Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

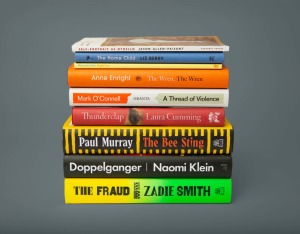

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Review Book Catch-Up: Motherhood, Nature Essays, Pandemic, Poetry

July slipped away without me managing to review any current-month releases, as I am wont to do, so to those three I’m adding in a couple of other belated review books to make up today’s roundup. I have: a memoir-cum-sociological study of motherhood, poems of Afghan women’s experiences, a graphic novel about a fictional worst-case pandemic, seasonal nature essays from voices not often heard, and poetry about homosexual encounters.

(M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman by Pragya Agarwal

“Mothering would be my biggest gesture of defiance.”

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Married and unexpectedly pregnant in 1996, Agarwal determined to raise her daughter differently. Her mother-in-law was deeply disappointed that the baby was a girl, which only increased her stubborn pride: “Giving birth to my daughter felt like first love, my only love. Not planned but wanted all along. … Me and her against the world.” No element of becoming a mother or of her later life lived up to her expectations, but each apparent failure gave a chance to explore the spectrum of women’s experiences: C-section birth, abortion, divorce, emigration, infertility treatment, and finally having further children via a surrogate.

While I enjoyed the surprising sweep of Agarwal’s life story, this is no straightforward memoir. It aims to be an exhaustive survey of women’s life choices and the cultural forces that guide or constrain them. The book is dense with history and statistics, veers between topics, and needed a better edit for vernacular English and smoothing out academic jargon. I also found that I wasn’t interested enough in the specifics of women’s lives in India.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Forty Names by Parwana Fayyaz

“History has ungraciously failed the women of my family”

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Fayyaz is bold to speak out about the injustices women can suffer in Afghan culture. Domestic violence is rife; miscarriage is considered a disgrace. In “Roqeeya,” she remembers that her mother, even when busy managing a household, always took time for herself and encouraged Parwana, her eldest, to pursue an education and earn her own income. However, the poet also honours the wisdom and skills that her illiterate mother exhibited, as in the first three poems about the care she took over making dresses and dolls for her three daughters.

As in Agarwal’s book, there is a lot here about ideals of femininity and the different routes that women take – whether more or less conventional. “Reading Nadia with Eavan” was a favourite for how it brought together different aspects of Fayyaz’s experience. Nadia Anjuman, an Afghan poet, was killed by her husband in 2005; many years later, Fayyaz found herself studying Anjuman’s work at Cambridge with the late Eavan Boland. Important as its themes are, I thought the book slightly repetitive and unsubtle, and noted few lines or turns of phrase – always a must for me when assessing a poetry collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Resistance by Val McDermid; illus. Kathryn Briggs

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

Zoe Beck, a Black freelance journalist who conducted interviews at Solstice, is friends with Sam and starts investigating the mutated swine disease, caused by an Erysipelas bacterium and thus nicknamed “the Sips.” She talks to the festival doctor and to a female Muslim researcher from the Life Sciences Centre in Newcastle, but her search for answers takes a backseat to survival when her husband and sons fall ill.

The drawing style and image quality – some panes are blurry, as if badly photocopied – let an otherwise reasonably gripping story down; the best spreads are collages or borrow a frame/backdrop (e.g. a medieval manuscript, NHS forms, or a 1910s title page).

SPOILER

{The ending, which has an immune remnant founding a new community, is VERY Parable of the Sower.}

With thanks to Profile Books/Wellcome Collection for the free copy for review.

Gifts of Gravity and Light: A Nature Almanac for the 21st Century, ed. Anita Roy and Pippa Marland

I hadn’t heard about this upcoming nature anthology when a surprise copy dropped through my letterbox. I’m delighted the publisher thought of me, as this ended up being just my sort of book: 12 autobiographical essays infused with musings on landscapes in Britain and elsewhere; structured by the seasons to create a gentle progression through the year, starting with the spring. Best of all, the contributors are mostly female, BIPOC (and Romany), working class and/or queer – all told, the sort of voices that are heard far too infrequently in UK nature writing. In momentous rites of passage, as in routine days, nature plays a big role.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

Most of the authors hold two places in mind at the same time: for Michael Malay, it’s Indonesia, where he grew up, and the Severn estuary, where he now lives and ponders eels’ journeys; for Zakiya McKenzie, it’s Jamaica and England; for editor Anita Roy, it’s Delhi versus the Somerset field her friend let her wander during lockdown. Trees lend an awareness of time and animals a sense of movement and individuality. Alys Fowler thinks of how the wood she secretly coppices and lays on park paths to combat the mud will long outlive her, disintegrating until it forms the very soil under future generations’ feet.

A favourite passage (from Bradley): “When nature is the cuddly bunny and the friendly old hill, it becomes too easy to dismiss it as a faithful retainer who will never retire. But nature is the panic at the end of a talon, and it’s the tree with a heart of fire where lightning has struck. It is not our friend, and we do not want to make it our enemy.”

Also featured: Bernardine Evaristo (foreword), Raine Geoghegan, Jay Griffiths, Amanda Thomson, and Luke Turner.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Records of an Incitement to Silence by Gregory Woods

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Other times the perspective is omniscient, painting a character study, like “Company” (“When he goes home to bed / he dare not go alone. … This need / of company defeats him.”), or of Frank O’Hara in “Up” (“‘What’s up?’ Frank answers with / his most unseemly grin, / ‘The sun, the Dow, my dick,’ / and saunters back to bed.”). Formalists are sure to enjoy Woods’ use of form, rhyme and meter. I enjoyed some of the book’s cheeky moments but had trouble connecting with its overall tone and content. That meant that it felt endless. I also found the end rhymes, when they did appear, over-the-top and silly (Demeter/teeter, etc.).

Two favourite poems: “An Immigrant” (“He turned away / to strip. His anecdotes / were innocent and his / erection smelled of soap.”) and “A Knot,” written for friends’ wedding in 2014 (“make this wedding supper all the sweeter / With choirs of LGBT cherubim”).

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Recent and Upcoming Poetry Releases from Carcanet Press

Many thanks to the publisher for free print or e-copies of these three books for review.

In Nearby Bushes by Kei Miller

“Are there stories you have heard about Jamaica? / Well here are the stories underneath.” The last two lines of “The Understory” reveal Miller’s purpose in this, his fifth collection of poetry. The title is taken from Jamaican crime reports, which often speak of a victim’s corpse being dumped in, or perpetrators escaping to, “nearby bushes.” It’s a strange euphemism that calls to mind a dispersed underworld where bodies are devalued. Miller persistently contrasts a more concrete sense of place with that iniquitous nowhere. Most of the poems in the first section open with the word “Here,” which is also often included in their titles and repeated frequently throughout Part I. Jamaica is described with shades of green: a fertile, feral place that’s full of surprises, like an escaped colony of reindeer.

“Are there stories you have heard about Jamaica? / Well here are the stories underneath.” The last two lines of “The Understory” reveal Miller’s purpose in this, his fifth collection of poetry. The title is taken from Jamaican crime reports, which often speak of a victim’s corpse being dumped in, or perpetrators escaping to, “nearby bushes.” It’s a strange euphemism that calls to mind a dispersed underworld where bodies are devalued. Miller persistently contrasts a more concrete sense of place with that iniquitous nowhere. Most of the poems in the first section open with the word “Here,” which is also often included in their titles and repeated frequently throughout Part I. Jamaica is described with shades of green: a fertile, feral place that’s full of surprises, like an escaped colony of reindeer.

As usual, Miller slips in and out of dialect as he reflects on the country’s colonial legacy and the precarious place of homosexuals (“A Psalm for Gay Boys” is a highlight). Although I enjoyed this less than the other books I’ve read by Miller, I highly recommend his work in general; the collection The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion is a great place to start.

Some favorite lines:

“Here that cradles the earthquakes; / they pass through the valleys // in waves, a thing like grief, / or groaning that can’t be uttered.” (from “Hush”)

“We are insufficiently imagined people from an insufficiently imagined place.” (from “Sometimes I Consider the Names of Places”)

“Cause woman is disposable as that, / and this thing that has happened is … common as stone and leaf and breadfruit tree. You should have known.” (from “In Nearby Bushes” XIII.III)

My rating:

In Nearby Bushes was published on 29th August.

So Many Rooms by Laura Scott

Art, Greek mythology, the seaside, the work of Tolstoy, death, birds, fish, love and loss: there are lots of repeating themes and images in this debut collection. While there are a handful of end rhymes scattered through, what you mostly notice is alliteration and internal rhyming. The use of color is strong, and not just in the poems about paintings. A few of my favorites were “Mulberry Tree” (“My mother made pudding with its fruit, / white bread drinking / colour just as the sheets waited / for the birds to stain them purple.”), “Direction,” and “A Different Tune” (“oh my heavy heart how can I / make you light again so I don’t have to // lug you through the years and rooms?”). There weren’t loads of poems that stood out to me here, but I’ll still be sure to look out for more of Scott’s work.

Art, Greek mythology, the seaside, the work of Tolstoy, death, birds, fish, love and loss: there are lots of repeating themes and images in this debut collection. While there are a handful of end rhymes scattered through, what you mostly notice is alliteration and internal rhyming. The use of color is strong, and not just in the poems about paintings. A few of my favorites were “Mulberry Tree” (“My mother made pudding with its fruit, / white bread drinking / colour just as the sheets waited / for the birds to stain them purple.”), “Direction,” and “A Different Tune” (“oh my heavy heart how can I / make you light again so I don’t have to // lug you through the years and rooms?”). There weren’t loads of poems that stood out to me here, but I’ll still be sure to look out for more of Scott’s work.

My rating:

So Many Rooms was published on 29th August.

A Kingdom of Love by Rachel Mann

Rachel Mann, a transgender Anglican priest, was Poet-in-Residence at Manchester Cathedral from 2009 to 2017 and is now a Visiting Fellow in Creative Writing and English at Manchester Metropolitan University. Her poetry is full of snippets of scripture and liturgy (both English and Latin), and the cadence is often psalm-like. The final five poems are named after some of the daily offices, and “Christening” and “Extreme Unction” are two stand-outs that describe performing rituals for the beginning and end of life. The poet draws on Greek myth as well as on the language of Christian classics from St. Augustine to R.S. Thomas.

Human fragility is an almost comforting undercurrent (“Be dust with me”), with the body envisioned as the site of both sin and redemption. A focus on words leads to a preoccupation with mouths and the physical act of creating and voicing language. There is surprisingly anatomical vocabulary in places: the larynx, the palate. Mann also muses on Englishness, and revels in the contradictions of ancient and modern life: Chaucer versus a modern housing development, “Reading Ovid on the Underground.” She undertakes a lot of train rides and writes of passing through stations, evoking the feeling of being in transit(ion).

Human fragility is an almost comforting undercurrent (“Be dust with me”), with the body envisioned as the site of both sin and redemption. A focus on words leads to a preoccupation with mouths and the physical act of creating and voicing language. There is surprisingly anatomical vocabulary in places: the larynx, the palate. Mann also muses on Englishness, and revels in the contradictions of ancient and modern life: Chaucer versus a modern housing development, “Reading Ovid on the Underground.” She undertakes a lot of train rides and writes of passing through stations, evoking the feeling of being in transit(ion).

You wouldn’t know the poet had undergone a sex change unless you’d already read about it in the press materials or found other biographical information, but knowing the context one finds extra meaning in “Dress,” about an eight-year-old coveting a red dress (“To simply have known it was mine / in those days”) and “Give It a Name,” about the early moments of healing from surgery.

This is beautiful, incantatory free verse that sparkles with alliteration and allusions that those of a religious background will be sure to recognize. It’s sensual as well as headily intellectual. Doubt, prayer and love fuel many of my favorite lines:

“Love should taste of something, / The sea, I think, brined and unsteady, / Of scale and deep and all we crawled out from.” (from “Collect for Purity”)

“I don’t know what ‘believe in’ means / In the vast majority of cases, / Which is to say I think it enough // To acknowledge glamour of words – / Relic, body, bone – I think / Mystery is laid in syllables, syntax” (from “Fides Quarens”)

“Offer the fact of prayer – a formula, / And more: the compromise of centuries / Made valid.” (from “A Kingdom of Love (2)”)

Particularly recommended for readers of Malcolm Guite and Christian Wiman.

My rating:

Official release date: September 26th – but already available from the Carcanet website.

Any recent poetry reads you’d recommend?

Rathbones Folio Prize Shortlist: The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus

The Rathbones Folio Prize is unique in that nominations come from The Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, and any book written in English is eligible, so there’s nonfiction and poetry as well as fiction on this year’s varied shortlist of eight titles:

Can You Tolerate This? by Ashleigh Young [essays]

Can You Tolerate This? by Ashleigh Young [essays]- The Crossway by Guy Stagg [travel memoir]

- Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly [historical fiction]

- Milkman by Anna Burns [literary fiction]

- Ordinary People by Diana Evans [literary fiction]

- The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus [poetry]

- There There by Tommy Orange [literary fiction]

- West by Carys Davies [historical fiction]

I’m helping to kick off the Prize’s social media tour by championing the debut poetry collection The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus (winner of the 2018 Geoffrey Dearmer Award from the Poetry Society), issued by the London publisher Penned in the Margins last year. Antrobus is a British-Jamaican poet with an MA in Spoken Word Education who has held multiple residencies in London schools and works as a freelance teacher and poet. His poems dwell on the uneasiness of bearing a hybrid identity – he’s biracial and deaf but functional in the hearing world – and reflect on the loss of his father and the intricacies of Deaf history.

I was previously unaware of the difference between “deaf” and “Deaf,” but it’s explained in the book’s endnotes: Deaf refers to those who are born deaf and learn sign before any spoken language, so they tend to consider deafness part of their cultural identity; deaf means that the deafness was acquired later in life and is a medical consequence rather than a defining trait.

The opening poem, “Echo,” recalls how Antrobus’s childhood diagnosis came as a surprise because hearing problems didn’t run in the family.

I sat in saintly silence

during my grandfather’s sermons when he preached

The Good News I only heard

as Babylon’s babbling echoes.

Raymond Antrobus. Photo credit: Caleb Femi.

Nowadays he uses hearing aids and lip reading, but still frets about how much he might be missing, as expressed in the prose poem “I Move through London like a Hotep” (his mishearing when a friend said, “I’m used to London life with no sales tax”). But if he had the choice, would Antrobus reverse his deafness? As he asks himself in one stanza of “Echo,” “Is paradise / a world where / I hear everything?”

Learning how to live between two worlds is a major theme of the collection, applying not just to the Deaf and hearing communities but also to the balancing act of a Black British identity. I first encountered Antrobus through the recent Black British poetry anthology Filigree (I assess it as part of a review essay in an upcoming issue of Wasafiri literary magazine), which reprints his poem “My Mother Remembers.” A major thread in that volume is art as a means of coming to terms with racism and constructing an individual as well as a group identity. The ghazal “Jamaican British” is the clearest articulation of that fight for selfhood, reinforced by later poems on being called a foreigner and harassment by security staff at Miami airport.

The title comes from the name of the pub where Antrobus’s father drank while his son waited outside. The title poem is an elegant sestina in which “perseverance” is the end word of one line per stanza. The relationship with his father is a connecting thread in the book, culminating in the several tender poems that close the book. Here he remembers caring for his father, who had dementia, in the final two years of his life, and devotes a final pantoum to the childhood joy of reading aloud with him.

The title comes from the name of the pub where Antrobus’s father drank while his son waited outside. The title poem is an elegant sestina in which “perseverance” is the end word of one line per stanza. The relationship with his father is a connecting thread in the book, culminating in the several tender poems that close the book. Here he remembers caring for his father, who had dementia, in the final two years of his life, and devotes a final pantoum to the childhood joy of reading aloud with him.

A number of poems broaden the perspective beyond the personal to give a picture of early Deaf history. Several mention Alexander Graham Bell, whose wife and mother were both deaf, while in one the ghost of Laura Bridgeman (the subject of Kimberly Elkins’s excellent novel What Is Visible) warns Helen Keller about the unwanted fame that comes with being a poster child for disability. The poet advocates a complete erasure of Ted Hughes’s offensive “Deaf School” (sample lines: “Their faces were alert and simple / Like faces of little animals”; somewhat ironically, Antrobus went on to win the Ted Hughes Award last month!) and bases the multi-part “Samantha” on interviews with a Deaf Jamaican woman who moved to England in the 1980s. The text also includes a few sign language illustrations, including numbers that mark off section divisions.

The Perseverance is an issues book that doesn’t resort to polemic; a bereavement memoir that never turns overly sentimental; and a bold statement of identity that doesn’t ignore complexities. Its mixture of classical forms and free verse, the historical and the personal, makes it ideal for those relatively new to poetry, while those who enjoy the sorts of poets he quotes and tips the hat to (like Kei Miller, Danez Smith and Derek Walcott) will find a resonant postcolonial perspective.

A favorite passage from “Echo” (I’m a sucker for alliteration):

the ravelled knot of tongues,

of blaring birds, consonant crumbs

of dull doorbells, sounds swamped

in my misty hearing aid tubes.

The winner of the Rathbones Folio Prize will be announced on May 20th.

My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Apart from a few third-person segments about the parents, the chapters, set between 1997 and 2005, trade off first-person narration duties between Zora, a romantic would-be writer, and Sasha, the black sheep and substitute family storyteller-in-chief, who dates women and goes by Ashes when she starts wearing a binder. It’s interesting to discover examples of queer erasure in both parents’ past, connecting Beatrice more tightly to Sasha than it first appears – people always condemn most vehemently what they’re afraid of revealing in themselves.

Apart from a few third-person segments about the parents, the chapters, set between 1997 and 2005, trade off first-person narration duties between Zora, a romantic would-be writer, and Sasha, the black sheep and substitute family storyteller-in-chief, who dates women and goes by Ashes when she starts wearing a binder. It’s interesting to discover examples of queer erasure in both parents’ past, connecting Beatrice more tightly to Sasha than it first appears – people always condemn most vehemently what they’re afraid of revealing in themselves.

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation:

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation: The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement. What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.

What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort. Rewilding is a big buzz word in current nature and environmental writing. Few could be said to have played as major a role in the UK’s successful species reintroduction projects as Roy Dennis, who has been involved with the RSPB and other key organizations since the late 1950s. He trained as a warden at two of the country’s most famous bird observatories, Lundy Island and Fair Isle. Most of his later work was to focus on birds: white-tailed eagles, red kites, and ospreys. Some of these projects extended into continental Europe. He also writes about the special challenges posed by mammal reintroductions; beavers get a chapter of their own. Every initiative is described in exhaustive detail, full of names and dates, whereas I would have been okay with an overview. This feels like more of an insider’s history rather than a layman’s introduction. I have popped it on my husband’s bedside table in hopes that, with his degree in wildlife conservation, he’ll be more interested in the nitty-gritty.

Rewilding is a big buzz word in current nature and environmental writing. Few could be said to have played as major a role in the UK’s successful species reintroduction projects as Roy Dennis, who has been involved with the RSPB and other key organizations since the late 1950s. He trained as a warden at two of the country’s most famous bird observatories, Lundy Island and Fair Isle. Most of his later work was to focus on birds: white-tailed eagles, red kites, and ospreys. Some of these projects extended into continental Europe. He also writes about the special challenges posed by mammal reintroductions; beavers get a chapter of their own. Every initiative is described in exhaustive detail, full of names and dates, whereas I would have been okay with an overview. This feels like more of an insider’s history rather than a layman’s introduction. I have popped it on my husband’s bedside table in hopes that, with his degree in wildlife conservation, he’ll be more interested in the nitty-gritty. The title is the word for winter in the Northern Sámi language. Galloway, a journalist, traded in New York City for Arctic Norway after a) a DNA test told her that she had Sámi blood and b) she met and fell for Áilu, a reindeer herder, at a wedding. She enrolled in an intensive language learning course at university level and got used to some major cultural changes: animals were co-workers here rather than pets (like the two cats she brought with her); communal meals and drawn-out goodbyes were not the done thing; and shamans were still active (one helped them find a key she lost). Footwear neatly sums up the difference. The Prada heels she brought “just in case” ended up serving as hammers; instead, she helped Áilu’s mother make reindeer skins into boots. Two factors undermined my enjoyment: Alternating chapters about her unhappy upbringing in Indiana don’t add much of interest, and, after her relationship with Áilu ends, the book feels aimless. However, I appreciated her words about DNA not defining you, and family being what you make it.

The title is the word for winter in the Northern Sámi language. Galloway, a journalist, traded in New York City for Arctic Norway after a) a DNA test told her that she had Sámi blood and b) she met and fell for Áilu, a reindeer herder, at a wedding. She enrolled in an intensive language learning course at university level and got used to some major cultural changes: animals were co-workers here rather than pets (like the two cats she brought with her); communal meals and drawn-out goodbyes were not the done thing; and shamans were still active (one helped them find a key she lost). Footwear neatly sums up the difference. The Prada heels she brought “just in case” ended up serving as hammers; instead, she helped Áilu’s mother make reindeer skins into boots. Two factors undermined my enjoyment: Alternating chapters about her unhappy upbringing in Indiana don’t add much of interest, and, after her relationship with Áilu ends, the book feels aimless. However, I appreciated her words about DNA not defining you, and family being what you make it. Native American poet Sharmagne Leland St.-John’s fifth collection is a nostalgic and bittersweet look at people and places from one’s past. There are multiple elegies for public figures – everyone from Janis Joplin to Virginia Woolf – as well as for some who aren’t household names but have important stories that should be commemorated, like Hector Pieterson, a 12-year-old boy killed during the Soweto Uprising for protesting enforced teaching of Afrikaans in South Africa in 1976. Many of the elegies are presented as songs. Personal sources of sadness, such as a stillbirth, disagreements with a daughter, and ageing, weigh as heavily as tragic world events.

Native American poet Sharmagne Leland St.-John’s fifth collection is a nostalgic and bittersweet look at people and places from one’s past. There are multiple elegies for public figures – everyone from Janis Joplin to Virginia Woolf – as well as for some who aren’t household names but have important stories that should be commemorated, like Hector Pieterson, a 12-year-old boy killed during the Soweto Uprising for protesting enforced teaching of Afrikaans in South Africa in 1976. Many of the elegies are presented as songs. Personal sources of sadness, such as a stillbirth, disagreements with a daughter, and ageing, weigh as heavily as tragic world events. Coming in at under 260 pages, this isn’t your standard comprehensive biography. Sampson instead describes it as a “portrait,” one that takes up the structure of EBB’s nine-book epic poem, Aurora Leigh, and is concerned with themes of identity and the framing of stories. Elizabeth, as she is cosily called throughout the book, wrote poems that lend themselves to autobiographical interpretation – “her body of work creates a kind of looking glass in which, dimly, we make out the person who wrote it,” Sampson asserts.

Coming in at under 260 pages, this isn’t your standard comprehensive biography. Sampson instead describes it as a “portrait,” one that takes up the structure of EBB’s nine-book epic poem, Aurora Leigh, and is concerned with themes of identity and the framing of stories. Elizabeth, as she is cosily called throughout the book, wrote poems that lend themselves to autobiographical interpretation – “her body of work creates a kind of looking glass in which, dimly, we make out the person who wrote it,” Sampson asserts.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.)

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.) Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also  Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right.

Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right. The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be.

The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be. The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong.

The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong. Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.”

Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.” All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning.

All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning. Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife.

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife. My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”).

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”). On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)

On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)