Library Checkout, October 2020

ALL of my reservations seemed to come in at once this month, so I’ve been busy reading the recent releases that are requested after me. Soon I’ll amass a pile of short books to consider reading for Novellas in November. While searching through shelves and boxes of children’s picture books for reserved titles, I often come across ones I can’t resist, especially if they feature animals. I borrow a few most weeks and enjoy reading them back at home over a cup of tea.

I would be delighted to have other bloggers – and not just book bloggers, either – join in this meme. Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (which runs on the last Monday of every month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram (@bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout).

I rate most of the books I read or skim, and include links to reviews not already featured on the blog.

READ

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive by Stephanie Land

- 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs

- An Event in Autumn by Henning Mankell

- The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer

- English Pastoral: An Inheritance by James Rebanks

- Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid – Success on the second try!

- How to Be Both by Ali Smith

- Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth

- Night by Elie Wiesel

+ Children’s picture books (don’t worry, these don’t count towards my year’s reading list!)

- Pumpkin Soup by Helen Cooper

- Moomin and the Golden Leaf by Richard Dungworth

- Little Owl’s Orange Scarf by Tatyana Feeney

- Christopher Pumpkin by Sue Hendra and Paul Linnet

- The Steves by Morag Hood

- Sloth Slept On by Frann Preston-Gannon

- Think of an Eel by Karen Wallace

SKIMMED

- 33 Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong End of Medicine by David Jarrett

- A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride

- The Glorious Heresies by Lisa McInerney

- The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

CURRENTLY READING

- The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier (for book club)

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Just Like You by Nick Hornby

- Vesper Flights: New and Selected Essays by Helen Macdonald

- The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

- First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger

- Real Life by Brandon Taylor

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- The Book of Gutsy Women by Chelsea Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton

- What Have I Done? An Honest Memoir about Surviving Postnatal Mental Illness by Laura Dockrill

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Dependency by Tove Ditlevsen

- House of Glass: The Story and Secrets of a Twentieth-Century Jewish Family by Hadley Freeman

- A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth by Daniel Mason

- Something Special by Iris Murdoch

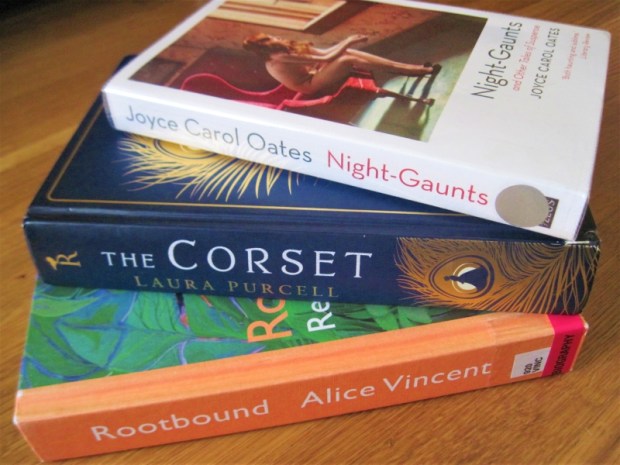

- Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent

+ A few more picture books

+ This exciting university library book haul!

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney

- Dear Reader: The Comfort and Joy of Books by Cathy Rentzenbrink

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson

- The Courage to Care: A Call for Compassion by Christie Watson

And from the university library, for Novellas in November:

- Travels in the Scriptorium by Paul Auster

- Kill My Mother: A Graphic Novel by Jules Feiffer

- The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Mr Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

- Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

- Tilly and the Map of Stories (Pages & Co. #3) by Anna James

- Kay’s Anatomy: A Complete (and Completely Disgusting) Guide to the Human Body by Adam Kay

- The Dickens Boy by Thomas Keneally

- To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss

- Mantel Pieces: Royal Bodies and Other Writing from the London Review of Books by Hilary Mantel

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- My Last Supper: One Meal, a Lifetime in the Making by Jay Rayner

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense by Joyce Carol Oates – I read and reviewed the first story for R.I.P. but didn’t continue.

- The Corset by Laura Purcell – My second DNF of a Purcell after last year and The Silent Companions. Her setups are appealing but she just doesn’t deliver the excitement. I made it to page 41. Really I should give up on her, but Bone China is still on my TBR…

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Magic Toyshop by Angela Carter – I decided it didn’t quite fit the bill for R.I.P. I will try it another time, though.

What appeals from my stacks?

Nonfiction Catch-Up: Long-Term Thinking, Finding a Home in Wales, Eels

Not long now until Nonfiction November. I’m highlighting three nonfiction books I’ve read over the last few months; any of them would be well worth your time if you’re still looking for some new books to add to the pile. I’ve got a practical introduction to the philosophy and politics of long-term/intergenerational planning, a group biography about the two gay couples who inhabited a house in the Welsh hills in turn, and a wide-ranging work on eels.

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric

I saw Krznaric introduce this via a digital Hay Festival session back in May. He is an excellent speaker and did an admirable job of conveying all the major ideas from his recent work within a half-hour presentation. Unfortunately, this meant that reading the book itself didn’t add much for me, although it goes deeper into his propositions and is illustrated with unique, helpful figures.

I saw Krznaric introduce this via a digital Hay Festival session back in May. He is an excellent speaker and did an admirable job of conveying all the major ideas from his recent work within a half-hour presentation. Unfortunately, this meant that reading the book itself didn’t add much for me, although it goes deeper into his propositions and is illustrated with unique, helpful figures.

Without repeating from my write-up of the Festival talk, then, I’ll add in points and quotes that struck me:

- “some of the fundamental ways we organise society, from nation states and representative democracy to consumer culture and capitalism itself, are no longer appropriate for the age we live in.”

- 100 years as the minimum timeframe to think about (i.e., a long human life) – “taking us beyond the ego boundary of our own mortality so we begin to imagine futures that we can influence yet not participate in ourselves.”

- “The phones in our pockets have become the new factory clocks, capturing time that was once our own and offering in exchange a continuous electronic now full of infotainment, advertising and fake news. The distraction industry works by cleverly tapping into our ancient mammalian brains: our ears prick up at the ping of an arriving message … Facebook is Pavlov, and we’re the dogs.”

- The Intergenerational Solidarity Index as a way of assessing governments’ future preparation: long-term democracies tend to perform better, though they aren’t perfect; Iceland scores the highest of all, followed by Sweden.

- Further discussion of Doughnut Economics (a model developed by Krznaric’s wife, Kate Raworth), which pictures the sweet spot humans need to live in between a social foundation and the ecological ceiling; failures lead to overshoot or shortfall.

- Four fundamental barriers to change: outdated institutional designs (our basic political systems), the power of vested interests (fossil fuel companies, Amazon, et al.), current insecurity (refugees), and “insufficient sense of crisis” – we’re like frogs in a gradually boiling pot, he says, and need to be jolted out of our complacency.

This is geared more towards economics and politics than much of what I usually read, yet fits in well with other radical visions of the future I’ve engaged with this year (some of them more environmentalist in approach), including Footprints by David Farrier, The Future Earth by Eric Holthaus, and Notes from an Apocalypse by Mark O’Connell.

With thanks to WH Allen for the free copy for review.

On the Red Hill: Where Four Lives Fell into Place by Mike Parker (2019)

I ordered a copy from Blackwell’s after this made it through to the Wainwright Prize shortlist – it went on to be named the runner-up in the UK nature writing category. It’s primarily a memoir/group biography about Parker, his partner Peredur, and George and Reg, the couple who previously inhabited their home of Rhiw Goch in the Welsh Hills and left it to the younger pair in their wills. In structuring the book into four parts, each associated with an element, a season, a direction of the compass and a main character, Parker focuses on the rhythms of the natural year. The subtitle emphasizes the role Rhiw Goch played, providing all four with a sense of belonging in a rural setting not traditionally welcoming to homosexuals.

I ordered a copy from Blackwell’s after this made it through to the Wainwright Prize shortlist – it went on to be named the runner-up in the UK nature writing category. It’s primarily a memoir/group biography about Parker, his partner Peredur, and George and Reg, the couple who previously inhabited their home of Rhiw Goch in the Welsh Hills and left it to the younger pair in their wills. In structuring the book into four parts, each associated with an element, a season, a direction of the compass and a main character, Parker focuses on the rhythms of the natural year. The subtitle emphasizes the role Rhiw Goch played, providing all four with a sense of belonging in a rural setting not traditionally welcoming to homosexuals.

Were George and Reg the ‘only gays in the village,’ as the Little Britain sketch has it? Impossible to say, but when they had Powys’ first same-sex civil partnership ceremony in February 2006, they’d been together nearly 60 years. By the time Parker and his partner took over the former guesthouse, gay partnerships were more accepted. In delving back into his friends’ past, then, he conjures up another time: George fought in the Second World War, and for the first 18 years he was with Reg their relationship was technically illegal. But they never rubbed it in any faces, preferring to live quietly, traveling on the Continent and hosting guests at their series of Welsh B&Bs; their politics was conservative, and they were admired locally for their cooking and hospitality (Reg) and endurance cycling (George).

There are lots of in-text black-and-white photographs of Reg and George over the years and of Rhiw Goch through the seasons. Using captioned photos, journal entries, letters and other documents, Parker gives a clear impression of his late friends’ characters. There is something pitiable about both: George resisting ageing with nude weightlifting well into his sixties; Reg still essentially ashamed of his sexuality as well as his dyslexia. I felt I got to know the younger protagonists less well, but that may simply be because their stories are ongoing. It’s remarkable how Welsh Parker now seems: though he grew up in the English Midlands, he now speaks decent Welsh and has even stood for election for the Plaid Cymru party.

It’s rare to come across something in the life writing field that feels genuinely sui generis. There were moments when my attention waned (e.g., George’s feuds with the neighbors), but so strong is the overall sense of time, place and personality that this is a book to prize.

The Gospel of the Eels: A Father, a Son and the World’s Most Enigmatic Fish by Patrik Svensson

[Translated from the Swedish by Agnes Broomé]

“When it comes to eels, an otherwise knowledgeable humanity has always been forced to rely on faith to some extent.”

We know the basic facts of the European eel’s life cycle: born in the Sargasso Sea, it starts off as a larva and then passes through three stages that are almost like separate identities: glass eel, yellow eel, silver eel. After decades underwater, it makes its way back to the Sargasso to spawn and die. Yet so much about the eel remains a mystery: why the Sargasso? What do the creatures do for all the time in between? Eel reproduction still has not been observed, despite scientists’ best efforts. Among the famous names who have researched eels are Aristotle, Sigmund Freud and Rachel Carson, all of whom Svensson discusses at some length. He even suggests that, for Freud, the eel was a suitable early metaphor for the unconscious – “an initial insight into how deeply some truths are hidden.”

We know the basic facts of the European eel’s life cycle: born in the Sargasso Sea, it starts off as a larva and then passes through three stages that are almost like separate identities: glass eel, yellow eel, silver eel. After decades underwater, it makes its way back to the Sargasso to spawn and die. Yet so much about the eel remains a mystery: why the Sargasso? What do the creatures do for all the time in between? Eel reproduction still has not been observed, despite scientists’ best efforts. Among the famous names who have researched eels are Aristotle, Sigmund Freud and Rachel Carson, all of whom Svensson discusses at some length. He even suggests that, for Freud, the eel was a suitable early metaphor for the unconscious – “an initial insight into how deeply some truths are hidden.”

But there is a more personal reason for Svensson’s fascination with eels. As a boy he joined his father in eel fishing on Swedish summer nights. It was their only shared hobby; the only thing they ever talked about. His father was as much a mystery to him as eels are to science. And it was only as his father was dying of a cancer caused by his long road-paving career that Svensson came to understand secrets he’d kept hidden for decades.

Chapters alternate between this family story and the story of the eels. The book explores eels’ place in culture (e.g., Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum) and their critically endangered status due to factors such as a herpes virus, nematode infection, pollution, overfishing and climate change. A prior curiosity about marine life would be helpful to keep you going through this, but the prose is lovely enough to draw in even those with a milder interest in nature writing.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

One of my recent borrows from the public library’s children’s section was the picture book Think of an Eel by Karen Wallace. Her unrhymed, alliterative poetry and the paintings by Mike Bostock beautifully illustrate the eel’s life cycle and journey.

You simply must hear folk singer Kitty Macfarlane’s gorgeous song “Glass Eel” – literally about eels, it’s also concerned with migration, borders and mystery.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes

Stephen Fabes is an emergency room doctor at St Thomas’s Hospital, London. Not exciting enough for you? Well, he also spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents (so, all bar Antarctica). His statistics are beyond impressive: 53,568 miles, 102 international borders, 1000+ nights of free camping, 26 bicycle tires, and 23 journals filled with his experiences. A warm-up was cycling the length of Chile with his brother at age 19. After medical school in Liverpool and starting his career in London, he found himself restless and again longing for adventure. The round-the-world cycle he planned fell into four sections: London to Cape Town, the West Coast of the Americas, Melbourne to Mumbai, and Hong Kong to home.

Signs of Life is a warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of Fabes’ travels, achieving a spot-on balance between major world events, the everyday discomforts of long-distance cycling and rough camping, and his humanitarian volunteering. He is a witness to the Occupy movement in Hong Kong, the aftermath of drought and tribal conflict in Africa, and the refugee crisis via the “Jungle” migrant camp in Calais. The desperate situations he saw while putting his medical expertise to good use in short bursts – e.g., at a floating clinic on a Cambodian lake, a malaria research center in Thailand, a leper hospital in Nepal, and a mental health rehabilitation clinic in Mumbai – put into perspective more minor annoyances like fire ants in El Salvador, Indonesian traffic, extreme cold in Mongolia, and camel spiders.

Wherever he went, Fabes met with kindness from strangers, even those who started off seeming hostile – having pitched his tent by a derelict cabin in Peru, he was alarmed to awake to a man pointing a gun at him, but the illicit gold miner soon determined he was harmless and offered him some soup. (Police officers and border guards were perhaps a bit less hospitable.) He also had occasional companions along the route, including a former housemate and a one-time girlfriend. Even limited shared language was enough to form common ground with a stranger-turned-fellow cyclist for a week or so. We get surprising glimpses of how Anglo-American culture permeates the developing world: For some reason, in the ‒Stans everyone’s point of reference when he introduced himself was Steven Seagal.

At nearly 400 pages, the memoir is on the long side, though I can see that it must have felt impossible to condense six years of adventures any further. I was less interested in the potted histories of other famous cyclists’ travels and would have appreciated a clearer sense to the passing of time, perhaps in the form of a date stamp at the head of each chapter. One of my favorite aspects of the book, though, was the use of medical metaphors to link geography to his experiences. Most chapters are titled after health vocabulary; for instance, in “Membranes” he ponders whether country borders are more like scars or cell membranes.

Fabes emphasizes, in a final chapter on the state of the West upon his return in early 2016, that, in all the most important ways, people are the same the world over. Whether in the UK or Southeast Asia, he sees poverty as the major factor in illness, perpetuating the inequality of access to adequate healthcare. Curiosity and empathy are his guides as he approaches each patient’s health as a story. Reflecting on the pandemic, which hit just as he was finalizing the manuscript, he prescribes global cooperation and innovation for this time of uncertainty.

We’re all armchair travelers this year, but this book is especially for you if you enjoy Bill Bryson’s sense of humor, think Dervla Murphy was a badass in Full Tilt, and enjoyed War Doctor by David Nott and/or The Crossway by Guy Stagg. It’s one of my top few predictions for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize – fingers crossed it will go ahead after the 2020 hiatus.

My rating:

With thanks to Dr Fabes and Profile Books for the free copy for review.

Autumn Reading: The Pumpkin Eater and More

I’ve been gearing up for Novellas in November with a few short autumnal reads, as well as some picture books bedecked with fallen leaves, pumpkins and warm scarves.

An Event in Autumn by Henning Mankell (2004)

[Translated from the Swedish by Laurie Thompson, 2014]

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

Of course things aren’t going to go smoothly with this venture. You have to suspend disbelief when reading about the adventures of investigators; it’s like they attract corpses. So it’s not much of a surprise that while he’s walking the grounds of this house he finds a human hand poking out of the soil, and eventually the remains of a middle-aged couple are unearthed. The rest of the book is about finding out what happened on the property at the time of the Second World War. Wallander says he doesn’t believe in ghosts, but victims of wrongful death are as persistent as ghosts: they won’t be ignored until answers are found.

This was a quick and easy read, but nothing about it (setting, topics, characterization, prose) made me inclined to read further in the author’s work.

My rating:

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer (1962)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, they’re building a glass tower as their countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood.

An excellent 2011 introduction by Daphne Merkin reveals how autobiographical this seventh novel was for Mortimer. But her backstory isn’t a necessary prerequisite for appreciating this razor-sharp period piece. You get a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility and chafing at the thought that she’s had no choice in what life has dealt her. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humor and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind. I was reminded of Janice Galloway’s The Trick Is to Keep Breathing and Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. If you’re still looking for ideas for Novellas in November, I recommend it highly.

My rating:

Snow in Autumn by Irène Némirovsky (1931)

[Translated from the French by Sandra Smith, 2007]

(Classic of the Month, #2)

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

My rating:

Plus a quartet of children’s picture books from the library:

Pumpkin Soup by Helen Cooper: A cat, a squirrel and a duck live together in a teapot-shaped cabin in the woods. They cook pumpkin soup and make music in perfect harmony, each cheerfully playing their assigned role, until the day Duck decides he wants to be the one to stir the soup. A vicious quarrel ensues, and Duck leaves. Nothing is the same without the whole trio there. After some misadventures, when the gang is finally back together, they’ve learned their lesson about flexibility … or have they? Adorably mischievous.

Moomin and the Golden Leaf by Richard Dungworth: Beware: this is not actually a Tove Jansson plot, although her name is, misleadingly, printed on the cover (under tiny letters “Based on the original stories by…”). Autumn has come to Moominvalley. Moomin and Sniff find a golden leaf while they’re out foraging. He sets out to find the golden tree it must have come from, but the source is not what he expected. Meanwhile, the rest are rehearsing a play to perform at the Autumn Ball before a seasonal feast. This was rather twee and didn’t capture Jansson’s playful, slightly melancholy charm.

Little Owl’s Orange Scarf by Tatyana Feeney: Ungrateful Little Owl thinks the orange scarf his mother knit for him is too scratchy. He tries “very hard to lose his new scarf” and finally manages it on a trip to the zoo. His mother lets him choose his replacement wool, a soft green. I liked the color blocks and the simple design, and the final reveal of what happened to the orange scarf is cute, but I’m not sure the message is one to support (pickiness vs. making do with what you have).

Christopher Pumpkin by Sue Hendra and Paul Linnet: The witch of Spooksville needs help preparing for a big party, so brings a set of pumpkins to life. Something goes a bit wrong with the last one, though: instead of all things ghoulish, Christopher Pumpkin loves all things fun. He bakes cupcakes instead of stirring gross potions and strums a blue ukulele instead of inducing screams. The witch threatens to turn Chris into soup if he can’t be scary. The plan he comes up with is the icing on the cake of a sweet, funny book delivered in rhyming couplets. Good for helping kids think about stereotypes and how we treat those who don’t fit in.

Have you read any autumn-appropriate books lately?

Announcing Novellas in November!

Lots of us make a habit of prioritizing novellas in our November reading. (Who can resist that alliteration?) Perhaps you’ve been finding it hard to focus on books with all the bad news around, and your reading target for the year is looking out of reach. If you’re beset by distractions or only have brief bits of free time in your day, short books can be a boon.

In 2018 Laura Frey surveyed the history of Novellas in November, which has had various incarnations but no particular host. This year Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting it as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts. We’ll both put up an opening post on 1 November where you can leave your links throughout the month, to be rounded up on the 30th, and we’ll take turns introducing a theme each Monday.

The definition of a novella is loose – it’s based on word count rather than number of pages – but we suggest aiming for 150 pages or under, with a firm upper limit of 200 pages. Any genre is valid. As author Joe Hill (the son of Stephen King) has said, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” With distinctive characters, intense scenes and sharp storytelling, the best novellas can draw you in for a memorable reading experience – maybe even in one sitting.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Australia Reading Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that count towards multiple challenges? See Cathy’s recent post for ideas of how books can overlap on a few categories. Or you might choose a short Atwood novel, like Surfacing (186 pages) or The Penelopiad (199 pages).

2–8 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas (Rebecca)

16–22 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

23–29 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

We’re looking forward to having you join us! Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and the hashtag #NovNov.

My stacks of possibilities for the four weeks (with a library haul of mostly lit in translation to follow).

Bonus points for three of the below being November review books!

Another Birthday & An “Overhaul” of Previous Years’ Gifted Books

I thought a Wednesday would be a crummy day to have a birthday on, but actually it was great – the celebrations have extended from the weekend before to the weekend after, giving me a whole week of treats. Last Saturday we planned a last-minute trip to Oxford when I won a pair of free tickets to the Oxford Playhouse’s comedy club, their first live event since March. It featured three acts plus a compere and was headlined by Flo & Joan, a musical sister act we’d seen before at Greenbelt 2018. Beforehand, we had excellent pizzas at Franco Manca. Oxford felt busy, but we wore masks to queue at the restaurant and for the whole time in the Playhouse, where there were several seats left between parties plus every other row was empty.

My husband was able to work from home on the day itself, even though he’s been having a manically busy couple of weeks of in-person teaching and labs on campus, so we got to share a few meals: a leisurely pancake breakfast; fresh-baked maple, walnut and pear upside-down cake, a David Lebovitz recipe from Ready for Dessert (recreated here); and a French-influenced dinner at The Blackbird, a local pub we’d not tried before. In between I did some reading (of course), helped hunt in the garden for invertebrates for the labs, and did a video chat with my mom and sister in the States.

Today, since he had a bit more time free, he has made me Mexican food, one of my favorite cuisines and something I don’t get to have very often, plus a second cake from a Lebovitz recipe (luckily, the remnants of the last one had already gone in the freezer), this time a flourless chocolate cake topped with cacao nibs.

Just three books came in as gifts this year, though I might buy a few more with birthday money and vouchers. (A proof copy of Claire Fuller’s new novel, forthcoming in January, happened to arrive on my birthday, so I’ll call that four books as presents!) I also received chocolate, posh local drink, and the latest Alanis album.

An Overhaul of Previous Years’ Gifted Books

For a bit of fun, I thought I’d go back through the previous birthday book hauls I’ve posted about and see how many of the books I’ve read: 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019.

Simon of Stuck in a Book runs a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With permission, I’ve borrowed the title and format.

Date of haul: October 2015

Number of books purchased: 7 [the bottom 3 pictured were bought for other people]

Had already read: 2 (the Byatt story collections, one of which I reread earlier this year)

Read since: 2 (reviews of the Jerome and Zola appeared on the blog)

Still to read: 3 – It’s high time I got around to the Byron and Dinesen books after five years sat on my shelves! I DNFed the first Gormenghast book, though, so may end up jettisoning the whole trilogy.

Date of haul: October 2016

Number of books purchased/received: 6

Read: ALL 6! I am so proud about this. Reviews of the Brown, Taylor, and Welch have appeared on the blog.

Still own: Just 2 – I resold the Brown and Holloway after reading them, gave the Mercer to a friend, and donated the Taylor proof.

Date of haul: October 2017

Number of books received: 11

Read: 4 (reviews of the Cox, Hay, and Hoffman appeared on the blog)

DNFed and resold: 2

Still to read: 5

Date of haul: October 2018

Number of books received: 10

Read: 8! Another fine showing; only the Giffels and Winner remain to be read. Reviews of the Groff, one L’Engle, and Manyika & Richardson appeared on the blog.

Still own: 8 – I resold the Hood and Petit after reading them.

Date of haul: October 2019

Number of books received: 14

Read: Only 2. Hmm. (I reviewed the Weiss, and the Houston appeared on my Best of 2019 runners-up list.)

Currently reading/skimming, or set aside temporarily: 4

DNFed and resold: 3. D’oh.

Still to read: 5

Are you good about reading gifted books quickly?

What catches your eye from my stacks?

The 1956 Club: The Lonely Londoners and Night

It’s my second time participating in one of Simon and Karen’s reading weeks (after the 1920 Club earlier this year). It was a boon that the two books I chose and borrowed from the library were of novella length. As in April, I managed one very enjoyable read and one slightly less successful skim.

The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon

This title was familiar to me because it was one of the texts the London secondary school students could choose to review for a special supplement of Wasafiri literary magazine when I did a few in-school sessions mentoring them in the basics of book reviewing in early 2014. (An experience that was totally outside my comfort zone and now feels like a lifetime away.)

Selvon, a Trinidadian journalist who settled in London in 1950, became known as the “father of black writing” in Britain. Moses Aloetta, an expert in London life after a few years here, lends a hand to his West Indian brethren who are fresh off the boat. As the book opens, he’s off to meet Henry Oliver, whom he soon dubs “Sir Galahad” for his naïve idealism. Moses warns Galahad that, although racism isn’t as blatant as in America, the British certainly aren’t thrilled about black people coming over and taking their jobs. Galahad reassures him that he’s a “born hustler.” We meet a series of other immigrants, like Cap and Bart, who move flats and change jobs frequently, drink and carouse, and “love woman too bad.”

Selvon, a Trinidadian journalist who settled in London in 1950, became known as the “father of black writing” in Britain. Moses Aloetta, an expert in London life after a few years here, lends a hand to his West Indian brethren who are fresh off the boat. As the book opens, he’s off to meet Henry Oliver, whom he soon dubs “Sir Galahad” for his naïve idealism. Moses warns Galahad that, although racism isn’t as blatant as in America, the British certainly aren’t thrilled about black people coming over and taking their jobs. Galahad reassures him that he’s a “born hustler.” We meet a series of other immigrants, like Cap and Bart, who move flats and change jobs frequently, drink and carouse, and “love woman too bad.”

I read and enjoyed the first 52 pages but skimmed from that point on because the patois, while initially captivating, got to be a bit much – I have a limited tolerance for dialect, and for episodic storytelling. I did love the sequences about Galahad catching pigeons for food and Cap following up with seagulls. There is a strong voice and sense of place here: if you want to experience London in the 1950s and see a rarer immigrant perspective, it would be a great choice. (Also recently reviewed by Liz and Annabel.)

Representative passages:

“It have people living in London who don’t know what happening in the room next to them, far more the street, or how other people living. London is a place like that. It divide up in little worlds, and you stay in the world you belong to and you don’t know anything about what happening in the other ones except what you read in the papers.”

the nine-page stream-of-consciousness paragraph that starts “Oh what a time it is when summer come to the city and all them girls throw away heavy winter coat and wearing light summer frocks so you could see the legs and shapes that was hiding away from the cold blasts”

My rating:

Night by Elie Wiesel

[Translated from the French by Marion Wiesel]

A short, harrowing memoir of concentration camp life. Eliezer Wiesel was a young teenager obsessed with the Kabbalah when his family was moved into a Romanian ghetto for Jews and then herded onto a transport train. Uniquely in my reading of Holocaust memoirs, Wiesel was not alone but had his father by his side for much of the time as they were shuttled between various concentration camps including Auschwitz and Buchenwald, from which he was liberated in April 1945. But if the presence of family started as a blessing in a life of privation and despair, it became more of a liability as his father fell ill with dysentery.

Like Viktor Frankl, Wiesel puts his survival down to luck: not once but several times, he and his father were sent to the left (towards the crematoria), but spared at the last minute. They endured infection, a stampede, a snowstorm and near-starvation. But their faith did not survive intact. “For God’s sake, where is God?” someone watching the hanging of a child burst out. “And from within me, I heard a voice answer: ‘Where He is? This is where—hanging here from this gallows.’” I’d heard that story before, twisted by Christian commentators into a “Hey, that’s like Jesus on the cross! God is right here suffering with us” message when actually it’s more “God is dead. God has abandoned us.”

Like Viktor Frankl, Wiesel puts his survival down to luck: not once but several times, he and his father were sent to the left (towards the crematoria), but spared at the last minute. They endured infection, a stampede, a snowstorm and near-starvation. But their faith did not survive intact. “For God’s sake, where is God?” someone watching the hanging of a child burst out. “And from within me, I heard a voice answer: ‘Where He is? This is where—hanging here from this gallows.’” I’d heard that story before, twisted by Christian commentators into a “Hey, that’s like Jesus on the cross! God is right here suffering with us” message when actually it’s more “God is dead. God has abandoned us.”

From the preface to a new translation by his wife, I learned that the original Yiddish manuscript was even bleaker in outlook, with opening and closing passages that voice a cynical loss of trust in God and fellow man. “I am not so naïve as to believe that this slim volume will change the course of history or shake the conscience of the world. Books no longer have the power they once did. Those who kept silent yesterday will remain silent tomorrow” was the chilling final line of his first version. And yet Night has been taught in many high schools, and if it opens even a few students’ eyes – given the recent astonishing statistics about American ignorance of the scope of the Holocaust – it has been of value.

Wiesel won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. His acceptance speech is appended to the text of my 2008 Penguin paperback. In it he declares: “I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must—at that moment—become the center of the universe.” Wise words with perennial relevance.

My rating:

Wigtown Book Festival 2020: The Bookshop Band, Bythell, O’Connell & Stuart

During the coronavirus pandemic, we have had to take small pleasures where we can. One of the highlights of lockdown for me has been the chance to participate in literary events like book-themed concerts, prize shortlist announcements, book club discussions, live literary award ceremonies and book festivals that time, distance and cost might otherwise have precluded.

In May I attended several digital Hay Festival events, and this September to early October I’ve been delighted to journey back to Wigtown, Scotland – even if only virtually.

The Bookshop Band

The Bookshop Band have been a constant for me this year. After watching their 21 Friday evening lockdown shows on Facebook, as well as a couple of one-off performances for other festivals, I have spent so much time with them in their living room that they feel more like family than a favorite band. Add to that four of the daily breakfast chat shows from the Wigtown Book Festival and I’ve seen them play over 25 times this year already!

(The still below shows them with, clockwise from bottom left, guests Emma Hooper, Stephen Rutt and Jason Webster.)

Ben and Beth’s conversations with featured authors and local movers and shakers, punctuated by one song per guest, were pleasant to have on in the background while working. The songs they performed were, ideally, written for those authors’ books, but other times just what seemed most relevant; at times this was a stretch! I especially liked seeing Donal Ryan, about whose The Spinning Heart they’ve recently written a terrific song; Kate Mosse, who has been unable to write during lockdown so (re)read 200 books instead, including all of Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh et al.; and Ned Beauman, who is nearing the deadline for his next novel, a near-future story of two scientists looking for traces of the venomous lumpsucker (a made-up fish) in the Baltic Sea. Closer to science fiction than his previous work, it’s a funny take on extinctions, he said. I’ve read all of his published work, so I’m looking forward to this one.

Shaun Bythell

The opening event of the Festival was an in-person chat between Lee Randall and Shaun Bythell in Wigtown, rather than the split-screen virtual meet-ups that made up the rest of my viewing. Bythell, owner of The Book Shop, has become Wigtown’s literary celebrity through The Diary of a Bookseller and its sequel. In early November he has a new book coming out, Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops. I’m halfway through it and it has more substance than its stocking-stuffer dimensions would imply. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names, as if he’s naming species.

The opening event of the Festival was an in-person chat between Lee Randall and Shaun Bythell in Wigtown, rather than the split-screen virtual meet-ups that made up the rest of my viewing. Bythell, owner of The Book Shop, has become Wigtown’s literary celebrity through The Diary of a Bookseller and its sequel. In early November he has a new book coming out, Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops. I’m halfway through it and it has more substance than its stocking-stuffer dimensions would imply. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names, as if he’s naming species.

The Book Shop closed for 116 days during COVID-19: the only time in more than 40 years that it has been closed for longer than just over the Christmas holidays. He said that it has been so nice to see customers again; they’ve been a ray of sunshine for him, something the curmudgeon would never usually say! Business has been booming since his reopening, with Agatha Christie his best seller – it’s not just Mosse who’s turning to cozy mysteries. He’s also been touched by the kindness of strangers, such as one from Monaco who sent him £300, having read an article by Margaret Atwood about how hard it is for small businesses just now and hoping it would help the shop survive until they could get there in person.

(Below: Bythell on his 50th birthday, with Captain the cat.)

Randall and Bythell discussed a few of the types of customers he regularly encounters. One is the autodidact, who knows more than you and intends for you to know it. This is not the same, though, as the expert who actually helps you by sharing their knowledge (of a rare cover version on an ordinary-looking crime paperback, for instance). There’s also the occultists, the erotica browsers, the local historians and the young families – now that he has one of his own, he’s become a bit more tolerant.

Mark O’Connell

Appearing from Dublin, Mark O’Connell was interviewed by Scottish writer and critic Stuart Kelly about his latest book, Notes from an Apocalypse (my review). He noted that, while all authors hope their books are timely, perhaps he overshot with this one! The book opens with climate change as the most immediate threat, yet now he feels that “has receded as the locus of anxiety.” O’Connell described the “flattened” experience of being alive at the moment and contrasted it with the existential awfulness of his research travels. For instance, he read a passage from the book about being at an airport Yo Sushi! chain and having a vision of horror at the rampant consumerism its conveyor belt seemed to represent.

Appearing from Dublin, Mark O’Connell was interviewed by Scottish writer and critic Stuart Kelly about his latest book, Notes from an Apocalypse (my review). He noted that, while all authors hope their books are timely, perhaps he overshot with this one! The book opens with climate change as the most immediate threat, yet now he feels that “has receded as the locus of anxiety.” O’Connell described the “flattened” experience of being alive at the moment and contrasted it with the existential awfulness of his research travels. For instance, he read a passage from the book about being at an airport Yo Sushi! chain and having a vision of horror at the rampant consumerism its conveyor belt seemed to represent.

Kelly characterized O’Connell’s personal, self-conscious approach to the end of the world as “brave,” while O’Connell said, “in terms of mental health, I should have chosen any other topic!” Having children creates both vulnerability and possibility, he contended, and “it doesn’t do you any good as a parent to indulge in those predilections [towards extreme pessimism].” They discussed preppers’ white male privilege, New Zealand and Mars as havens, and Greta Thunberg and David Attenborough as saints of the climate crisis.

O’Connell pinpointed Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax as the work he spends more time on in his book than any other; none of your classic nihilist literature here, and he deliberately avoided bringing up biblical references in his secular approach. In terms of the author he’s reached for most over the last few years, and especially during lockdown, it’s got to be Annie Dillard. Speaking of the human species, he opined, “it should not be unimaginable that we should cease to exist at some point.”

This talk didn’t add much to my experience of reading the book (vice versa would probably be true, too – I got the gist of Roman Krznaric’s recent thinking from his Hay Festival talk and so haven’t been engaging with his book as much as I’d like), but it was nice to see O’Connell ‘in person’ since he couldn’t make it to the 2018 Wellcome Book Prize ceremony.

Douglas Stuart

Glasgow-born Douglas Stuart is a fashion designer in New York City. Again the interviewer was Lee Randall, an American journalist based in Edinburgh – she joked that she and Stuart have swapped places. Stuart said he started writing his Booker-shortlisted novel, Shuggie Bain, 12 years ago, and kept it private for much of that time. Although he and Randall seemed keen to downplay how autobiographical the work is, like his title character, Stuart grew up in 1980s Glasgow with an alcoholic single mother. As a gay boy, he felt he didn’t have a voice in Thatcher’s Britain. He knew many strong women who were looked down on for being poor.

It’s impossible to write an apolitical book about poverty (or a Glasgow book without dialect), Stuart acknowledged, yet he insisted that the novel is primarily “a portrait of two souls moving through the world,” a love story about Shuggie and his mother, Agnes. The author read a passage from the start of Chapter 2, when readers first meet Agnes, the heart of the book. Randall asked about sex as currency and postulated that all Agnes – or any of these characters; or any of us, really – wants is someone whose face lights up when they see you.

It’s impossible to write an apolitical book about poverty (or a Glasgow book without dialect), Stuart acknowledged, yet he insisted that the novel is primarily “a portrait of two souls moving through the world,” a love story about Shuggie and his mother, Agnes. The author read a passage from the start of Chapter 2, when readers first meet Agnes, the heart of the book. Randall asked about sex as currency and postulated that all Agnes – or any of these characters; or any of us, really – wants is someone whose face lights up when they see you.

The name “Shuggie” was borrowed from a small-town criminal in his housing scheme; it struck him as ironic that a thug had such a sweet nickname. Stuart said that writing the book was healing for him. He thinks that men who drink and can’t escape poverty are often seen as loveable rogues, while women are condemned for how they fail their children. Through Agnes, he wanted to add some nuance to that double standard.

The draft of Shuggie Bain was 900 pages, single-spaced, but his editor helped him cut it while simultaneously drawing out the important backstories of Agnes and some other characters. He had almost finished his second novel by the time Shuggie was published, so he hopes it will be with readers soon.

[I have reluctantly DNFed Shuggie Bain at p. 100, but I’ll keep my proof copy on the shelf in case one day I feel like trying it again – especially if, as seems likely, it wins the Booker Prize.]

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack.

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack. I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university.

I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university. Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year.

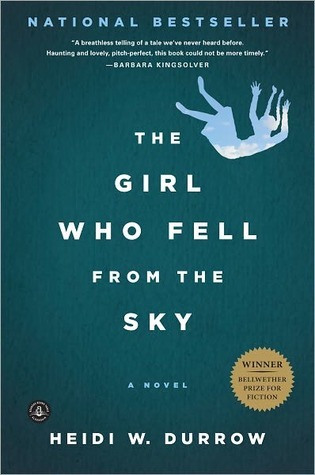

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year. This review is ALL SPOILER because there isn’t really a way to discuss the book otherwise, so skip onwards if you think you might want to read this someday. Durrow was inspired by her own family history – she is biracial, her father a Black serviceman and her mother from Denmark – and by a newspaper story about a woman who jumped off the top of a multi-story building with her small children. Only one daughter survived the fall. Durrow was captivated by that girl’s story and wanted to imagine what her life would be like in the wake of tragedy.

This review is ALL SPOILER because there isn’t really a way to discuss the book otherwise, so skip onwards if you think you might want to read this someday. Durrow was inspired by her own family history – she is biracial, her father a Black serviceman and her mother from Denmark – and by a newspaper story about a woman who jumped off the top of a multi-story building with her small children. Only one daughter survived the fall. Durrow was captivated by that girl’s story and wanted to imagine what her life would be like in the wake of tragedy.

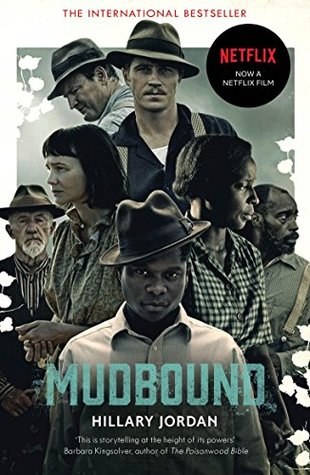

1946: Two servicemen return from fighting in Europe, headed to the same Mississippi farm. Jamie McAllan was a fighter pilot and Ronsel Jackson was part of a tank division. Both are dependent on alcohol to help them cope with the memories of what they have seen and done. But Jamie can get away with drunk driving and carousing with local women, knowing that his big brother, Henry, will take him back in no matter what. Ronsel, though, has to keep his head down and be on his guard at every moment: war hero or not, no one in Mississippi is going to let a Black man walk in through the front door of a store or get a lift home in a white man’s truck. His sharecropping family’s position at the McAllan farm, Mudbound, is precarious, with the weather and the social hierarchy always working against them.

1946: Two servicemen return from fighting in Europe, headed to the same Mississippi farm. Jamie McAllan was a fighter pilot and Ronsel Jackson was part of a tank division. Both are dependent on alcohol to help them cope with the memories of what they have seen and done. But Jamie can get away with drunk driving and carousing with local women, knowing that his big brother, Henry, will take him back in no matter what. Ronsel, though, has to keep his head down and be on his guard at every moment: war hero or not, no one in Mississippi is going to let a Black man walk in through the front door of a store or get a lift home in a white man’s truck. His sharecropping family’s position at the McAllan farm, Mudbound, is precarious, with the weather and the social hierarchy always working against them. 2019 Katherine Seligman, If You Knew [retitled At the Edge of the Haight – publication forthcoming in January 2021]

2019 Katherine Seligman, If You Knew [retitled At the Edge of the Haight – publication forthcoming in January 2021]