Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

The Single Hound by May Sarton (1938)

I spotted that the 30th anniversary of May Sarton’s death was coming up, so decided to read an unread book of hers from my shelves in time to mark the occasion. Today’s the day: she died on July 16, 1995 in York, Maine. Marcie of Buried in Print joined me for a buddy read (her review). I was drawn by the title, which comes from an Emily Dickinson quote. It’s the ninth Sarton novel I’ve read and, while in general I find her nonfiction more memorable than her fiction, this impressionistic debut novel was a solid read. It was clearly inspired by Virginia Woolf’s work and based on Sarton’s memories of her time on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

the three together made a complete world.

Was this life? This slow penetration of experience until nothing had been left untasted, unexplored, unused — until the whole of one’s life became a fabric, a tapestry with a pattern? She could not see the pattern yet.

tea was opium to them both, the time when the past became a soft pleasant country of the imagination, lost its bitterness, ceased to devour, and in some tea-inspired way nourished them.

Part II felt to me like a strange swerve into the story of Mark Taylor, an aspiring English writer who falls in love with a married painter named Georgia Manning. Their flirtation, as soon through the eyes of a young romantic like Mark, is monolithic, earth-shattering, but to readers is more of a clichéd subplot. In the meantime, Mark sticks to his vow of going on a pilgrimage to Belgium to meet Jean Latour, the poet whose work first inspired him. Part III brings the two strands together in an unexpected way, as Mark gains clarity about his hero and his potential future with Georgia, though cleverer readers than I may have been able to predict it – especially if they heeded the Brontë connection.

It was rewarding to spot the seeds of future Sarton themes here, such as discovering the vocation of teaching (The Small Room) and young people meeting their elder role models and soliciting words of wisdom on how to live (Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing). Through Doro, Sarton also expresses trust in poetry’s serendipitous power. “This is why one is a poet, so that some day, sooner or later, one can say the right thing to the right person at the right time.” I enjoyed my time with the Little Owls but mostly viewed this as a dress rehearsal for later, more mature work. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

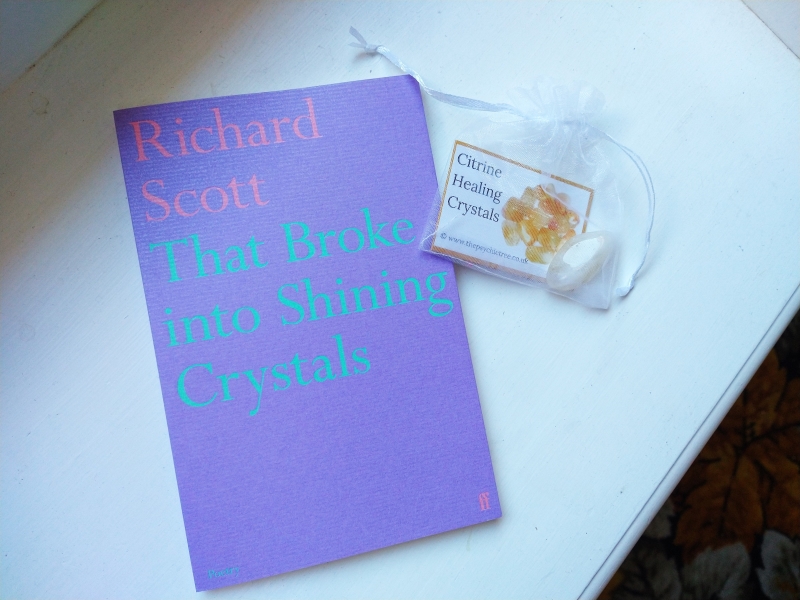

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

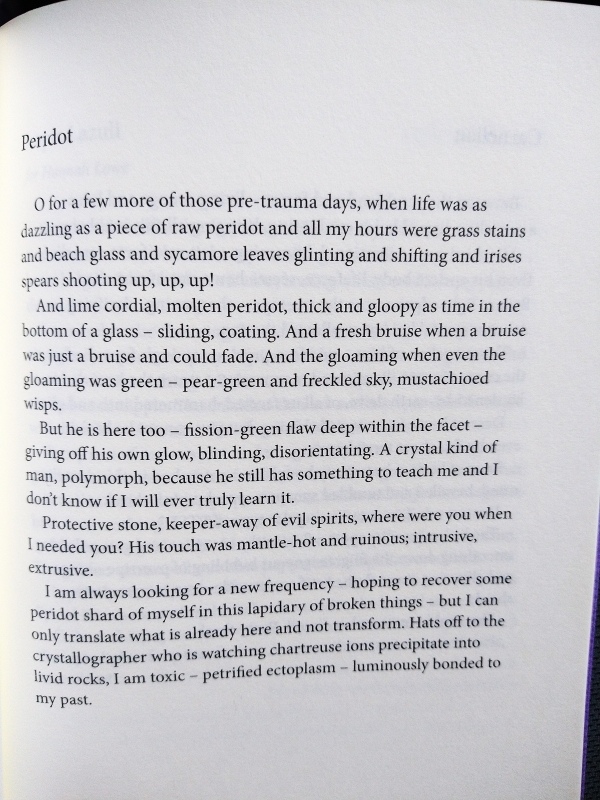

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

Reading Wales Month: Tishani Doshi & Ruth Janette Ruck (#ReadingWales25)

It’s my first time participating in Reading Wales Month, hosted this year by Karen of BookerTalk. I happened to be reading a collection by a Welsh-Gujarati poet, and added a Welsh hill farming memoir to my stack so I could review two books towards this challenge.

A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi (2021)

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

In defiance of those who would destroy it, Doshi affirms the primacy of the body. The joyfully absurd “In a Dream I Give Birth to a Sumo Wrestler” ends with the lines “How easy to forget / that all we have are these bodies. That all of this, all of this is holy.” Poems are inspired by Emily Dickinson and Frida Kahlo as well as by real events that provoke outrage. The clever folktale-like pair “Microeconomics” and “Macroeconomics” contrasts a woman dutifully growing peas and trying to get ahead with exploitative situations: “One man sits on another if he can. … One man goes / into the mines for another man to sparkle.” I also found many wise words on grief. Doshi is a treasure. (Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

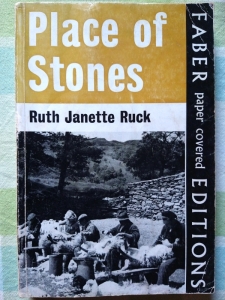

Place of Stones by Ruth Janette Ruck (1961)

“Farming is rather like the theatre—whatever happens the show must go on.”

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

Even when things were going well, it was a hand-to-mouth existence and storms or illness could set everything back. The Rucks renovated a nearby cottage to serve as a holiday let. Another windfall came in the bizarre form of a nearby film shoot by Twentieth Century Fox (The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman). Mountainous North Wales stood in for China, and the film crew hired Ruck as a driver and, like many locals, as an occasional extra. This book was light and mildly entertaining, though probably more detailed about everyday farm work and projects than I needed. I was reminded again of Doreen Tovey, especially in the passage about Topsy the pet black sheep, but also this time of Betty Macdonald (The Egg and I) and Janet White (The Sheep Stell). (Secondhand – Lions bookshop, Alnwick) ![]()

Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

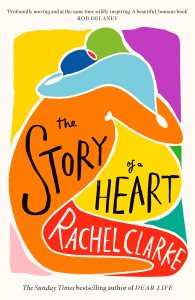

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

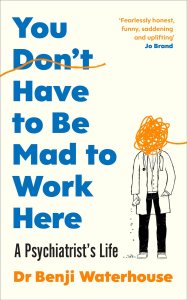

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

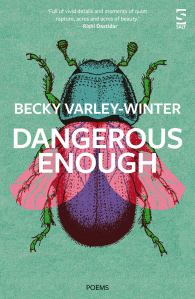

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Three on a Theme: Trans Poetry for National Poetry Day

Today is National Poetry Day here in the UK. Alfie and I spent part of the chilly early morning reading from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s super Poetry Unbound, an anthology of 50 poems to which he’s devoted personal introductions and exploratory essays. He describes poetry as “like a flame: helping us find our way, keeping us warm.”

Poetry Unbound is also the name of his popular podcast; both were recommended to me by Sara Beth West, my fellow Shelf Awareness reviewer, in this interview we collaborated on back in April (National Poetry Month in the USA) about reading and reviewing poetry. I’ve been a keen reader of contemporary poetry for 15 years or so, but in the 3.5 years that I’ve been writing for Shelf I’ve really ramped up. Most months, I review a couple poetry collections for that site, and another one or more on here.

Two of my Shelf poetry reviews from the past 10 months highlight the trans experience; when I recently happened to read another collection by a trans woman, I decided to gather them together as a trio. All three pair the personal – a wrestling over identity – with the political, voicing protest at mistreatment.

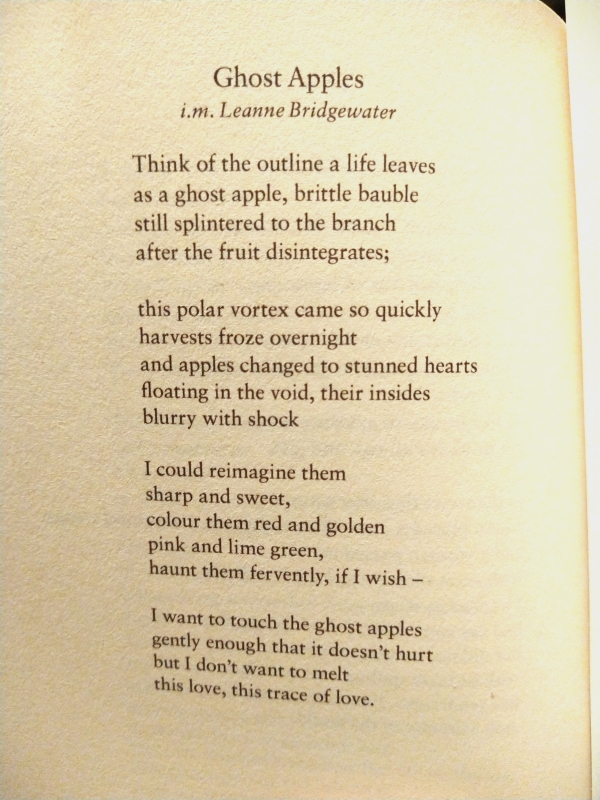

Transitory by Subhaga Crystal Bacon (2023)

In her Isabella Gardner Award-winning fourth collection, queer poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon commemorates the 46 trans and gender-nonconforming people murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020—an “epidemic of violence” that coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The statistics Bacon conveys are heartbreaking: “The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years of age”; “Half of Black trans women spend time in jail”; “Trans people are anywhere/ between eleven and forty percent/ of the homeless population.” She also draws on her own experience of gender nonconformity: “A little butch./ A little femme.” She recalls of visiting drag bars in the 1980s: “We were all/ trying on gender.” And she vows: “No one can say a life is not right./ I have room for you in me.” Her poetic memorial is a valuable exercise in empathy.

Published by BOA Editions. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I was interested to note that the below poets initially published under both female and male, new and dead names, as shown on the book covers. However, a look at social media makes it clear that the trans women are now going exclusively by female names.

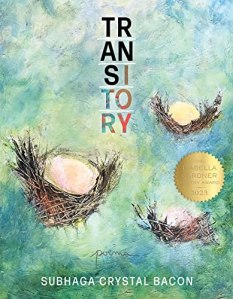

I Don’t Want to Be Understood by Jennifer Espinoza (2024)

In Espinoza’s undaunted fourth poetry collection, transgender identity allows for reinvention but also entails fear of physical and legislative violence.

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Words build into stanzas, prose paragraphs, a zigzag line, or cross-hatching. Espinoza likens the body to a vessel for traumatic memories: “time is a body full of damage// that is constantly trying to forget.” Alliteration and repetition construct litanies of rejection but, ultimately, of hope: “When I call myself a woman I am praying.”

Published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

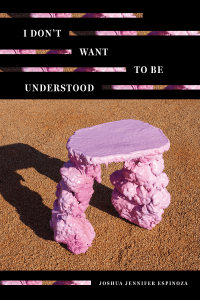

Transgenesis by Ava Winter (2024)

“The body is holy / and is made holy in its changing.”

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Let me greet now,

with warm embrace,

the small blue tablets

I place beneath my tongue each morning.

Oh estradiol,

daily reminder

of what our bodies

have always known:

the many forms of beauty that might be made

flesh by desire, by chance, by animal action.

(from “Transgenesis”)

The first time I wore a dress in public without a hint of irony—a Max Mara wrap adorned with Japanese lilies that framed my shoulders perfectly—I was still thin but also thickly bearded and men on the train whispered to me in a conspiratorial tone, as if they hoped the dress were a joke I might let them in on.

(from “WWII SS Wiking Division Badge, $55”)

– and faith grants affirmation that “there is beauty in such queer and fruitless bodies,” as the title poem insists, with reference to the saris (nonbinary person) acknowledged by the Talmudic rabbis. “Lament with Cello Accompaniment” provides an achingly gorgeous end to the collection:

I do not choose the sound of the song

In my mouth, the fading taste of what I still live through, but I choose this future, as I bury a name defined by grief, as I enter the silence where my voice will take shape.

Winter teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I’ll look out for more of her work.

Published by Milkweed Editions. (Read via Edelweiss)

More trans poetry I have read:

A Kingdom of Love & Eleanor Among the Saints by Rachel Mann

By nonbinary/gender-nonconforming poets, I have also read:

Surge by Jay Bernard

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest

Binded by H Warren

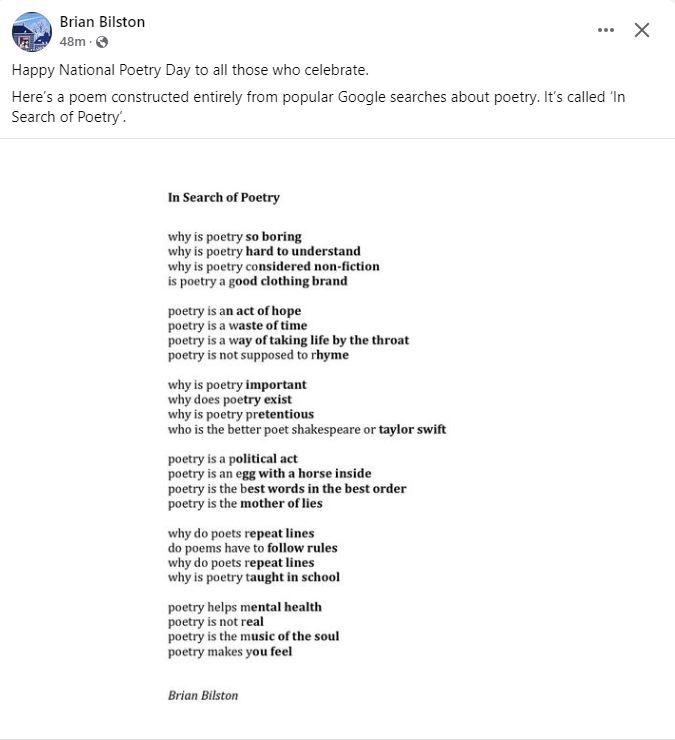

Extra goodies for National Poetry Day:

Follow Brian Bilston to add a bit of joy to your feed.

Editor Rosie Storey Hilton announces a poetry anthology Saraband are going to be releasing later this month, Green Verse: Poems for our Planet. I’ll hope to review it soon.

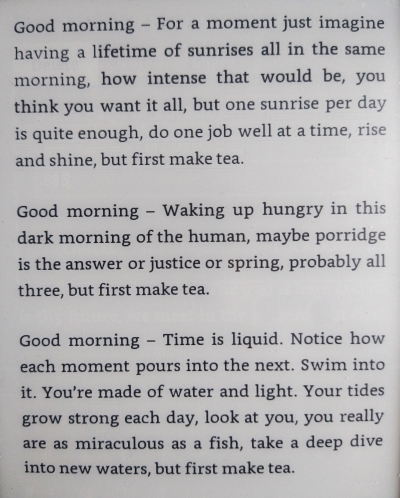

Two poems that have been taking the top of my head off recently (in Emily Dickinson’s phrasing), from Poetry Unbound (left) and Seamus Heaney’s Field Work:

Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

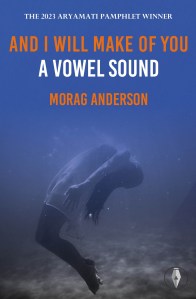

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

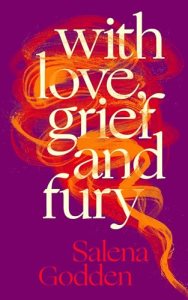

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

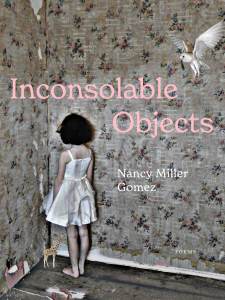

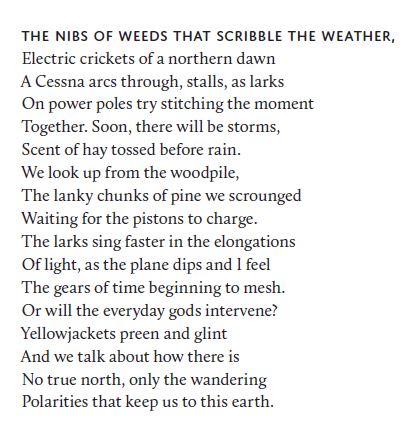

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

With thanks to Alice James Books for the e-copy for review.

From Base Materials by Jenny Lewis

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

“On Translation”

The trouble with translating, for me, is that

when I’ve finished, my own words won’t come;

like unloved step-children in a second marriage,

they hang back at table, knowing their place.

While their favoured siblings hold forth, take

centre stage, mine remain faint, out of ear-shot

like Miranda on her island shore before the boats

came near enough, signalling a lost language;

and always the boom of another surf – pounding,

subterranean, masculine, urgent – makes my words

dither and flit, become little and scattered

like flickering shoals caught up in the slipstream

of a whale, small as sand crabs at the bottom of a bucket,

harmless; transparent as zooplankton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

“Holy”

The days lengthen, the sky quickens.

Something invisible flows in the sticks

and they blossom. We learn to let this

be enough. It isn’t; it’s enough to go on.

Then a lull and a clip on my phone

of a small girl playing with a tennis ball

her three-year-old face a chalice brimming

with life, and I promise when all this is over

I will remember what is holy. I will say

the word without shame, and ask if God

was his own fable to help us bear absence,

the cold space at the heart of the atom.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

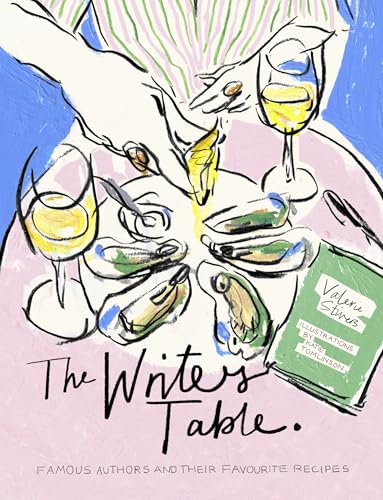

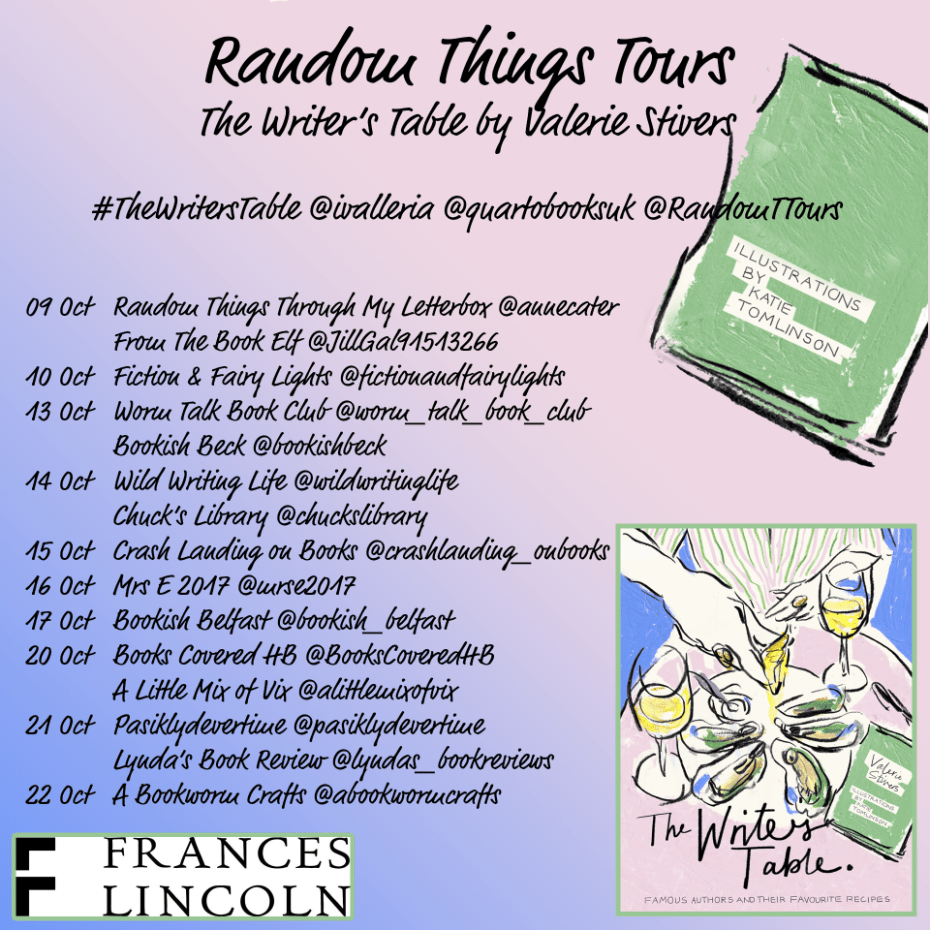

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

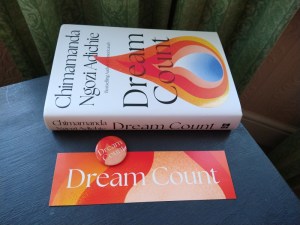

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie