Christmas Reading and Book Haul

I recently read two novels set in the week of Christmas. Both were good reminders to appreciate the family that you have because whatever your dysfunctional situation, it could probably be much worse.

Christmas Holiday by W. Somerset Maugham (1939): Twenty-three-year-old Charley Mason heads to Paris on Christmas Eve to see his old friend Simon and live it up in the big city. First thing, Simon takes him to a brothel, where Charley dances with topless Russian prostitute “Princess Olga.” Before things go any further, he ducks out to attend a Mass he happened to get tickets for, and she begs to accompany him. When Lydia (for that is her real name) starts weeping during the service, he takes her back to his hotel and listens with rapt horror as she tells him the sordid story of how her husband, a petty criminal named Robert Berger, murdered a man for fun and ended up in prison overseas. From here on, Charley’s primary feeling for Lydia is pity and any desire he had is neutralized. Simon, too, is fascinated with the Berger case for what it reveals about essential human egoism. The chaste relationship with Lydia and the intensity of the interactions with Simon made me wonder if there was covert homoeroticism here. It was interesting, shortly after my Paris trip, to read something about how sleazy it is rather than how magical. (Secondhand purchase)

Christmas Holiday by W. Somerset Maugham (1939): Twenty-three-year-old Charley Mason heads to Paris on Christmas Eve to see his old friend Simon and live it up in the big city. First thing, Simon takes him to a brothel, where Charley dances with topless Russian prostitute “Princess Olga.” Before things go any further, he ducks out to attend a Mass he happened to get tickets for, and she begs to accompany him. When Lydia (for that is her real name) starts weeping during the service, he takes her back to his hotel and listens with rapt horror as she tells him the sordid story of how her husband, a petty criminal named Robert Berger, murdered a man for fun and ended up in prison overseas. From here on, Charley’s primary feeling for Lydia is pity and any desire he had is neutralized. Simon, too, is fascinated with the Berger case for what it reveals about essential human egoism. The chaste relationship with Lydia and the intensity of the interactions with Simon made me wonder if there was covert homoeroticism here. It was interesting, shortly after my Paris trip, to read something about how sleazy it is rather than how magical. (Secondhand purchase)

Flight by Lynn Steger Strong (2022): I couldn’t resist the setup: three grown-up siblings and their families meet at the one brother’s house in upstate New York to celebrate their first Christmas since their mother died. The novel takes place over just four days, the 22nd through Christmas Day, but Strong pumps in a lot of backstory about the sibling dynamic and the three marriages. The late Helen has already ascended into legend, and her coastal home in Florida is a bargaining chip. Tess, Martin’s lawyer wife, approaches the problem practically: sell it and split the profits three ways. Henry, an environmentalist artist, wants to sell the land to the state to be part of a nature preserve. Kate, the sentimental one, wants to live in the house herself but isn’t sure she and Josh can afford to buy her brothers out. At first I thought this was going to be a slightly irksome story of privileged white people and their ‘problems’, but there is a biracial character and an ex-heroin addict and her daughter also become key characters. As the family build igloos, bake pies and plan the perfect photo shoot, offences are simmering under the surface (“Mostly they resent each other from a comfortable enough distance that they might call it love”). These all fade, though, when a child goes missing. I was reminded subtly of Ann Patchett’s work, but more, with the environmental and parenting themes, of Ramona Ausubel and Megan Mayhew Bergman. I’d read more by Strong. (Public library)

Flight by Lynn Steger Strong (2022): I couldn’t resist the setup: three grown-up siblings and their families meet at the one brother’s house in upstate New York to celebrate their first Christmas since their mother died. The novel takes place over just four days, the 22nd through Christmas Day, but Strong pumps in a lot of backstory about the sibling dynamic and the three marriages. The late Helen has already ascended into legend, and her coastal home in Florida is a bargaining chip. Tess, Martin’s lawyer wife, approaches the problem practically: sell it and split the profits three ways. Henry, an environmentalist artist, wants to sell the land to the state to be part of a nature preserve. Kate, the sentimental one, wants to live in the house herself but isn’t sure she and Josh can afford to buy her brothers out. At first I thought this was going to be a slightly irksome story of privileged white people and their ‘problems’, but there is a biracial character and an ex-heroin addict and her daughter also become key characters. As the family build igloos, bake pies and plan the perfect photo shoot, offences are simmering under the surface (“Mostly they resent each other from a comfortable enough distance that they might call it love”). These all fade, though, when a child goes missing. I was reminded subtly of Ann Patchett’s work, but more, with the environmental and parenting themes, of Ramona Ausubel and Megan Mayhew Bergman. I’d read more by Strong. (Public library)

And now for the promised Christmas book haul.

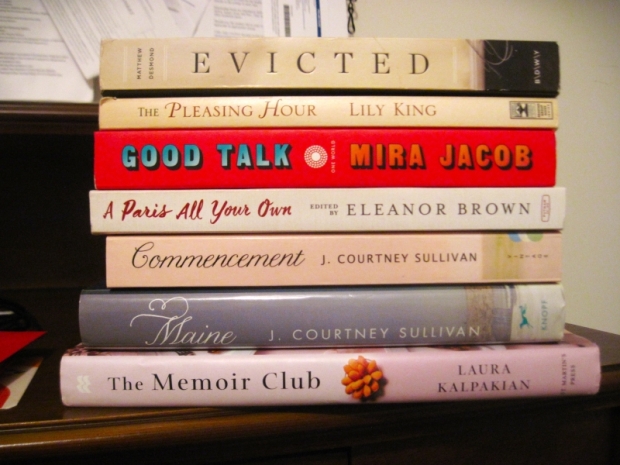

Here’s what I bought with store credit at 2nd & Charles while in the States for my sister’s graduation with her bachelor’s in nursing.

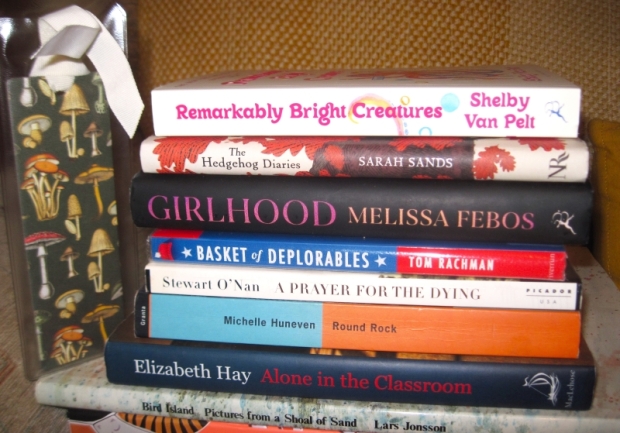

We got to do some fun family Christmassy things while I was there for 10 days, then I flew back to the UK into Christmas Eve and got to do actual Christmas with my in-laws. It’s been a whirlwind of a month!

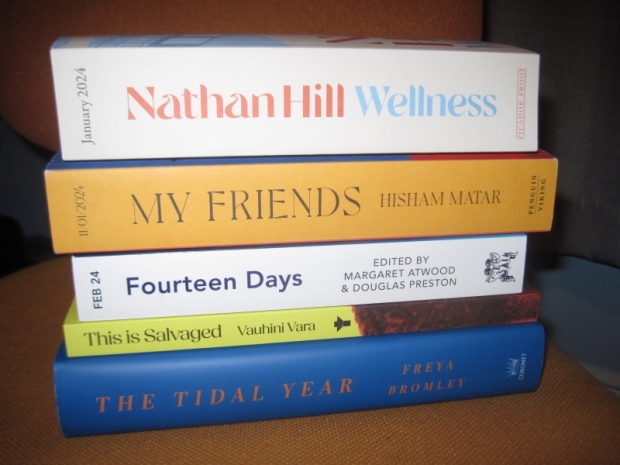

I had this book post waiting for me when I got back.

And received these for Christmas!

December Releases: Rebecca, Not Becky & You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

The last month of the year is generally thin on the ground for new books, but here are two December U.S. releases I reviewed early for Shelf Awareness. One is a fun and timely novel about race relations and the other an autobiographical poetry collection about asexuality and chronic illness. Below are excerpts with a link to the full text for one. Both:

Rebecca, Not Becky by Christine Platt and Catherine Wigginton Greene

Two women navigate the nuances of racism in their affluent Northern Virginia community. Rebecca Myland shed the nickname “Becky” when it became cultural shorthand for clueless white ladies. She desperately wants to do the right thing, including making the perfect home for her husband and daughters and being a model white ally, leading the school’s diversity committee and antiracist book club.

Two women navigate the nuances of racism in their affluent Northern Virginia community. Rebecca Myland shed the nickname “Becky” when it became cultural shorthand for clueless white ladies. She desperately wants to do the right thing, including making the perfect home for her husband and daughters and being a model white ally, leading the school’s diversity committee and antiracist book club.

De’Andrea Whitman reluctantly gave up her law career and Atlanta support system to move to Rolling Hills. It’s the best place for the family, given her husband Malik’s new job and the proximity to his mother’s top-notch dementia care facility. However, she is painfully aware that their daughter, Nina, may be the only Black student at the private school. De’Andrea’s therapist, Dr. Jones, challenges her to try to make one white friend.

The two protagonists have more in common than they realize. When the diversity committee’s controversial pet project of getting a statue of a Confederate general removed from the local park makes national news, the resulting ruckus threatens their fragile friendship. It’s a hugely enjoyable novel reminiscent of Terry McMillan and Curtis Sittenfeld that nonetheless takes a hard look at prejudice and performative allyship.

(And I love the title because my mother and one aunt always tried to call me Becky, but I hate that nickname!)

You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis by Kelly Weber

The poet feels marked by “failure to want” and by recurring medical complaints—severe Crohn’s disease and menorrhagia, initially dismissed by a doctor as menstrual cramps. In “Blood Firsts,” she compares her first period with the later coming-of-age moment of realizing she was asexual. She describes herself as a teenage wallflower, aware of a same-sex pull but unsure what, if anything, to do about it. The series of lyrical attempted definitions in “Queerplatonic” show her in love with a female friend. Anatomy and nature supply the book’s interlocking metaphors. Animals appear frequently, but often as roadkill or taxidermied trophies. The structure varies, with prose paragraphs, columns, and text moving up the page. The rich stylistic palette (rhetorical questions, footnotes, second person, a call-and-response format) and sonic arsenal (alliteration, wordplay, anaphora) make for a courageous, unforgettable collection. (Forthcoming)

The poet feels marked by “failure to want” and by recurring medical complaints—severe Crohn’s disease and menorrhagia, initially dismissed by a doctor as menstrual cramps. In “Blood Firsts,” she compares her first period with the later coming-of-age moment of realizing she was asexual. She describes herself as a teenage wallflower, aware of a same-sex pull but unsure what, if anything, to do about it. The series of lyrical attempted definitions in “Queerplatonic” show her in love with a female friend. Anatomy and nature supply the book’s interlocking metaphors. Animals appear frequently, but often as roadkill or taxidermied trophies. The structure varies, with prose paragraphs, columns, and text moving up the page. The rich stylistic palette (rhetorical questions, footnotes, second person, a call-and-response format) and sonic arsenal (alliteration, wordplay, anaphora) make for a courageous, unforgettable collection. (Forthcoming)

A Quick Look Back at Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell for #LiteraryWives

I read Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize winner, Hamnet, at its release in 2020. Unfortunately, it has been my least favourite of her novels (I’ve read all but My Lover’s Lover now), and it turns out 3.5 years is too soon to reread and appreciate anew. But I had a quick skim back through, this time focusing on the central marriage and the question we ask for the Literary Wives online book club:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

From my original review: O’Farrell imagines the context of the death of William Shakespeare’s son Hamnet and the effect it had on the playwright’s work – including, four years later, Hamlet. Curiously, she has decided never to mention Shakespeare by name in her novel, so he remains a passive, shadowy figure seen only in relation to his wife and children – he’s referred to as “the father,” “the Latin tutor” or “her husband.” Instead, the key characters are his wife, Agnes (most will know her as Anne, but Agnes was the name her father, Richard Hathaway, used for her in his will), and Hamnet himself.

It is refreshing, especially for the time period, to have the wife’s experience and perspective be primary, and the husband in the background to the extent of being unnamed. Both, however, blame themselves for not being there when 11-year-old Hamnet fell ill with what O’Farrell posits was the Plague. Shakespeare was away in London with his theatre company; Agnes was off tending her bees. Shakespeare is only present in flashbacks – in which he morphs from eager tutor to melancholy drinker – until three-quarters of the way through the novel, when he returns to Stratford, too late. All he can do then is carry his son’s corpse.

I have heard it said many times that few marriages survive the death of a child. And for a while that looks like it will be the case here, too:

Her husband takes her arm as they reach the gate; she turns to look at him and it is as if she has never seen him before, so odd and distorted and old do his features seem. Is it their long separation, is it grief, is it all the tears? she wonders, as she regards him. Who is this person next to her, claiming her arm, holding it to him?

How were they to know that Hamnet was the pin holding them together? That without him they would all fragment and fall apart, like a cup shattered on the floor?

With his earnings, Shakespeare buys the family a new house, but never moves them to London as he once intended. He continues to stay away for long periods at a time, leaving Agnes to her grief. When, four years after Hamnet’s death, Agnes and their daughters learn that he has written a play about a character called Hamlet, they feel betrayed, but Agnes goes to a performance and her anger melts as she recognizes her son. “It is him. It is not him. … grown into a near-man, as he would be now, had he lived, on the stage, walking with her son’s gait, talking in her son’s voice, speaking words written for him by her son’s father.”

Although O’Farrell leaves it there, creating uncertainty about the couple’s future, she implies that the play has been the saving of both of them. For Shakespeare, it was the outlet for his grief. For Agnes, it was the proof she needed that he loved their son, grieved him as bitterly as she did, and still remembers him. That seems to be enough to hold them together.

While her next novel, The Marriage Portrait, which I liked a lot more as historical fiction goes, might seem on the surface better suited for this club, Hamnet was in fact perfect for the prompt, revealing an aspect I don’t recall looking at before: the strain that a child’s illness and death can place on a marriage. At my first reading I found the prose flat and detached, to the point of vagueness, and thought there was anachronistic language and unsubtle insertion of research. This time, I was more aware of how the deliberate evenness softens the emotion, making it more bearable – though, still, I have a friend who gave up reading this partway because she found it too raw.

See also Kay’s and Naomi’s responses!

The next book, for March 2024, will be Mrs. March by Virginia Feito.

The Story Girl by L. M. Montgomery (1911) #ReadingStoryGirl

Six months after the Jane of Lantern Hill readalong, Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah Emsley have chosen an earlier work by Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Story Girl, and its sequel The Golden Road, for November buddy reading.

The book opens one May as brothers Felix and Beverley King are sent from Toronto to Prince Edward Island to stay with an aunt and uncle while their father is away on business. Beverley tells us about their thrilling six months of running half-wild with their cousins Cecily, Dan, Felicity, and Sara Stanley – better known by her nickname of the Story Girl, also to differentiate her from another Sara – and the hired boy, Peter. This line gives a sense of the group’s dynamic: “Felicity to look at—the Story Girl to tell us tales of wonder—Cecily to admire us—Dan and Peter to play with—what more could reasonable fellows want?”

Felicity is pretty and domestically inclined; Sara knows it would be better to be useful like Felicity, but all she has is her storytelling ability. Some are fantasy (“The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess”); some are local tales that have passed into folk memory (“How Betty Sherman Won a Husband”). Beverley is in raptures over the Story Girl’s orations: “if voices had colour, hers would have been like a rainbow. It made words live. … we had listened entranced. I have written down the bare words of the story, as she told it; but I can never reproduce the charm and colour and spirit she infused into it. It lived for us.”

The cousins’ adventures are gently amusing and quite tame. They all write down their dreams in notebooks. Peter debates which church denomination to join and the boys engage in a sermon competition. Pat the cat has to be rescued from bewitching, and receives a dose of medicine in lard he licks off his paws and fur. The Story Girl makes a pudding with sawdust instead of cornmeal (reminding me of Anne Shirley and the dead mouse in the plum pudding). Life consistently teaches lessons in humility, as when they are all duped by Billy Robinson and his magic seeds, which he says will change whatever each one most resents – straight hair, plumpness, height; and there is a false alarm about the end of the world.

I found the novel fairly twee and realized at a certain point that I was skimming over more than I was reading. As was my complaint about Jane of Lantern Hill, there is a predictable near-death illness towards the end. The descriptions of Felicity and the Story Girl are purple (“when the Story Girl wreathed her nut-brown tresses with crimson leaves it seemed, as Peter said, that they grow on her—as if the gold and flame of her spirit had broken out in a coronal”); I had to remind myself that this reflects on Beverley more so than on Montgomery. From Naomi’s review of The Golden Road, I think that would be more to my taste because it has a clear plot rather than just stringing together pleasant but mostly forgettable anecdotes.

Still, it’s been fun to discover some of L. M. Montgomery’s lesser-known work, and there are sweet words about cats and the seasons:

“I am very good friends with all cats. They are so sleek and comfortable and dignified. And it is so easy to make them happy.”

“The beauty of winter is that it makes you appreciate spring.”

This effectively captures the long, magical summer days of childhood. I thought about when I was a kid and loved trips up to my mother’s hometown in upstate New York, where her brothers still lived. I was in awe of the Judd cousins’ big house, acres of lawn and untold luxuries such as Nintendo and a swimming pool. I guess I was as star-struck as Beverley. (University library)

Various Miracles was published in 1985, when Shields was 50. She was still a decade from finding success for her best-known works, The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party, and so far had published poetry, criticism and several novels. The title story’s string of coincidences and the final story, sharing a title with one of her poetry volumes (“Others”), neatly express the book’s concerns with chance and how we relate to other people and imagine their lives. I was disoriented by first starting the UK paperback (Fourth Estate, 1994). I had no idea it’s a selection; a number of the stories appear in the Collected volume under her next title, The Orange Fish. Before I realized that, I’d read two interlopers, including “Hazel,” which also spotlights the theme of coincidence. “Everything is an accident, Hazel would be willing to say if asked. Her whole life is an accident, and by accident she has blundered into the heart of it,” stumbling into a sales career during her widowhood.

Various Miracles was published in 1985, when Shields was 50. She was still a decade from finding success for her best-known works, The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party, and so far had published poetry, criticism and several novels. The title story’s string of coincidences and the final story, sharing a title with one of her poetry volumes (“Others”), neatly express the book’s concerns with chance and how we relate to other people and imagine their lives. I was disoriented by first starting the UK paperback (Fourth Estate, 1994). I had no idea it’s a selection; a number of the stories appear in the Collected volume under her next title, The Orange Fish. Before I realized that, I’d read two interlopers, including “Hazel,” which also spotlights the theme of coincidence. “Everything is an accident, Hazel would be willing to say if asked. Her whole life is an accident, and by accident she has blundered into the heart of it,” stumbling into a sales career during her widowhood. By contrast, my favourites went deep with a few characters, or reflected on the writer’s craft. “Fragility” has a couple moving from Toronto to Vancouver, starting a new life and looking for a house that gives off good vibrations (not “a divorce house”). The slow reveal of the catalyzing incident with their son is devastating. With “Others,” Shields (or editors) saved the best for last. On honeymoon in France, Robert and Lila help a fellow English-speaking couple by cashing a check for them. Every year thereafter, Nigel and Jane send them a Christmas card, winging its way from England to Canada. Robert and Lila romanticize these people they met all of once. The plot turns on what is in those pithy 1–2-sentence annual updates versus what remains unspoken. “Love so Fleeting, Love so Fine,” too, involves filling in an entire backstory for an unknown character. Another favourite was “Poaching,” about friends touring England and picking up hitchhikers, whose stories they appropriate.

By contrast, my favourites went deep with a few characters, or reflected on the writer’s craft. “Fragility” has a couple moving from Toronto to Vancouver, starting a new life and looking for a house that gives off good vibrations (not “a divorce house”). The slow reveal of the catalyzing incident with their son is devastating. With “Others,” Shields (or editors) saved the best for last. On honeymoon in France, Robert and Lila help a fellow English-speaking couple by cashing a check for them. Every year thereafter, Nigel and Jane send them a Christmas card, winging its way from England to Canada. Robert and Lila romanticize these people they met all of once. The plot turns on what is in those pithy 1–2-sentence annual updates versus what remains unspoken. “Love so Fleeting, Love so Fine,” too, involves filling in an entire backstory for an unknown character. Another favourite was “Poaching,” about friends touring England and picking up hitchhikers, whose stories they appropriate.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”  House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)  36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)  God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.”

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.” Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.”

Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.” The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of  After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity.

After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity. We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s

We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s  This was consciously based on George Orwell’s

This was consciously based on George Orwell’s

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]  If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]  This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

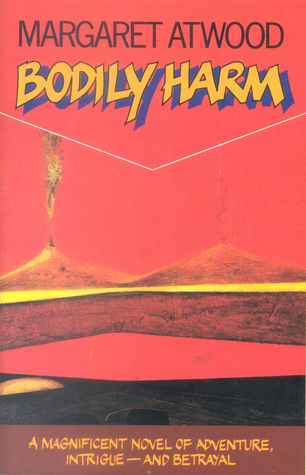

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment.

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment. Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.

Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.