#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

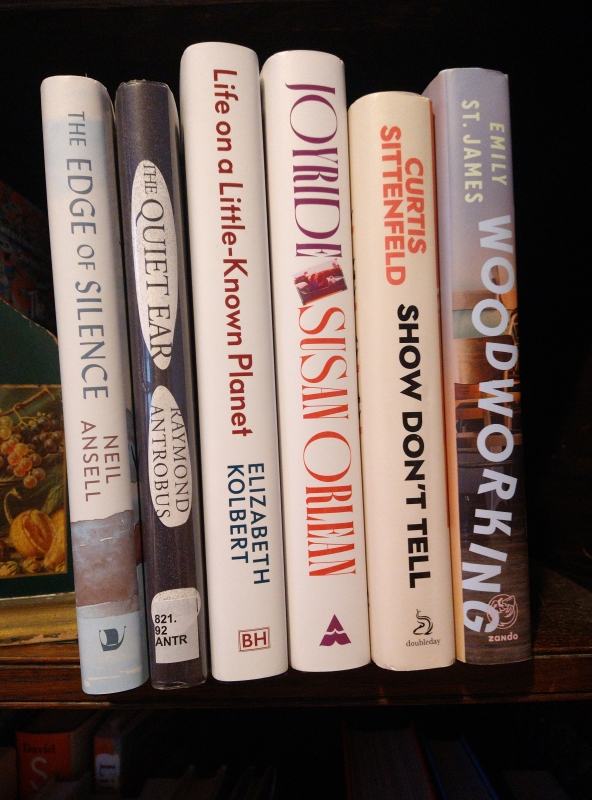

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

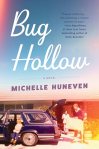

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

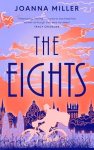

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Guest Review of Greene Ferne Farm by Richard Jefferies (#NovNov25)

As busy as he is as a lecturer in animal ecology at the University of Reading (and a multi-instrumentalist in several folk/Americana bands), my husband, Dr Chris Foster, managed to find time to read and review (below) something for Novellas in November. This is a random, obscure Victorian novel (from 1880) that we picked up at a book sale in Kingsclere last month.

“The 19th-century author Richard Jefferies is better remembered as a nature writer than as a novelist, and in this slight early novella (albeit published only seven years before his death from tuberculosis at age 38) it is indeed his evocation of the landscapes, wildlife and weather of rural Wiltshire that stand out most.

“Jefferies conjures atmosphere skilfully, from an uneasy night lost on chalk downland in thick fog to the lonely, dust-filled room where an avaricious old farmer looks out at the sunset from his armchair. There’s a sense of abundant nature as a backdrop for rural life that can be taken for granted, a sense of connectivity across generations – “the cuckoo came and went; the swallows sailed for the golden sands of the south; the leaves, brown and orange and crimson, dropped and died” – but also a prescient fear expressed here by a landowning squire that modern farming methods such as ‘ploughing engines’ might “suck every atom out of the soil.” The abundance of corncrakes portrayed around Greene Ferne is just one reminder for contemporary readers of how much wildlife has been lost from farmland since Jefferies was writing.

“Jefferies conjures atmosphere skilfully, from an uneasy night lost on chalk downland in thick fog to the lonely, dust-filled room where an avaricious old farmer looks out at the sunset from his armchair. There’s a sense of abundant nature as a backdrop for rural life that can be taken for granted, a sense of connectivity across generations – “the cuckoo came and went; the swallows sailed for the golden sands of the south; the leaves, brown and orange and crimson, dropped and died” – but also a prescient fear expressed here by a landowning squire that modern farming methods such as ‘ploughing engines’ might “suck every atom out of the soil.” The abundance of corncrakes portrayed around Greene Ferne is just one reminder for contemporary readers of how much wildlife has been lost from farmland since Jefferies was writing.

“The plot is lacklustre in comparison to the prose: a Hardyesque blend of love triangles and scenes from rural life, with no sense that the occasionally dramatic events portrayed are helping to build any narrative momentum. The portrayals of rustic village folk, complete with thick country accents, feel clichéd and idealised, especially given the decidedly un-Hardyesque happy ending, but the quality of Jefferies’ writing for much of Greene Ferne Farm is at least an encouragement to check out his other, better-known work.” [126 pages] ![]()

Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Three on a Theme: English Gardeners (Bradbury, Laing and Mabey)

These three 2024 releases share a passion for gardening – but not the old-fashioned model of bending nature to one’s will to create aesthetically pleasing landscapes. Instead, the authors are also concerned with sustainability and want to do the right thing in a time of climate crisis (all three mention the 2022 drought, which saw the first 40 °C day being recorded in the UK). They seek to strike a balance between human interference and letting a site go wild, and they are cognizant of the wider political implications of having a plot of land of one’s own. All three were borrowed from the public library. #LoveYourLibrary

One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

Bradbury is Wildlife Editor of BBC Gardeners’ World Magazine and makes television appearances in the UK. She’s owned her suburban Brighton home for four years and has tried to turn its front and back gardens into havens, however small, for wildlife. The book covers April 2022 to June 2023, spotlighting the drought summer. “It’s about a little garden in south Portslade and one terrified, angry gardener.” Month by month, present-tense chapters form not quite a diary, but a record of what she’s planting, pruning, relocating, and so on. There is also a species profile at the end of each chapter, usually of an insect (as in the latest Dave Goulson book) – she’s especially concerned that she’s seeing fewer, yet she’s worried for local birds, trees and hedgehogs, too.

Often, she takes matters into her own hands. She plucks caterpillars from vegetation in the path of strimmers in the park and raises them at home; protects her garden’s robins from predators and provides enough food so they can nest and raise five fledglings; undertakes to figure out where her pond’s amphibians have come from; rescues hedgehogs; and bravely writes to neighbours who have scaffolding up (for roof repairs, etc.) beseeching them to put up swift boxes while they’re at it. Sometimes it works: a pub being refurbished by new owners happily puts up sparrow boxes when she tells them the birds have always nested in crevices in the building. Sometimes it doesn’t; people ignore her letters and she can’t seem to help but take it personally.

For individuals, it’s all too easy to be overtaken by anxiety, helplessness and despair, and Bradbury acknowledges that collective action and solidarity are vital. “I am reminded, once again, that it’s the community that will save these trees, not me. I’m reminded that community is everything.” She bands together with other environmentally minded people to resist a local development, educate the public about hedgehogs through talks, and oppose “Drone Bastard,” who flies drones at seagulls nesting on rooftops (not strictly illegal; disappointingly, their complaint doesn’t get anywhere with the police, RSPB or RSPCA).

Along the way, there are a few insights into the author’s personal life. She lives with her partner Emma and dog Tosca and accesses wild walks even right on the edge of a city in the Downs. Separate visits to her divorced parents are chances for more nature spotting – in Suffolk to see her father, she hears her first curlew and lapwings – but also involve some sadness, as her mother has aphasia and fatigue after a stroke.

Nearly every day of the chronology seems to bring more bad news for nature. “It’s hard, sometimes,” she admits, “trying to enjoy natural, wonderful events, trying to keep the clawing sense of unease at bay”. She is staunch in her fond stance: “I will love it, with all my heart, whatever has managed to remain, whatever is left.” And she models through her own amazingly biodiverse garden the ways we can extend refuge to other creatures if we throw out that pointless notion of ‘tidiness.’ “The UK’s 30 million gardens represent 30 million opportunities to create green spaces that hold on to water and carbon, create shade, grow food and provide habitats for wildlife that might otherwise not survive.” Reading this made me feel less guilty about the feral tangle of buddleia, ragwort, hemp agrimony and bindweed overtaking the parts of our back garden that aren’t given over to meadow, pond and hedge. Every time I venture back there I see tons of insects and spiders, and that’s all that matters.

My main critique is that one year would have been adequate, cutting the book to 250 pages rather than 300 and ensuring less repetition while still being a representative time period. But Bradbury is impressive for her vigilance and resolve. Some might say that she takes herself and life too seriously, but it’s really more that she’s aware of the scale of destruction already experienced and realistic about what we stand to lose. ![]()

The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

I consider Laing one of our most important public thinkers. I saw her introduce the book via the online Edinburgh Book Festival event “In Search of Eden,” in which she appeared on screen and was interviewed by JC Niala. Laing explained that this is not a totally new topic for her as she has been involved in environmental activism and in herbalism. But in 2020, when she and her much older husband bought a house in Suffolk – the first home she has owned after a life of renting – she started restoring its walled garden, which had been created in the 1960s by Mark Rumary. For a year, she watched and waited to see what would happen in the garden, only removing obvious weeds. This coincided with lockdown, so visits to gardens and archives were limited; she focused more on the creation of her own garden and travelling through literature. A two-year diary resulted, in seven notebooks.

Niala observed that the structure of the book, with interludes set in the Suffolk garden, means that the reader has a place to come back to between the deep dives into history. Why make a garden? she asked Laing. Beauty, pleasure, activity: these would be pat answers, Laing insisted. Instead, as with all her books, the reason is the impulse to make complicated structures. Repetitive tasks can be soothing; “the drudgery can be compelling as well.”

Laing spoke of a garden as both refuge and resistance, a mix of wild and cultivated. In this context, Derek Jarman’s Dungeness garden was a “wellspring of inspiration” for her, “a riposte to a toxic atmosphere” of nuclear power and the AIDS crisis (Rumary, like Jarman, was gay). It’s hard to tell where the beach ends and his garden begins, she noted, and she tried to make her garden similarly porous by kicking a hole in the door so frogs could get in. She hopes it will be both vulnerable and robust, a biodiversity hotspot. With Niala, she discussed the idea of a garden as a return to innocence. We have a “tarnished Eden” due to climate change, and we have to do what we can to reverse that.

The event was brilliant – just the level of detail I wanted, with Laing flitting between subjects and issuing amazingly intelligent soundbites. The book, though, seemed like page after page about Milton (Paradise Lost) and Iris Origo or the Italian Renaissance. I liked it best when it stayed personal to her family and garden project. There are incredible lyric passages, but just stringing together floral species’ names – though they’re lovely and almost incantatory – isn’t art; it also shuts out those of us who don’t know plants, who aren’t natural gardeners. I wasn’t about to Google every plant I didn’t know (though I did for a few). Also, I have read a lot about Derek Jarman in particular. So my reaction was admiration rather than full engagement, and I only gave the book a light skim in the end. It is striking, though, how she makes this subject political by drawing in equality of access and the climate crisis. (Shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize and the Wainwright Prize.) ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“A garden is a time capsule, as well as a portal out of time.”

“A garden is a balancing act, which can take the form of collaboration or outright war. This tension between the world as it is and the world as humans desire it to be is at the heart of the climate crisis, and as such the garden can be a place of rehearsal too, of experimenting with this relationship in new and perhaps less harmful ways.”

“the garden had become a counter to chaos on a personal as well as a political level”

“the more sinister legacy of Eden: the fantasy of perpetual abundance”

The Accidental Garden: Gardens, Wilderness and the Space in Between by Richard Mabey

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages.

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages. ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“being Earth’s creatures ourselves, we too have a right to a niche. So in our garden we’ve had more modest ambitions, for ‘parallel development’ you might say, and a sense of neighbourliness with our fellow organisms.”

“We feel embattled at times, and that we should try to make some sort of small refuge, a natural oasis.”

“A garden, with its complex interactions between humans and nature, is often seen as a metaphor for the wider world. But if so, is our plot a microcosm of this troubled arena or a refuge from it?”

You might think I would have been more satisfied by Mabey’s contemplative bent, or Laing’s wealth of literary and historical allusions. It turns out that when it comes to gardening, Bradbury’s practical approach was what I was after. But you may gravitate to any of these, depending on whether you want something for the hands, intellect or memory.

Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

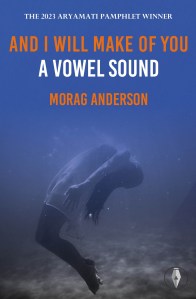

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

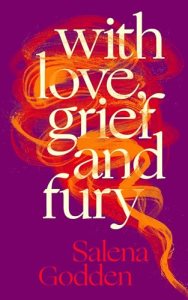

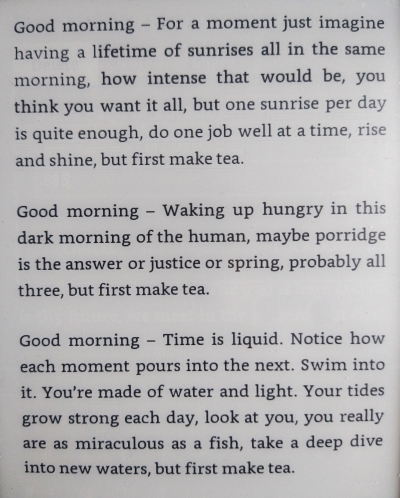

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

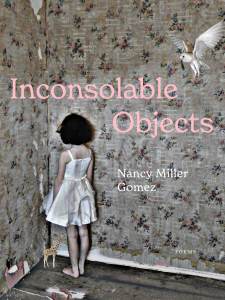

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]