Three on a Theme for Father’s Day: Holt Poetry, Filgate & Virago Anthologies

A rare second post in a day for me; I got behind with my planned cat book reviews. I happen to have had a couple of fatherhood-themed books come my way earlier this year, an essay anthology and a debut poetry collection. To make it a trio, I finished an anthology of autobiographical essays about father–daughter relationships that I’d started last year.

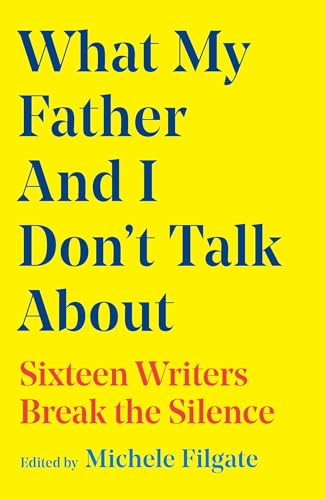

What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, ed. Michele Filgate (2025)

This follow-up to Michele Filgate’s What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About is an anthology of 16 compassionate, nuanced essays probing the intricacies of family relationships.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Some take the title brief literally: Heather Sellers dares to ask her father about his cross-dressing when she visits him in a nursing home; Nayomi Munaweera is pleased her 82-year-old father can escape his arranged marriage, but the domestic violence that went on in it remains unspoken. Tomás Q. Morín’s “Operation” has the most original structure, with the board game’s body parts serving as headings. All the essays display psychological insight, but Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s—contrasting their father’s once-controlling nature with his elderly vulnerability—is the pinnacle.

Despite the heavy topics—estrangement, illness, emotional detachment—these candid pieces thrill with their variety and their resonant themes. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness. (The above is my unedited version.)

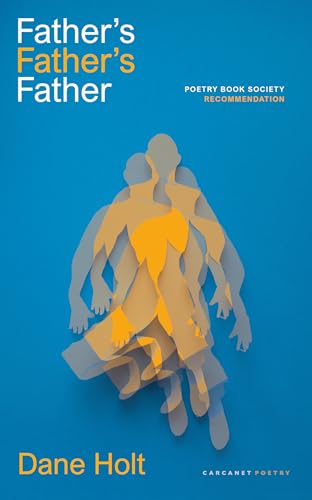

Father’s Father’s Father by Dane Holt (2025)

Holt’s debut collection interrogates masculinity through poems about bodybuilders and professional wrestlers, teenage risk-taking and family misdemeanours.

Your father’s father’s father

poisoned a beautiful horse,

that’s the story. Now you know this

you’ve opened the door marked

‘Family History’.

(from “‘The Granaries are Bursting with Meal’”)

The only records found in my grandmother’s attic

were by scorned women for scorned women

written by men.

(from “Tammy Wynette”)

He writes in the wake of the deaths of his parents, which, as W.S. Merwin observed, makes one feel, “I could do anything,” – though here the poet concludes, “The answer can be nothing.” Stylistically, the collection is more various than cohesive, with some of the late poetry as absurdist as you find in Caroline Bird’s. My favourite poem is “Humphrey Bogart,” with its vision of male toughness reinforced by previous generations’ emotional repression:

My grandfather

never told his son that he loved him.

I said this to a group of strangers

and then said, Consider this:

his son never asked to be told.

They both loved

the men Humphrey Bogart played.

…

There was

one thing my grandfather could

not forgive his son for.

Eventually it was his son’s dying, yes.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen (1983; 1994)

“I doubt if my father will ever lose his power to wound me, and yet…”

~Eileen Fairweather

I read the introduction and first seven pieces (one of them a retelling of a fairy tale) last year and reviewed that first batch here. Some common elements I noted in those were service in a world war, Freudian interpretation, and the alignment of the father with God. The writers often depicted their fathers as unknown, aloof, or as disciplinarians. In the remainder of the book, I particularly noted differences in generations and class. Father and daughter are often separated by 40–55 years. The men work in industry; their daughters turn to academia. Her embrace of radicalism or feminism can alienate a man of conservative mores.

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

I mostly skipped over the quotes from novels and academic works printed between the essays. There are solid pieces by Adrienne Rich, Michèle Roberts, Sheila Rowbotham, and Alice Walker, but Alice Munro knocks all the other contributors into a cocked hat with “Working for a Living,” which is as detailed and psychologically incisive as one of her stories (cf. The Beggar Maid with its urban/rural class divide). Her parents owned a fox farm but, as it failed, her father took a job as night watchman at a factory. She didn’t realize, until one day when she went in person to deliver a message, that he was a janitor there as well.

This was a rewarding collection to read and I will keep it around for models of autobiographical writing, but it now feels like a period piece: the fact that so many of the fathers had lived through the world wars, I think, might account for their cold and withdrawn nature – they were damaged, times were tough, and they believed they had to be an authority figure. Things have changed, somewhat, as the Filgate anthology reflects, though father issues will no doubt always be with us. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop)

April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

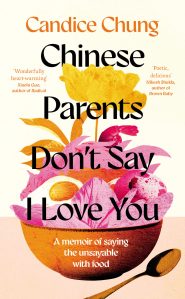

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

April 3rd Releases by Emily Jungmin Yoon & Jean Hannah Edelstein

It’s not often that I manage to review books for their publication date rather than at the end of the month, but these two were so short and readable that I polished them off over the first few days of April. So, out today in the UK: a poetry collection about Asian American identity and environmental threat, and a memoir in miniature about how body parts once sexualized and then functionalized are missed once they’re gone.

Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon (2024)

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

Published in the USA by Knopf on October 22, 2024. With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein

From my Most Anticipated list. I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. This micro-memoir in three essays explores the different roles breasts have played in her life: “Sex” runs from the day she went shopping for her first bra as a teenager with her mother through to her early thirties living in London. Edelstein developed early and eventually wore size DD, which attracted much unwanted attention in social situations and workplaces alike. (And not just a slightly sleazy bar she worked in, but an office, too. Twice she was groped by colleagues; the second time she reported it. But: drunk, Christmas party, no witnesses; no consequences.) “It felt like a punishment, a consequence of my own behavior (being a woman, having a fun night out, doing these things while having large breasts),” she writes.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

Although this is a likable book, the retelling is quite flat; better that than mawkish, certainly, but none of the experiences feel particularly unique. It’s more a generic rundown of what it’s like to be female – which, yes, varies to an extent but not that much if we’re talking about the male gaze. There wasn’t the same spark or wit that I found in Edelstein’s first book. Perhaps in the context of a longer memoir, I would have appreciated these essays more.

With thanks to Phoenix for the free copy for review.

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in  Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters.

Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters. This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle.

This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle. This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages] After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

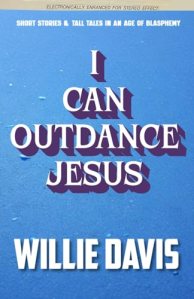

I don’t often take a look at unsolicited review copies, but I couldn’t resist the title of this and I’m glad I gave it a try. Davis’s 10 stories, several of flash length, take place in small-town Kentucky and feature a lovable cast of pranksters, drunks, and spinners of tall tales. The title phrase comes from one of the controversial songs the devil-may-care narrator of “Battle Hymn” writes. My two favourites were “Kid in a Well,” about one-upmanship and storytelling in a local bar, and “The Peddlers,” which has two rogues masquerading as Mormon missionaries. I got vague Denis Johnson vibes from this sassy, gritty but funny collection; Davis is a talent!

I don’t often take a look at unsolicited review copies, but I couldn’t resist the title of this and I’m glad I gave it a try. Davis’s 10 stories, several of flash length, take place in small-town Kentucky and feature a lovable cast of pranksters, drunks, and spinners of tall tales. The title phrase comes from one of the controversial songs the devil-may-care narrator of “Battle Hymn” writes. My two favourites were “Kid in a Well,” about one-upmanship and storytelling in a local bar, and “The Peddlers,” which has two rogues masquerading as Mormon missionaries. I got vague Denis Johnson vibes from this sassy, gritty but funny collection; Davis is a talent! If you’ve read his autobiographical trilogy or seen The Durrells, you’ll be familiar with the quirky, chaotic family atmosphere that reigns in the first two pieces: “The Picnic,” about a luckless excursion in Dorset, and “The Maiden Voyage,” set on a similarly disastrous sailing in Greece (“Basically, the rule in Greece is to expect everything to go wrong and to try to enjoy it whether it does or not”). No doubt there’s some comic exaggeration at work here, especially in “The Public School Education,” about running into a malapropism-prone ex-girlfriend in Venice, and “The Havoc of Havelock,” in which Durrell, like an agony uncle, lends volumes of the sexologist’s work to curious hotel staff in Bournemouth. The final two France-set stories, however, feel like pure fiction even though they involve the factual framing device of hearing a story from a restaurateur or reading a historical manuscript that friends inherited from a French doctor. “The Michelin Man” is a cheeky foodie one with a surprisingly gruesome ending; “The Entrance” is a full-on dose of horror worthy of R.I.P. I wouldn’t say this is essential reading for Durrell fans, but it was a pleasant way of passing the time. (Secondhand – Lions Bookshop, Alnwick, 2021)

If you’ve read his autobiographical trilogy or seen The Durrells, you’ll be familiar with the quirky, chaotic family atmosphere that reigns in the first two pieces: “The Picnic,” about a luckless excursion in Dorset, and “The Maiden Voyage,” set on a similarly disastrous sailing in Greece (“Basically, the rule in Greece is to expect everything to go wrong and to try to enjoy it whether it does or not”). No doubt there’s some comic exaggeration at work here, especially in “The Public School Education,” about running into a malapropism-prone ex-girlfriend in Venice, and “The Havoc of Havelock,” in which Durrell, like an agony uncle, lends volumes of the sexologist’s work to curious hotel staff in Bournemouth. The final two France-set stories, however, feel like pure fiction even though they involve the factual framing device of hearing a story from a restaurateur or reading a historical manuscript that friends inherited from a French doctor. “The Michelin Man” is a cheeky foodie one with a surprisingly gruesome ending; “The Entrance” is a full-on dose of horror worthy of R.I.P. I wouldn’t say this is essential reading for Durrell fans, but it was a pleasant way of passing the time. (Secondhand – Lions Bookshop, Alnwick, 2021) Three suites of linked stories focus on young women whose choices in the 1980s have ramifications decades later. Chance meetings, addictions, ill-considered affairs, and random events all take their toll. Emma house-sits and waitresses while hoping in vain for her acting career to take off; “all she felt was a low-grade mourning for what she’d lost and hadn’t attained.” My favourite pair was about Nina, who is a photographer’s assistant in “Single Lens Reflex” and 13 years later, in “Photo Finish,” bumps into the photographer again in Central Park. With wistful character studies and nostalgic snapshots of changing cities, this is a stylish and accomplished collection.

Three suites of linked stories focus on young women whose choices in the 1980s have ramifications decades later. Chance meetings, addictions, ill-considered affairs, and random events all take their toll. Emma house-sits and waitresses while hoping in vain for her acting career to take off; “all she felt was a low-grade mourning for what she’d lost and hadn’t attained.” My favourite pair was about Nina, who is a photographer’s assistant in “Single Lens Reflex” and 13 years later, in “Photo Finish,” bumps into the photographer again in Central Park. With wistful character studies and nostalgic snapshots of changing cities, this is a stylish and accomplished collection. The first section contains nine linked stories about a group of five elderly female friends. Bessie jokes that “wakes and funerals are the cocktail parties of the old,” and Ruth indeed mistakes a shivah for a party and meets a potential beau who never quite successfully invites her on a date. One of their members leaves the City for a nursing home; “Sans Teeth, Sans Taste” is a good example of the morbid sense of humour. A few unrelated stories draw on Segal’s experience being evacuated from Vienna to London by Kindertransport; “Pneumonia Chronicles” is one of several autobiographical essays that bring events right up to the Covid era – closing with the bonus story “Ladies’ Zoom.” The ladies’ stories are quite amusing, but the book as a whole feels like an assortment of minor scraps; it was published when Segal, a New Yorker contributor, was 95. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop, 2023)

The first section contains nine linked stories about a group of five elderly female friends. Bessie jokes that “wakes and funerals are the cocktail parties of the old,” and Ruth indeed mistakes a shivah for a party and meets a potential beau who never quite successfully invites her on a date. One of their members leaves the City for a nursing home; “Sans Teeth, Sans Taste” is a good example of the morbid sense of humour. A few unrelated stories draw on Segal’s experience being evacuated from Vienna to London by Kindertransport; “Pneumonia Chronicles” is one of several autobiographical essays that bring events right up to the Covid era – closing with the bonus story “Ladies’ Zoom.” The ladies’ stories are quite amusing, but the book as a whole feels like an assortment of minor scraps; it was published when Segal, a New Yorker contributor, was 95. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop, 2023)