Victorian-Themed Novels by Annie Elliot and Livi Michael (#ReadIndies)

I’m going back to my roots as a Victorianist (I completed an MA in Victorian Literature at the University of Leeds in 2006) with these two new novels, the one about Charles Dickens’s turbulent marriage and the other about the real-life inspiration for Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth. Both redress the balance of Victorian literature by placing women at the centre of the action, and both were comfortably in the 200–300-page range: turns out that’s how I like my Victoriana these days; none of your triple-decker nonsense.

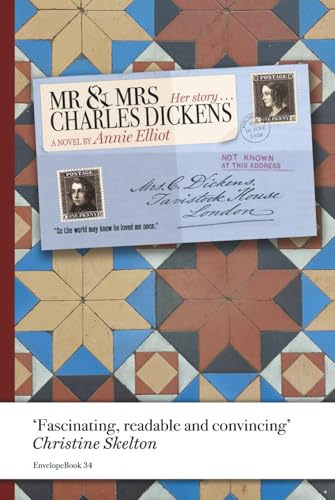

Mr & Mrs Charles Dickens: Her Story by Annie Elliot

I used to proclaim Dickens my favourite author yet haven’t managed to read one of his novels in 15+ years; I seem to be allergic to all that verbiage. He managed to write all those millions of words thanks to his increasing status and wealth, but also thanks to his long-suffering wife, Catherine. Kate sacrificed her health and ambitions to bear and raise his nine children (along with one who died) and – along with sisters and servants – keep a house calm and quiet enough to enable his work.

On her deathbed, Kate begged her daughter to give her love letters from Charles to the British Museum “so the world may know he loved me once.” Annie Elliot has used that phrase as the tagline for her absorbing and vigilantly researched debut novel. The structure perfectly mimics romantic illusions ceding to disenchantment. The framing story is set on 10 June 1870 – the day Kate, the estranged wife, learns of Charles’s death. Sections alternate between the bereaved Kate’s fragile state of mind (depicted in the third person) and first-person flashbacks to their relationship, from first meeting in 1834 to infamous separation in 1858.

On her deathbed, Kate begged her daughter to give her love letters from Charles to the British Museum “so the world may know he loved me once.” Annie Elliot has used that phrase as the tagline for her absorbing and vigilantly researched debut novel. The structure perfectly mimics romantic illusions ceding to disenchantment. The framing story is set on 10 June 1870 – the day Kate, the estranged wife, learns of Charles’s death. Sections alternate between the bereaved Kate’s fragile state of mind (depicted in the third person) and first-person flashbacks to their relationship, from first meeting in 1834 to infamous separation in 1858.

It’s all narrated in the present tense, which creates an eternal now: nothing can be dated when it’s all happening at once for Kate. To start with, the Dickens marriage seems to be based on real love and physical passion. But before long it’s clear that he’s using Kate as ego boost and sexual outlet. She walks on eggshells lest anything shake his confidence. While the death of their baby daughter Dora nearly breaks her, he keeps up a frenzy of writing, travel, property acquisition, and new ventures such as public speaking and the theatre. And, of course, it’s through dramatics that he meets young Nelly Ternan and finds his excuse to push Kate aside.

Though much of this material was familiar to me from Claire Tomalin’s biographies as well as Gaynor Arnold’s novel about Kate, Girl in a Blue Dress, I appreciated the recreation of Kate’s perspective, the glimpses of their children’s lives, and the flashes of humour such as the proliferation of Pickwick memorabilia and a visit from Hans Christian Andersen. This is – yes, still – a necessary corrective to Dickens’s image as the dutiful husband and paterfamilias. And such a beautifully presented book, too. I wish Elliot well for next year’s McKitterick Prize race.

To be published on 1 March. With thanks to the author and EnvelopeBooks for the free copy for review.

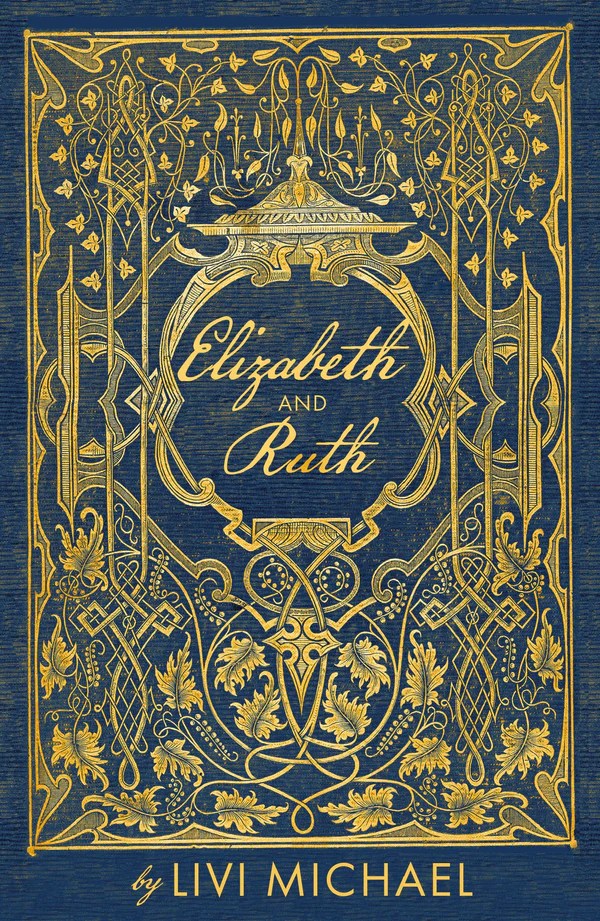

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael

The Manchester of 1849 is a sordid complex of sweatshops, brothels and workhouses – if you’re Pasley, an Irish teenager abandoned by her mother and shunted from one bad situation to another. Or the Manchester of 1849 is a rarefied colloquium of forward-thinking authors, ministers and politicians – if you’re Elizabeth Gaskell, who’s been revealed as the mind behind the anonymously published sensation Mary Barton.

The two worlds collide when Elizabeth visits Pasley at the New Bailey Prison. She feels for this young woman who’s been a victim of deception, trafficking, and rape and narrowly escaped death by suicide only to end up imprisoned for theft when she made a desperate bid for freedom. There’s only so much that Pasley can bear to tell Mrs Gaskell on these short visits, though; her past would shock a preacher’s wife. Through euphemisms and evasions, Pasley is able to convey that she was taken advantage of by a doctor. Elizabeth suspects that there was a baby, but only readers know the whole truth.

Chapters alternate between Elizabeth’s experience – in an omniscient third person cleverly reminiscent of Victorian prose – and Pasley’s first-person recollections. Elizabeth wants to follow through on her do-gooder reputation and truly help Pasley, who reminds her of her own infant and pregnancy losses. Achieving justice for the girl would be a bonus. All she knows to do is use her pen to change hearts and minds, as she has before (including for Dickens’s magazine) to draw attention to the plight of the poor. Thus, Ruth was born.

This is a riveting and touching novel about the rigidity of convention and the limits of compassion. Livi Michael is a prolific author of whom I’d not heard before Salt sent me this surprise, perfectly suited parcel. Her vivid scenes bring the two-tiered Manchester society to life and reminded me of my visit to the Gaskell House in 2015. My only small complaint would be that the blurb makes it sound as if Gaskell’s correspondence with Dickens will be a central element, when in fact it only appears once, two-thirds of the way through, with one cameo appearance by Dickens right at the end. He’s the better-known author, but after reading this you’ll agree that Gaskell was the subtler, more elegant chronicler.

Published on 9 February. With thanks to Salt Publishing for the proof copy for review.

#ReadIndies Review Catch-Up: Chevillard, Hopkins & Bateman, McGrath, Richardson

Quick thoughts on some more review catch-up books, most of them from 2025. It’s a miscellaneous selection today: absurdist flash fiction by a prolific French author, a self-help graphic novel about surviving heartbreak, a blend of bird photography and poetry, and a debut poetry collection about life and death as encountered by a parish priest.

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard (2024)

[Trans. from French by David Levin Becker]

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

With thanks to the University of Yale Press for the free copy for review.

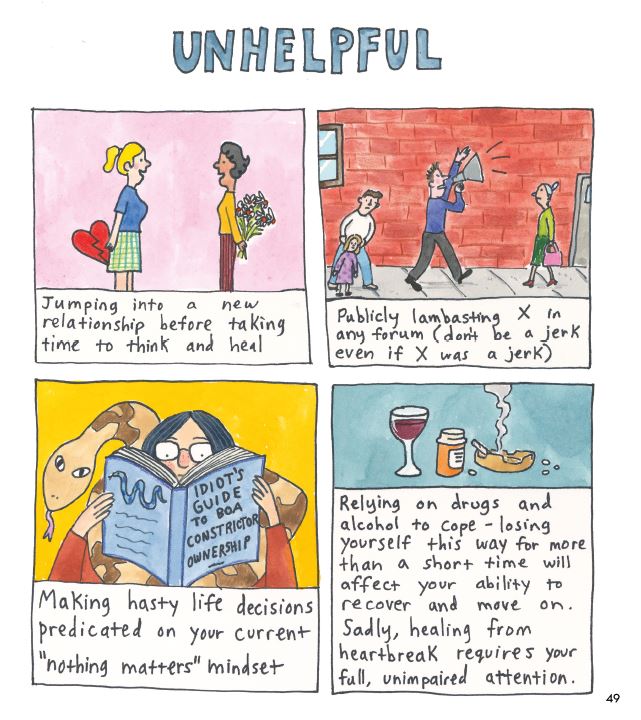

What to Do When You Get Dumped: A Guide to Unbreaking Your Heart by Suzy Hopkins; illus. Hallie Bateman (2025)

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free e-copy for review.

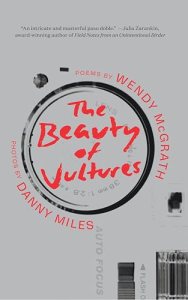

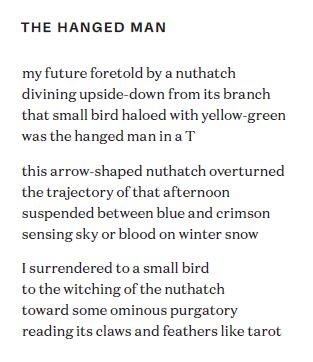

The Beauty of Vultures by Wendy McGrath; photos by Danny Miles (2025)

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

Other poems describe birds, address them directly, or take on their perspectives. Birds are a reassuring presence (cf. Ted Hughes on swifts): “I counted on our robins to return every spring” as a balm, the anxious speaker reports in “Air raid siren.” A nest of gape-mouthed baby swallows in an outhouse is the prize at the end of a long countryside walk. With its alliteration and repetition, “The Goldfinch Charm” feels like an incantation. Birds model grace (or at least the appearance of grace):

Assume a buoyancy, lightness, as though you were about to fly.

That yellow rubber duck is my surreal mythology.

Head above water. Stay calm. Paddle like crazy.

They link the natural world and the human in these gorgeous poems that interact with the images in ways that both lead and illuminate.

A female swan is a pen and eyes open

I try to write this dream:

a moment stolen or given.

Published by NeWest Press. With thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review.

Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson (2026)

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

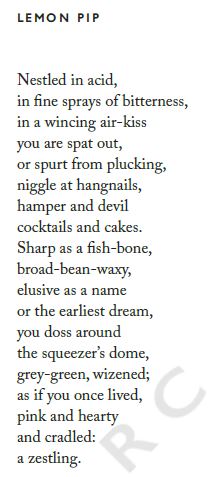

#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

The Moomins and the Great Flood (#Moomins80) & Poetry (#ReadIndies)

To mark the 80th anniversary of Tove Jansson’s Moomins books, Kaggsy, Liz et al. are doing a readalong of the whole series, starting with The Moomins and the Great Flood. I received a copy of Sort Of Books’ 2024 reissue edition for Christmas, so I was unknowingly all set to take part. I also give quick responses to a couple of collections I read recently from two favourite indie poetry publishers in the UK, The Emma Press and Carcanet Press. These are reads 9–11 for Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge.

The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson (1945; 1991)

[Translated from the Swedish by David McDuff]

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

I read my first Moomins tale in 2011 and have been reading them out of order and at random ever since; only one remains unread. Unfortunately, I did not find it rewarding to go right back to the beginning. At barely 50 pages (padded out by the Cottrell-Boyce introduction and an appendix of Jansson’s who’s-who notes), this story feels scant, offering little more than a hint of the delightful recurring characters and themes to come. Jansson had not yet given the Moomins their trademark rounded hippo-like snouts; they’re more alien and less cute here. It’s like seeing early Jim Henson drawings of Garfield before he was a fat cat. That just ain’t right. I don’t know why I’d assumed the Moomins are human-size. When you see one next to a marabou stork you realize how tiny they are; Jansson’s notes specify 20 cm tall. (Gift)

The Emma Press Anthology of Homesickness and Exile, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

Departures, arrivals; longing, regret: these are classic themes from Ovid (the inspiration for this volume) onward. Holly Hopkins and Rachel Long were additional familiar names for me to see in the table of contents. My two favourite poems were “The Restaurant at One Thousand Feet” (about the CN Tower in Toronto) by John McCullough, whose collections I’ve enjoyed before; and “The Town” by Alex Bell, which personifies a closed-minded Dorset community – “The town wraps me tight as swaddling … When I came to the town I brought things with me / from outside, and the town took them / for my own good.” Home is complicated – something one might spend an entire life searching for, or trying to escape. (New purchase from publisher)

Gold by Elaine Feinstein (2000)

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I wanted to live with a bit of flash and brio,

rather than huddle behind ghetto gates.

The last two stanzas are especially memorable:

Poor Mozart was so much less fortunate.

My only sadness is to think of him, a pauper,

lying in his grave, while I became

Professor of Italian literature.

Nobody living can predict their fate.

I moved across the cusp of a new age,

to reach this present hour of privilege.

On this earth, luck is worth more than gold.

Politics, manners, morals all evolve

uncertainly. Best then to be bold.

Best then to be bold!

Of the discrete “Lyrics” that follow, I most liked “Options,” about a former fiancé (“who can tell how long we would have / burned together, before turning to ash?”) and “Snowdonia,” in which she’s surprised when a memory of her father resurfaces through a photograph. Talking to the Dead was more consistently engaging. (Secondhand purchase – Bridport Old Books, 2023)

Winter Reads, I: Michael Cunningham & Helen Moat

It’s been feeling springlike in southern England with plenty of birdsong and flowers, yet cold weather keeps making periodic returns. (For my next instalment of wintry reads, I’ll try to attract some snow to match the snowdrops by reading three “Snow” books.) Today I have a novel drawing on a melancholy Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale and a nature/travel book about learning to appreciate winter.

The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham (2014)

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

Of course, Cunningham takes inspiration, thematically and linguistically, from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale about love and conversion, most obviously in an early dreamlike passage about Tyler letting snow swirl into the apartment through the open windows:

He returns to the window. If that windblown ice crystal meant to weld itself to his eye, the transformation is already complete; he can see more clearly now with the aid of this minuscule magnifying mirror…

I was most captivated by the early chapters of the novel, picking it up late one night and racing to page 75, which is almost unheard of for me. The rest took me significantly longer to get through, and in the intervening five weeks or so much of the detail has evaporated. But I remember that I got Chris Adrian and Julia Glass vibes from the plot and loved the showy prose. (And several times while reading I remarked to people around me how ironic it was that these characters in a 2014 novel are so outraged about Dubya’s re-election. Just you all wait two years, and then another eight!)

I fancy going on a mini Cunningham binge this year. I plan to recommend The Hours for book club, which would be a reread for me. Otherwise, I’ve only read his travel book, Land’s End. I own a copy of Specimen Days and the library has Day, but I’d have to source all the rest secondhand. Simon of Stuck in a Book is a big fan and here are his rankings. I have some great stuff ahead! (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

While the Earth Holds Its Breath: Embracing the Winter Season by Helen Moat (2024)

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

There were many incidents and emotions I could relate to here – a walk on the canal towpath always makes me feel better, and the car-heavy lifestyle I resume on trips to America feels unnatural.

Days are where we must live, but it didn’t have to be a prison of house and walls. I needed the rush of air, the slap of wind on my cheeks. I needed to feel alive. Outdoors.

I’d never liked the rain, but if I were to grow to love winters on my island, I had to learn to love wet weather, go out in it.

What can there be but winter? It belongs to the circle of life. And I belonged to winter, whether I liked it or not. Indoors, or moving from house to vehicle and back to house again, I lost all sense of my place on this Earth. This world would be my home for just the smallest of moments in the vastness of time, in the turning of the seasons. It was a privilege, I realised.

However, the content is repetitive such that the three-year cycle doesn’t add a lot and the same sorts of pat sentences about learning to love winter recur. Were the timeline condensed, there might have been more of a focus on the more interesting travel segments, which also include France and Scotland. So many have jumped on the Wintering bandwagon, but Katherine May’s book felt fresh in a way the others haven’t.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

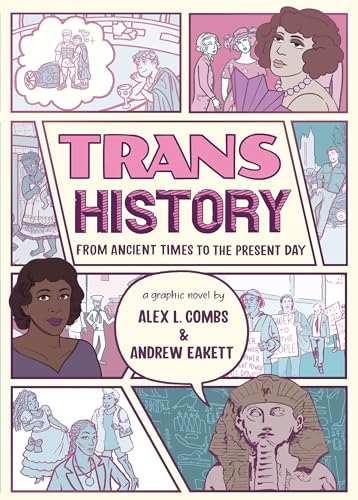

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research. The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint.

The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint. Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride.

Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride. As I found when I

As I found when I  I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world. Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my

Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my  Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of  That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s. Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus. If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma. The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection. Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.) I’ve also read Watts’

I’ve also read Watts’