200 Names for a Cat

Winter weather. Impeachment hearings. An impending election. There are any number of things that might be getting you down on this early December day, so it’s time for something cheery.

For once I don’t have something book-related to post. Instead, I think this list of 200 nicknames we have called our cat deserves to see the light of day. For the record, the cat’s actual name is Alfie. Some nicknames are literal and some are fanciful. A few are downright embarrassing, but I’m going to go ahead and post them all; surely you’ve called your (fur)baby by some ridiculous names? Others are gentle slurs about his weight, though he has lost about 1 kg this year. Some have to do with his occasional sullenness or outright meanness. But he’s a lovely creature, really. I marvel sometimes that we let a tiny carnivore share our bed every night. We’re so used to it that we wouldn’t have it any other way.

A few of my favorite nicknames are: Alfred the Ingrate, Furry McPurrface, G.K. (Grumpy Kitty) Chatterton, Grumblepuss, Imperious Blinker, Kitten Pot Pie, Monsieur Poire, Podgebelly and Smugtopuss.

For the whole list, click here. It’s in alphabetical order.

From Scatty by Siné, a French comics artist.

Which is your favorite?

20 Books of Summer, #1–4: Alexis, Haupt, Rutt, Tovey

I was slow to launch into my 20 Books of Summer reading, but have now finally managed to get through my first four books. These include two substitutes: a review copy I hadn’t realized fit in perfectly with my all-animals challenge, and a book I’d started earlier in the year but set aside and wanted to get back into. Three of the four were extremely rewarding; the last was somewhat insubstantial, though I always enjoy reading about cat antics. All have been illuminating about animal intelligence and behavior, and useful for thinking about our place in and duty towards the more-than-human world. Not all of my 20 Books of Summer will have such an explicit focus on nature – some just happen to have an animal in the title or pictured on the cover – but this first batch had a strong linking theme so was a great start.

Fifteen Dogs by André Alexis (2015)

In this modern folk tale with elements of the Book of Job, the gods Apollo and Hermes, drinking in a Toronto tavern, discuss the nature of human intelligence and ponder whether it’s inevitably bound up with suffering. They decide to try an experiment, and make a wager on it. They’ll bestow human intelligence on a set of animals and find out whether the creatures die unhappy. Apollo is willing to bet two years’ personal servitude that they will be even unhappier than humans. Their experimental subjects are the 15 dogs being boarded overnight at a nearby veterinary clinic.

The setup means we’re in for an And Then There Were None type of picking-off of the 15, and some of the deaths are distressing. But strangely – and this is what the gods couldn’t foresee – knowledge of their approaching mortality gives the dogs added dignity. It gives their lives and deaths the weight of Shakespearean tragedy. Although they still do doggy things like establishing dominance structures and eating poop, they also know the joys of language and love. A mutt called Prince composes poetry and jokes. Benjy the beagle learns English well enough to recite the first paragraph of Vanity Fair. A poodle named Majnoun forms a connection with his owner that lasts beyond the grave. The dogs work out who they can trust; they form and dissolve bonds; they have memories and a hope that lives on.

The setup means we’re in for an And Then There Were None type of picking-off of the 15, and some of the deaths are distressing. But strangely – and this is what the gods couldn’t foresee – knowledge of their approaching mortality gives the dogs added dignity. It gives their lives and deaths the weight of Shakespearean tragedy. Although they still do doggy things like establishing dominance structures and eating poop, they also know the joys of language and love. A mutt called Prince composes poetry and jokes. Benjy the beagle learns English well enough to recite the first paragraph of Vanity Fair. A poodle named Majnoun forms a connection with his owner that lasts beyond the grave. The dogs work out who they can trust; they form and dissolve bonds; they have memories and a hope that lives on.

It’s a fascinating and inventive novella, and a fond treatment of the relationship between dogs and humans. When I read in the Author’s Note that the poems all included dogs’ names, I went right back to the beginning to scout them out. I’m intrigued by the fact that this Giller Prize winner is a middle book in a series, and keen to explore the rest of the Trinidanian-Canadian author’s oeuvre.

These next two have a lot in common. For both authors, paying close attention to the natural world – birds, in particular – is a way of coping with environmental and mental health crises.

Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness by Lyanda Lynn Haupt (2009)

Lyanda Lynn Haupt has worked in bird research and rehabilitation for the Audubon Society and other nature organizations. (I read her first book, Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds, quite a few years ago.) During a bout of depression, she decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. From then on she took binoculars everywhere she went, even on walks to Target. She spent time watching crows’ behavior from a distance or examining them up close – devoting hours to studying a prepared crow skin. She even temporarily took in a broken-legged fledgling she named Charlotte and kept a close eye on the injured bird’s progress in the months after she released it.

Lyanda Lynn Haupt has worked in bird research and rehabilitation for the Audubon Society and other nature organizations. (I read her first book, Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds, quite a few years ago.) During a bout of depression, she decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. From then on she took binoculars everywhere she went, even on walks to Target. She spent time watching crows’ behavior from a distance or examining them up close – devoting hours to studying a prepared crow skin. She even temporarily took in a broken-legged fledgling she named Charlotte and kept a close eye on the injured bird’s progress in the months after she released it.

Were this simply a charming and keenly observed record of bird behavior and one woman’s gradual reawakening to the joys of nature, I would still have loved it. Haupt is a forthright and gently witty writer. But what takes it well beyond your average nature memoir is the bold statement of human responsibility to the environment. I’ve sat through whole conference sessions that try to define what nature is, what the purpose of nature writing is, and so on. Haupt can do it in just a sentence, concisely and effortlessly explaining how to be a naturalist in a time of loss and how to hope even when in possession of all the facts.

A few favorite passages:

“an intimate awareness of the continuity between our lives and the rest of life is the only thing that will truly conserve the earth … When we allow ourselves to think of nature as something out there, we become prey to complacency. If nature is somewhere else, then what we do here doesn’t really matter.”

“I believe strongly that the modern naturalist’s calling includes an element of activism. Naturalists are witnesses to the wild, and necessary bridges between ecological and political ways of knowing. … We join the ‘cloud of witnesses’ who refuse to let the more-than-human world pass unnoticed.”

“here we are, intricate human animals capable of feeling despair over the state of the earth and, simultaneously, joy in its unfolding wildness, no matter how hampered. What are we to do with such a confounding vision? The choices appear to be few. We can deny it, ignore it, go insane with its weight, structure it into a stony ethos with which we beat our friends and ourselves to death—or we can live well in its light.”

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt (2019)

In 2016 Rutt left his anxiety-inducing life in London in a search for space and silence. He found plenty of both on the Orkney Islands, where he volunteered at the North Ronaldsay bird observatory for seven months. In the few years that followed, the young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. He’s surrounded by storm petrels one magical night at Mousa Broch; he runs from menacing skuas; he watches eider and terns and kittiwakes along the northeast coast; he returns to Orkney to marvel at gannets and fulmars. Whether it’s their beauty, majesty, resilience, or associations with freedom, such species are for him a particularly life-enhancing segment of nature to spend time around.

In 2016 Rutt left his anxiety-inducing life in London in a search for space and silence. He found plenty of both on the Orkney Islands, where he volunteered at the North Ronaldsay bird observatory for seven months. In the few years that followed, the young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. He’s surrounded by storm petrels one magical night at Mousa Broch; he runs from menacing skuas; he watches eider and terns and kittiwakes along the northeast coast; he returns to Orkney to marvel at gannets and fulmars. Whether it’s their beauty, majesty, resilience, or associations with freedom, such species are for him a particularly life-enhancing segment of nature to spend time around.

Discussion of the environmental threats that hit seabirds hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider conservation issues. Rutt also sees himself as part of a long line of bird-loving travellers, including James Fisher and especially R.M. Lockley, whose stories he weaves in. This is one of the best nature/travel books I’ve read in a long time, especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations and the elegantly evocative writing, making particularly effective use of varied sentence lengths, brought back to me just what it’s like to be in the far north of Scotland in the midst of an endless summer twilight, a humbled observer as a whole whirlwind of bird life carries on above you.

A favorite passage:

“Gannets nest on the honeycombs of the cliff, in their thousands. They sit in pairs, pointing to the sky, swaying heads. They stir. The scent of the boat’s herring fills the air. They take off, tessellating in a sky that is suddenly as much bird as light. The great skuas lurk.”

My husband also reviewed this, from a birder’s perspective.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the proof copy for review.

The Coming of Saska by Doreen Tovey (1977)

I’ve read four of Tovey’s quaint Siamese cat books now; this was the least worthwhile. It’s partially a matter of false advertising: Saska only turns up for the last 15 pages, as a replacement of sorts for Seeley, who disappeared one morning a year earlier and was never seen again. Over half of the book, in fact, is about a trip Tovey and her husband Charles took to Edmonton, Canada. The Canadian government sponsored them to come over for the Klondike Days festivities, and they also rented a camper and went looking for bears and moose. Mildly amusing mishaps, close shaves, etc. ensue. They then come back and settle into everyday life with their pair of Siamese half-siblings; Saska had the same father as Shebalu. Entertaining enough, but slight, and with far too many ellipses.

I’ve read four of Tovey’s quaint Siamese cat books now; this was the least worthwhile. It’s partially a matter of false advertising: Saska only turns up for the last 15 pages, as a replacement of sorts for Seeley, who disappeared one morning a year earlier and was never seen again. Over half of the book, in fact, is about a trip Tovey and her husband Charles took to Edmonton, Canada. The Canadian government sponsored them to come over for the Klondike Days festivities, and they also rented a camper and went looking for bears and moose. Mildly amusing mishaps, close shaves, etc. ensue. They then come back and settle into everyday life with their pair of Siamese half-siblings; Saska had the same father as Shebalu. Entertaining enough, but slight, and with far too many ellipses.

“Cat Poems” & Other Cats I’ve Encountered in Books Recently

Cat Poems: An enjoyable selection of verse about our feline friends, nicely varied in terms of the time period, original language of composition, and outlook on cats’ contradictory qualities. I was unaware that Angela Carter and Muriel Spark had ever written poetry. There are perhaps too many poems by Stevie Smith – six in total! – though I did enjoy their jokey rhymes.

Cat Poems: An enjoyable selection of verse about our feline friends, nicely varied in terms of the time period, original language of composition, and outlook on cats’ contradictory qualities. I was unaware that Angela Carter and Muriel Spark had ever written poetry. There are perhaps too many poems by Stevie Smith – six in total! – though I did enjoy their jokey rhymes.

Some favorite lines:

“Cat sentimentality is a human thing. Cats / are indifferent, their minds can’t comprehend / the concept ‘I shall die’, they just go on living.” (from “Sonnet: Cat Logic” by Gavin Ewart)

“For every house is incomplete without him and a blessing is lacking in the spirit.” (from “Jubilate Agno” by Christopher Smart)

“These adorable things. When my life gives out, they’d eat me up in a second.” (from “I’ll Call Those Things My Cats” by Kim Hyesoon)

My rating:

Cat Poems was published in the UK on October 4th. My thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the free copy for review.

Even when it’s not a book specifically about cats, cats often turn up in my reading. Maybe it’s simply that I look out for them more since I became a cat owner several years ago. Here are some of the quotes, scenes or whole books featuring cats that I’ve come across this year.

Cats real and imaginary

Stranger on a Train by Jenni Diski: “I find myself astonished that a creature of another species, utterly different to me, honours me with its presence and trust by sitting on me and allowing me to stroke it. This mundane domestic moment is as enormous, I feel at such moments, as making contact across a universe with another intelligence. This creature with its own and other consciousness and I with mine can sit in silence and enjoy each other’s presence. … This is a perfectly everyday scene but sometimes it takes my breath away that another living thing has allowed me into its life.”

Stranger on a Train by Jenni Diski: “I find myself astonished that a creature of another species, utterly different to me, honours me with its presence and trust by sitting on me and allowing me to stroke it. This mundane domestic moment is as enormous, I feel at such moments, as making contact across a universe with another intelligence. This creature with its own and other consciousness and I with mine can sit in silence and enjoy each other’s presence. … This is a perfectly everyday scene but sometimes it takes my breath away that another living thing has allowed me into its life.”

Certain American States by Catherine Lacey: “This cat wants to destroy beauty—I can tell. He is more than animal, he is evil, a plain enemy of the world. I wish him ill. I do. Almost daily I find a mess of feathers in the dirt. Some mornings there are whole bird carcasses left on my porch—eyes shocked open, brilliant blue wings, ripped and bloody. I have thought often of what it would take to kill a cat, quietly and quickly, with my bare hands. I have thought of this often. In fact I am thinking of it right now.” (from the story “Because You Have To”)

Certain American States by Catherine Lacey: “This cat wants to destroy beauty—I can tell. He is more than animal, he is evil, a plain enemy of the world. I wish him ill. I do. Almost daily I find a mess of feathers in the dirt. Some mornings there are whole bird carcasses left on my porch—eyes shocked open, brilliant blue wings, ripped and bloody. I have thought often of what it would take to kill a cat, quietly and quickly, with my bare hands. I have thought of this often. In fact I am thinking of it right now.” (from the story “Because You Have To”)

The Nice and the Good by Iris Murdoch: “Montrose was a large cocoa-coloured tabby animal with golden eyes, a square body, rectangular legs and an obstinate self-absorbed disposition, concerning whose intelligence fierce arguments raged among the children. Tests of Montrose’s sagacity were constantly being devised, but there was some uncertainty about the interpretation of the resultant data since the twins were always ready to return to first principles and discuss whether cooperation with the human race was a sign of intelligence at all. Montrose had one undoubted talent, which was that he could at will make his sleek hair stand up on end, and transform himself from a smooth stripey cube into a fluffy sphere. This was called ‘Montrose’s bird look’.”

The Nice and the Good by Iris Murdoch: “Montrose was a large cocoa-coloured tabby animal with golden eyes, a square body, rectangular legs and an obstinate self-absorbed disposition, concerning whose intelligence fierce arguments raged among the children. Tests of Montrose’s sagacity were constantly being devised, but there was some uncertainty about the interpretation of the resultant data since the twins were always ready to return to first principles and discuss whether cooperation with the human race was a sign of intelligence at all. Montrose had one undoubted talent, which was that he could at will make his sleek hair stand up on end, and transform himself from a smooth stripey cube into a fluffy sphere. This was called ‘Montrose’s bird look’.”

Four Bare Legs in a Bed and Other Stories by Helen Simpson: “They found it significant that I called my cat Felony. I argued that I had chosen her name for its euphonious qualities. She used to sink her incisors into the hell of my hand and pause a fraction of a millimeter from breaking the skin, staring at me until her eyes were reduced to sadistic yellow semibreves. She murdered without a qualm. She toyed with her victims, smiling broadly at their squeaks and death throes.

Four Bare Legs in a Bed and Other Stories by Helen Simpson: “They found it significant that I called my cat Felony. I argued that I had chosen her name for its euphonious qualities. She used to sink her incisors into the hell of my hand and pause a fraction of a millimeter from breaking the skin, staring at me until her eyes were reduced to sadistic yellow semibreves. She murdered without a qualm. She toyed with her victims, smiling broadly at their squeaks and death throes.

‘Why isn’t she a criminal?’ I asked. …

‘The difference is,’ said Mr Pringle, that we must assume your cat commits her crimes without mischievous discretion.’” (from the story “Escape Clauses”)

In Delia Owens’s Where the Crawdads Sing, Sunday Justice is the name of the courthouse cat. He sits grooming on the courtroom windowsill during the trial and comes in and curls up to sleep in the cell of a particular prisoner we’ve come to care about.

In Delia Owens’s Where the Crawdads Sing, Sunday Justice is the name of the courthouse cat. He sits grooming on the courtroom windowsill during the trial and comes in and curls up to sleep in the cell of a particular prisoner we’ve come to care about.

A recommended picture book

My Cat Looks Like My Dad by Thao Lam: I absolutely loved the papercut collage style of this kids’ book. The narrator explains all the ways in which the nerdy-cool 1970s-styled dad resembles the family cat, who is more like a sibling than a pet. “Family is what you make it.” There’s something of a twist ending, too. (Out on April 15, 2019.)

My Cat Looks Like My Dad by Thao Lam: I absolutely loved the papercut collage style of this kids’ book. The narrator explains all the ways in which the nerdy-cool 1970s-styled dad resembles the family cat, who is more like a sibling than a pet. “Family is what you make it.” There’s something of a twist ending, too. (Out on April 15, 2019.)

My rating:

Later today I’m off to America for two weeks, but I’ll be scheduling plenty of posts, including the usual multi-part year-end run-down of my best reads, to go up while I’m away. Forgive me if I’m less responsive than usual to comments and to your own blogs!

An Untranslatable Term for International Translation Day

Today is International Translation Day, so I’m sharing my favorite spread from In Other Words: An Illustrated Miscellany of the World’s Most Intriguing Words and Phrases by Christopher J. Moore (foreword by Simon Winchester), which came out from Modern Press last year. It’s a collection of the linguist/translator’s 80 favorite untranslatable expressions.

#Internationaltranslationday #InOtherWords @modernbooks

My thanks to Alison Menzies PR for sending a copy of the e-book.

Heart and Mind: New Nonfiction by Sandeep Jauhar and Jan Morris

Heart: A History, by Sandeep Jauhar

There could hardly be an author better qualified to deliver this thorough history of the heart and the treatment of its problems. Sandeep Jauhar is the director of the Heart Failure Program at Long Island Medical Center. His family history – both grandfathers died of sudden cardiac events in India, one after being bitten by a snake – prompted an obsession with the heart, and he and his brother both became cardiologists. As the book opens, Jauhar was shocked to learn he had up to a 50% blockage of his own coronary vessels. Things had really gotten personal.

Cardiovascular disease has been the #1 killer in the West since 1910 and, thanks to steady smoking rates and a continuing rise in obesity and sedentary lifestyles, will still affect 60% of Americans. However, the key is that fewer people will now die of heart disease thanks to the developments of the last six decades in particular. These include the heart–lung machine, cardiac catheterization, heart transplantation, and artificial hearts.

Along the timeline, Jauhar peppers in bits of his own professional and academic experience, like experimenting on frogs during high school in California and meeting his first cadaver at medical school. My favorite chapter was the twelfth, “Vulnerable Heart,” which is about how trauma can cause heart arrhythmias; it opens with an account of the author’s days cataloguing body parts in a makeshift morgue as a 9/11 first responder. I also particularly liked his account of being called out of bed to perform an echocardiogram, which required catching a taxi at 3 a.m. and avoiding New York City’s rats.

Along the timeline, Jauhar peppers in bits of his own professional and academic experience, like experimenting on frogs during high school in California and meeting his first cadaver at medical school. My favorite chapter was the twelfth, “Vulnerable Heart,” which is about how trauma can cause heart arrhythmias; it opens with an account of the author’s days cataloguing body parts in a makeshift morgue as a 9/11 first responder. I also particularly liked his account of being called out of bed to perform an echocardiogram, which required catching a taxi at 3 a.m. and avoiding New York City’s rats.

Maybe I’ve read too much surgical history this year (The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris and Face to Face by Jim McCaul), though, because I found myself growing fairly impatient with the medical details in the long Part II, which centers on the heart as a machine, and was drawn more to the autobiographical material in the first and final sections. Perhaps I would prefer Jauhar’s first book, Intern: A Doctor’s Initiation.

In terms of readalikes, I’d mention Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene, in which the personal story also takes something of a backseat to the science, and Gavin Francis’s Shapeshifters, which exhibits a similar interest in the metaphors applied to the body. While I didn’t enjoy this quite as much as two other heart-themed memoirs I’ve read, The Sanctuary of Illness by Thomas Larson and Echoes of Heartsounds by Martha Weinman Lear, I still think it’s a strong contender for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize (the judging panel is announced tomorrow!).

Some favorite lines:

“it is increasingly clear that the biological heart is extraordinarily sensitive to our emotional system—to the metaphorical heart, if you will.”

“Who but the owner can say what lies inside a human heart?”“As a heart-failure specialist, I’d experienced enough death to fill up a lifetime. At one time, it was difficult to witness the grief of loved ones. But my heart had been hardened, and this was no longer that time.”

My rating:

Heart is published in the UK today, September 27th, by Oneworld. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

In My Mind’s Eye: A Thought Diary, by Jan Morris

I’ve been an admirer of Jan Morris’s autobiographical and travel writing for 15 years or more. In this diary covering 2017 into early 2018, parts of which were originally published in the Financial Times and the Welsh-language literary newspaper O’r Pedwar Gwynt, we get a glimpse into her life in her early nineties. It was a momentous time in the world at large but a fairly quiet and reflective span for her personally. Though each day’s headlines seem to herald chaos and despair, she’s a blithe spirit – good-natured about the ravages of old age and taking delight in the routines of daily one-mile walks down the lane and errands in local Welsh towns with her beloved partner Elizabeth, who’s in the early stages of dementia.

There are thrilling little moments, though, when a placid domestic life (a different kind of marmalade with breakfast each day of the week!) collides with exotic past experiences, and suddenly we’re plunged into memories of travels in Swaziland and India. Back when she was still James, Morris served in World War II, was the Times journalist reporting from the first ascent of Everest, and wrote a monolithic three-volume history of the British Empire. She took her first airplane flight 70 years ago, and is nostalgic for the small-town America she first encountered in the 1950s. Hold all that up against her current languid existence among the books and treasures of Trefan Morys and it seems she’s lived enough for many lifetimes.

There are thrilling little moments, though, when a placid domestic life (a different kind of marmalade with breakfast each day of the week!) collides with exotic past experiences, and suddenly we’re plunged into memories of travels in Swaziland and India. Back when she was still James, Morris served in World War II, was the Times journalist reporting from the first ascent of Everest, and wrote a monolithic three-volume history of the British Empire. She took her first airplane flight 70 years ago, and is nostalgic for the small-town America she first encountered in the 1950s. Hold all that up against her current languid existence among the books and treasures of Trefan Morys and it seems she’s lived enough for many lifetimes.

There’s a good variety of topics here, ranging from current events to Morris’s love of cats; I particularly liked the fragments of doggerel. However, as is often the case with diaries, read too many entries in one go and you may start to find the sequence of (non-)events tedious. Each piece is only a page or two, so I tried never to read many more than 10 pages at a time. Even so, I noticed that the plight of zoo animals, clearly a hobby-horse, gets mentioned several times. It seemed to me a strange issue to get worked up about, especially as enthusiastic meat-eating and killing mice with traps suggest that she’s not applying a compassionate outlook consistently.

In the end, though, kindness is Morris’s cardinal virtue, and despite minor illness, telephone scams and a country that looks to be headed to the dogs, she’s encouraged by the small acts of kindness she meets with from friends and strangers alike. Like Diana Athill (whose Alive, Alive Oh! this resembles), I think of Morris as a national treasure, and I was pleased to spend some time seeing things from her perspective.

Some favorite lines:

“If I set out in the morning for my statutory thousand daily paces up the lane, … I enjoy the fun of me, the harmless conceit, the guileless complexity and the merriment. When I go walking in the evening, on the other hand, … I shall recognize what I don’t like about myself – selfishness, self-satisfaction, foolish self-deceit and irritability. Morning pride, then, and evening shame.” (from Day 99)

“Good or bad, virile or senile, there’s no life like the writer’s life.” (from Day 153)

My rating:

In My Mind’s Eye was published by Faber & Faber on September 6th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Still More Books about Cats

The past two years I’ve had biannual specials on cat books. You might think I would have run out of options by now, but not so! Granted, my choices this time are rather light fare: several children’s picture books, two slight gift books, and a few breezy memoirs. But it’s nice to have a fluffy post every now and again, and today’s is in honor of getting past a week of the year I always dread: June 15th is the U.S. tax deadline for citizens living abroad, so I’ve been drowning in forms and numbers. To celebrate getting both my IRS and HMRC tax returns sent off by today, here’s some feline-themed reads to enjoy over a G&T or other summery tipple of your choice.

Alfie likes cat books, too. The stacks are good for scratching one’s cheek against.

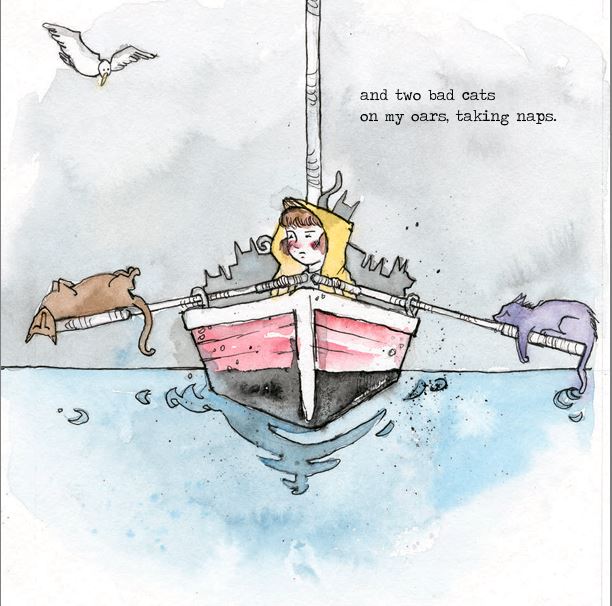

Seven Bad Cats by Monique Bonneau (2018): “Today I put on my boots and my coat, and seven bad cats jumped into my boat.” This is a terrific little rhyming book that counts up to seven and then back down to one with the help of some stowaway cats and their antics. (They come in colors that cats don’t normally come in, but that’s okay with me.) To start with they are incorrigibly lazy and mischievous, but when disaster is at hand they band together to help the little girl get back to shore safely. If only cats were so helpful in real life!

Seven Bad Cats by Monique Bonneau (2018): “Today I put on my boots and my coat, and seven bad cats jumped into my boat.” This is a terrific little rhyming book that counts up to seven and then back down to one with the help of some stowaway cats and their antics. (They come in colors that cats don’t normally come in, but that’s okay with me.) To start with they are incorrigibly lazy and mischievous, but when disaster is at hand they band together to help the little girl get back to shore safely. If only cats were so helpful in real life!

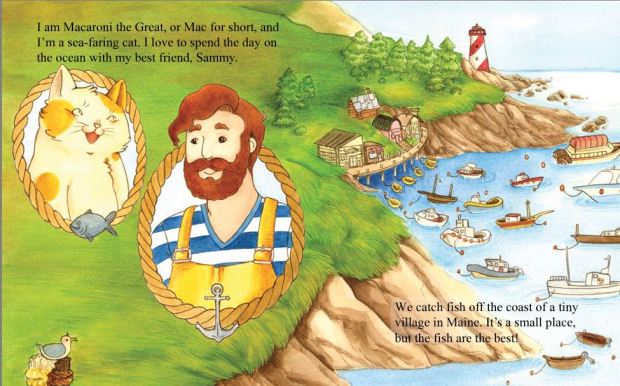

Macaroni the Great and the Sea Beast by Whitney Childers (2018): Macaroni the cat has an idyllic life by the coast of Maine with his hipster fisherman friend, Sammy. Sometimes he helps steer the fishing boat; sometimes he naps on the deck. But when a fearsome sea beast rears its head from the net one day, Mac is ready to fight back and save the day. From the colorfully nautical endpapers through to the peaceful last page, this is a great picture book for cat lovers to share with the little ones in their lives.

Macaroni the Great and the Sea Beast by Whitney Childers (2018): Macaroni the cat has an idyllic life by the coast of Maine with his hipster fisherman friend, Sammy. Sometimes he helps steer the fishing boat; sometimes he naps on the deck. But when a fearsome sea beast rears its head from the net one day, Mac is ready to fight back and save the day. From the colorfully nautical endpapers through to the peaceful last page, this is a great picture book for cat lovers to share with the little ones in their lives.

You don’t so often hear blokes talking about their cats, do you? That crazy cat lady stereotype dominates. But Tom Cox has written several memoirs about his life with cats.

In Under the Paw: Confessions of a Cat Man (2008), Cox, who had previously published volumes of his journalism about music and sports, came out as a cat lover. By the end of the book he has SIX CATS, so this was not some passing fad but a deep and possibly worrying obsession. In essays and short list-based asides he traces his history with cats, reveals the wildly different personalities of his current pets, and wittily comments on cat behavior. I especially liked these entries from his “Cat Dictionary”: “ES Pee: The telepathic process that leads a cat to only get properly settled on its owner’s stomach in the moments when that owner is most desperate for the toilet” & “Muzzlewug: The state of bliss created by the perfect friction of an owner’s fingers on a fully extended chin.”

In Under the Paw: Confessions of a Cat Man (2008), Cox, who had previously published volumes of his journalism about music and sports, came out as a cat lover. By the end of the book he has SIX CATS, so this was not some passing fad but a deep and possibly worrying obsession. In essays and short list-based asides he traces his history with cats, reveals the wildly different personalities of his current pets, and wittily comments on cat behavior. I especially liked these entries from his “Cat Dictionary”: “ES Pee: The telepathic process that leads a cat to only get properly settled on its owner’s stomach in the moments when that owner is most desperate for the toilet” & “Muzzlewug: The state of bliss created by the perfect friction of an owner’s fingers on a fully extended chin.”

The Good, the Bad and the Furry (2013) is another fairly entertaining book. Cat owners will recognize the ways in which a pet’s requirements impinge on their lives (but we wouldn’t have it any other way). Cox starts and ends the book with four cats, but – alas – goes down to three for a while in the middle, with visitors upping it to 3.5 sometimes. The Bear, Ralph and Shipley are the stalwarts, with The Bear described as “the only cat I’d ever seen who appeared to be almost permanently on the verge of tears.” He’s melancholy and philosophical, whereas Ralph (who says his own name when he meows) is vain and sullen. “The Ten Catmandments” was my favorite part: “Thou shalt not drink the water put out for thee by thy humans” and “Thou shalt ignore any toy thy human has bought for thee, especially the really expensive ones.” Includes lots of photographs of cats and kittens!

The Good, the Bad and the Furry (2013) is another fairly entertaining book. Cat owners will recognize the ways in which a pet’s requirements impinge on their lives (but we wouldn’t have it any other way). Cox starts and ends the book with four cats, but – alas – goes down to three for a while in the middle, with visitors upping it to 3.5 sometimes. The Bear, Ralph and Shipley are the stalwarts, with The Bear described as “the only cat I’d ever seen who appeared to be almost permanently on the verge of tears.” He’s melancholy and philosophical, whereas Ralph (who says his own name when he meows) is vain and sullen. “The Ten Catmandments” was my favorite part: “Thou shalt not drink the water put out for thee by thy humans” and “Thou shalt ignore any toy thy human has bought for thee, especially the really expensive ones.” Includes lots of photographs of cats and kittens!

How It Works: The Cat (2016) is a Ladybird pastiche by Jason Hazeley and Joel Morris that we purchased as a bargain book from Aldi; it was published in the USA as The Fireside Book of the Cat. Tongue-in-cheek descriptions sit opposite 1950s-style drawings. Cat owners will certainly get a chuckle from lines like “Dogs have evolved to serve many sorts of human needs. And humans have evolved to serve many sorts of cat food.” (However, “It is a good idea to buy a lot of your cat’s favourite food. That way, you will have something to throw away when she changes her mind.”) Makes a good coffee table book for guests to smile at.

How It Works: The Cat (2016) is a Ladybird pastiche by Jason Hazeley and Joel Morris that we purchased as a bargain book from Aldi; it was published in the USA as The Fireside Book of the Cat. Tongue-in-cheek descriptions sit opposite 1950s-style drawings. Cat owners will certainly get a chuckle from lines like “Dogs have evolved to serve many sorts of human needs. And humans have evolved to serve many sorts of cat food.” (However, “It is a good idea to buy a lot of your cat’s favourite food. That way, you will have something to throw away when she changes her mind.”) Makes a good coffee table book for guests to smile at.

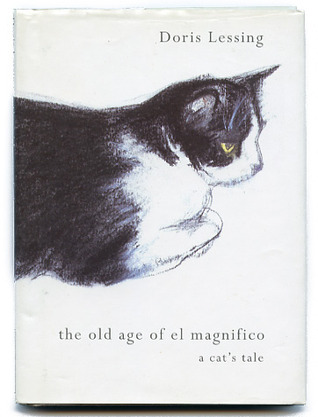

The Old Age of El Magnifico by Doris Lessing (2000): Pure cat lover’s delight. I wasn’t a big fan of Lessing’s Particularly Cats, which is surprisingly unsentimental and even brutal in places. This redresses the balance. It’s the bittersweet story of Butch, her enormous black and white cat, who was known by many additional nicknames including El Magnifico. At the age of 14 he was found to have a cancerous growth in his shoulder, and one entire front leg had to be removed. His habits, and even to an extent his personality, changed after the amputation, and Lessing regretted that she couldn’t let him know it was done for his good. She reflects on her duty towards the cats in her care, and on how pets encourage us to slow our pace and direct our attention fully to the present moment. Work? Chores? Worries? What could really be more important than sitting still and stroking a cat?

The Old Age of El Magnifico by Doris Lessing (2000): Pure cat lover’s delight. I wasn’t a big fan of Lessing’s Particularly Cats, which is surprisingly unsentimental and even brutal in places. This redresses the balance. It’s the bittersweet story of Butch, her enormous black and white cat, who was known by many additional nicknames including El Magnifico. At the age of 14 he was found to have a cancerous growth in his shoulder, and one entire front leg had to be removed. His habits, and even to an extent his personality, changed after the amputation, and Lessing regretted that she couldn’t let him know it was done for his good. She reflects on her duty towards the cats in her care, and on how pets encourage us to slow our pace and direct our attention fully to the present moment. Work? Chores? Worries? What could really be more important than sitting still and stroking a cat?

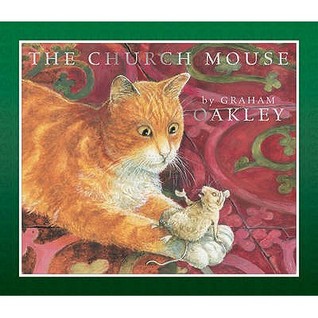

The Church Mouse by Graham Oakley: It is not good for a mouse to be alone. Arthur is lonely as the only mouse resident in the village church, but he has an idea: he proposes to the parson that if he will give all the local mice refuge in the church, they’ll undertake minor chores like flower arranging and picking up confetti. It seems like a good arrangement all around, but Sampson the church cat soon tires of the mice’s antics and creates something of a scene during a Sunday service. Luckily, he and the mice still work together to outwit a burglar who comes for the silver. There are quite a lot of words for a very small child to engage with, but older children should enjoy it very much. I find this whole series so charming. This was the first book of the 14, from 1972.

The Church Mouse by Graham Oakley: It is not good for a mouse to be alone. Arthur is lonely as the only mouse resident in the village church, but he has an idea: he proposes to the parson that if he will give all the local mice refuge in the church, they’ll undertake minor chores like flower arranging and picking up confetti. It seems like a good arrangement all around, but Sampson the church cat soon tires of the mice’s antics and creates something of a scene during a Sunday service. Luckily, he and the mice still work together to outwit a burglar who comes for the silver. There are quite a lot of words for a very small child to engage with, but older children should enjoy it very much. I find this whole series so charming. This was the first book of the 14, from 1972.

Cats in May by Doreen Tovey (1959): The sequel is just as good as the original (Cats in the Belfry). Along with feline antics we get the adventures of Blondin the squirrel, whom Tovey and her husband adopted before they started keeping Siamese cats. (He was just as destructive as the pets that came after him, but I had to love his fondness for tea.) Solomon and Sheba appear on the BBC and object in the strongest possible terms when Doreen and Charles try to introduce a third Siamese, a kitten named Samson, to the household. The flu, visits from the rector’s grandson, and periodic troubles with their old farmhouse, including a chimney fire, round out this highly amusing story of life with pets.

Cats in May by Doreen Tovey (1959): The sequel is just as good as the original (Cats in the Belfry). Along with feline antics we get the adventures of Blondin the squirrel, whom Tovey and her husband adopted before they started keeping Siamese cats. (He was just as destructive as the pets that came after him, but I had to love his fondness for tea.) Solomon and Sheba appear on the BBC and object in the strongest possible terms when Doreen and Charles try to introduce a third Siamese, a kitten named Samson, to the household. The flu, visits from the rector’s grandson, and periodic troubles with their old farmhouse, including a chimney fire, round out this highly amusing story of life with pets.

Not all cat books are winners. Here are two that, alas, I cannot recommend:

The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (2017): This is the fable-like story of Satoru, a single man in his early thirties, and his cat, Nana (named for the shape of his tail, which resembles a Japanese 7). Satoru adopted Nana about five years ago when the cat, a local stray, was hit by a car. Now he needs to find a new owner for his beloved pet. No spoilers here, but really, there are only so many reasons why a young man would need to do this, and readers will likely work it out well before the “big reveal” over halfway through. We bounce between Nana’s perspective, which is quite cutely rendered, and third-person flashbacks to Satoru’s sad history. The author spells out and overstates everything. It’s pretty emotionally manipulative. Pet owners will appreciate Nana’s humor and loyalty (“I’m your cat till the bitter end!”), but I felt like I was being brow-beaten into crying – though I didn’t in the end.

The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (2017): This is the fable-like story of Satoru, a single man in his early thirties, and his cat, Nana (named for the shape of his tail, which resembles a Japanese 7). Satoru adopted Nana about five years ago when the cat, a local stray, was hit by a car. Now he needs to find a new owner for his beloved pet. No spoilers here, but really, there are only so many reasons why a young man would need to do this, and readers will likely work it out well before the “big reveal” over halfway through. We bounce between Nana’s perspective, which is quite cutely rendered, and third-person flashbacks to Satoru’s sad history. The author spells out and overstates everything. It’s pretty emotionally manipulative. Pet owners will appreciate Nana’s humor and loyalty (“I’m your cat till the bitter end!”), but I felt like I was being brow-beaten into crying – though I didn’t in the end.

I Could Pee on This, Too: And More Poems by More Cats by Francesco Marciuliano (2016): Not a single memorable poem or line in the lot. Seriously. Stick with the original.

My next batch of cat books. Maybe I’ll try to write them up for a Christmas-tide treat.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.)

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.) Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also  Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right.

Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right. The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be.

The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be. The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong.

The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong. Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.”

Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.” All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning.

All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning. Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife.

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife. My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”).

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”). On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)

On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)  “Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the

“Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the  Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)  Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)  Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)

Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)  They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well.

They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well. Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community.

Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community. This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing?

This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing? I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.

I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.

I knew Tom Cox for his

I knew Tom Cox for his  Nobody “Bod” Owens has lived in a graveyard ever since the night he climbed out of his cot and toddled there – the same night that a man named Jack murdered his parents and older sister. He was the only member of his family to survive the slaughter. Although he passes a happy childhood among the graveyard’s witches, ghouls and ghosts from many centuries, he knows he’s different. He’s alive; he has to eat and craves human friendship. As valuable as his lessons in Fading and Dreamwalking prove to be, he longs to attend school and discover more of the world outside – provided he can keep his head down and avoid notice; previous trips beyond the cemetery walls, such as to a pawnshop, have bordered on the disastrous.

Nobody “Bod” Owens has lived in a graveyard ever since the night he climbed out of his cot and toddled there – the same night that a man named Jack murdered his parents and older sister. He was the only member of his family to survive the slaughter. Although he passes a happy childhood among the graveyard’s witches, ghouls and ghosts from many centuries, he knows he’s different. He’s alive; he has to eat and craves human friendship. As valuable as his lessons in Fading and Dreamwalking prove to be, he longs to attend school and discover more of the world outside – provided he can keep his head down and avoid notice; previous trips beyond the cemetery walls, such as to a pawnshop, have bordered on the disastrous. In 1935 Dr. Stephen Pearce and his brother Kits are part of a five-man mission to climb the most dangerous mountain in the Himalayas, Kangchenjunga. Thirty years before, Sir Edmund Lyell led an ill-fated expedition up the same mountain: more than one man did not return, and the rest lost limbs to frostbite. “I don’t want to know what happened to them. It’s in the past. It has nothing to do with us,” Dr. Pearce tells himself, but from the start it feels like a bad omen that they, like Lyell’s party, are attempting the southwest approach; even the native porters are nervous. And as they climb, they fall prey to various medical and mental crises; hallucinations of ghostly figures on the crags are just as much of a danger as snow blindness.

In 1935 Dr. Stephen Pearce and his brother Kits are part of a five-man mission to climb the most dangerous mountain in the Himalayas, Kangchenjunga. Thirty years before, Sir Edmund Lyell led an ill-fated expedition up the same mountain: more than one man did not return, and the rest lost limbs to frostbite. “I don’t want to know what happened to them. It’s in the past. It has nothing to do with us,” Dr. Pearce tells himself, but from the start it feels like a bad omen that they, like Lyell’s party, are attempting the southwest approach; even the native porters are nervous. And as they climb, they fall prey to various medical and mental crises; hallucinations of ghostly figures on the crags are just as much of a danger as snow blindness.