Summer Reading, Part II: Beanland, Watters; O’Farrell, Oseman Rereads

Apparently the UK summer officially extends to the 22nd – though you’d never believe it from the autumnal cold snap we’re having just now – so that’s my excuse for not posting about the rest of my summery reading until today. I have a tender ancestry-inspired story of a Jewish family’s response to grief, a bizarre YA fantasy comic, and two rereads, one a family story from one of my favourite contemporary authors and the other the middle instalment in a super-cute graphic novel series.

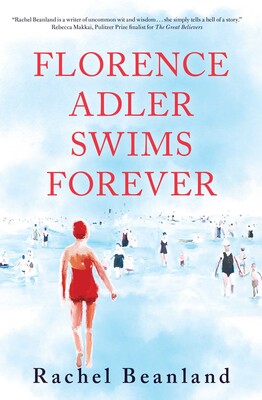

Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland (2020)

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

The particulars can be chalked up to family history: this really happened; the Gussie character was Beanland’s grandmother, and the author believes her great-great-aunt Florence died of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It’s intriguing to get glimpses of Jewish ritual, U.S. anti-Semitism and early concern over Nazism, but I was less engaged with other subplots such as Fannie’s husband Isaac’s land speculation in Florida. There’s a satisfying queer soupcon, and Beanland capably inhabits all of the perspectives and the bereaved mindset. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Lumberjanes: Campfire Songs by Shannon Watters et al. (2020)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library) ![]()

And the rereads:

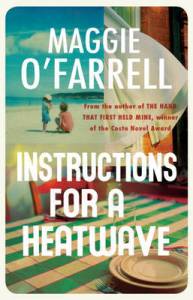

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell (2013)

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I had forgotten the two major reveals, but this time they didn’t seem as important as the overall sense of decisions with unforeseen consequences. O’Farrell was using extreme weather as a metaphor for risk and cause-and-effect (“a heatwave will act upon people. It lays them bare, it wears down their guard. They start behaving not unusually but unguardedly”), and it mostly works. But this wasn’t a top-tier O’Farrell on a reread. (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Average: ![]()

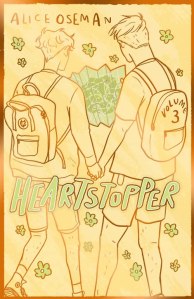

Heartstopper: Volume 3 by Alice Oseman (2020)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library) ![]()

Any final “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

Making Plans for a Return to Northumberland & A Book “Overhaul”

It’s just over three years since our terrific trip to Northumberland. We enjoyed ourselves so much that, when casting around for somewhere within the country to spend a week in September before the university term starts for my husband, we decided to go back later this week. This time we’re renting a holiday cottage in Berwick and travelling by train and bus instead of car – a decision that has already been complicated by rail replacement buses, but we’re making it work. The plan is to explore Berwick and Bamburgh; revisit Alnwick, the Farne Islands, and Lindisfarne (Holy Island); and venture into Scotland for a day trip. We’ll also stay with friends in York on the way up and back and attend York’s annual beer festival with them.

An Overhaul of Last Trip’s Book Purchases

Simon of Stuck in a Book runs a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With his permission, I occasionally borrow the title and format to look back at what I’ve bought. Previous overhaul posts have covered Hay-on-Wye, birthdays, and the much-missed Bookbarn International. It’s a good way of holding myself accountable for what I’ve purchased and reminding myself to read more from my shelves.

So, earlier this summer, I took a look back at the whopping 33 new and secondhand books I acquired in Northumberland (and en route) in July 2021; they are all pictured in my trip write-up post.

Had already read: 2

- How Far Can You Go by David Lodge

- Leaving Church by Barbara Brown Taylor – It’s on my shelf for rereading.

Have read since then: 22 – I cannot tell you how proud I am of this number! A full 2/3!

- Until the Real Thing Comes Along by Elizabeth Berg (see below)

- The Girl Aquarium by Jen Campbell

- The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

- Home Life by Alice Thomas Ellis

- Talking to the Dead by Elaine Feinstein

- Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn

- The End We Start From by Megan Hunter

- The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

- Spring by Karl Ove Knausgaard

- No Time to Spare by Ursula K. Le Guin

- The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws

- An Advent Calendar by Shena Mackay

- Christmas Holiday by W. Somerset Maugham

- Birds of America by Lorrie Moore

- Thinking Again by Jan Morris

- Emerald by Ruth Padel

- Dear George by Helen Simpson

- Intimations by Zadie Smith

- Filthy Animals by Brandon Taylor

- North with the Spring by Edwin Way Teale

- Female Friends by Fay Weldon

- Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto

Plus…

Partially read: 4

- A Keeper of Sheep by William Carpenter

- Nature Cure by Richard Mabey

- Vida by Marge Piercy

- The Truants by Kate Weinberg

Skimmed: 1 (A Childhood in Scotland by Christian Miller)

Gave away unread: 1 (Wolf Winter by Cecilia Ekback)

Total still unread: 7

Total no longer owned: 11 (resold, gifted or donated to the Little Free Library) – Getting rid of at least 1/3 of what I read seems like a pretty solid ratio.

I surveyed the pile of books still unread or only partly read and picked up a few to read beforehand or on the way back to Northumberland. I managed to finish one:

Until the Real Thing Comes Along by Elizabeth Berg (1999)

I think of Berg as Anne Tyler lite, likely to appeal to readers of Sue Miller, Catherine Newman, and Maggie O’Farrell. I’d read five of her novels and they are all at least moderately enjoyable, with Talk Before Sleep the best and Open House and The Pull of the Moon in a second tier. But this was pretty annoying and cliched. The plot is straight out of that Rupert Everett–Madonna movie The Next Best Thing. Patty is madly in love with her friend Ethan but, darn it, he’s gay. She’s also 36 and desperate for a baby. She can’t see another way to get one, so Ethan agrees to impregnate her. Works first time! Everything goes perfectly with the pregnancy, and he says he’ll try to act straight so they can move to Minneapolis to raise the baby. Reality does set in, but only very late on. My main problem was Patty: always complaining, putting no effort into her real estate career, and oblivious to when her parents are struggling. Ethan’s experience losing friends to AIDS is shoehorned in through one histrionic paragraph. This got better as it went on, but certainly wasn’t what I’d call fresh and convincing.

I think of Berg as Anne Tyler lite, likely to appeal to readers of Sue Miller, Catherine Newman, and Maggie O’Farrell. I’d read five of her novels and they are all at least moderately enjoyable, with Talk Before Sleep the best and Open House and The Pull of the Moon in a second tier. But this was pretty annoying and cliched. The plot is straight out of that Rupert Everett–Madonna movie The Next Best Thing. Patty is madly in love with her friend Ethan but, darn it, he’s gay. She’s also 36 and desperate for a baby. She can’t see another way to get one, so Ethan agrees to impregnate her. Works first time! Everything goes perfectly with the pregnancy, and he says he’ll try to act straight so they can move to Minneapolis to raise the baby. Reality does set in, but only very late on. My main problem was Patty: always complaining, putting no effort into her real estate career, and oblivious to when her parents are struggling. Ethan’s experience losing friends to AIDS is shoehorned in through one histrionic paragraph. This got better as it went on, but certainly wasn’t what I’d call fresh and convincing. ![]()

and am partway through another:

Sorry to Disrupt the Peace by Patrick [Patty Yumi at the time of publication] Cottrell – An unusual voice-driven novel about a Korean adoptee mourning her brother’s death by suicide. I’m not sure I’ll stay the course.

I’m packing for the train:

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium by Gerald Durrell

A House Unlocked by Penelope Lively

Vida by Marge Piercy

…along with plenty of other books in progress!

A Review for PKD Awareness Day: The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall

Today is PKD Awareness Day. Because the author and I both have polycystic kidney disease, I’m doing something I rarely do and reprinting an early review of mine that has already appeared on Shelf Awareness. I could hardly believe it when I was trawling through the list of review book offers and saw that Eiren Caffall also has PKD, then even more astonished to learn that it is a major theme in her memoir, which also weaves in marine biology and environmental concerns. An altogether intriguing book that, of course, held personal interest for me.

The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall

Eiren Caffall’s debut is an ardent elegy for her illness-haunted family and for the ailing marine environments that inspire her.

For centuries, the author’s family has been subject to “the Caffall Curse.” Polycystic kidney disease, a degenerative genetic condition, causes fluid-filled cysts to proliferate in a person’s enlarged kidneys. PKD can involve pain, fatigue, high blood pressure, kidney failure, and a heightened risk of brain aneurysm. Given Caffall’s paternal family history, she expected to die before age 50.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

In 2014, Caffall, then a single mother, took her nine-year-old son, Dex, on vacation to the Gulf of Maine. During the trip, she had a fall that prompted a seizure, and she and Dex were evacuated from Monhegan Island by Coast Guard ship. Although no further seizures ensued and no clear cause emerged, the crisis served as a wake-up call, reminding her of how serious PKD is and that it might afflict her son as well.

The book draws fascinating connections between personal experiences and ecological threats. Caffall structures her story as a gallery of endangered marine animals such as the Longfin Inshore Squid and Humpback Whale, tracing their history and exposing the dangers they face in degraded environments. Red tides (massive algal blooms) and floods are apt metaphors for physical trials: “the Sound was dying, hypoxic … from an overwhelm of nutrients flooding an ecosystem—nitrogen, phosphorus, imbalanced saline—the same things that overwhelm a body when kidneys can no longer filter blood properly.”

Re-created scenes enliven accounts of family illness and therapeutic developments. The lyrical hybrid narrative, informed by scientific journals and government publications, is as impassioned about restoring the environment as it is about ensuring equality of access to health care. Personal and species extinction are just cause for “permanent mourning,” Caffall writes, but adapting to change keeps hope alive.

(Coming out in the USA from Row House Publishing on October 15th)

Posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

[I couldn’t help but compare family members’ trajectories. Like her father, my mother was on dialysis for a time before getting a transplant, from her cousin. Like her aunt, my uncle died of a brain aneurysm, which is an associated risk. It sounds like Caffall has been much more severely affected than I have thus far. She is 53 and on Tolvaptan, a cutting-edge drug that slows the growth of cysts and thus the decline in kidney function. But even within families, the disease course is so varied. A cousin of mine was in her thirties when she had a transplant, whereas I am still very much in the early stages.]

A shout-out to the PKD Foundation in the States and the PKD Charity here in the UK.

A related post: In 2017 I reviewed four books for World Kidney Day.

From the supermarket last week: a plum that wanted to be a kidney.

Literary Wives Club: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

This is one of those classics I’ve been hearing about for decades and somehow never read – until now. Right from the start, I could spot its influence on African American writers such as Toni Morrison. Hurston deftly reproduces the all-Black milieu of Eatonville, Florida, bringing characters to life through folksy speech and tying into a venerable tradition through her lyrical prose. As the novel opens, Janie Crawford, forty years old but still a looker, sets tongues wagging when she returns to town “from burying the dead.” Her friend Pheoby asks what happened and the narrative that unfolds is Janie’s account of her three marriages.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER!}

- To protect Janie’s reputation and prospects, her grandmother, who grew up in the time of slavery, marries Janie off to an old farmer, Logan Killicks, at age 16. He works her hard and treats her no better than one of his animals.

- She then runs off with handsome, ambitious Joe Starks. [A comprehension question here: was Janie technically a bigamist? I don’t recall there being any explanation of her getting an annulment or divorce.] He opens a general store and becomes the town mayor. Janie is, again, a worker, but also a trophy wife. While the townspeople gather on the porch steps to shoot the breeze, he expects her to stay behind the counter. The few times we hear her converse at length, it’s clear she’s wise and well-spoken, but in the 20 years they are together Joe never allows her to come into her own. He also hits her. “The years took all the fight out of Janie’s face.” When Joe dies of kidney failure, she is freer than before: a widow with plenty of money in the bank.

- Nine months after Joe’s death, Janie is courted by Vergible Woods, known to all as “Tea Cake.” He is about a decade younger than her (Joe was a decade older, but nobody made a big deal out of that), but there is genuine affection and attraction between them. Tea Cake is a lovable scoundrel, not to be trusted around money or other women. They move down to the Everglades and she joins him as an agricultural labourer. The difference between this and being Killicks’ wife is that Janie takes on the work voluntarily, and they are equals there in the field and at home.

In my favourite chapter, a hurricane hits. The title comes from this scene and gives a name to Fate. Things get really melodramatic from this point, though: during their escape from the floodwaters, Tea Cake has to fend off a rabid dog to save Janie. He is bitten and contracts rabies which, untreated, leads to madness. When he comes at Janie with a pistol, she has to shoot him with a rifle. A jury rules it an accidental death and finds Janie not guilty.

I must admit that I quailed at pages full of dialogue – dialect is just hard to read in large chunks. Maybe an audiobook or film would be a better way to experience the story? But in between, Hurston’s exposition really impressed me. It has scriptural, aphoristic weight to it. Get a load of her opening and closing paragraphs:

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Here was peace. [Janie] pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

There are also beautiful descriptions of Janie’s state of mind and what she desires versus what she feels she has to settle for. “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.” She envisions happiness as sitting under a pear tree; bees buzzing in the blossom above and all the time in the world for contemplation. (It was so pleasing when I realized this is depicted on the Virago Modern Classics cover.)

I was delighted that the question of having babies simply never arises. No one around Janie brings up motherhood, though it must have been expected of her in that time and community. Her first marriage was short and, we can assume, unconsummated; her second gradually became sexless; her third was joyously carnal. However, given that both she and her mother were born of rape, she may have had traumatic associations with pregnancy and taken pains to prevent it. Hurston doesn’t make this explicit, yet grants Janie freedom to take less common paths.

What with the symbolism, the contrasts, the high stakes and the theatrical tragedy, I felt this would be a good book to assign to high school students instead of or in parallel with something by John Steinbeck. I didn’t fall in love with it in the way Zadie Smith relates in her introduction, but I did admire it and was glad to finally experience this classic of African American literature. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- A marriage without love is miserable. Marriage is not a cure for loneliness.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the unmated? Did marriage compel love like the sun the day?

(These are rhetorical questions, but the answer is NO.)

- Every marriage is different. But it works best when there is equality of labour, status and finances. Marriage can change people.

Pheoby says to Janie when she confesses that she’s thinking about marrying Tea Cake, “you’se takin’ uh awful chance.” Janie replies, “No mo’ than Ah took befo’ and no mo’ than anybody else takes when dey gits married. It always changes folks, and sometimes it brings out dirt and meanness dat even de person didn’t know they had in ’em theyselves.”

Later Janie says, “love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch. Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

This was a perfect book to illustrate the sorts of themes we usually discuss!

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in December: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (about Sylvia Plath)

Three on a Theme: Books on Communes by Crossman, Heneghan & Twigg

Communal living always seems like a great idea but rarely works out well. Why? The short answer: Because people. A longer answer: Political ideals are hard to live out in the everyday when egos clash, practical arrangements become annoying, and lines of privacy or autonomy get crossed. All three books I review today are set in the aftermath of utopian failure. Susanna Crossman, who grew up in an English commune, looks back at 15 years of an abnormal childhood. The community in Birdeye is set to collapse after two founding members announce their departure, leaving one ageing woman and her disabled daughter. And in Spoilt Creatures, from a decade’s distance, Iris narrates the disastrous downfall of Breach House.

Home Is Where We Start: Growing up in the Fallout of the Utopian Dream by Susanna Crossman

For Crossman’s mother, “the community” was a refuge, a place to rebuild their family’s life after divorce and the death of her oldest daughter in a freak accident. For her three children, it initially was a place of freedom and apparent equality between “the Adults” and “the Kids” – who were swiftly indoctrinated into hippie opinions on the political matters of the day. “There is no difference between private and public conversations, between the inside and the outside. No euphemisms. Vaginas are discussed over breakfast alongside domestic violence and nuclear bombs.” Crossman’s present-tense recreation of her precocious eight-year-old perspective is canny, as when she describes watching Charles and Diana’s wedding on television:

It was beautiful, but I know marriage is a patriarchal institution, a capitalist trap, a snare. You can read about it in Spare Rib, or if you ask community members, someone will tell you marriage is legalized rape. It is a construction, and that means it’s not natural, and is part of the social reproduction of gender roles and women’s unpaid domestic labour.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

The author is now a clinical arts therapist, so her recreation is informed by her knowledge of healthy child development and the long-term effects of trauma. She knows the Kids suffered from a lack of routine and individually expressed love. Community rituals, such as opening Christmas presents in the middle of a circle of 40 onlookers, could be intimidating rather than welcoming. Her molestation and her sister’s rape (when she was nine years old, on a trip to India ‘supervised’ by two other adults from the community) were cloaked in silence.

Crossman weaves together memoir and psychological theory as she examines where the utopian impulse comes from and compares her own upbringing with how she tries to parent her three daughters differently at home in France. Through vignettes based on therapy sessions with patients, she shows how play and the arts can help. (I’d forgotten that I’ve encountered Crossman’s writing before, through her essay on clowning for the Trauma anthology.) I somewhat lost interest as the Kids grew into teenagers. It’s a vivid and at times rather horrifying book, but the author doesn’t resort to painting pantomime villains. Behind things were good intentions, she knows, and there is nuance and complexity to her account. It’s a great mix of being back in the moment and having the hindsight to see it all clearly.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Birdeye by Judith Heneghan

Like Crossman’s community, the Birdeye Colony is based in a big crumbling house in the countryside – but this time in the USA; the Catskills of upstate New York, to be precise. Liv Ferrars has been the de facto leader for nearly 50 years, since she was a young mother to twins. Now she’s a sixty-seven-year-old breast cancer survivor. To her amazement, her book, The Attentive Heart, still attracts visitors, “bringing their problems, their pain and loneliness, hoping to be mended, made whole.”

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

It’s a bit of a sleepy book, with a touch of suspense as secrets emerge from Birdeye’s past. I was slightly reminded of May Sarton’s Kinds of Love. I most appreciated the character study of Liv and her very different relationships with her daughters, who are approaching fifty: Mary is a capable lawyer in London, while Rose suffered oxygen deprivation at birth and is severely intellectually disabled. Since Liv’s illness, Mary has pressured her to make plans for Rose’s future and, ultimately, her own. The duty of care we bear towards others – blood family; the chosen family of friends and comrades, even pets – arises as a major theme. I’d recommend this to those who love small-town novels.

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

& 20 Books of Summer, #20:

Spoilt Creatures by Amy Twigg

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the free copy for review.

On this topic, I have also read:

Novels:

Arcadia by Lauren Groff

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne

On my TBR:

O Sinners by Nicole Cuffy

We Burn Daylight by Bret Anthony Johnston

Nonfiction:

Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk

August Releases: Sarah Manguso (Fiction), Sarah Moss (Memoir), and Carl Phillips (Poetry)

Today I feature a new-to-me poet and two women writers whose careers I’ve followed devotedly but whose latest books – forthright yet slippery; their genre categories could easily be reversed – I found very emotionally difficult to read. Gruelling, almost, but admirable. Many rambling thoughts ensue. Then enjoy a nice poem.

Liars by Sarah Manguso

As part of a profile of Manguso and her oeuvre for Bookmarks magazine, I wrote a synopsis and surveyed critical opinion; what follow are additional subjective musings. I’ve read six of her nine books (all but the poetry and an obscure flash fiction collection) and I esteem her fragmentary, aphoristic prose, but on balance I’m fonder of her nonfiction. Had Liars been marketed as a diary of her marriage and divorce, Manguso might have been eviscerated for the indulgence and one-sided presentation. With the thinnest of autofiction layers, is it art?

Jane recounts her doomed marriage, from the early days of her relationship with John Bridges to the aftermath of his affair and their split. She is a writer and academic who sacrifices her career for his financially risky artistic pursuits. Especially once she has a baby, every domestic duty falls to her, while he keeps living like a selfish stag and gaslights her if she tries to complain, bringing up her history of mental illness. The concise vignettes condense 14+ years into 250 pages, which is a relief because beneath the sluggish progression is such repetition of type of experiences that it could feel endless. John’s last name might as well be Doe: The novel presents him – and thus all men – as despicable and useless, while women are effortlessly capable and, by exhausting themselves, achieve superhuman feats. This is what heterosexual marriage does to anyone, Manguso is arguing. Indeed, in a Guardian interview she characterized this as a “domestic abuse novel,” and elsewhere she has said that motherhood can be unlinked from patriarchy, but not marriage.

Let’s say I were to list my every grievance against my husband from the last 17+ years: every time he left dirty clothes on the bedroom floor (which is every day); every time he loaded the dishwasher inefficiently (which is every time, so he leaves it to me); every time he failed to seal a packet or jar or Tupperware properly (which – yeah, you get the picture) – and he’s one of the good guys, bumbling rather than egotistical! And he’d have his own list for me, too. This is just what we put up with to live with other people, right? John is definitely worse (“The difference between John and a fascist despot is one of degree, not type”). But it’s not edifying, for author or reader. There may be catharsis to airing every single complaint, but how does it help to stew in bitterness? Look at everything I went through and validate my anger.

There are bright spots: Jane’s unexpected transformation into a doting mother (but why must their son only ever be called “the child”?), her dedication to her cat, and the occasional dark humour:

So at his worst, my husband was an arrogant, insecure, workaholic, narcissistic bully with middlebrow taste, who maintained power over me by making major decisions without my input or consent. It could still be worse, I thought.

Manguso’s aphoristic style makes for many quotably mordant sentences. My feelings vacillated wildly, from repulsion to gung-ho support; my rating likewise swung between extremes and settled in the middle. I felt that, as a feminist, I should wholeheartedly support a project of exposing wrongs. It’s easy to understand how helplessness leads to rage, and how, considering sunk costs, a partner would irrationally hope for a situation to improve. So I wasn’t as frustrated with Jane as some readers have been. But I didn’t like the crass sexual language, and on the whole I agreed with Parul Sehgal’s brilliant New Yorker review that the novel is so partial and the tone so astringent that it is impossible to love. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

And a quote from the Moss memoir (below) to link the two books: “Homes are places where vulnerable people are subject to bullying, violence and humiliation behind closed doors. Homes are places where a woman’s work is never done and she is always guilty.”

20 Books of Summer, #19:

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I’ve reviewed this memoir for Shelf Awareness (it’s coming out in the USA from Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 22nd) so will only give impressions, in rough chronological order:

Sarah Moss returns to nonfiction – YES!!!

Oh no, it’s in the second person. I’ve read too much of that recently. Fine for one story in a collection. A whole book? Not so sure. (Kirsty Logan got away with it, but only because The Unfamiliar is so short and meant to emphasize how matrescence makes you other.)

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

Once she starts discussing her childhood reading – what it did for her then and how she views it now – the book really came to life for me. And she very effectively contrasts the would-be happily ever after of generally getting better after eight years of disordered eating with her anorexia returning with a vengeance at age 46 – landing her in A&E in Dublin. (Oh! when she reads War and Peace over and over on a hospital bed and defiantly uses the clean toilets on another floor.) This crisis is narrated in the third person before a return to second person.

The tone shifts throughout the book, so that what threatens to be slightly cloying in the childhood section turns academically curious and then, somehow, despite the distancing pronouns, intimate. So much so that I found myself weeping through the last chapters over this lovely, intelligent woman’s ongoing struggles. As an overly cerebral person who often thinks it’s pesky to have to live in a body, I appreciated her probing of the body/mind divide; and as she tracks where her food issues came from, I couldn’t help but think about my sister’s years of eating disorders and my mother’s fear that it was all her fault.

Beyond Moss’s usual readers, I’d also recommend this to fans of Laura Freeman’s The Reading Cure and Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place.

Overall: shape-shifting, devastating, staunchly pragmatic. I’m not convinced it all hangs together (and I probably would have ended it at p. 255), but it’s still a unique model for transmuting life into art. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Will I remember individual poems? Unlikely. But the sense of chilly, clear-eyed reflection, yes. (Sample poem below) ![]()

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

Record of Where a Wind Was

Wave-side, snow-side,

little stutter-skein of plovers

lifting, like a mind

of winter—

We’d been walking

the beach, its unevenness

made our bodies touch,

now and then, at

the shoulders mostly,

with that familiarity

that, because it sometimes

includes love, can

become confused with it,

though they remain

different animals. In my

head I played a game with

the waves called Weapon

of Choice, they kept choosing

forgiveness, like the only

answer, as to them

it was, maybe. It’s a violent

world. These, I said, I choose

these, putting my bare hands

through the air in front of me.

Any other August releases you’d recommend?

#MoominWeek & #WITMonth, II: Moominpappa at Sea by Tove Jansson

My first two reads for Women in Translation month were Catalan and French novellas. With this third one I’m tying in with Moomin Week, hosted by Chris and Mallika in honour of Paula of Book Jotter. Happy nuptials to Paula! Not a blogger I’ve interacted with before, but I welcomed the excuse to finish a book I started a few months ago. I’ve actually reviewed five Moomin books here before: Moominvalley in November, Moominland Midwinter, Tales from Moominvalley, Moominsummer Madness, and Finn Family Moomintroll. (It’s also the third year in a row that I’ve reviewed something by Jansson for WIT Month.)

Appropriate reading at sea (on a ferry to France)

I didn’t grow up with the Moomins, but as an adult I’ve come to love the series for how it lovingly depicts everyday disasters and neuroses and, beneath the whimsical adventures, offers an extra level of thoughtfulness for adult readers. The setting of this one was particularly appropriate. Here’s the opening paragraph:

One afternoon at the end of August, Moominpappa was walking about in his garden feeling at a loss. He had no idea what to do with himself, because it seemed everything there was to be done had already been done or was being done by somebody else.

The sense of being ‘all at sea’ persists for Pappa and the other characters even after they sail to ‘his’ island in the Gulf of Finland, drawn to see in person the lighthouse he has kept as a model on the shelf. They arrive to find the island mysteriously empty and the facilities derelict. Moomintroll goes exploring alone and meets intriguing “sea-horses” that look more equine than marine. Nature is alive and resistant to ‘improvements’ such as Moominmamma trying to tame the wildness with her rose bushes and apple trees. The forest also seems to be retreating from the sea; everything fears it, in fact. The sullen fisherman is no help, and the hulking Groke seems to be a metaphor for depression as well as a literal monster.

The sense of being ‘all at sea’ persists for Pappa and the other characters even after they sail to ‘his’ island in the Gulf of Finland, drawn to see in person the lighthouse he has kept as a model on the shelf. They arrive to find the island mysteriously empty and the facilities derelict. Moomintroll goes exploring alone and meets intriguing “sea-horses” that look more equine than marine. Nature is alive and resistant to ‘improvements’ such as Moominmamma trying to tame the wildness with her rose bushes and apple trees. The forest also seems to be retreating from the sea; everything fears it, in fact. The sullen fisherman is no help, and the hulking Groke seems to be a metaphor for depression as well as a literal monster.

There is a sense of everything being awry, and by the close that’s only partially rectified. Pappa ends with conflicting feelings towards the island: proprietary yet timorous. I imagine this is based on Jansson’s own experiences living on a Finnish island (see also The Summer Book). This wasn’t among my favourite Moomin books, but I always appreciate the juxtaposition of the domestic and wild, the cosy and the melancholy. Just two more for me to find now (I’ve read them all in random order): The Moomins and the Great Flood and Moominpappa’s Memoirs.

[Translated from the Swedish by Kingsley Hart] (University library) ![]()

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

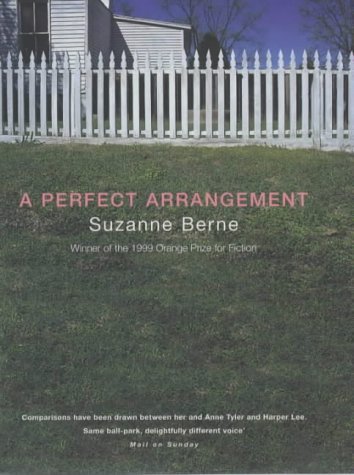

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

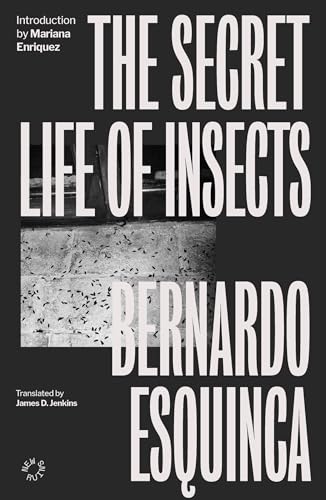

Mysterious manuscripts and therapy appointments also recur – there’s a scholarly Freudianism at play here. In the novella-length “Demoness,” friends at a twentieth high school reunion recount traumatic experiences from adolescence (not your average campfire fare). “Our traumas define us much more than our happy moments, [Ignacio, a Jesuit priest] thought. They’re the real revelations about ourselves.” Masturbation features heavily in this and in “Pan’s Noontide,” which has both of Arturo’s wives disappear in connection with an ecoterrorism cult. I occasionally found the content a bit macho and gross-out, and wished the women could be more than just sexualized supporting figures in male fantasies.

Mysterious manuscripts and therapy appointments also recur – there’s a scholarly Freudianism at play here. In the novella-length “Demoness,” friends at a twentieth high school reunion recount traumatic experiences from adolescence (not your average campfire fare). “Our traumas define us much more than our happy moments, [Ignacio, a Jesuit priest] thought. They’re the real revelations about ourselves.” Masturbation features heavily in this and in “Pan’s Noontide,” which has both of Arturo’s wives disappear in connection with an ecoterrorism cult. I occasionally found the content a bit macho and gross-out, and wished the women could be more than just sexualized supporting figures in male fantasies.