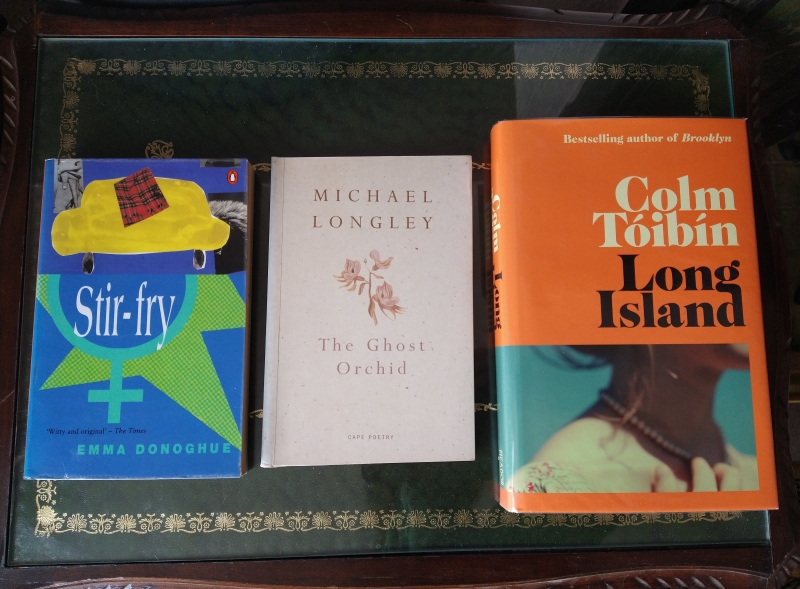

St. Patrick’s Day is a good occasion to compile my first set of contributions to Cathy’s Reading Ireland Month. Today I have an early novel by a favourite author, a poetry collection inspired by nature and mythology, and a sequel that I read for book club.

Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue (1994)

After enjoying Slammerkin so much last year, I decided to catch up on more of Donoghue’s way-back catalogue. She tends to alternate between contemporary and historical settings. I have a slight preference for the former, but she can excel at both; it really depends on the book. I reckon this was edgy for its time. Maria (whose name rhymes with “pariah”) arrives in Dublin for university at age 17, green in every way after a religious upbringing in the countryside. In response to a flat-share advert stipulating “NO BIGOTS,” she ends up living with Ruth and Jael (pronounced “Yale”), two mature students. Ruth is the mother hen, doing all the cooking and fretting over the others’ wellbeing; Jael is a wild, henna-haired 30-year-old prone to drinking whisky by the mug-full. Maria attends lectures, takes a job cleaning office buildings, and finds a friend circle through her backstage student theatre volunteering. She’s mildly interested in American exchange student Galway and then leather-clad Damien (until she realizes he has a boyfriend), but nothing ever goes further than a kiss.

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

Mostly, this short novel is a dance between the three central characters. The Irish-accented banter between them is a joy. Jael’s devil-may-care attitude contrasts with Ruth and Maria’s anxiety about how they are perceived by others. Ruth and Jael are figures in the Hebrew Bible and their devotion/boldness dichotomy is applicable to the characters here, too. The stereotypical markers of lesbian identity haven’t really changed, but had Donoghue written this now I think she would at least have made Maria a year older and avoided negativity about Damien and Jael’s bisexuality. At heart this is a sweet romance and an engaging picture of early 1990s feminism, but it doesn’t completely steer clear of predictability and I would have happily taken another 50–70 pages if it meant she could have fleshed out the characters and their interactions a little more. [Guess what was for my lunch this afternoon? Stir fry!] (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley (1995)

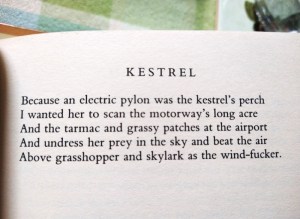

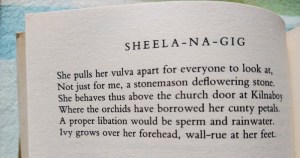

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

(Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

Long Island by Colm Tóibín (2024)

{SPOILERS in this one}

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

When news comes that Tony has impregnated a married woman and the cuckolded husband plans to leave the baby on the Fiorellos’ doorstep when the time arrives, Eilis checks out of the marriage. She uses her mother’s upcoming 80th birthday as an excuse to go back to Ireland for the summer. Here Eilis gets caught up in a love triangle with publican Jim Farrell, who was infatuated with her 20 years ago and still hasn’t forgotten her, and Nancy Sheridan, a widow who runs a fish and chip shop and has been Jim’s secret lover for a couple of years. Nancy has a vision of her future and won’t let Eilis stand in her way.

I felt for all three in their predicaments but most admired Nancy’s pluck. Ironically given the title, the novel spends more of its time in Ireland and only really comes alive there. There’s also a reference to Nora Webster – cute that Tóibín is trying out the Elizabeth Strout trick of bringing multiple characters together in the same fictional community. But, all told, this was just a so-so book. I’ve read 10 or so works by Tóibín now, in all sorts of genres, and with its plain writing this didn’t stand out at all. It got an average score from my book club, with one person loving it, a couple hating it, and most fairly indifferent. (Public library) ![]()

Another batch will be coming up before the end of the month!

Making Plans for a Return to Hay-on-Wye & A Book “Overhaul”

I was last in Hay-on-Wye for my 40th birthday (write-up here). We’ve decided 18 months is a decent length between visits such that we can go back and find enough turnover in the bookshops and changes around the town. The plan is to spend four nights there in early April, in a holiday cottage we’ve not stayed in before. It’s in Cusop, just back over the border into England, which means a pleasant (if not pouring with rain) walk over the fields into the town. Normally we go for just a night or two, so this longer ninth trip to Hay will allow us time to do more local exploring besides thoroughly trawling all the bookshops and rediscovering the best eateries on offer.

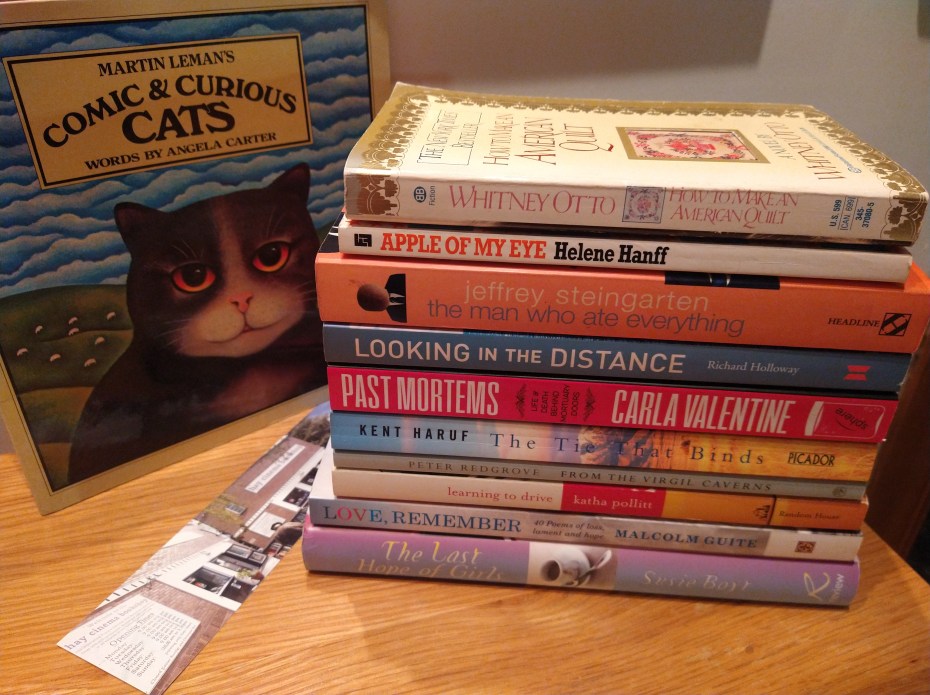

An Overhaul of Last Trip’s Book Purchases

Simon of Stuck in a Book has a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With his permission, I occasionally borrow the title and format to look back at what I’ve bought. Previous overhaul posts have covered pre-2020 Hay-on-Wye purchases, birthdays, the much-lamented Bookbarn International, and Northumberland. It’s been a good way of holding myself accountable for what I’ve purchased and reminding myself to read more from my shelves.

So, earlier this week I took a look back at the 16 new and secondhand books I acquired in Hay in October 2023. I was quickly dismayed: 18 months might seem like a long time, but as far as my shelves go it is more like the blink of an eye.

Read: Only 1 – Uh oh…

- Learning to Drive by Katha Pollitt

But also:

Partially read: 4

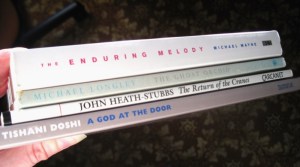

- A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi – Doshi is awesome. This is only my second of her poetry collections. I’ll finish it this month for Dewithon.

- Looking in the Distance by Richard Holloway – The problem with Holloway is that all of his books of recent decades are about the same – a mixture of mediations and long quotations from poetry – and I have one from last year on the review catch-up pile already. But I’m sure I’ll finish this at some point.

- The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley – No idea why I set this one aside, but I’ve put it back on a current stack.

- The Enduring Melody by Michael Mayne – I have this journal of his approaching death as one of my bedside books and read a tiny bit of it at a time. (Memento mori?)

Skimmed: 1

- Love, Remember: 40 Poems of Loss, Lament and Hope by Malcolm Guite – I enjoyed the poetry selection well enough but didn’t find that the author’s essays added value, so I’m donating this to my church’s theological library.

That left 10 still to read. Eager to make some progress, I picked up a quick win, Comic & Curious Cats, illustrated in an instantly recognizable blocky folk art style by Martin Leman (I also have his Twelve Cats for Christmas, a stocking present I gave my husband this past year) and with words by Angela Carter. Yes, that Angela Carter! It’s picture book size but not really, or not just, for children. Each spread of this modified abecedarian includes a nonsense poem that uses the letter as much as possible: the cat’s name, where they live, what they eat, and a few choice adjectives. I had to laugh at the E cat being labelled “Elephantine.” Who knows, there might be some good future cat names in here: Basil and Clarissa? Francesca and Gordon? Wilberforce? “I love my cat with an XYZ [zed] … There is really nothing more to be said.” Charming. (Secondhand purchase – Hay-on-Wye Booksellers) ![]()

Total still unread: 9

Luckily, I’m still keen to read all of them. I’ll start with the two I purchased new, So Happy for You by Celia Laskey, a light LGBTQ thriller about a wedding (from Gay on Wye with birthday money from friends, a sweet older lesbian couple – so it felt appropriate to use their voucher there!), and Past Mortems by Carla Valentine, a memoir set at a mortuary (remainder copy from Addymans); as well as a secondhand novel, The Tie that Binds by Kent Haruf (Hay-on-Wye Booksellers) and the foodie essays of The Man Who Ate Everything by Jeffrey Steingarten (Cinema).

Then, if I still haven’t read them before the trip (who am I kidding…), I’ll pack for the car a few small volumes that will fit neatly into my handbag: Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff, How to Make an American Quilt by Whitney Otto, and one of the poetry collections.

Literary Wives Club: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (2022)

Like pretty much every other woman over 30 on the planet, I read Lessons in Chemistry when it first came out. I was happy for my book club to select it for a later month when I was away; it made a decent selection but I had no need to revisit it, then or now. I think it still holds the record for the longest reservation queue in my library system. I enjoyed this feel-good feminist story well enough but found certain elements hokey, such as Six-Thirty the dog’s preternatural intelligence and Elizabeth Zott’s neurodivergent-like bluntness and lack of sentimentality.

My original review: Elizabeth Zott is a scientist through and through, applying a chemist’s mindset to her every venture, including cooking, rowing and single motherhood in the 1950s. When she is fired from her job in a chemistry lab and gets a gig as a TV cooking show host instead, she sees it as her mission to treat housewives as men’s intellectual equals, but there are plenty of people who don’t care for her unusual methods and free thinking. I was reminded strongly of The Atomic Weight of Love and The Rosie Project, as well as novels by Katherine Heiny and especially John Irving with the deep dive into backstory and particular pet subjects, and the orphan history for Zott’s love interest. This was an enjoyable tragicomedy. You have to cheer for the triumphs she and other female characters win against the system of the time. However, the very precocious child (and dog) stretch belief, and the ending was too pat for me. (Public library) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Elizabeth is deeply in love with Calvin Evans yet refuses to be his wife. She spurns marriage because she correctly intuits that it will limit her prospects, this being the 1960s. “I’m going to be a scientist. Successful women scientists don’t marry,” she tells her mother. Forasmuch as she assumes her television audience to be traditional housewives, she rejects their situation for herself. A single mother, a minor celebrity, a scientific researcher: none of these roles would be compatible with marriage. (Though there’s another ultimate reason why she stays unmarried.)

A supporting character, her neighbour Harriet, offers a counterpoint or cautionary tale. She’s trapped in a marriage to an odious man she despises. “Because while she was stuck forever being Mrs. Sloane—she was a Catholic—she never wanted to turn into a Mr. Sloane.”

Almost all of the books we read for the club, whether contemporary or historical, present marriage in at least a somewhat negative light, or warn that there are many things that can go wrong…

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in June: The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham. This is the first play we’ve done and my first Maugham in a while, so I’m looking forward to it.

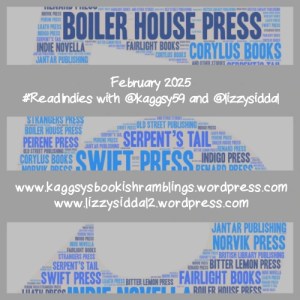

The Moomins and the Great Flood (#Moomins80) & Poetry (#ReadIndies)

To mark the 80th anniversary of Tove Jansson’s Moomins books, Kaggsy, Liz et al. are doing a readalong of the whole series, starting with The Moomins and the Great Flood. I received a copy of Sort Of Books’ 2024 reissue edition for Christmas, so I was unknowingly all set to take part. I also give quick responses to a couple of collections I read recently from two favourite indie poetry publishers in the UK, The Emma Press and Carcanet Press. These are reads 9–11 for Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge.

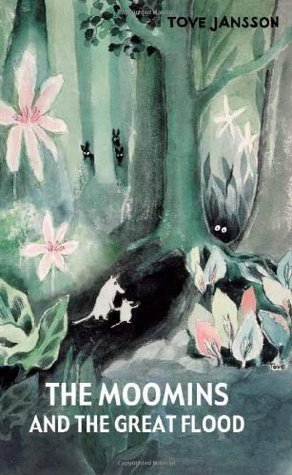

The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson (1945; 1991)

[Translated from the Swedish by David McDuff]

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

I read my first Moomins tale in 2011 and have been reading them out of order and at random ever since; only one remains unread. Unfortunately, I did not find it rewarding to go right back to the beginning. At barely 50 pages (padded out by the Cottrell-Boyce introduction and an appendix of Jansson’s who’s-who notes), this story feels scant, offering little more than a hint of the delightful recurring characters and themes to come. Jansson had not yet given the Moomins their trademark rounded hippo-like snouts; they’re more alien and less cute here. It’s like seeing early Jim Henson drawings of Garfield before he was a fat cat. That just ain’t right. I don’t know why I’d assumed the Moomins are human-size. When you see one next to a marabou stork you realize how tiny they are; Jansson’s notes specify 20 cm tall. (Gift)

The Emma Press Anthology of Homesickness and Exile, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

Departures, arrivals; longing, regret: these are classic themes from Ovid (the inspiration for this volume) onward. Holly Hopkins and Rachel Long were additional familiar names for me to see in the table of contents. My two favourite poems were “The Restaurant at One Thousand Feet” (about the CN Tower in Toronto) by John McCullough, whose collections I’ve enjoyed before; and “The Town” by Alex Bell, which personifies a closed-minded Dorset community – “The town wraps me tight as swaddling … When I came to the town I brought things with me / from outside, and the town took them / for my own good.” Home is complicated – something one might spend an entire life searching for, or trying to escape. (New purchase from publisher)

Gold by Elaine Feinstein (2000)

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I wanted to live with a bit of flash and brio,

rather than huddle behind ghetto gates.

The last two stanzas are especially memorable:

Poor Mozart was so much less fortunate.

My only sadness is to think of him, a pauper,

lying in his grave, while I became

Professor of Italian literature.

Nobody living can predict their fate.

I moved across the cusp of a new age,

to reach this present hour of privilege.

On this earth, luck is worth more than gold.

Politics, manners, morals all evolve

uncertainly. Best then to be bold.

Best then to be bold!

Of the discrete “Lyrics” that follow, I most liked “Options,” about a former fiancé (“who can tell how long we would have / burned together, before turning to ash?”) and “Snowdonia,” in which she’s surprised when a memory of her father resurfaces through a photograph. Talking to the Dead was more consistently engaging. (Secondhand purchase – Bridport Old Books, 2023)

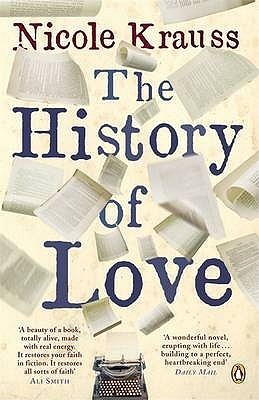

Adventures in Rereading: The History of Love by Nicole Krauss for Valentine’s Day

Special Valentine’s edition. Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet manage a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the ninth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024!

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library)

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Finishing my reread during a coffee date in Hungerford this morning.

My original rating (2011): ![]()

When I first read this, I mostly considered it in comparison to Krauss’s former husband Jonathan Safran Foer’s work. (I’ve long since read everything by both of them.) I noted then that it

has a lot of elements in common with Everything is Illuminated, such as a preoccupation with Eastern European and Jewish ancestry, quirky methods of narration including multiple voices, and a sweet humour that lies alongside such heart-rending stories of family and loss that tears are never far from your eyes. Leo Gursky and Alma Singer are delightful and distinct characters. I wasn’t sure about the missing/plagiarized/mistaken The History of Love itself; the ruined copies, the different translations, the way the manuscript was constantly changing hands – all this was intriguing, but the book itself was a postmodern jumble of magic realism and pointless meanderings of thought.

Dang, I was harsh! But admirably pithy about the plot. It’s intriguing that I’ve successfully reread Krauss but failed with Foer when I attempted Everything is Illuminated again in 2020. Reading the first, 9/11-set section of Confessions by Catherine Airey, I’ve also been recalling his Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and thinking it probably wouldn’t stand up to a reread either. I suspect I’d find it mawkish, especially with its child narrator. Alma evades that trap, perhaps by being that little bit older, though she sounds young because of how geeky and sheltered she is.

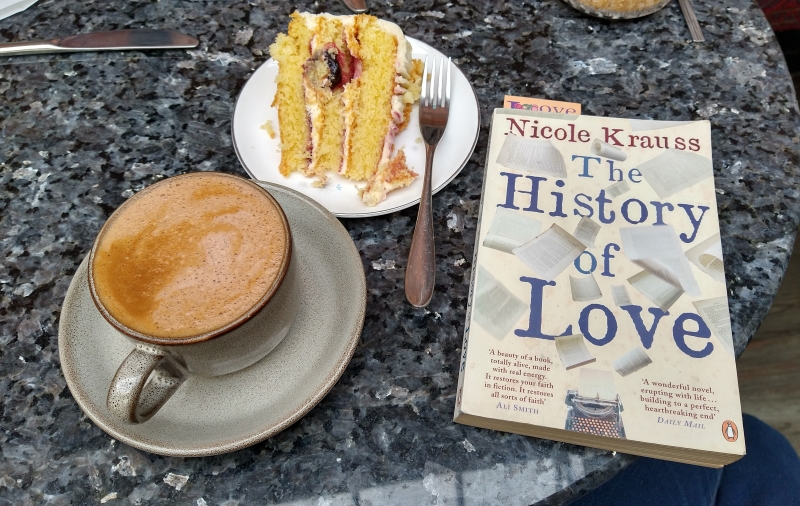

Winter Reads, I: Michael Cunningham & Helen Moat

It’s been feeling springlike in southern England with plenty of birdsong and flowers, yet cold weather keeps making periodic returns. (For my next instalment of wintry reads, I’ll try to attract some snow to match the snowdrops by reading three “Snow” books.) Today I have a novel drawing on a melancholy Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale and a nature/travel book about learning to appreciate winter.

The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham (2014)

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

Of course, Cunningham takes inspiration, thematically and linguistically, from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale about love and conversion, most obviously in an early dreamlike passage about Tyler letting snow swirl into the apartment through the open windows:

He returns to the window. If that windblown ice crystal meant to weld itself to his eye, the transformation is already complete; he can see more clearly now with the aid of this minuscule magnifying mirror…

I was most captivated by the early chapters of the novel, picking it up late one night and racing to page 75, which is almost unheard of for me. The rest took me significantly longer to get through, and in the intervening five weeks or so much of the detail has evaporated. But I remember that I got Chris Adrian and Julia Glass vibes from the plot and loved the showy prose. (And several times while reading I remarked to people around me how ironic it was that these characters in a 2014 novel are so outraged about Dubya’s re-election. Just you all wait two years, and then another eight!)

I fancy going on a mini Cunningham binge this year. I plan to recommend The Hours for book club, which would be a reread for me. Otherwise, I’ve only read his travel book, Land’s End. I own a copy of Specimen Days and the library has Day, but I’d have to source all the rest secondhand. Simon of Stuck in a Book is a big fan and here are his rankings. I have some great stuff ahead! (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

While the Earth Holds Its Breath: Embracing the Winter Season by Helen Moat (2024)

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

There were many incidents and emotions I could relate to here – a walk on the canal towpath always makes me feel better, and the car-heavy lifestyle I resume on trips to America feels unnatural.

Days are where we must live, but it didn’t have to be a prison of house and walls. I needed the rush of air, the slap of wind on my cheeks. I needed to feel alive. Outdoors.

I’d never liked the rain, but if I were to grow to love winters on my island, I had to learn to love wet weather, go out in it.

What can there be but winter? It belongs to the circle of life. And I belonged to winter, whether I liked it or not. Indoors, or moving from house to vehicle and back to house again, I lost all sense of my place on this Earth. This world would be my home for just the smallest of moments in the vastness of time, in the turning of the seasons. It was a privilege, I realised.

However, the content is repetitive such that the three-year cycle doesn’t add a lot and the same sorts of pat sentences about learning to love winter recur. Were the timeline condensed, there might have been more of a focus on the more interesting travel segments, which also include France and Scotland. So many have jumped on the Wintering bandwagon, but Katherine May’s book felt fresh in a way the others haven’t.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

Goss’s first child, Ella, died at 16 months of a rare heart condition, Severe Ebstein’s Anomaly. This collection is in three parts, the first recreating vignettes from her daughter’s short life, the purgatorial central section dwelling in the aftermath of grief, and the third summoning the courage to have another baby. “So extraordinary was your sister’s / short life, it’s hard for me to see // a future for you. I know it’s there, … yet I can’t believe // my fortune”. The close focus on physical artefacts and narrow slices of memory wards away mawkishness. The poems are sweetly affecting but never saccharine. “I kept a row of lilac-buttoned relics / in my wardrobe. Hand-knitted proof, something/ to haul my sorry lump of heart and make it blaze.” (New purchase from Bookshop UK with buyback credit)

Goss’s first child, Ella, died at 16 months of a rare heart condition, Severe Ebstein’s Anomaly. This collection is in three parts, the first recreating vignettes from her daughter’s short life, the purgatorial central section dwelling in the aftermath of grief, and the third summoning the courage to have another baby. “So extraordinary was your sister’s / short life, it’s hard for me to see // a future for you. I know it’s there, … yet I can’t believe // my fortune”. The close focus on physical artefacts and narrow slices of memory wards away mawkishness. The poems are sweetly affecting but never saccharine. “I kept a row of lilac-buttoned relics / in my wardrobe. Hand-knitted proof, something/ to haul my sorry lump of heart and make it blaze.” (New purchase from Bookshop UK with buyback credit)  I can’t remember where I came across this in the context of recommended family memoirs, but the title and premise were enough to intrigue me. I’d not previously heard of Maitland, who at the time was known for a TV investigative reporting show called Watchdog exposing con artists. The irony: he was soon to discover that his own mother was a con artist. By chance, he met a journalist who recalled a scandal involving his parents’ old folks’ homes. Maitland toggles between flashbacks to his earlier life and fragments from his investigation, which involved archival research but mostly interviews with his estranged sister, his mother’s ex-husbands, and more.

I can’t remember where I came across this in the context of recommended family memoirs, but the title and premise were enough to intrigue me. I’d not previously heard of Maitland, who at the time was known for a TV investigative reporting show called Watchdog exposing con artists. The irony: he was soon to discover that his own mother was a con artist. By chance, he met a journalist who recalled a scandal involving his parents’ old folks’ homes. Maitland toggles between flashbacks to his earlier life and fragments from his investigation, which involved archival research but mostly interviews with his estranged sister, his mother’s ex-husbands, and more. If you mostly know Mantel for her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, her debut novel, a black comedy, will come as a surprise. Two households become entangled in sordid ways in 1974. The Axons, Evelyn and her intellectually disabled adult daughter, Muriel, live around the corner from Florence Sidney, who still resides in her family home and whose brother Colin lives nearby with his wife and three children (the fourth is on the way). Colin is having an affair with Muriel’s social worker, Isabel Field. Evelyn is dismayed to realize that Muriel has, somehow, fallen pregnant.

If you mostly know Mantel for her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, her debut novel, a black comedy, will come as a surprise. Two households become entangled in sordid ways in 1974. The Axons, Evelyn and her intellectually disabled adult daughter, Muriel, live around the corner from Florence Sidney, who still resides in her family home and whose brother Colin lives nearby with his wife and three children (the fourth is on the way). Colin is having an affair with Muriel’s social worker, Isabel Field. Evelyn is dismayed to realize that Muriel has, somehow, fallen pregnant.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of  That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s. Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.