Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

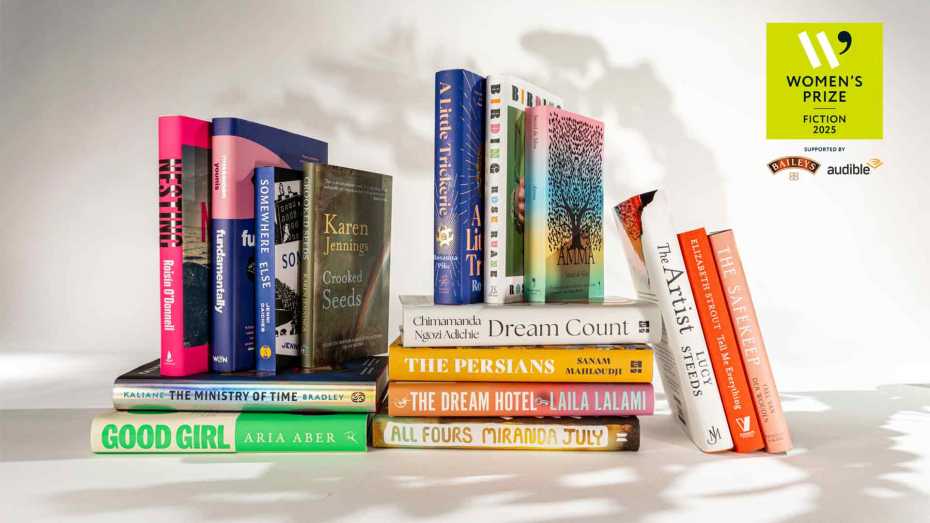

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

My Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Like many bloggers and other book addicts, I’m irresistibly drawn to the new books released each year. However, I consistently find that many memorable reads were published earlier. A few of these are from 2022 or 2023 and most of the rest are post-2000; the oldest is from 1910. These 14 selections (alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order), together with my Best of 2024 post coming up on Tuesday, make up about the top 10% of my year’s reading. Repeated themes included adolescence, parenting (especially motherhood) and trauma. The two not pictured below were read electronically.

Fiction

Fun facts:

- I read 4 of these for book club (Forster, Mandel, Munro and Obreht)

- 3 (Mandel, McEwan and Obreht) were rereads

- I read 2 as part of my Carol Shields Prize shadowing (Foote and Zhang)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Nonfiction

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Carol Shields Prize Reading: Daughter and Dances

Two more Carol Shields Prize nominees today: from the shortlist, the autofiction-esque story of a father and daughter, both writers, and their dysfunctional family; and, from the longlist, a debut novel about the physical and emotional rigours of being a Black ballet dancer.

Daughter by Claudia Dey

Like her protagonist, Mona Dean, Dey is a playwright, but the Canadian author has clearly stated that her third novel is not autofiction, even though it may feel like it. (Fragmentary sections, fluidity between past and present, a lack of speech marks; not to mention that Dey quotes Rachel Cusk and there’s even a character named Sigrid.) Mona’s father, Paul, is a serial adulterer who became famous for his novel Daughter and hasn’t matched that success in the 20 years since. He left Mona and Juliet’s mother, Natasha, for Cherry, with whom he had another daughter, Eva. There have been two more affairs. Every time Mona meets Paul for a meal or a coffee, she’s returned to a childhood sense of helplessness and conflict.

I had a sordid contract with my father. I was obsessed with my childhood. I had never gotten over my childhood. Cherry had been cruel to me as a child, and I wanted to get back at Cherry, and so I guarded my father’s secrets like a stash of weapons, waiting for the moment I could strike.

It took time for me to warm to Dey’s style, which is full of flat, declarative sentences, often overloaded with character names. The phrasing can be simple and repetitive, with overuse of comma splices. At times Mona’s unemotional affect seems to be at odds with the melodrama of what she’s recounting: an abortion, a rape, a stillbirth, etc. I twigged to what Dey was going for here when I realized the two major influences were Hemingway and Shakespeare.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

And then there’s the King Lear setup. (I caught on to this late, perhaps because I was also reading a more overt Lear update at the time, Private Rites by Julia Armfield.) The larger-than-life father; the two older daughters and younger half-sister; the resentment and estrangement. Dey makes the parallel explicit when Mona, musing on her Hemingway-inspired oeuvre, asks, “Why had Shakespeare not called the play King Lear’s Daughters?”

Were it not for this intertextuality, it would be a much less interesting book. And, to be honest, the style was not my favourite. There were some lines that really irked me (“The flowers they were considering were flamboyant to her eye, she wanted less flamboyant flowers”; “Antoine barked. He was barking.”; “Outside, it sunned. Outside, it hailed.”). However, rather like Sally Rooney, Dey has prioritized straightforward readability. I found that I read this quickly, almost as if in a trance, inexorably drawn into this family’s drama. ![]()

Related reads: Monsters by Claire Dederer, The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright, The Wife by Meg Wolitzer, Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Farrar, Straus and Giroux for the free e-copy for review.

Also from the shortlist:

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Longlisted:

Dances by Nicole Cuffy

This was a buddy read with Laura (see her review); I think we both would have liked to see it on the shortlist as, though we’re not dancers ourselves, we’re attracted to the artistry and physicality of ballet. It’s always a privilege to get an inside glimpse of a rarefied world, and to see people at work, especially in a field that requires single-mindedness and self-discipline. Cuffy’s debut novel focuses on 22-year-old Celine Cordell, who becomes the first Black female principal in the New York City Ballet. Cece marvels at the distance between her Brooklyn upbringing – a single mother and drug-dealing older brother, Paul – and her new identity as a celebrity who has brand endorsements and gets stopped on the street for selfies.

Even though Kaz, the director, insists that “Dance has no race,” Cece knows it’s not true. (And Kaz in some ways exaggerates her difference, creating a role for her in a ballet based around Gullah folklore from South Carolina.) Cece has always had to work harder than the others in the company to be accepted:

Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

A further complication is her relationship with Jasper, her white dance partner. It’s an open secret in the company that they’re together, but to the press they remain coy. Cece’s friends Irine and Ryn support her through rocky times, and her former teachers, Luca and Galina, are steadfast in their encouragement. Late on, Cece’s search for Paul, who has been missing for five years, becomes a surprisingly major element. While the sibling bond helps the novel stand out, I most enjoyed the descriptions of dancing. All of the sections and chapters are titled after ballet terms, and even when I was unfamiliar with the vocabulary or the music being referenced, I could at least vaguely picture all the moves in my head. It takes real skill to render other art forms in words. I’ll look forward to following Cuffy’s career. ![]()

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and One World for the free e-copy for review.

Currently reading:

(Shortlist) Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote

(Longlist) Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad

Up next:

(Longlist) You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy

I’m aiming for one more batch of reviews (and a prediction) before the winner is announced on 13 May.

Carol Shields Prize Longlist: A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power

my doll is a collector of tragedy … the device I use to hide from something I already know

Mona Susan Power’s fourth novel, A Council of Dolls, is an Indigenous saga that draws on her own family history. Through first-person narratives by three generations of Dakhóta and Lakhóta women, she explores the ongoing effects of trauma resulting from colonialist oppression. The journey into the past begins with Sissy, a little girl in racist 1960s Chicago with an angry, physically abusive mother, Lillian. This section sets up the book’s pattern of ascribing voice and agency to characters’ dolls. Specifically, Sissy dissociates from her own emotions and upsetting experiences by putting them onto Ethel, her Black doll. Power relies on the dramatic irony between Sissy’s childhood perspective and readers’ understanding.

Moving backward: In 1930s North Dakota, we see Lillian coping with her father’s alcohol-fuelled violence by pretending she is being directed in a play. She loses her Shirley Temple doll, Mae, in an act of charity towards a sickly girl in the community. Lillian and her sister, Blanche, attend an Indian school in Bismarck. Run by nuns, it’s even crueller than the institution their parents, Cora and Jack, attended: the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (also a setting in Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange). Cora’s beautifully introspective journal from the 1910s reveals the systematic cultural annihilation that took place there. Her doll, Winona, rescued from a massacre in the time of Sitting Bull, was on the pyre of precious belongings – tribal costumes, instruments, medals, sacred feathers – burned on students’ arrival. But her stone heart survives as a totem of resilience.

This is a powerful but harrowing story. The characterization and narration are strong, and the nesting-dolls structure means we get glimpses into the future for all three protagonists. However, I was disappointed by a number of Power’s decisions. It appeared that a fourth and final narrator close to the present day would introduce another aspect, but in fact Jesse is a new name that Sissy chose for herself. Now a 50-year-old academic and writer, she becomes a medium for the dolls’ accounts – but this ends up repeating material we’d already encountered. The personification of familial tragedy in the figure of “the injured woman” who appears to Cora verges on mawkish, and the touches of magic realism to do with the dolls sit uneasily beside clinical discussions of trauma. In Jesse’s section, there is something unsubtle about how this forms the basis of a conversation between her and her friend Izzy:

(Jesse thinks) “I wanted that chance to break the chain of passing on harmful inner scripts, the self-loathing that comes from brutally effective colonization.”

(Izzy says) “whoo, that’s a big fat pipe full of misery … Our people have been pathologized from the very beginning. Still are.”

It’s possible I would have responded to this with more enthusiasm had it been packaged as a family memoir. As it is, I was unsure about the hybridization of autofiction and magic realism and wondered what white readers coming to the novel should conclude. I kept in mind Elaine Castillo’s essay “How to Read Now,” about her sense of BIPOC writers’ job: “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. Perhaps Power’s novel was not primarily intended to serve in that way.

I’ll let her have the last word, via the Author’s Note: “outrageously prejudiced depictions of my ancestors and our people are one reason I became a writer. From childhood I felt an urgent need to speak my truth, which was long suppressed. Writing this book was a healing endeavor. May it support the healing of others.”

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Mariner Books for the free e-copy for review.

This was a buddy read with Laura; see her review here.

Before the shortlist is announced on 9 April, I plan to review my two current reads, Cocktail by Lisa Alward and Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang, and concoct a personal wish list.

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot. A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age. In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).